McKim, Mead & White

McKim, Mead & White was an American architectural firm that came to define architectural practice, urbanism, and the ideals of the American Renaissance in fin de siècle New York. The firm's founding partners Charles Follen McKim (1847–1909), William Rutherford Mead (1846–1928) and Stanford White (1853–1906) were giants in the architecture of their time, and remain important as innovators and leaders in the development of modern architecture worldwide. They formed a school of classically trained, technologically skilled designers who practiced well into the mid-twentieth century.[1] Arguably, only Frank Lloyd Wright was more important to the identity and character of modern American architecture.[2]

The firm's New York City buildings include Manhattan's former Pennsylvania Station, the Brooklyn Museum, and the main campus of Columbia University. Elsewhere in New York State and New England, the firm designed college, library, school and other buildings such as the Boston Public Library and Rhode Island State House. In Washington, D.C., the firm renovated the West and East Wings of the White House, and designed Roosevelt Hall on Fort Lesley J. McNair and the National Museum of American History. Across the United States, the firm designed buildings in Illinois, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Washington and Wisconsin. Other examples are in Canada, Cuba and Italy. The scope and breadth of their achievement is astounding, considering that many of the technologies and strategies they employed were nascent or non-existent when they began working in the 1880s.[3]

Early years

Charles McKim was the son of a prominent Quaker abolitionist who grew up in West Orange, New Jersey. He attended Harvard College and went to Paris to attend the École des Beaux-Arts, a leading training ground for Americans. William Rutherford Mead, a cousin of president Rutherford B. Hayes, went to Amherst College and trained with Russell Sturgis in Boston. The two formed a partnership with William Bigelow in New York in 1877.

White was born in New York City, the son of Shakespearean scholar Richard Grant White and Alexina Black Mease (1830–1921). His father was a dandy and Anglophile with no money, but a great many connections in New York's art world, including painter John LaFarge, Louis Comfort Tiffany, and Frederick Law Olmsted.

White had no formal architectural training; he began his career at the age of 18 as the principal assistant to Henry Hobson Richardson, the most important American architect of the day and creator of a style recognized today as "Richardsonian Romanesque". He remained with Richardson for six years, playing a major role in the design of the William Watts Sherman House in Newport, Rhode Island, an important Shingle Style work.

White joined the partnership in 1879, and quickly became known as the artistic leader of the firm. McKim's connections helped secure early commissions, while Mead served as the managing partner. Their work applied the principles of Beaux-Arts architecture, with its classical design traditions and training in drawing and proportion, and the related City Beautiful movement after 1893. The designers quickly found wealthy and influential clients amidst the bustle and economic vigor of metropolitan New York.[4]

Initially the firm distinguished itself with innovative Shingle Style summer houses such as the Victor Newcomb house in Elberon, New Jersey (1880-81) the Isaac Bell house in Newport (1883), Rhode Island, and the Joseph Choate house,"Naumkeag," in Lenox, Massachusetts (1885-88).[5] Their status rose when McKim was asked to design the Boston Public Library in 1887, ensuring a new group of institutional clients following its successful completion in 1895. The firm had begun to use classical sources from Modern French, Renaissance and even Roman buildings as sources of inspiration for daring new work.

In 1877 White and McKim led their partners on a "sketching tour" of New England, visiting many of the key houses of Puritan leaders and early masterpieces of the colonial period. Their work began to incorporate influences from these buildings, contributing to a revival of interest in American art and architecture: The Colonial Revival.[6]

The H.A.C. Taylor house in Newport (1882-86) was the first of their designs to use overt quotations from colonial buildings, but many would follow. A less successful but daring variation of a formal Georgian plan was White's house for Commodore William Edgar, also in Newport (1884-86). Rather than traditional red brick or the pink pressed masonry of the Bell house, White tried a tawny, almost brown color, leaving the building neither fish nor fowl.

The partners added talented designers and associates as the 1890s loomed, with Thomas Hastings, John Carrère, Henry Bacon, Joseph M. Wells on the payroll in their expanding office. With a larger staff each partner could have a "studio" of designers at his disposal, rather like the organization of a modern design firm. This increased their capacity for doing bigger and bigger jobs, such as the design of entire college campuses for Columbia and New York Universities, and a massive entertainment complex at Madison Square Garden. They were entering a new phase of outstanding productivity and achievements.

