Moor frog

The moor frog (Rana arvalis) is a slim, reddish-brown, semiaquatic amphibian native to Europe and Asia. It is a member of the family Ranidae, or true frogs.

| Moor frog | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Anura |

| Family: | Ranidae |

| Genus: | Rana |

| Species: | R. arvalis |

| Binomial name | |

| Rana arvalis Nilsson, 1842 | |

| |

Taxonomy

The family the moor frog belongs to, Ranidae, is a broad group containing 605 species. The family is like a “catch-all” for ranoid frogs that do not belong to any other families.[2] Since this is the case, the characteristics that define them are more general, and the frogs are found all throughout the world, on every continent but Antarctica.

The moor frog's genus, Rana, is a little more specific. Frogs of this genus are found in Europe, Asia, South America, and North America. The moor frog is not found in either of the Americas, unlike the foothill yellow-legged frog, Cascades frog, and Columbia spotted frog, which are all found in North America.

The moor frog's scientific name, Rana arvalis means "frog of the fields".[3] It is also called the Altai brown frog because frogs from the Altai Mountains in Asia have been included in the R. arvalis species. The Altai frogs have some different characteristics such as shorter shins, but currently there is no official distinction and all frogs are placed under Rana arvalis.[1] The taxonomy may be more defined in the future.

Description

This is a small frog, characterized by an unspotted belly, a large, dark ear spot, and — often, not always — a pale stripe down the center of the back. They are generally described as a reddish-brown, but can also be yellow, gray, or light olive. Their bellies are white or yellow and they have a "bandit-like" black stripe going from their nose to their ears. They vary from 5.5 to 6.0 cm long, but can reach up to 7.0 cm in length, and their heads are more tapered than those of the Common frog (Rana temporaria). The skin on their flanks and thighs is smooth, and the posterior part of their tongues is forked and free. They have horizontal pupils, their feet are partially webbed, and their back legs are shorter than those of other species of frogs. The males are different from the females because of the nuptial pads on their first fingers and their paired guttural vocal sacs.[3]

Distribution and habitat

The species has an extensive distribution across Europe. It can be found inhabiting an area stretching from the lowlands of Central and Southern Europe to Siberia, in Austria, Belarus, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Romania, Russian Federation, Slovakia, Slovenia, Sweden, Switzerland, and Ukraine. However, they are believed to be extirpated in Switzerland and possibly in Siberia as well; the records of frogs being in Siberia at all may have been in error.[1] Alsace, France, constitutes the western boundary of their territory. Moor frogs were also confirmed to have been present in East Anglia in the UK, after archaeological remains were found.[4]

The types of land they can inhabit are greatly varied. They live in tundra, forest tundra, forest, forest steppe, and steppe, forest edges and glades, semideserts, swamps, meadows, fields, bush lands, and gardens. They prefer areas untouched by humans, such as damp meadows and bogs, but they still may be able to live in agricultural and urban areas.[1]

Moor frogs provide a good model for studying local adaptation as they experience a wide range of environments and are relatively limited in their movements.[5][6] Their restriction in movements implies limited gene flow and facilitates evolution through adaptive genetic differentiation among populations.[7]

Ecology

Hibernation

Moor frogs will hibernate sometime between September and June, depending on the latitude of the location. Frogs in southwestern, plains areas will disappear later (around November or December) and return earlier (February). Frogs in cold, polar areas, though, will disappear sooner (in September) and return later (in June).[8]

Breeding

The mating season takes place between March and June right after the end of hibernation. Males form breeding choruses, and their songs sound similar to those of the agile frog, (Rana dalmatina). Their calls can "sound like air escaping from a submerged empty bottle: 'waug...waug...waug'. Males can also develop bright-blue coloration for a few days during the season.[9]

The spawning happens very quickly and is completed in three to 28 days. The spawn of each frog is laid in one or two clusters of 500-3000 eggs in warm, shallow waters like in ponds.

Metamorphosis

Metamorphosis happens between June and October. Larvae are about 45 mm long and colored dark with small metallic dots. When they become tadpoles, they eat algae and small invertebrates. The adult frogs' feeding is halted during the breeding season, but their diets consist of insects and various invertebrates.

Effects of acidification on population

Environmental plasticity

Increased acidity levels in breeding areas may be problematic for moor frog populations, as it reduces survival and growth of the aquatic embryos and larvae.[10][11][12][13][14] When exposed to acidity, moor frogs were however shown to be able to adapt relatively rapidly (within 16–40 generations). Local adaptation to acidity is also possible in survival during the embryonic stage, during which frogs are most sensitive to severe acidity.[15] Moreover, compared to those from neutral sites, acid origin populations have higher embryonic and larval acid tolerance (survival and larval period were less negatively affected by low pH), higher larval growth but slower larval development rates, and larger metamorphosing size. Divergence in embryonic acid tolerance and metamorphic size correlates most strongly with breeding pond pH, whereas divergence in larval period and larval growth correlates most strongly with latitude and predator density, respectively.[16]

Maternal effects

For female moor frogs, in order to optimize their maternal investments, they need to balance between their own fitness and the fitness of their offspring.[17][18] Additionally, under the great pressure exerted by acidification, female moor frogs also need to do a trade-off between quality and quantity of the offspring.[19]

