Murder on the Orient Express (1974 film)

Murder on the Orient Express is a 1974 British mystery film directed by Sidney Lumet, produced by John Brabourne and Richard Goodwin, and based on the 1934 novel of the same name by Agatha Christie.

| Murder on the Orient Express | |

|---|---|

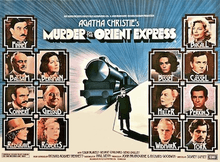

Original British quad format film poster | |

| Directed by | Sidney Lumet |

| Produced by | John Brabourne Richard Goodwin |

| Screenplay by | Paul Dehn |

| Based on | Murder on the Orient Express by Agatha Christie |

| Starring | Albert Finney Lauren Bacall Martin Balsam Ingrid Bergman Jacqueline Bisset Jean-Pierre Cassel Sean Connery John Gielgud Wendy Hiller Anthony Perkins Vanessa Redgrave Rachel Roberts Richard Widmark Michael York |

| Music by | Richard Rodney Bennett |

| Cinematography | Geoffrey Unsworth |

| Edited by | Anne V. Coates |

Production company | G.W. Films Limited |

| Distributed by | Anglo-EMI Film Distributors (UK) Paramount Pictures (USA) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 128 minutes[1] |

| Country | United Kingdom[2] |

| Language | English |

| Budget | ₤554,100 ($1.4 million)[3] |

| Box office | $35.7 million[4] |

The film features the Belgian detective Hercule Poirot (Albert Finney), who is asked to investigate the murder of an American business tycoon aboard the Orient Express train. The suspects are portrayed by an all-star cast, including Lauren Bacall, Ingrid Bergman, Sean Connery, John Gielgud, Vanessa Redgrave, Michael York, Jacqueline Bisset, Anthony Perkins and Wendy Hiller. The screenplay is by Paul Dehn.

The film was a commercial and critical success. It received six nominations at the 47th Academy Awards: Best Actor (Finney), Best Supporting Actress (Bergman), Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Original Score, Best Cinematography and Best Costume Design. Of these nominations, Bergman was the only winner.

Plot

In December 1935, Hercule Poirot is traveling aboard the Orient Express, encountering his friend Signor Bianchi, a director of the company which owns the line. The other passengers traveling in Poirot and Bianchi's coach are: American widow Harriet Hubbard; American businessman Samuel Ratchett, with his English manservant Edward Beddoes and secretary/translator Hector McQueen; elderly Russian Princess Natalia Dragomiroff and her German maid Hildegarde Schmidt; Hungarian diplomat Count Rudolf Andrenyi and his wife Elena; British Indian Army officer Colonel John Arbuthnot; Mary Debenham, a teacher; Greta Ohlsson, a Swedish missionary; Italian-American car salesman Antonio Foscarelli; and Cyrus Hardman, an American theatrical agent.

The morning after the train's departure from Istanbul, Ratchett tries to secure Poirot's services as a bodyguard for $15,000, as he has received death threats, but Poirot has no interest. That night, Bianchi lets Poirot use his compartment as he goes to sleep in another coach. During the journey, the train is stopped in heavy snows in Yugoslavia.

The next morning, Ratchett is found stabbed to death in his cabin. Bianchi entreats Poirot to solve the case. They enlist the help of Stavros Constantine, a Greek medical doctor who was travelling in the other coach.

Dr. Constantine finds Ratchett was stabbed 12 times, though some wounds were slight. Poirot's reconstructed timeline of passenger activities the night before indicate that Ratchett was murdered at about 1:15 a.m. The doors to the other cars were locked, so the murderer is likely one of the passengers in Poirot's coach, or its French conductor, Pierre Michel.

Found at the crime scene is a fragment of a burned letter. Examining the letter, Poirot discovers that Ratchett was actually Lanfranco Cassetti, a gangster who five years earlier planned the kidnapping and murder of Daisy Armstrong, infant daughter of British Army Colonel Hamish Armstrong and his American wife Sonia. Overcome with grief, the pregnant Mrs. Armstrong went into premature labour and died giving birth to a stillborn baby. A French maidservant named Paulette, suspected of complicity in the kidnapping, committed suicide, only to be found innocent later. Colonel Armstrong, consumed by these tragedies, committed suicide. Cassetti betrayed his partner by fleeing the country with the ransom, and was only revealed to be involved on the eve of his partner's execution.

Several clues are quickly discovered suggesting that an assassin boarded the train during the night while it was stuck in the snowdrift, murdered Cassetti and then left the train. Mrs. Hubbard reports that she detected the presence of a man in her bed. Then, a button from a sleeping car conductor's uniform is discovered. Pierre confirms that he is not missing any buttons from his uniform. Later, an entire conductor's uniform is discovered that does not fit Pierre and is missing a button. In the uniform's pocket is a conductor's pass key. Finally, Mrs. Hubbard discovers a bloody dagger. Dr. Constantine confirms that it could have inflicted all the wounds found on Cassetti's body. Poirot later agrees with Foscarelli that the assassin was likely a member of a rival Mafia gang, exacting vengeance as part of a Mafia feud.

