Monoidal category

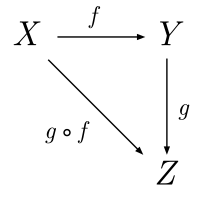

In mathematics, a monoidal category (or tensor category) is a category equipped with a bifunctor

that is associative up to a natural isomorphism, and an object I that is both a left and right identity for ⊗, again up to a natural isomorphism. The associated natural isomorphisms are subject to certain coherence conditions, which ensure that all the relevant diagrams commute.

The ordinary tensor product makes vector spaces, abelian groups, R-modules, or R-algebras into monoidal categories. Monoidal categories can be seen as a generalization of these and other examples. Every (small) monoidal category may also be viewed as a "categorification" of an underlying monoid, namely the monoid whose elements are the isomorphism classes of the category's objects and whose binary operation is given by the category's tensor product.

A rather different application, of which monoidal categories can be considered an abstraction, is that of a system of data types closed under a type constructor that takes two types and builds an aggregate type; the types are the objects and is the aggregate constructor. The associativity up to isomorphism is then a way of expressing that different ways of aggregating the same data—such as and —store the same information even though the aggregate values need not be the same. Identity objects are analogous to algebraic operations addition (type sum) and multiplication (type product). For type product - identity object is the unit , it trivially fully inhabits its type, so there is only one inhabitant of the type, and that is why a product with it is always isomorphic to the other operand. For type sum, the identity object is the void type, which stores no information and its inhabitants impossible to address. The concept of monoidal category does not presume that values of such aggregate types can be taken apart; on the contrary, it provides a framework that unifies classical and quantum information theory.[1]

In category theory, monoidal categories can be used to define the concept of a monoid object and an associated action on the objects of the category. They are also used in the definition of an enriched category.

Monoidal categories have numerous applications outside of category theory proper. They are used to define models for the multiplicative fragment of intuitionistic linear logic. They also form the mathematical foundation for the topological order in condensed matter. Braided monoidal categories have applications in quantum information, quantum field theory, and string theory.

Formal definition

A monoidal category is a category equipped with a monoidal structure. A monoidal structure consists of the following:

- a bifunctor called the tensor product or monoidal product,

- an object called the unit object or identity object,

- three natural isomorphisms subject to certain coherence conditions expressing the fact that the tensor operation

- is associative: there is a natural (in each of three arguments , , ) isomorphism , called associator, with components ,

- has as left and right identity: there are two natural isomorphisms and , respectively called left and right unitor, with components and .

Note that a good way to remember how and act is by alliteration; Lambda, , cancels the identity on the left, while Rho, , cancels the identity on the right.

The coherence conditions for these natural transformations are:

- for all , , and in , the pentagon diagram

This is one of the main diagrams used to define a monoidal category; it is perhaps the most important one.

This is one of the main diagrams used to define a monoidal category; it is perhaps the most important one.

- commutes;

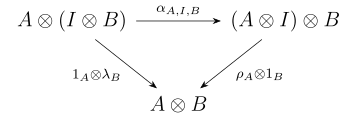

- for all and in , the triangle diagram

- commutes;

A strict monoidal category is one for which the natural isomorphisms α, λ and ρ are identities. Every monoidal category is monoidally equivalent to a strict monoidal category.

A lax monoidal category (or properly, ) consist of

- a category

- for each a functor called n-fold tensor and written

- for each and double sequence of objects of a map

- for each object a map with the following properties:

- is a natural in a each of the and is natural in .