Environmental stress, like acidity, may either select for or select against certain phenotypes and hence may increase variation in fitness. The adaptive optima for the population would shift greatly compared to those living in less acidic and more benign environments, thereby making the allocation of resources even more important. As a result of the increasing variation in fitness, frogs from acidic environments may also favor different reproductive strategies than those more benign environments.[20] Compared to neutral origin females, acid origin females tend to invest relatively more in fecundity than in egg size, invest more in their offspring than in self-maintenance, and increase their reproductive effort as their residual reproductive value decreases.[19] Consequently, acid origin females increase the clutch size and total reproductive output with age, while neutral origin females only increase egg size but not clutch size or total reproductive output with age.[19]

In conclusion, environmental acidification lowers maternal investment, selects for investment in larger eggs at a cost to fecundity, imposes negative effects on reproductive output, and alters the relationship between female phenotype and maternal investment, as well as strengthens the egg-size-fecundity trade-off.[19]

Population threats

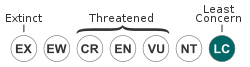

This species is generally common and often abundant. It faces few major threats and is currently classified as Least Concern by the IUCN. The moor frog may be impacted by the destruction and pollution of breeding sites and adjacent habitats, mostly through urbanization, recreational use of waterside areas, and intensive agriculture. The species does not appear to be notably susceptible to chytridiomycosis, although the fungus has been detected in frogs in Germany.[1]

References

- Kuzmin, S.; Tarkhnishvili, D.; Ishchenko, V.; et al. (2009). "Rana arvalis (errata version published in 2016)". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2009: e.T58548A86232114. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2009.RLTS.T58548A11800564.en.{{cite iucn}}: error: |doi= / |page= mismatch (help)

- Niles Eldredge, ed. (2002). Life on Earth: An Encyclopedia of Biodiversity, Ecology, and Evolution. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO.

- "Moor Frog (Rana arvalis)". World Association of Zoos and Aquariums. 2007.

- Snell, Charles (2006-02-01). "Status of the common tree frog in Britain". British Wildlife. 17: 153–160.

- Ward, R. D.; Skibinski, D. O.; Woodwark, M. (1992). "Protein heterozygosity, protein structure, and taxonomic differentiation". In K. M. Hecht (ed.). Evolutionary biology. New York: Plenum press. pp. 73–159.

- Beebee, T. J. C. (1996). Ecology and conservation of amphibians. London: Chapman and Hall.

- Hendry, A. P.; Kinnison, M. T.; Day, T.; Taylor, E. B. (2001). "Population mixing and the adaptive divergence of quantitative traits in discrete populations: a theoretical framework for empirical tests". Evolution. 55 (3): 459–466. doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2001.tb00780.x.

- Kuzmin, Sergius L. (1999). "Rana arvalis". AmphibiaWeb. Retrieved 26 March 2009.

- Otto Berninghausen; Friedo Berninghausen. "Moor frog - Rana arvalis".

- Freda, J. (1986). "The influence of acidic pond water on amphibians: a review". Water, Air, & Soil Pollution. 30 (1–2): 439–450. Bibcode:1986WASP...30..439F. doi:10.1007/bf00305213.

- Freda, J.; Sadinski, W. J.; Dunson, W. A. (1991). "Long term monitoring of amphibian populations with respect to the effects of acidic deposition". Water, Air, & Soil Pollution. 55 (3–4): 445–462. Bibcode:1991WASP...55..445F. doi:10.1007/bf00211205.

- Pierce, B. A. (1985). "Acid tolerance in amphibians". BioScience. 35 (4): 239–243. doi:10.2307/1310132. JSTOR 1310132.

- Pierce, B. A. (1993). "Effects of acid precipitation on amphibians". Ecotoxicology. 2 (1): 65–77. doi:10.1007/bf00058215. PMID 24203120.

- Böhmer, J.; Rahmann, H. (1990). "Influence of surface water acidification on amphibians". In W. Hanke (ed.). Biology and physiology of Amphibians. Stuttgart: Gustav Fischer Verlag.

- Räsänen, K.; Laurila, A.; Merilä, J. (2003). "Geographic variation in acid stress tolerance of the moor frog Rana arvalis. I. Local adaptation". Evolution. 57 (2): 352–362. doi:10.1554/0014-3820(2003)057[0352:gviast]2.0.co;2.

- Hangartner, S; Laurila, A; Räsänen, K (2012a). "Adaptive divergence in moor frog (Rana Arvalis) populations along an acidification gradient: inferences from Qst-Fst correlations". Evolution. 66 (3): 867–881. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01472.x. PMID 22380445.

- Roff, D. A. 1992. "The evolution of life histories. Local adaptation and genetics of acid-stress" Hall, New York, New York, USA.

- Sinervo, B (1999). "Mechanistic analysis of natural selection and a refinement of Lack's and Williams's principles". American Naturalist. 154: S26–S42. doi:10.2307/2463885. JSTOR 2463885.

- Räsänen, K.; Söderman, F.; Laurila, A.; Merilä, J. (2008). "Geographic variation in maternal investment: acidity affects egg size and fecundity in Rana arvalis". Ecology. 89 (9): 2553–2562. doi:10.1890/07-0168.1. PMID 18831176.

- Kisdi, E., G. Meszna, and L. Pasztor. 19 1998. "Individual optimization: mechanisms shaping the optimal reaction norm". Evolutionary Ecology 12:211-221.

- Some parts of this article were translated from the article Grenouille des champs on the French language Wikipedia.