Monument to the Battle of the Nations

The Monument to the Battle of the Nations (German: Völkerschlachtdenkmal, sometimes shortened to Völki[1]) is a monument in Leipzig, Germany, to the 1813 Battle of Leipzig, also known as the Battle of the Nations. Paid for mostly by donations and the city of Leipzig, it was completed in 1913 for the 100th anniversary of the battle at a cost of six million goldmarks.

| Völkerschlachtdenkmal | |

The monument from above, looking North-East | |

| Coordinates | 51°18′44″N 12°24′47″E |

|---|---|

| Location | Leipzig, Saxony, Germany |

| Designer | Bruno Schmitz |

| Material | Granite-faced concrete |

| Length | 80 metres (260 ft) |

| Width | 70 metres (230 ft) |

| Height | 91 metres (299 ft) |

| Beginning date | 18 October 1898 |

| Opening date | 18 October 1913 |

| Dedicated to | Battle of Leipzig |

The monument commemorates the defeat of Napoleon's French army at Leipzig, a crucial step towards the end of hostilities in the War of the Sixth Coalition. The coalition armies of Russia, Prussia, Austria and Sweden were led by Tsar Alexander I of Russia and Karl Philipp, Prince of Schwarzenberg. There were Germans fighting on both sides, as Napoleon's troops also included conscripted Germans from the left bank of the Rhine annexed by France, as well as troops from his German allies of the Confederation of the Rhine.

The structure is 91 metres (299 ft) tall. It contains over 500 steps to a viewing platform at the top, from which there are views across the city and environs. The structure makes extensive use of concrete, and the facings are of granite. It is widely regarded as one of the best examples of Wilhelmine architecture. The monument is said to stand on the spot of some of the bloodiest fighting, from where Napoleon ordered the retreat of his army.[2] It was also the scene of fighting in World War II, when Nazi forces in Leipzig made their last stand against U.S. troops.

History

Background

The War of the Sixth Coalition and the Battle of Leipzig

Following the French Revolution, France had waged a number of wars against its European neighbours. Napoleon Bonaparte had taken control of the country, first as Consul from 1799, and reigned as Emperor of the French under the title Napoleon I since 1804. Over the course of the hostilities, the Holy Roman Empire had ceased to exist following the abdication of Emperor Francis II, bowing to Napoleon's pressure, including the foundation of the Confederation of the Rhine from various former members of the Empire.

The War of the Fifth Coalition in 1809 had ended with another defeat for the joint forces of the Austrian Empire, Great Britain, Spain, and Portugal against the French and their German allies. Following Napoleon's unsuccessful invasion of Russia in 1812, Prussia joined the countries already at war with France to begin the War of the Sixth Coalition in March 1813.[3] During the early part of the campaign, the allied forces against Napoleon suffered defeats at Großgörschen (2 May) and Bautzen, being driven back to the river Elbe. However, due to lack of training in his newly-recruited soldiers, Napoleon was unable to take full advantage of his victories, allowing his enemies to regroup.[4] Following a ceasefire, Austria rejoined the Coalition on 17 August. The French advantage in numbers was now reversed, with the Coalition forces counting 490,000 soldiers to Napoleon's 440,000.[5]

Between 16–19 October 1813, the Battle of the Nations outside Leipzig was the decisive one in the war, cementing the French defeat and temporarily ending Napoleon's rule. The Emperor was exiled to Elba in May 1814, but briefly returned to power the following year, before being permanently banished following his defeat at the Battle of Waterloo. The Battle of the Nations was fought between France and their German allies against a coalition of Russian, Austrian, Prussian, and Swedish forces. About half a million soldiers were involved and at the end of the battle, around 110,000 men had lost their lives, with many more dying in the days after in field hospitals in and around the city. The scope of the fighting was unprecedented.[6]

Construction

In 1814 proposals to build a monument to commemorate the battle were made. Among the supporters of the project, author Ernst Moritz Arndt called for the construction of "a large and magnificent (monument), like a colossus, a pyramid, or the cathedral of Cologne". Architect Friedrich Weinbrenner created a design for the monument that ultimately was not used.[7]