Flowering and major works

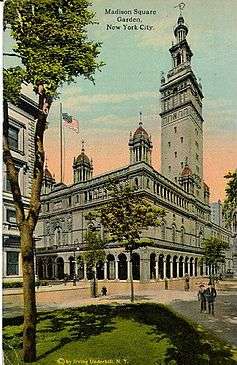

McKim, Mead and White gained prominence as a cultural and artistic force through their construction of Madison Square Garden. White secured the job from the Vanderbilt family, and the other partners brought former clients into the project as investors. The extraordinary building opened its doors in 1890. What had once been a dilapidated arena for horse shows was now a multi-purpose entertainment palace, with a larger arena, a theater, apartments in a Spanish style tower, restaurants, and a roof garden with views both uptown and downtown from 34th Street. White's masterpiece was a testament to his creative imagination, and his taste for the pleasures of city life.[7]

The architects paved the way for many subsequent colleagues by fraternizing with the rich in a number of other settings similar to The Garden, enhancing their social status during the Progressive Era. McKim, Mead and White designed not only the Century Association building (1891), but also many other clubs around Manhattan: the Colony Club, the Metropolitan Club, the Harmonie Club, and the University Club. The latter is certainly the best of its type, standing proudly on Fifth Avenue next to St. Thomas Church (Bertram Goodhue, architect) and near townhouses also designed by the firm. Its magnificent entry hall, library, and dining rooms are a testament to the talents of White and his associates.

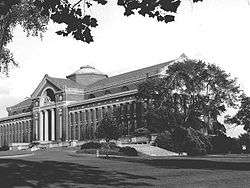

Though White's subsequent life was plagued by scandals, and McKim's by depression and the loss of his second wife, the firm continued to produce magnificent and varied work in New York and abroad. [8] They worked for the titans of industry, transportation and banking, designing not only classical buildings (the New York Herald Building, Morgan Library, Villard Houses, and Rhode Island State Capitol), but also planning factory towns (Echota, near Niagara Falls, New York; Roanoke Rapids, Virginia, and Naugatuck, Connecticut),[9] and working on university campuses (the University of Virginia, Harvard, and Columbia). The magnificent Low Library (1897)at Columbia was in many ways a tribute to Thomas Jefferson's at the University of Virgina, where White added an academic building on the other side of the Lawn.

Some of their later, classical country houses also enhanced their reputation with wealthy oligarchs and critics alike. The Frederick Vanderbilt mansion at Hyde Park (1895-98), New York, and the White's "Rosecliff" for Tessie Oelrichs (1898-1902) in Newport were elegant venues for the society chronicled by Edith Wharton and Henry James. Newly wealthy Americans were seeking the right spouses for their sons and daughters, among them idle aristocrats from European families with dwindling financial resources. When called for, the firm could also deliver a house full of continental antiques and works of art, many acquired by Stanford White from dealers abroad. The Clarence McKay house in Roslyn, New York, was probably the most opulent of these flights of fancy. Though many are gone, some now serve new uses, such as "Florham," in Madison, New Jersey, (1897-1900) now the home of Fairleigh Dickinson University.[10]

New York's enormous Penn Station (1906-10) was the firm's crowning achievement, reflecting not only their commitment to new technological advances, but also to architectural history stretching back to Greek and Roman times.[11] McKim designed New York's greatest monument to Progressive era ideals of civic dignity, capitalist power, and democratic government, alas lost to the greed of its owners during the 1960s and replaced by the ironically named Madison Square Garden arena and an underground maze of public spaces. The firm's final contribution to the city was the Municipal Building (1910-13) adjacent to City Hall, tragically built following the deaths of both White (1906) and McKim (1909) and the financial collapse of the original partnership.[12]

Later partnerships

The firm retained its name long after the deaths of founding partners White (1906), McKim (1909), and Mead (1928). The major partners became William M. Kendall and Lawrence Grant White, Stanford's son. [13]

Among the firm's final works under the name McKim, Mead & White was the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. Designed primarily by partner James Kellum Smith, it opened in 1964.[14]

Smith died in 1961, and the firm was soon renamed Steinmann, Cain and White. In 1971, it became Walker O. Cain and Associates.[15]

Selected works

New York City

| Building | Location | Year | Features | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Villard Houses | Manhattan | 1884 |  | |

| Harvard Club of New York | Manhattan | 1894 | ||

| 169 West 83rd Street | Manhattan | 1885 | for David H. King, Romanesque revival | |

| 900 Broadway | Manhattan | 1897 |  | |

| Former New York Life Insurance Company Building | Manhattan | 1894–98 | White marble Renaissance palazzo-style building. MMW took over the commission upon the death of Stephen D. Hatch in 1894.[16] |  |

