Shilajit

Shilajit (Sanskrit: शिलाजीत, مامي in Farsi or Dari, śilājatu, سلاجیت in Urdu)[1] or mumijo is a blackish-brown powder or an exudate from high mountain rocks, often found in the Himalayas, Nepal, Girda(Buldhana)MH., Russia, Mongolia and in the north of Chile, where it is called Andean Shilajit.[2] It is a natural substance formed for centuries by the gradual decomposition of plants by the action of microorganisms. While shilajit has been used in traditional Indian medicine as an antiaging compound, its health benefits lack substantial scientific evidence.[3]

Etymology

The English word Shilajeet is a phonetic adaptation of "śilājīt" (Hindi: शिलाजीत), which in turn goes back to Sanskrit (Sanskrit: शिलाजतु, śilājatu).[1] The literal meaning of the Sanskrit compound is "mountain tar", the first element शिला (śilā) meaning "pertaining to, or having the properties of a rock, mountain", the second जातु (jatu) denoting "gum, lac; any tarry substance"[4]

Terminology

Shilajeet comes from the Sanskrit compound word shilajatu meaning "rock-tar", which is the regular Ayurveda term. It is also spelled shilajeet (Hindi: शिलाजीत) and salajeet (Urdu: سلاجیت).

Shilajeet is known universally by various other names,[5] such as mineral pitch or mineral wax in English, black asphaltum, Asphaltum punjabianum in Latin, also locally as shargai, dorobi, barahshin, baragshun (Mongolian: Барагшун), mummenayyee (Farsi مومنایی), tasmayi (Kazakh: тасмайы, lit. rock oil),[6] brag zhun (Tibetan: བྲག་ཞུན་), chao-tong, wu ling zhi (Chinese: 五灵脂, which generally refers to the excrement of flying squirrels), badha-naghay (Burushaski for "feces of a featherless flying squirrel), baad-a-ghee (Wakhi for "devil's feces"), and arkhar-tash (Kyrgyz: архар-таш).[5] The most widely used name in the former Soviet Union is mumiyo (Russian: мумиё, variably transliterated as mumijo, mumio, momia, and moomiyo), which is ultimately from Latin (mumia) body-preserving, a borrowing of the medieval Arabic mūmiya (مومياء) and from a Persian mūm (موم) or mūmiya (مومیا).

Origin

Several researchers have noted that Shilajeet is unlike mineral tar seeps and is most likely of vegetable origin. A succulent plant Euphorbia royleana has been observed growing near collection sites and is suggested as a likely origin as its gum has a similar composition.[7]

One more recent hypothesis states that the species of Asterella, Dumortiera, Marchantia, Pellia, Plagiochasma and Stephenrencella-Anthoceros have been growing in shilajeet neighborhood and it is these plants, mosses and liverworts that during centuries have been fueling the Shilajeet deposits generation

Mythology

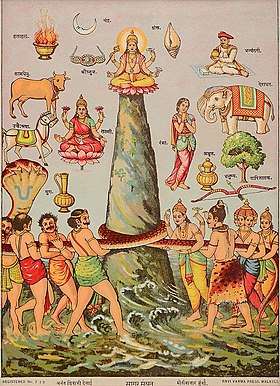

According to ancient Hindu philosophy, shilajatu was created from a friction of the celestial spheres during samudra manthana. The Devas and the Asuras agreed to churn the primal ocean in order to obtain the beneficial amrita, the nectar of immortality. They wrapped the king snake Vasuki Naga around Mount Mandara, which was used as a churning rod, and mixed the primordial milk ocean. The churning process was laborious,[8] and the sweat of the gods and demons interacted with the amrita, creating shilajeet deposits around the mountains of the world.

History

The first documented reference to Shilajeet in the form of "Shilajatu" dates back to the sixth century BCE. Sushruta Samhita, a third century CE Sanskrit medical treatise states: "A gelatinous substance that is secreted from the [9] side of the mountains when they have become heated by the rays of the sun in the months of Jyaishta and Ashadha. This substance is what is known as Šilájatu and it cures all distempers of the body.[10] During medieval era, Shilajeet had been considered one of the rasa (nutritive fluid) to endow a person with magical power when taken with particular metals, bhasmas, herbs, ghee or honey. A famous alchemical Siddhanjana also known as the "ointment of Mags" included camphor, shilajatu, some psychoactive herbs, as well as metal oxides and minerals. It allegedly enabled the practitioner to see "all the seven worlds of Hell (Patala)".[11] Shilajeet is found predominantly in Himalaya, Tibet mountains, Altai and Caucasus mountains. The color range varies from a yellowish brown to pitch-black, depending on composition. For use in Ayurvedic medicine the black variant is considered the most potent. Shilajeet has been described as 'mineral oil', 'stone oil', 'Mountain Blood' or 'rock sweat', as it seeps from cracks in mountains due mostly to the warmth of the sun. There are many local legends and stories about its origin, use and properties, often wildly exaggerated. It should not be confused with ozokerite, also a humic substance, similar in appearance, but apparently without medicinal qualities.

