Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadani

Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadani (Persian: میر سید علی همدانی; 1314–1384) was a Persian Sūfī of the Kubrawiya order, a poet and a prominent Muslim scholar.[1][2] He was born in Hamadan, and was buried in Khatlan Tajikistan.[3] He was known as Shāh-e-Hamadān ("King of Hamadān"), Amīr-i Kabīr ("the Great Commander"), and Ali Sani ("second Ali").[4]

Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadani | |

|---|---|

میر سید علی همدانی | |

| Title | Second Ali of Kashmir |

| Personal | |

| Born | 714 AH (1314 AD) Hamadān, Persia |

| Died | 786 AH (1384 AD) Khatlon, Tajikistan |

| Religion | Islam |

| Part of a series on Islam Sufism |

|---|

|

List of sufis |

|

|

Early life

The title "Sayyid" indicates that he was a descendant of Muhammad, possibly from both sides of his family.[5]

Hamadani spent his early years under the tutelage of Ala ud-Daula Simnani, a famous Kubrawiya saint from Semnan, Iran. Despite his teacher's opposition to Ibn Arabi's explication of the wahdat al-wujud ("unity of existence"), Hamadani wrote Risala-i-Wujudiyya, a tract in defense of that doctrine, as well as two commentaries on Fusus al-Hikam, Ibn Arabi's work on Al-Insān al-Kāmil. Hamadani is credited with introducing the philosophy of Ibn-Arabi to South Asia.[6]

Travels

Sayyid Ali Hamadani traveled widely – it is said he traversed the known world from East to West three times. In 774 AH/1372 AD Hamadani lived in Kashmir. After Sharaf-ud-Din Abdul Rehman Bulbul Shah, he was the second important Muslim to visit Kashmir. Hamadani went to Mecca, and returned to Kashmir in 781/1379, stayed for two and a half years, and then went to Turkistan by way of Ladakh. He returned to Kashmir for a third time in 785/1383 and left because of ill health. Hamadani is regarded as having brought various crafts and industries from Iran into Kashmir; it is said that he brought with him 700 followers.[6] The growth of the textile industry in Kashmir increased its demand for fine wool, which in turn meant that Kashmiri Muslim groups settled in Ladakh, bringing with them crafts such as minting and writing.[7]

Hamadani traveled and preached Islam in different parts of the world[8] such as Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, China, Syria, and Turkestan.[9]

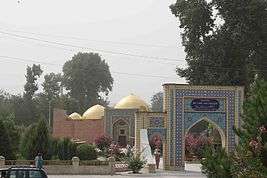

Hamadani died on his way back to Central Asia at a site close to present day Mansehra town in North-West Pakistan.[10] His body was carried by his disciples to Khatlan, Tajikistan, where his shrine is located.[6]

Influence

His disciple Sayyid Ishaq al-Khatlani was in turn the master of Shah Syed Muhammad Nurbakhsh Qahistani.[11] He wrote the following rules in Zakhirat-ul Maluk to Islamize Kashmir:[12]

- The Muslim ruler shall not allow fresh constructions of Hindu temples and shrines.

- No repairs to the existing Hindu temples and shrines shall be allowed.

- Hindus shall not use Muslim names.

- They shall not ride a harnessed horse.

- They shall not move about with arms.

- They shall not wear rings with diamonds.

- They shall not deal in or eat bacon.

- They shall not exhibit idolatrous images.

- They shall not build houses in neighborhoods of Muslims.

- They shall not dispose of their dead near Muslim graveyards, nor weep nor wail over their dead.

- They shall not deal in or buy Muslim slaves.

- No Muslim traveler shall be refused lodging in the Hindu temples and shrines where he shall be treated as a guest for three days by non-Muslims.

- No non-Muslim shall act as a spy in the Muslim state.

- No problem shall be created for those non-Muslims who, on their own will, show their readiness for Islam.

- Non-Muslims shall honor Muslims and shall leave their assembly whenever the Muslims enter the premises.

- The dress of non-Muslims shall be different from that of Muslims to distinguish themselves.