As these clues are being discovered, Poirot begins interviewing the passengers. He learns that: McQueen was the son of the District Attorney who prosecuted the case and was very fond of Mrs. Armstrong; Beddoes had been a British Army batman; Countess Andrenyi is of German descent and her maiden name is Grunwald; Greta Ohlsson has a limited knowledge of the English language and has been to America; Pierre Michel's daughter died five years earlier of scarlet fever; Col. Arbuthnot, who displays a knowledge of Armstrong's military decorations, plans to wed Mary Debenham. When Poirot interviews Princess Dragomiroff he discovers she is a great friend of Linda Arden, Mrs. Armstrong's mother; the Princess was Sonia's godmother. He learns that the Armstrongs had a butler, a secretary, a cook, a chauffeur and a nursemaid to Daisy. Poirot flatters Hildegarde Schmidt by saying he knows a good cook when he sees one, and she responds to his request for a photo of the maid Paulette, with whom Miss Schmidt was friendly. Foscarelli vehemently denies ever having been in private service as a chauffeur. Hardman reveals he is, in fact, a Pinkerton detective hired to guard Cassetti. When shown the photo of Paulette, Hardman breaks down and reveals he knew her.

Poirot gathers the suspects together, stating he has formulated two possible scenarios. The first, his simple solution, is the one suggesting that Cassetti's murder was the result of a Mafia feud. The second, his complex solution, links all the suspects on the coach to the Armstrong case. In addition to the earlier self-incriminating revelations by Hardman, McQueen, Miss Schmidt and the Princess, the Princess had incriminated three others: when asked Mrs Armstrong's maiden name, she replied "Greenwood", the English for "Grunwald", allowing Poirot to deduce that Countess Elena was Mrs Armstrong's sister, and Count Andrenyi her brother-in-law; the Princess also claimed the secretary's name was "Miss Freebody", so Poirot deduced the secretary was in fact Mary Debenham (as in the London department store Debenham and Freebody). Poirot then presents the motives of the other suspects: Pierre was Paulette's father; Beddoes was Colonel Armstrong's army batman and the family butler; Miss Ohlsson was Daisy's nursemaid (having inadvertently shown an understanding of complex English words); Col. Arbuthnot was a close army friend of Armstrong's; Foscarelli was the Armstrongs' private chauffeur; Hardman was a police officer in love with Paulette and Mrs Hubbard is Linda Arden, Mrs Armstrong's mother. McQueen had drugged Cassetti so each of the passengers could stab him – with the Andrenyis stabbing Cassetti together, totaling 12 stab wounds. The noises which disturbed Poirot's sleep were contrived to obfuscate the time of death.

Poirot asks Bianchi to choose one of the two solutions to present to the police once the train is freed from the snowdrift. He admits that the Yugoslavian police will likely prefer the simple solution. Bianchi decides that Cassetti deserved to die, and elects the simple solution. Poirot agrees, admitting he will struggle with his conscience when he gives his report to the police. The passengers celebrate with champagne as the train is freed of the snow and resumes its journey.

Cast

- Albert Finney as Hercule Poirot

- Lauren Bacall as Mrs. Hubbard

- Martin Balsam as Bianchi

- Ingrid Bergman as Greta Ohlsson

- Jacqueline Bisset as Countess Helena Andrenyi

- Jean-Pierre Cassel as Pierre Paul Michel

- Sean Connery as Colonel Arbuthnot

- John Gielgud as Edward Beddoes

- Wendy Hiller as Princess Natalia Dragomiroff

- Anthony Perkins as Hector McQueen

- Vanessa Redgrave as Mary Debenham

- Rachel Roberts as Hildegarde Schmidt

- Richard Widmark as Ratchett

- Michael York as Count Rudolf Andrenyi

- Colin Blakely as Cyrus B. Hardman

- George Coulouris as Dr. Constantine

- Denis Quilley as Antonio Foscarelli

- Vernon Dobtcheff as Concierge

- Jeremy Lloyd as A.D.C.

- John Moffatt as Chief Attendant

Production

Development

Agatha Christie had been quite displeased with some film adaptations of her works made in the 1960s, and accordingly was unwilling to sell any more film rights. When Nat Cohen, chairman of EMI Films, and producer John Brabourne attempted to get her approval for this film, they felt it necessary to have Lord Mountbatten of Burma (of the British royal family and also Brabourne's father-in-law) help them broach the subject. In the end, according to Christie's husband Max Mallowan, "Agatha herself has always been allergic to the adaptation of her books by the cinema, but was persuaded to give a rather grudging appreciation to this one."