Once cleaned of impurities and extracted, Shilajeet is a homogeneous brown-black paste-like substance, with a glossy surface, a peculiar smell and bitter taste. Dry Shilajeet density ranges from 1.1 to 1.8 g/cm3. It has a plastic-like behavior, at a temperature lower than 20 °C (68 °F) it will solidify and will soften when warmed. It easily dissolves in water without leaving any residue, and it will soften when worked between the fingers.

It is still unclear whether Shilajeet has a geological or biological origin as it has numerous traces of vitamins and amino acids. A Shilajeet-like substance from Antarctica was found to contain glycerol derivatives and was also believed to have medicinal properties.[12]

Physical and chemical properties

Shilajit or Mumijo look like a dark brown (almost black) resinous mass. Depending on where the Shilajit is collected from, it may look slightly lighter or darker in color, as well as being tinged with shades of amber or red. Shilajit is very similar to other humic substances found in the soil as it is about 60-80% humus - however, after millions of years and under precise conditions as found at high altitudes, these substances undergo a profound change.

Shilajit has a melting point of 80 °C/176 °F. If placed in a fridge or kept at low temperatures, Shilajit resin begins to harden and becomes brittle.

Mumijo has an exceptionally high affinity for water and is able to dissolve readily in water, whether at room temperature or heated. Shilajit does not dissolve into oil as it does in water, however it does naturally contain a small portion of fatty acid components. In resin or powder form, one can easily mix it into an ointment.

The list of elements in Shilajit[13] remains more or less the same across all types, with slight differences in the ratios of each depending on the geographical origin.

Health benefits

The proposed immuno-modulatory activity does not stand the test of critical assessment and are considered as unproven.[3]

Shilajeet has been the subject of scientific research in Russia and India since the early 1950s. In the former USSR, medical preparations based on mumiyo/shilajeet are currently sold in Russia as a daily recuperative health tonic.[14]

The health benefits of Shilajit have been reported to differ from region to region, depending on the place from which it was extracted.[15][16]

References

- Rigpa Wiki

- Cornejo, Alberto; Jiménez, José M.; Caballero, Leonardo; Melo, Francisco; Maccioni, Ricardo B. (2011). "Fulvic acid inhibits aggregation and promotes disassembly of tau fibrils associated with Alzheimer's disease". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 27 (1): 143–153. doi:10.3233/JAD-2011-110623. ISSN 1875-8908. PMID 21785188.

- Wilson, Eugene; Rajamanickam, G. Victor; Dubey, G. Prasad; Klose, Petra; Musial, Frauke; Saha, F. Joyonto; Rampp, Thomas; Michalsen, Andreas; Dobos, Gustav J. (June 2011). "Review on shilajit used in traditional Indian medicine". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 136 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2011.04.033. PMID 21530631.

- Chicago, The University of; (CRL), Center for Research Libraries. "Digital South Asia Library". dsalsrv02.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2017-12-23.

- Winston, David; Maimes, Steven (2007). "Shilajit". Adaptogens: Herbs for Strength, Stamina, and Stress Relief. Inner Traditions / Bear & Company. pp. 201–204. ISBN 978-1-59477-969-5. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- Kizaibek, Murat (2013). "Research advances of Tasmayi". Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 38 (3): 443–448. doi:10.4268/cjcmm20130331.

- Lal, VK; Panday, KK; Kapoor, ML (1988). "Literary support to the vegetable origin of shilajit". Ancient Science of Life. 7 (3–4): 145–8. PMC 3336633. PMID 22557605.

- Krishnaswamy, N. "The Bagavata Purana for the First Time Reader" (PDF). pp. 71–72.

- "Bhagavata Purana" (PDF).

- Suśruta; Kunjalal Bhishagratna (1998). Suśruta Saṁhitā: Nidānasthāna-cikitsā sthāna. Chowkhamba Sanskrit Series Office. ISBN 978-81-7080-011-8.