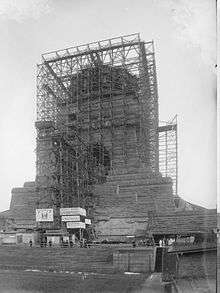

In 1863, commemorating the 50th anniversary of the battle, a foundation stone was placed, but the memorial was not built.[8] Clemens Thieme, a member of the Verein für die Geschichte Leipzigs (Association for the History of Leipzig) learned during a meeting of the association about the past plans to build a monument. Interested in resuming the project, Thieme, who was also a member of the Apollo masonic lodge, proposed the project during a meeting and gained the support of his fellow masons.[9] In 1894, he founded the Deutsche Patriotenbund (Association of German Patriots) which raised, by means of donations and a lottery, the funds necessary to construct the monument for the 100th anniversary . The following year, the city of Leipzig donated a 40,000-square-metre (9.9-acre) site for the construction.[10] The project was commissioned to Bruno Schmitz, due to his previous works at the Kyffhäuser.[8] The construction began in 1898. The chosen construction site was the spot where Napoleon ordered the retreat of his army.[2] Thieme financed part of the construction as well, and for his complete dedication to the project, he was named an Honorary Citizen of Leipzig.[9]

In 1898, the construction started. 82,000 cubic metres (107,000 cu yd) of earth was moved; 26,500 granite blocks were used and the project resulted in a total cost of 6,000,000ℳ (27,886,558€ in 2020),[2] the monument was finished in 1913.[11] On the 18th of October 1913 the Völkerschlachtdenkmal was inaugurated in the presence of about 100 000 people including the emperor Wilhelm II, and all the reigning sovereign rulers of the German states.[12]

Design and concept

Inspired by Weinbrenner's early project,[13] Schmitz constructed the monument over an artificial hill,[2] and selected a pyramidal shape for a clear view of the surroundings.[14] The base is 124 metres (407 ft) square. The main structure, at 91 metres (299 ft), is one of the tallest monuments in Europe. It is composed of two storeys. On the first story, a crypt is adorned by eight large statues of fallen warriors, each one next to smaller statues called the Totenwächter (Guardians of the Dead). On the second story, the Ruhmeshalle (Hall of Fame) features four statues, each 9.5 metres (31 ft) tall, representing the four legendary historic qualities ascribed to the German people: bravery, faith, sacrifice, and fertility.[14] The statues of the monument were sculpted by Christian Behrens and his apprentice Franz Metzner,[2] who finished the remaining statues after Behrens's death in 1905.[15] Metzner worked on the sculptures at the top and inside the memorial.[16]

- Crypt of the Monument

- Archangel Michael

Wächterfiguren (guards)

Wächterfiguren (guards) Dome of the memorial

Dome of the memorial- Dome details

The memorial is constructed in granite and sandstone. The cupola is decorated with primitive Germanic shapes, inspired by Egyptian and Assyrian sculpture. Schmitz also planned to create an accompanying complex for ceremonies that would include a court, a stadium and parade grounds. However, only a reflecting pool and two processional avenues were ultimately completed.[17] Surrounding the monument are oaks, a symbol of masculine strength and endurance to the Germanic people of antiquity. The oaks are complemented by evergreens, symbolising feminine fecundity, and they are located in a subordinate position to the oaks.[18] The 12 metres (39 ft) main figure on the front of the memorial represents the archangel Michael, considered the "War god of Germans".[19][20]

The design of the monument was intended to commemorate the spirit of the German folk. Unlike previous monuments that commemorated the achievements of the monarchy, this one was created to commemorate the end of the battle in 1813, the establishment of a German community, and the maturation of the Germans as an organised ethnic group.[14]

From the Nazi Third Reich through the Communist GDR to the present

During the Third Reich, Hitler frequently used the monument as a venue for his meetings in Leipzig.[17] During WW2, an anti-aircraft gun (Flak) position was established on top of the monument. When the US Army captured Leipzig on April 18, 1945, the monument was the last stronghold in the city to surrender. 300 soldiers, men of the Volkssturm and boys of the Hitler Youth under the command of Oberst Hans von Poncet, were holding out in the monument, but after a direct artillery hit inside the structure, von Poncet was convinced to surrender following long negotiations.[21]

During the period of Communist rule in East Germany from 1949 to 1989, the government of the GDR was unsure whether it should allow the monument to stand, since it was considered to represent the steadfast nationalism of the period of the German Empire. Eventually, it was decided that the monument be allowed to remain, since it represented a battle in which Russian and German soldiers had fought together against a common enemy, and was therefore representative of Deutsch-russische Waffenbrüderschaft (Russo-German brotherhood-in-arms) (although some Germans fought on the other side in the battle).