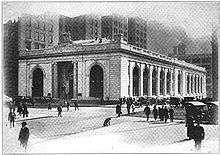

| Madison Square Garden II | Manhattan | 1890 | second of four buildings known by this name; razed in 1925 |  |

| Century Club | Manhattan | 1891 |  | |

| Cable Building | Manhattan | 1893 |  | |

| West End Collegiate Church | Manhattan | 1892 | Verify Attribution | |

| Washington Arch, Washington Square Park | Manhattan | 1892 | ||

| Metropolitan Club | Manhattan | 1893 |  | |

| Prospect Park | Brooklyn | 1895–1900 | Various features including Parade Place on Lookout Hill, Peristyle, Park Circle granite fixtures, Lullwater Bridge, 1895 Maryland Monument on Lookout Hill | |

| Morningside Heights campus, Columbia University | Manhattan | 1893–1900 | general design and individual buildings including Low Memorial Library, Philosophy Hall, John Jay Hall, Avery Hall, Hamilton Hall |  |

| University Heights campus, New York University | Bronx | 1891–1900 | including Hall of Fame for Great Americans 1900, now site of Bronx Community College | |

| Harmonie Club | Manhattan | 1905 | ||

| New York Herald Building | Manhattan | 1895 | razed in 1921 | |

| Brooklyn Museum | Brooklyn | 1895 | ||

| University Club of New York | Manhattan | 1899 | ||

| New York Public Library branches | Manhattan and the Bronx | 1902-1914 | designed 11 branches including Hamilton Grange Branch 1905–1906, 115th Street Branch 1907–1908 | |

| Morgan Library & Museum | Manhattan | 1903 | expanded in 1928 | |

| IRT Powerhouse | Manhattan | 1904 |  | |

| 390 Fifth Avenue | Manhattan | 1906 | for the Gorham Manufacturing Company | |

| Prison Ship Martyrs' Monument | Brooklyn | 1908 |  | |

| Knickerbocker Trust Building | Manhattan | 1909 | now razed | |

| The Manhattan Municipal Building | Manhattan | 1909–1915 |  | |

| Pennsylvania Station | Manhattan | 1910 | above-ground portion razed in 1963 |  |

| 998 Fifth Avenue | Manhattan | 1912 | ||

| Bellevue Hospital Center | Manhattan | 1912 |  | |

| James Farley Post Office | Manhattan | 1913 | often regarded as the architectural twin of New York City's Pennsylvania Station | |

| Racquet and Tennis Club | Manhattan | 1916–1918 |  | |

| Hotel Pennsylvania | Manhattan | 1919 | .jpg) | |

| Town Hall | Manhattan | 1921 |  | |

| 110 Livingston Street | Brooklyn | 1926 | former Elks Lodge, former headquarters of New York City Department of Education |  |

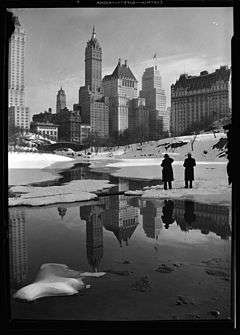

| Savoy-Plaza Hotel | Manhattan | 1927 | razed in 1965 |  |

| Liggett Hall, Governors Island | Manhattan | 1929 | ||

| DeKalb Hall and Information Science Center | Brooklyn | 1955 | ||

| North Hall at Pratt Institute | Brooklyn | 1957 | ||

New England and New York State

| Building | Location | Year | Features | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newport Casino | Newport, Rhode Island | 1880 |  | |

| John Howard Whittemore House | Naugatuck, Connecticut | 1880s | [17] | |

| Isaac Bell House | Newport, Rhode Island | 1881–1883 | ||

| Cyrus McCormick summer estate, shingle-style | Richfield Springs, New York | 1882 | razed 1957 | |

| Emdalar Castle - Tickner Estate | South Kingstown, Rhode Island | 1883 | Restored to its original condition in 2014. | |

| Narragansett Pier Casino | Narragansett, Rhode Island | 1883 |  | |

| Salem School (Naugatuck, Connecticut) | Naugatuck, Connecticut | 1884 | [17] |  |

| Wolf's Head Society, "Old Hall", Yale University | New Haven, Connecticut | 1884 |  | |

| Charles J. Osborn Residence | Mamaroneck, New York | 1885 | Mamaroneck Beach and Yacht Club since 1952[18] | |

| "Four Chimneys" Mansion | New Rochelle, New York | ? | ||

| John F. Andrew Mansion, 32 Hereford Street | Boston, Massachusetts | 1886 | ||

| William G. Low House | Bristol, Rhode Island | 1887 | epitome of Shingle Style architecture; razed 1962 |  |