According to one report, Christie gave approval because she liked the previous films of the producers, Romeo and Juliet and Tales of Beatrix Potter.[5]

Casting

Christie's biographer Gwen Robyns quoted her as saying, "It was well made except for one mistake. It was Albert Finney, as my detective Hercule Poirot. I wrote that he had the finest moustache in England—and he didn't in the film. I thought that a pity—why shouldn't he?"[6]

Cast members eagerly accepted upon first being approached. Lumet went to Sean Connery first, saying that if you get the biggest star, the rest will come along. Bergman was initially offered the role of Princess Dragomiroff, but instead requested to play Greta Ohlsson. Lumet said:

She had chosen a very small part, and I couldn't persuade her to change her mind. She was sweetly stubborn. But stubborn she was ... Since her part was so small, I decided to film her one big scene, where she talks for almost five minutes, straight, all in one long take. A lot of actresses would have hesitated over that. She loved the idea and made the most of it. She ran the gamut of emotions. I've never seen anything like it.[7]:246–247

The entire budget was provided by EMI. The cost of the cast came to ₤554,100.[3]

Filming

Unsworth shot the film in Panavision. Interiors were filmed at Elstree Studios. Exterior shooting was mostly done in France in 1973, with a railroad workshop near Paris standing in for Istanbul station. The scenes of the train proceeding through central Europe were filmed in the Jura Mountains on the then-recently closed railway line from Pontarlier to Gilley, with the scenes of the train stuck in snow being filmed in a cutting near Montbenoît.[8] There were concerns about a lack of snow in the weeks preceding the scheduled shooting of the snowbound train, and plans were made to truck in large quantities of snow at considerable expense. However, heavy snowfall the night before the shooting made the extra snow unnecessary—just as well, as the snow-laden backup trucks had themselves become stuck in the snow.[9]

Music

Richard Rodney Bennett's Orient Express theme has been reworked into an orchestral suite and performed and recorded several times. It was performed on the original soundtrack album by the Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden under Marcus Dods. The piano soloist was the composer himself.

Reception

Box office

Murder on the Orient Express was released theatrically in the UK on 24 November 1974. The film was a success at the box office, given its tight budget of $1.4 million,[10] earning $36 million in North America,[10][11] making it the 11th highest-grossing film of 1974. Nat Cohen claimed it was the first film completely financed by a British company to make the top of the weekly US box office charts in Variety.[12]

Critical response

The film received positive reviews upon release and currently holds an 89% "Fresh" rating on the website Rotten Tomatoes from 35 reviews with an average rating of 7.74/10.[13] Roger Ebert gave the film three out of four stars, writing that the film "provides a good time, high style, a loving salute to an earlier period of filmmaking".[14] The New York Times's chief critic of the era, Vincent Canby, wrote:

[...] had Dame Agatha Christie's Murder on the Orient Express been made into a movie 40 years ago (when it was published here as Murder on the Calais Coach), it would have been photographed in black-and-white on a back lot in Burbank or Culver City, with one or two stars and a dozen character actors and studio contract players. Its running time would have been around 67 minutes and it could have been a very respectable B-picture. Murder on the Orient Express wasn't made into a movie 40 years ago, and after you see the Sidney Lumet production that opened yesterday at the Coronet, you may be both surprised and glad it wasn't. An earlier adaptation could have interfered with plans to produce this terrifically entertaining super-valentine to a kind of whodunit that may well be one of the last fixed points in our inflationary universe.[15]

Agatha Christie

Christie later said that this and Witness for the Prosecution were the only adaptations of her books that she liked.[5]

Awards and nominations

See also

- Murder on the Orient Express (2017 film), directed by and starring Kenneth Branagh

References

- AFI Murder on the Orient Express Retrieved 2020-04-27

- http://lumiere.obs.coe.int/web/film_info/?id=61364

- Can film-makers Carry On? Bell, Brian. The Observer 11 August 1974: 11.

- Boost for studios The Guardian 9 July 1975: 5.

- Mills, Nancy. The case of the vanishing mystery writer: Christie liked only two of the 19 movies made from her books. Chicago Tribune 30 October 1977: h44.

- Sanders, Dennis and Len Lovallo. The Agatha Christie Companion: The Complete Guide to Agatha Christie's Life and Work, (1984), pgs. 438–441. Subscription required ISBN 978-0425118450

- Chandler, Charlotte (20 February 2007). Ingrid: Ingrid Bergman, A Personal Biography. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 19, 21, 294. ISBN 978-1416539148.

- Trains Oubliés Vol.2: Le PLM by José Banaudo, p. 54 (French). Editions du Cabri, Menton, France

- DVD documentary "Making Murder on the Orient Express: The Ride"

- Alexander Walker, National Heroes: British Cinema in the Seventies and Eighties, Harrap, 1985 p. 130

- "Murder on the Orient Express, Box Office Information". The Numbers. Retrieved 5 January 2012.

- "Murder on the Orient Express' tops US charts". The Times. London. 11 February 1975. p. 7.

- Movie Reviews for Murder on the Orient Express. Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- Roger Ebert reviews Murder on the Orient Express. Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 23 September 2012.

- Canby, Vincent (25 November 1974). "Crack 'Orient Express' Clicks as Film". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Murder on the Orient Express (1974 film) |