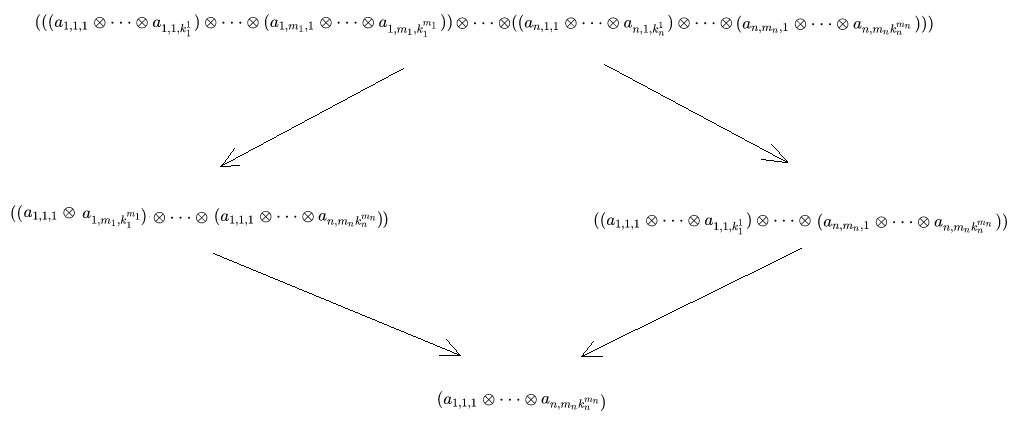

- associativity: for any and triple sequence of objects, the diagram

commutes, where the double sequences are

- identity for any and sequence of objects, the diagrams

commute.[2]

Examples

- Any category with finite products can be regarded as monoidal with the product as the monoidal product and the terminal object as the unit. Such a category is sometimes called a cartesian monoidal category. For example:

- Set, the category of sets with the Cartesian product, any particular one-element set serving as the unit.

- Cat, the category of small categories with the product category, where the category with one object and only its identity map is the unit.

- Dually, any category with finite coproducts is monoidal with the coproduct as the monoidal product and the initial object as the unit. Such a monoidal category is called cocartesian monoidal

- R-Mod, the category of modules over a commutative ring R, is a monoidal category with the tensor product of modules ⊗R serving as the monoidal product and the ring R (thought of as a module over itself) serving as the unit. As special cases one has:

- K-Vect, the category of vector spaces over a field K, with the one-dimensional vector space K serving as the unit.

- Ab, the category of abelian groups, with the group of integers Z serving as the unit.

- For any commutative ring R, the category of R-algebras is monoidal with the tensor product of algebras as the product and R as the unit.

- The category of pointed spaces (restricted to compactly generated spaces for example) is monoidal with the smash product serving as the product and the pointed 0-sphere (a two-point discrete space) serving as the unit.

- The category of all endofunctors on a category C is a strict monoidal category with the composition of functors as the product and the identity functor as the unit.

- Just like for any category E, the full subcategory spanned by any given object is a monoid, it is the case that for any 2-category E, and any object C in Ob(E), the full 2-subcategory of E spanned by {C} is a monoidal category. In the case E = Cat, we get the endofunctors example above.

- Bounded-above meet semilattices are strict symmetric monoidal categories: the product is meet and the identity is the top element.

- Any ordinary monoid is a small monoidal category with object set , only identities for morphisms, as tensorproduct and as its identity object. Conversely, the set of isomorphism classes (if such a thing makes sense) of a monoidal category is a monoid w.r.t. the tensor product.

Monoidal preorders

Monoidal preorders, also known as "preordered monoids", are special cases of monoidal categories. This sort of structure comes up in the theory of string rewriting systems, but it is plentiful in pure mathematics as well. For example, the set of natural numbers has both a monoid structure (using + and 0) and a preorder structure (using ≤), which together form a monoidal preorder, basically because and implies . We now present the general case.

It's well known that a preorder can be considered as a category C, such that for every two objects , there exists at most one morphism in C. If there happens to be a morphism from c to c' , we could write , but in the current section we find it more convenient to express this fact in arrow form . Because there is at most one such morphism, we never have to give it a name, such as . The reflexivity and transitivity properties of an order are respectively accounted for by the identity morphism and the composition formula in C. We write iff and , i.e. if they are isomorphic in C. Note that in a partial order, any two isomorphic objects are in fact equal.

Moving forward, suppose we want to add a monoidal structure to the preorder C. To do so means we must choose

- an object , called the monoidal unit, and

- a functor , which we will denote simply by the dot "", called the monoidal multiplication.

Thus for any two objects we have an object . We must choose and to be associative and unital, up to isomorphism. This means we must have:

- and .

Furthermore, the fact that · is required to be a functor means—in the present case, where C is a preorder—nothing more than the following:

- if and then .

The additional coherence conditions for monoidal categories are vacuous in this case because every diagram commutes in a preorder.

Note that if C is a partial order, the above description is simplified even more, because the associativity and unitality isomorphisms becomes equalities. Another simplification occurs if we assume that the set of objects is the free monoid on a generating set . In this case we could write , where * denotes the Kleene star and the monoidal unit I stands for the empty string. If we start with a set R of generating morphisms (facts about ≤), we recover the usual notion of semi-Thue system, where R is called the "rewriting rule".