In 1956, the opening ceremony of the Gymnastics and Sports Festival took place in the memorial complex; the authorities stated that the monument could be interpreted as a symbol of "long-standing German-Russian friendship".[22] The festival planners focused the spirit of the celebrations on German history, and the ceremony as a symbol of the desired German union.[23]

Restoration of the monument started in 2003, and is expected to be completed in 2019.[24] The Monument of the Battle of Nations is located in the southeast of Leipzig and can be reached by tram lines 15 and 2 at Völkerschlachtdenkmal.

Later structures inspired by the Monument

- Voortrekker Monument

- Shipka Monument

References

- leipzig-sachsen.de Das Völki, wie das Denkmal von der Bevölkerung Leipzigs gern genannt wird, ist Anziehungspunkt von Touristen aus aller Welt., retrieved March 26, 2014

- Pohlsander; p.170

- Thamer 2013, p. 30.

- Thamer 2013, p. 42.

- Thamer 2013, p. 43.

- Poser 2014, p. 4.

- Pohlsander; p.168

- Pohlsander; p.169

- Hoffmann; p.122

- "The Völkerschlachtdenkmal and its History". Stadtgeschichtliches Museum Leipzig. Retrieved August 23, 2011.

- Kamusella; p.180

- "Völkerschlachtdenkmal in Leipzig, Pyramide des Patrioten" (in German). Hamburg: Der Spiegel. 2013-10-18. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- Koshar; pp.43,44

- Koshar; p.44

- Sembach; p.28

- Sembach; p.38

- Michalski; p.65

- Koshar; p.46

- Eisenschmid, Rainer, ed. (2011). Deutschland, Osten [Germany, East] (in German). Baedeker. p. 328. ISBN 9783829712279.

- Keller & Schmid 1995, p. 9.

- "Kalenderblatt: 19.4.1945 – Das letzte Aufgebot". Spiegel Online. 19 March 2009.

- Johnson; p.37

- Johnson; p.38

- KG, Chemnitzer Verlag und Druck GmbH & Co. "Baugerüste in der Krypta des Völkerschlachtdenkmals fallen". Freiepresse.de. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

Bibliography

- Hoffmann, Stefan-Ludwig (2007). The Politics of Sociability: Freemasonry and German Civil Society, 1840-1918. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-11573-0.

- Kamusella, Tomasz (2007). Silesia and Central European Nationalisms: The Emergence of National and Ethnic Groups in Prussian Silesia and Austrian Silesia, 1848-1918. Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-371-5.

- Koshar, Rudy (2000). From Monuments to Traces: Artifacts of German Memory, 1870-1990. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21768-3.

- Johnson, Molly Wilkinson (2008). Training Socialist Citizens: Sports and the State in East Germany. Studies in Central European Histories. 44. Brill. ISBN 9789004169579.

- Keller, Katrin; Schmid, Hans-Dieter, eds. (1995). "Das Völkerschlachtdenkmal als Gegenstand der Geschichtskultur" [The Battle Monument as the subject of history culture]. Vom Kult zur Kulisse [The cult of scenery] (in German). Leipziger Universitätsverlag. ISBN 978-3-929031-60-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Michalski, Sergiusz (1998). Public Monuments: Art in Political Bondage, 1870-1997. Reaktion Books. ISBN 9781861890252.

- Pohlsander, Hans (2008). National Monuments and Nationalism in 19th Century Germany. New German-American Studies. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3-03911-352-1.

- Poser, Steffen (2014). Monument to the Battle of the Nations: Short Guide. Leipzig: Passage-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-938543-73-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sembach, Klaus-Jürgen (2002). Art Nouveau. Taschen. ISBN 978-3-8228-2022-3.

- Tebbe, Jason (2010). "Revision and "Rebirth": Commemoration of the Battle of Nations in Leipzig". German Studies Review. 33 (3): 618–640. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- Thamer, Hans-Ulrich (2013). Die Völkerschlacht bei Leipzig: Europas Kampf gegen Napoleon [The Battle of the Nations at Leipzip: Europe's Battle Against Napoleon] (in German). Munich: C.H. Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-64610-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Völkerschlachtdenkmal. |

- "Monument to the Battle of the Nations". Stadtgeschichtliches Museum Leipzig (City-Historical Museum Leipzig).(Quicktime required)

- "Homepage of the monument's supporters". Voelkerschlachtdenkmal (in German). Archived from the original on 2009-04-23.

- "Homepage of the annual bathtub races" (in German). Archived from the original on 2005-12-15.

- "Homepage of the choir of the Monument" (in German).

- "7 panorama views and information". Virtualcity Leipzig.

- "Völkerschlachtdenkmal in the context of Metzer's career, with photos". Waltlockley.com. Archived from the original on 2008-11-21.