| Algonquin Club | Boston, Massachusetts | 1888 | ||

| Johnston Gate, Harvard University | Cambridge, Massachusetts | 1889 | ||

| Fayerweather Hall, Amherst College | Amherst, Massachusetts | 1890 | ||

| Walker Art Building, Bowdoin College | Brunswick, Maine | 1894 | ||

| Whittemore Memorial Library | Naugatuck, Connecticut | 1894 | [17] | |

| Adams Power Plant Transformer House | Niagara Falls, New York | 1895 |  | |

| Boston Public Library | Boston, Massachusetts | 1895 |  | |

| Dudley Pickman House, 303 Commonwealth Avenue (Bay Bay) | Boston, Massachusetts | 1895 | ||

| Reid Hall, Manhattanville College | Purchase, New York | 1895 | ||

| Rhode Island State House | Providence, Rhode Island | 1895–1904 | .jpg) | |

| Garden City Hotel | Garden City, New York | 1895 | burned 1899 | |

| House for Frederick Vanderbilt, "Hyde Park" | Hyde Park, New York | 1895–1898 |  | |

| Woodlea | Briarcliff Manor, New York | 1895 | now Sleepy Hollow Country Club |  |

| James L. Breese House "The Orchard" | Southampton, New York | 1897-1906 | ||

| Rosecliff | Newport, Rhode Island | 1898–1902 | ||

| Harbor Hill | Long Island, New York | 1899–1902 | razed 1947 | |

| Symphony Hall | Boston, Massachusetts | 1900 |  | |

| Hill-Stead Museum | Farmington, Connecticut | 1901 | estate of Alfred Atmore Pope, designed with Theodate Pope Riddle | |

| Astor Courts | Rhinebeck, New York | 1902–1904 | estate of John Jacob Astor | |

| Rockefeller Hall, Brown University | Providence, Rhode Island | 1904 | now Faunce House | |

| Naugatuck High School | Naugatuck, Connecticut | 1904 | Hillside Middle School since 1959 | |

| Waterbury Union Station | Waterbury, Connecticut | 1909 | Renaissance Revival style featuring a clock tower modeled on the Torre del Mangia in Siena, Italy[19] | |

| Plymouth Rock portico | Plymouth, Massachusetts | 1920 |  | |

| Foster Hall, University at Buffalo South Campus | Buffalo, New York | 1921 | ||

| Harvard Business School | Boston, Massachusetts | 1925 | ||

| Ira Allen Chapel, University of Vermont | Burlington, Vermont | 1925 |  | |

| Olin Memorial Library, Wesleyan University | Middletown, Connecticut | 1925 | ||

| Memorial Chapel, Union College | Schenectady, New York | 1925 | ||

| Lincoln Alliance Building | Rochester, New York | 1926 | ||

| Rochester Savings Bank | Rochester, New York | 1927 |  | |

| George Eastman House | Rochester, New York | c.1903 | Eastman hired McKim, Mead & White to design the interior of his Georgian Colonial Revival Mansion which was nearly an exact, large scale duplicate of the Robert Root House that was built by the firm in Buffalo, New York c.1894[20] | |

| Burlington City Hall | Burlington, Vermont | 1928 | ||

| Levermore Hall, Blodgett Hall, and Woodruff Hall, Adelphi University | Garden City, New York | 1929 | ||

| Schenectady City Hall | Schenectady, New York | 1931–1933 |  | |

| The Little Red Schoolhouse, Amherst College | Amherst, Massachusetts | 1937 | ||

| Housatonic Railroad Station[21] | Stockbridge, Massachusetts | 1893 | English Gothic Revival style, stone | |

| New York Central Railroad Station | Ardsley-on-Hudson, New York | 1895 | Shingle Style with Tudor and Romanesque Revival elements[21] | |

| Park Lane Apartments | Mount Vernon, New York | 1929 | ||

| The Cedars/Lord's Castle Remodel | Piermont, New York | 1892 | "The original gable ends were stepped, the pointy "Gothick" windows were Edwardianized, the wooden porches reconstructed in stone, the tower on the west capped with a conical roof, the forest of delicate chimney pots combined and bulked up, and the reconfigured interior given heavy doses of classical columns, balusters, dadoes, fireplaces and moldings." [22][23] |