To return to our example, let N be the category whose objects are the natural numbers 0, 1, 2, ..., with a single morphism if in the usual ordering (and no morphisms from i to j otherwise), and a monoidal structure with the monoidal unit given by 0 and the monoidal multiplication given by the usual addition, . Then N is a monoidal preorder; in fact it is the one freely generated by a single object 1, and a single morphism 0 ≤ 1, where again 0 is the monoidal unit.

Properties and associated notions

It follows from the three defining coherence conditions that a large class of diagrams (i.e. diagrams whose morphisms are built using , , , identities and tensor product) commute: this is Mac Lane's "coherence theorem". It is sometimes inaccurately stated that all such diagrams commute.

There is a general notion of monoid object in a monoidal category, which generalizes the ordinary notion of monoid from abstract algebra. Ordinary monoids are precisely the monoid objects in the cartesian monoidal category Set. Further, any strict monoidal category can be seen as a monoid object in the category of categories Cat (equipped with the monoidal structure induced by the cartesian product).

Monoidal functors are the functors between monoidal categories that preserve the tensor product and monoidal natural transformations are the natural transformations, between those functors, which are "compatible" with the tensor product.

Every monoidal category can be seen as the category B(∗, ∗) of a bicategory B with only one object, denoted ∗.

A category C enriched in a monoidal category M replaces the notion of a set of morphisms between pairs of objects in C with the notion of an M-object of morphisms between every two objects in C.

Free strict monoidal category

For every category C, the free strict monoidal category Σ(C) can be constructed as follows:

- its objects are lists (finite sequences) A1, ..., An of objects of C;

- there are arrows between two objects A1, ..., Am and B1, ..., Bn only if m = n, and then the arrows are lists (finite sequences) of arrows f1: A1 → B1, ..., fn: An → Bn of C;

- the tensor product of two objects A1, ..., An and B1, ..., Bm is the concatenation A1, ..., An, B1, ..., Bm of the two lists, and, similarly, the tensor product of two morphisms is given by the concatenation of lists. The identity object is the empty list.

This operation Σ mapping category C to Σ(C) can be extended to a strict 2-monad on Cat.

Specializations

- If, in a monoidal category, and are naturally isomorphic in a manner compatible with the coherence conditions, we speak of a braided monoidal category. If, moreover, this natural isomorphism is its own inverse, we have a symmetric monoidal category.

- A closed monoidal category is a monoidal category where the functor has a right adjoint, which is called the "internal Hom-functor" . Examples include cartesian closed categories such as Set, the category of sets, and compact closed categories such as FdVect, the category of finite-dimensional vector spaces.

- Autonomous categories (or compact closed categories or rigid categories) are monoidal categories in which duals with nice properties exist; they abstract the idea of FdVect.

- Dagger symmetric monoidal categories, equipped with an extra dagger functor, abstracting the idea of FdHilb, finite-dimensional Hilbert spaces. These include the dagger compact categories.

- Tannakian categories are monoidal categories enriched over a field, which are very similar to representation categories of linear algebraic groups.

References

- Baez, John; Stay, Mike (2011). "Physics, topology, logic and computation: a Rosetta Stone". In Coecke, Bob (ed.). New Structures for Physics. Lecture Notes in Physics. 813. Springer, Berlin. pp. 95–172. arXiv:0903.0340. ISBN 9783642128219. ISSN 0075-8450.

- Tom Leinster - Higher operads, Higher Categories.

- Joyal, André; Street, Ross (1993). "Braided Tensor Categories". Advances in Mathematics 102, 20–78.

- Joyal, André; Street, Ross (1988). "Planar diagrams and tensor algebra".

- Kelly, G. Max (1964). "On MacLane's Conditions for Coherence of Natural Associativities, Commutativities, etc." Journal of Algebra 1, 397–402

- Kelly, G. Max (1982). Basic Concepts of Enriched Category Theory (PDF). London Mathematical Society Lecture Note Series No. 64. Cambridge University Press.

- Mac Lane, Saunders (1963). "Natural Associativity and Commutativity". Rice University Studies 49, 28–46.

- Mac Lane, Saunders (1998), Categories for the Working Mathematician (2nd ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag.

- Monoidal category in nLab