Mexico City Blues

Mexico City Blues is a poem published by Jack Kerouac in 1959 composed of 242 "choruses" or stanzas. Written between 1954 and 1957, the poem is the product of Kerouac's spontaneous prose, his Buddhism, and his disappointment at his failure to publish a novel between 1950's The Town and the City and 1957's On the Road.[1]

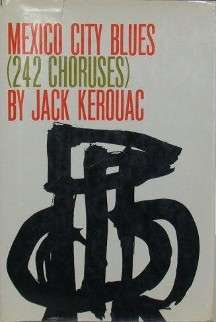

First edition | |

| Author | Jack Kerouac |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Roy Kuhlman |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Grove Press |

Publication date | 1959 |

| Media type | Print (hardback and paperback) |

| OCLC | 20993609 |

| Preceded by | Maggie Cassidy (1959) |

| Followed by | Book of Dreams (1960) |

Writing and publication

Kerouac began writing the choruses that became Mexico City Blues while living with Bill Garver, a heroin addict and friend of William S. Burroughs, in Mexico City in 1955. Written under the influence of marijuana and morphine, choruses were defined only by the size of Kerouac's notebook page. Three of the choruses (52, 53 and 54) are transcriptions of Garver's speech, while others sought to transcribe sounds, and others Kerouac's own thoughts. The choruses include references to real figures including Burroughs and Gregory Corso, as well as religious figures and themes.[2] After finishing Mexico City Blues, while still in Mexico City, Kerouac wrote Tristessa.[3]

In October 1957, after Kerouac achieved fame with On the Road, he sent Mexico City Blues to City Lights Books in the hopes of publication in their Pocket Poets series.[4] In 1958, after the publication of The Dharma Bums, Kerouac's friend Allen Ginsberg tried to sell the book to Grove Press and New Directions Press.[5] It was eventually published by Grove in November 1959.[6]

Critical reception

Rexroth review and contemporary reception

Upon publication a review by the poet Kenneth Rexroth appeared in The New York Times. Rexroth criticized Kerouac's perceived misunderstanding of Buddhism ("Kerouac's Buddha is a dime-store incense burner") and concluded "I've always wondered what ever happened to those wax work figures in the old rubber-neck dives in Chinatown. Now we know; one of them at least writes books."[7] Ginsberg, in observations recorded in Barry Gifford and Lawrence Lee's oral history Jack's Book (1978), attributed Rexroth's "damning, terrible" review and his condemnation of the Beat phenomenon to Rexroth feeling vulnerable as a result of the perception that "he had now 'shown his true colors' by backing a group of unholy, barbarian, no-account, no-good people – Beatnik, unwashed, dirty, badmen of letters who didn't have anything on the ball. So he may have felt vulnerable that he originally had been so friendly, literarily, and had backed us up."[8]

In his monograph on the poem, literary critic James T. Jones describes Rexroth's piece as "a model of unethical behavior in print" which "consigned one of Kerouac's richest works to temporary obscurity", and argued it may have been written in retaliation for perceived poor manners on Kerouac's part, or as an indirect attack on the poet Robert Creeley, a friend of Kerouac's who had an affair with Rexroth's wife.[9] Creeley himself published a more positive review in Poetry,[9] which described the poem as "a series of improvisations, notes, a shorthand of perceptions and memories, having in large part the same word-play and rhythmic invention to be found in [Kerouac's] prose."[10] The poet Anthony Hecht also reviewed Mexico City Blues in The Hudson Review and declared "the proper way to read this book ... is straight through at one sitting."[11] Hecht argued that Kerouac's professed aspiration to be a "jazz poet", amplified by his publishers, was an imposture, and that the book was in fact much more "literary", resembling or drawing on the work of Ezra Pound, William Carlos Williams, Gertrude Stein, E. E. Cummings and James Joyce.[12] Hecht concludes

there is something valuable and beguiling behind the poetry which is as curiously difficult to get at as if the book were translated from another tongue ... But what seems to me to emerge at the end is a voice of remarkable kindness and gentleness, an engaging and modest good humor and a quite genuine spiritual simplicity...[13]

The poet Gary Snyder, a friend of Kerouac's, in 1959 described Mexico City Blues as "the greatest piece of religious poetry I've ever seen."[14]

Later studies

Jones has described Mexico City Blues as

definitive documentation of Kerouac's attempt to achieve both psychic and literary equilibrium. He endeavored to express in a complex, ritualized song as many symbols of his personal conflicts as he could effectively control by uniting them with traditional literary techniques. In this sense, Mexico City Blues is the most important book Kerouac ever wrote, and it sheds light on all his novels by providing a compendium of the issues that most concerned him as a writer, as well as a model for the transformation of conflict into an antiphonal language.[15]

In his book Jack Kerouac: Prophet of the New Romanticism (1976), Robert A. Hipkiss criticizes much of Kerouac's poetry, but identifies Mexico City Blues as probably containing Kerouac's best poetry, and praises the 235th Chorus in particular.[16] Hipkiss compares the 235th Chorus to Robert Frost's "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening", and interprets the chorus, which reads "How do I know that I'm dead / Because I'm alive / And I got work to do ...", as referring to obligations which give purpose to the narrator's life, but which are "painful and not satisfying". Unlike in Frost's poem, in Mexico City Blues "there is no satisfactory putting aside of the death wish by contemplating the 'miles to go before I sleep.'"[17] Hipkiss describes the poem as "an expression of the creative impulse very much for its own sake—a refusal of rules of creation and a celebration, in the act, of the spontaneity inherent in creativity."[18]

In other media

When Bob Dylan and Allen Ginsberg visited Kerouac's hometown of Lowell, Massachusetts as part of the Rolling Thunder Revue tour, they visited Kerouac's grave where Ginsberg recited stanzas from Mexico City Blues. Footage of the two men at the grave was featured in the film Renaldo and Clara (1978). Ginsberg later said that Dylan was already familiar with Mexico City Blues, having read it while living in St. Paul, Minnesota in 1959.[19]

References

- Jones, James T. (2010) [1992]. A Map of Mexico City Blues: Jack Kerouac as Poet (Revised ed.). Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. p. 10. ISBN 0809385988.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McNally, Dennis (1979). Desolate Angel: Jack Kerouac, the Beat Generation, and America. New York: Random House. p. 195. ISBN 0394500113.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McNally 1979, p. 196.

- McNally 1979, p. 243.

- McNally 1979, p. 254.

- McNally 1979, p. 274.

- Rexroth, Kenneth (November 29, 1959). "Discordant and Cool". The New York Times.

- Gifford, Barry; Lee, Lawrence (1999) [1978]. Jack's Book: An Oral Biography of Jack Kerouac. Edinburgh: Rebel Inc. ISBN 086241928X.

- Jones 2010, p. 15.

- Creeley, Robert (June 1961). "Ways of Looking". Poetry: 195.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hecht, Anthony (Winter 1959–60). "The Anguish of the Spirit and the Letter". The Hudson Review. 12 (4): 601. doi:10.2307/3848843. JSTOR 3848843.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hecht 1959–60, p. 602.

- Hecht 1959–60, p. 603.

- McNally 1979, p. 208.

- Jones 2010, p. 4.

- Hipkiss, Robert A. (1976). Jack Kerouac: Prophet of the New Romanticism. Lawrence: The Regents Press of Kansas. p. 81. ISBN 0700601511.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hipkiss 1976, p. 52.

- Hipkiss 1976, p. 94.

- Wilentz, Sean (August 15, 2010). "Bob Dylan, the Beat Generation, and Allen Ginsberg's America". The New Yorker.