According to a study by Sambalpur University, Hamadani was responsible for conversion of 37000 Kashmiri people to Islam.[13]

Works

One manuscript (Raza Library, Rampur, 764; copied 929/1523) contains eleven works ascribed to Hamadani (whose silsila runs to Naw'i Khabushani; the manuscript contains two documents associated with him).[14]

- Risalah Nooriyah, is a tract on contemplation

- Risalah Maktubaat, contains Amir-i-Kabir’s letters

- Dur Mu’rifati Surat wa Sirat-i-Insaan, discusses the bodily and moral features of man

- Dur Haqaa’iki Tawbah, deals with the real nature of penitence

- Hallil Nususi allal Fusus, is a commentary on Ibn-ul-‘Arabi’s Fusus-ul-Hikam

- Sharhi Qasidah Khamriyah Fariziyah, is a commentary on the wine-qasidah of ‘Umar ibn ul-Fariz who died in 786 A.H. =1385 A.C.

- Risalatul Istalahaat, is a treatise on Sufic terms and expressions

- ilmul Qiyafah or Risalah-i qiyafah is an essay on physiognomy. A copy of this exists in the United States National Library of Medicine.

- Dah Qa’idah gives ten rules of contemplative life

- Kitabul Mawdah Fil Qurba, puts together traditions on affection among relatives

- Kitabus Sab’ina Fi Fadha’il Amiril Mu’minin, gives the seventy virtues of Hazrat ‘Ali.

- Arba’ina Amiriyah, is forty traditions on man’s future life

- Rawdhtul Firdaws, is an extract of a larger work entitled

- Manazilus Saaliqin, is on Sufi-ism

- Awraad-ul-Fatehah, gives a conception of the unity of God and His attributes

- Chehl Asraar (Forty Secrets), is a collection of forty poems in praise of Allah and The Prophet

- Zakhirat-ul-Muluk, a treatise on political ethics and the rules of good government

Dr. Syed Abdur-Rehman Hamdani in his book “Salar-e-Ajjam” has listed 68 Books and 23 Pamphlets by Shah-e-Hamdan[15]

References

- Al-islam.org

- Ninth Session, Part 2

- Hadith alThaqalayn || Imam Reza (A.S.) Network

- Sir Walter Roper Lawrence (2005). The Valley of Kashmir. Asian Educational Services. p. 292. ISBN 978-81-206-1630-1.

- "HAMADĀNI, SAYYED ʿALI – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2018-12-07.

- Rafiabadi, Hamid Naseem (2003). "World Religions and Islam: A Critical Study, Part 2". Sarup & Sons. pp. 97–105. ISBN 9788176254144.

- Fewkes, Jacqueline H. (2008). Trade and Contemporary Society Along the Silk Road: An Ethno-history of Ladakh. Routledge Contemporary Asia. Routledge. pp. 44–45. ISBN 9781135973094.

- Stellrecht, Irmtraud (1997). The Past in the Present: Horizons of Remembering in the Pakistan. Rüdiger Koppe. ISBN 978-38-96451-52-1.

- Barzegar, Karim Najafi (2005). Intellectual movements during Timuri and Safavid period: 1500–1700 A.D. Delhi: Indian Bibliographies Bureau. ISBN 978-81-85004-66-2.

- S. Manzoor Ali, "Kashmir and early Sufism" Rawalpindi:Sandler Press, 1979.

- Deweese, Devin (2014). "Intercessory Claims of Sufi Communities: Messianic Legitimizing Strategies on the Spectrum of Normativity". In Mir-Kasimov, Orkhan (ed.). Unity in Diversity: Mysticism, Messianism and the Construction of Religious Authority in Islam. Brill. pp. 197–220. ISBN 978-90-04262-80-5.

- "Wailing Kashmir: Seven Migrations of Kashmiri Pandits". 2013.

- Shaikh, Allauddin (1992). "Chapter 6: Libraries in Kashmir". Libraries and librarianship during muslim rule in India An analytical study. Sambalpur University.

- Deweese, Devin (2005). "Two Narratives on Najm al-Din Kubra and Radi al-Din Lala from a Thirteenth-Century Source: Notes on a Manuscript in the Raza Library, Rampur". In Lawson, Todd (ed.). Reason and Inspiration in Islam: Essays in Honour of Hermann Landolt. I.B. Tauris. pp. 298–339. ISBN 9780857716224.

- "Shah Hamdan History".

Bibliography

- John Renard 2005: Historical Dictionary of Sufism (Historical Dictionaries of Religions, Philosophies and Movements, 58), ISBN 0810853426