- Rigveda Samhita Siddhanjana Part 1 Kapali Sastry T. V. at the Internet Archive

- Anna Aiello, Ernesto Fattorusso, Marialuisa Menna, Rocco Vitalone, Heinz C. Schröder, Werner E. G. Müller (September 2010). "Mumijo Traditional Medicine: Fossil Deposits from Antarctica (Chemical Composition and Beneficial Bioactivity)". Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2011: 738131. doi:10.1093/ecam/nen072. PMC 3139983. PMID 18996940.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Matyukhin, Valentin; Ironclad, Polly (2017-08-01). "Shilajit Benefits, Myths and List of Organic Elements". Pure Himalayan Shilajit. Open Publishing. Retrieved 2019-07-28.

- Schepetkin, Igor; Khlebnikov, Andrei; Kwon, Byoung Se (2002). "Medical drugs from humus matter: Focus on mumie". Drug Development Research. 57 (3): 140–159. doi:10.1002/ddr.10058.

- "Google Scholar". scholar.google.com. Retrieved 2019-12-01.

- Agarwal, Suraj P.; Khanna, Rajesh; Karmarkar, Ritesh; Anwer, Md Khalid; Khar, Roop K. (May 2007). "Shilajit: a review". Phytotherapy Research. 21 (5): 401–405. doi:10.1002/ptr.2100. ISSN 0951-418X. PMID 17295385.

Further reading

- Bucci, Luke R (2000). "Selected herbals and human exercise performance". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 72 (2 Suppl): 624S–36S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/72.2.624S. PMID 10919969.

- Hill, Carol A.; Forti, Paolo (1997). Cave minerals of the world. 2 (2nd ed.). National Speleological Society. p. 223. ISBN 978-1-879961-07-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schepetkin, Igor; Khlebnikov, Andrei; Kwon, Byoung Se (2002). "Medical drugs from humus matter: Focus on mumie". Drug Development Research. 57 (3): 140–159. doi:10.1002/ddr.10058.

- Frolova, L. N.; Kiseleva, T. L. (1996). "Chemical composition of mumijo and methods for determining its authenticity and quality (a review)". Pharmaceutical Chemistry Journal. 30 (8): 543–547. doi:10.1007/BF02334644.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kiseleva, T. L.; Frolova, L. N.; Baratova, L. A.; Yus'Kovich, A. K. (1996). "HPLC study of fatty-acid components of dry mumijo extract". Pharmaceutical Chemistry Journal. 30 (6): 421–423. doi:10.1007/BF02219332.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Frolova, L. N.; Kiseleva, T. L.; Kolkhir, V. K.; Baginskaya, A. I.; Trumpe, T. E. (1998). "Antitoxic properties of standard dry mumijo extract". Pharmaceutical Chemistry Journal. 32 (4): 197–199. doi:10.1007/BF02464208.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kiseleva, T. L.; Frolova, L. N.; Baratova, L. A.; Baibakova, G. V.; Ksenofontov, A. L. (1998). "Study of the amino acid fraction of dry mumijo extract". Pharmaceutical Chemistry Journal. 32 (2): 103–108. doi:10.1007/BF02464176.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kiseleva, T. L.; Frolova, L. N.; Baratova, L. A.; Ivanova, O. Yu.; Domnina, L. V.; Fetisova, E. K.; Pletyushkina, O. Yu. (1996). "Effect of mumijo on the morphology and directional migration of fibroblastoid and epithelial cellsin vitro". Pharmaceutical Chemistry Journal. 30 (5): 337–338. doi:10.1007/BF02333977.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Joshi, G. C., K. C. Tiwari, N. K. Pande and G. Pande. 1994. Bryophytes, the source of the origin of Shilajeet – a new hypothesis. B.M.E.B.R. 15(1–4): 106–111.

- Ghosal, S., B. Mukherjee and S. K. Bhattacharya. 1995. Ind. Journal of Indg. Med. 17(1): 1–11.

- Ghosal, S.; Reddy, J. P.; Lal, V. K. (1976). "Shilajit I: Chemical constituents". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 65 (5): 772–3. doi:10.1002/jps.2600650545. PMID 932958.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Faruqi, S.H. 1997, Nature and Origin of Salajit, Hamdard Medicus, Vol XL, April–June, pages 21–30

- Zahler, P; Karin, A (1998). "Origin of the floristic components of Salajit". Hamdard Medicus. 41 (2): 6–8.

- Shafiq, Muhammad Imtiaz; Nagra, Saeed Ahmad; Batool, Nayab (2006). "Biochemical and Trace Mineral Analysis of Silajit Samples From Pakistan". Nutritional Sciences. 9 (3): 190–4.