Mexican burrowing toad

The Mexican burrowing toad (Rhinophrynus dorsalis) is the only species in the genus Rhinophrynus and the family Rhinophrynidae of order Anura.[2][3] Their distribution stretches from south Texas through Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador to Nicaragua and Costa Rica.[2] R. dorsalis mostly commonly inhabits the subtropical and tropical dry forests within its range characterized by wet and dry seasons, but may also be found during periods of heavy rain in pastures, cultivated field, roadside ditches or other open areas.[4] The family was once more widespread, including species ranging as far north as Canada, but these died out in the Oligocene.[5]

| Mexican burrowing toad | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Anura |

| Family: | Rhinophrynidae |

| Genus: | Rhinophrynus A. M. C. Duméril & Bibron, 1841 |

| Species: | R. dorsalis |

| Binomial name | |

| Rhinophrynus dorsalis A. M. C. Duméril & Bibron, 1841 | |

| Distribution of R. dorsalis (in black) | |

Its name means 'nose-toad', from rhino- (ῥῑνο-), the combining form of the Ancient Greek rhis (ῥίς, 'nose') and phrunē (φρύνη, 'toad').[6]

R. dorsalis for the majority of the year can be found in burrows beneath the surface (fossorial), whose physiology reflects the adaptation to this underground environment. [7][4]

Description

Adults of the Mexican burrowing toad grow to be between 75-85 mm (snout-vent length) or about 3.0 to 3.3 inches[8]. R. dorsalis are sexually dimorphic, with females being larger than males.[4] It is characterized by a short, stout, globular-shaped body and conical-shaped head. [4][9] The color of its smooth skin ranges from shades of dark-gray to maroon-brown on its top surface, which is covered in irregular spots of pale yellow, orange, and red markings and has a red stripe along the center of its back.[4] Keratinized spades on the inside of each hind foot aid it in digging.[4] The snout is covered in epidermal armor of small keratinous spines and the lips are doubled sealed by secretions from submandibular glands.[9] Its eyes are relatively small, and the tympanum is not visible. Unique among the frogs, the Mexican burrowing toad's tongue is projected directly out the front of the mouth, instead of being flipped out, as in all other frogs as a specialization for eating subterranean arthropods, primarily ants and termites.[9]

Ecology and behavior

R. dorsalis are considered “explosive breeders”, also characteristic of other burrowing Anura, whereby many individuals exit their burrows synchronously and converge upon temporary pools of water.[8] For the majority of the year, R. dorsalis lives underground and only emerges with the first heavy rains of the year[7]. The males then float on the surface of the water, partially submerged, and inflate their bodies while calling that will eventually result in most males mating with females using inguinal amplexus.[4][7] Although the mating season of explosive breeders is restricted to a short period each year, R. dorsalis has one of the shortest seasons among amphibians of between 1-3 days, after which they will burrow back into the ground once the environment has dried up and remain until the next breeding season.[7] Intraspecific competition between males for females rarely involves agonistic interactions, but instead relies on acoustic communication. Females of R. dorsalis are thought to choose mates based on characteristics of their mating calls, also referred to as advertisement calls.[7] These calls last 1.36 (± 0.12) seconds and are characterized by a single tone that is upward modulated. This call sounds like a loud, low-pitched "wh-o-o-o-a". Preceding the advertisement call are another type of vocalization known as pre-advertisement marked by a single sound only 0.25 (± 0.09) seconds that instead do not modulate.[7] As a newly documented call, the function of this vocalization type is currently unknown but is thought to play a role in aggression or act as a close-range signal for other males.[7]

When the female is laying eggs, both male and female are underwater. Between 6-12 eggs come out of her cloaca successively, whose sticky surfaces will clump together on the bottom surface.[4] The eggs take only a few days to hatch, and the tadpoles develop over one to three months.

Evolutionary independence

The Mexican burrowing toad is genetically unique in a number of ways. According to EDGE, Mexican burrowing toads are:

The only species, within the only genus of the family Rhinophrynidae, and with over 190 million years of independent evolution, the Mexican burrowing toad is the most evolutionarily distinct amphibian species on Earth today; a fruit bat, polar bear, killer whale, kangaroo and human are all more similar to one another than this species is to any other amphibian.[10]

References

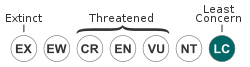

- Georgina Santos-Barrera; Geoffrey Hammerson; Federico Bolaños; Gerardo Chaves; Larry David Wilson; Jay Savage; Gunther Köhler (2010). "Rhinophrynus dorsalis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2010: e.T59040A11873951. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2010-2.RLTS.T59040A11873951.en.

- Frost, Darrel R. (2016). "Rhinophrynidae Günther, 1859". Amphibian Species of the World: an Online Reference. Version 6.0. American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- Vitt, Laurie J.; Caldwell, Janalee P. (2014). Herpetology: An Introductory Biology of Amphibians and Reptiles (4th ed.). Academic Press. p. 476.

- Foster, Mercedes S.; McDiarmid, Roy W. (1983). "Rhinophrynus dorsalis (Alma de vaca, Sapo borracho, Mexican burrowing toad).". In Janzen, D. H. (ed.). Costa Rica Natural History. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 816 pp.

- Zweifel, Richard G. (1998). Cogger, H.G.; Zweifel, R.G. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Reptiles and Amphibians. San Diego: Academic Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-12-178560-4.

- Dodd, C. Kenneth (2013). Frogs of the United States and Canada. 1. The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-4214-0633-6.

- Sandoval, Luis; Barrantes, Gilbert; et al. (2015). "Sexual size dimorphism and acoustical features of the pre-advertisement and advertisement calls of Rhinophrynus dorsalis Duméril & Bibron, 1841 (Anura: Rhinophrynidae)". Mesoamerican Herpetology. 2: 154–166.

- Vitt, Laurie J.; Caldwell, Janalee P. (2013). Herpetology: An Introductory Biology of Amphibians and Reptiles. Elsevier. ISBN 9780123869203.

- Trueb, Linda; Gans, Carl (1983). "Feeding specializations of the Mexican burrowing toad, Rhinophrynus dorsalis (Anura: Rhinophrynidae)". Journal of Zoology. 199 (2): 189–208. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1983.tb02090.x. hdl:2027.42/74489. ISSN 0952-8369.

- "EDGE: Amphibian Species Information". Archived from the original on 2009-08-03. Retrieved 2008-08-25.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rhinophrynus dorsalis. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Rhinophrynus dorsalis |

- "Rhinoprynus dorsalis". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Retrieved May 8, 2006.

- "Rhinophrynidae". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Retrieved May 8, 2006.