New Jersey

| Building | Location | Year | Features | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Florham Campus, Fairleigh Dickinson University | Madison and Florham Park, New Jersey | 1897 | originally "Florham," the estate of Hamilton Twombly and Florence Vanderbilt, one of many Vanderbilt houses | |

| Orange Public Library | Orange, New Jersey | 1901 |  | |

| St. Peter's Episcopal Church | Morristown, New Jersey | 1889-1913 | English-medieval style parish church. |  |

| Hurstmont | Morristown, New Jersey | 1902-3 | Private estate. | |

| FitzRandolph Gate | Princeton, New Jersey | 1905 | The official entrance of Princeton University |  |

| University Cottage Club, Princeton University | Princeton, New Jersey | 1906 | One of the Eating clubs at Princeton University | |

| Pennsylvania Station | Newark, New Jersey | 1935 | Art Deco style[21] |  |

Washington, D.C.

| Building | Location | Year | Features | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White House, West Wing and East Wing | 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW | 1903 | Renovation |  |

| Roosevelt Hall, National War College | Fort Lesley J. McNair | 1903–1907 |  | |

| National Museum of American History | 1300 Constitution Avenue NW | 1964 | ||

| Patterson Mansion | 15 Dupont Circle NW | 1903 |  | |

| St. John's Church, Lafayette Square | 1525 H Street NW | 1919 | Renovation |  |

| Pedestal, Jeanne d'Arc[24] | Meridian Hill Park | 1922 | Measures about 10 feet long and 6 feet high | |

Other U.S. locations

Other countries

| Building | Location | Year | Features | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

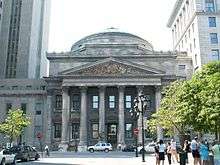

| Bank of Montreal Head Office | Montreal, Quebec, Canada | 1901–1905 | additions |  |

| Bank of Montreal Building | Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada | 1913 | ||

| American Academy in Rome Main Building | Rome, Italy | 1914 | ||

| Hotel Nacional de Cuba | Havana, Cuba | 1930 | ||

Notable architects who worked for McKim, Mead & White

- Henry Bacon – worked at the firm from about 1886 through 1897; left with fellow employee James Brite to open their own office.

- William A. Boring – worked at the firm in 1890 before forming a separate partnership with Edward Lippincott Tilton.

- Charles Lewis Bowman – a draftsman at the firm until 1922, noted for his large number of private residences throughout Westchester County, New York including Bronxville, Pelham Manor, Mamaroneck and New Rochelle.

- A. Page Brown - worked with the firm beginning in the 1880s; went to California, where he was known for the San Francisco Ferry Building.

- Walker O. Cain – worked at the firm; he took it over in 1961 and renamed it several times.

- J.E.R. Carpenter – worked at the firm for several years before designing much of upper Fifth and Park Avenues, including 907 Fifth Avenue, 825 Fifth Avenue, 625 Park Avenue, 550 Park Avenue and the Lincoln Building on 42nd Street.

- John Merven Carrère (1858–1911) – worked with McKim, Mead & White from 1883 through 1885, then joined Thomas Hastings to form the firm Carrère and Hastings.

- Thomas Harlan Ellett (1880–1951).

- Cass Gilbert – worked with the firm until 1882, when he went to work with James Knox Taylor; later designed many notable structures, among them the George Washington Bridge and the Woolworth Building.

- Arthur Loomis Harmon – later of Shreve, Lamb and Harmon.

- Thomas Hastings (1860–1929) – of Carrère and Hastings, worked with McKim, Mead & White from 1883 through 1885.

- John Galen Howard (1864-1931)

- John Mead Howells (1868-1959)

- William Mitchell Kendall (1856 – 1941), worked with the firm from 1882 until his death.

- Harrie T. Lindeberg – started at the firm in 1895 as an assistant to Stanford White and remained with the firm until White's death in 1906.

- Austin W. Lord – worked with the firm in 1890-94 on designs for Brooklyn Museum of Arts and Sciences, the Metropolitan Club, and buildings at Columbia University

- Harold Van Buren Magonigle (1867-1935)

- Albert Randolph Ross

- Philip Sawyer (1868-1949)

- James Kellum Smith (1893–1961) – a member of the firm from 1924 to 1961; full partner in 1929, and the last surviving partner of MM&W. He primarily designed academic buildings, but his last major work was the National Museum of American History.

- Egerton Swartwout of Tracy and Swartwout – both Tracy and Swartwout worked together for the firm on multiple projects prior to starting their own practice.

- Edward Lippincott Tilton – helped design the Boston Public Library in 1890 before leaving with Boring.

- Robert von Ezdorf – took over much of the firm's business after White's death.

- Joseph Morrill Wells (1853–1890) – worked as firm's first Chief Draftsman from 1879–90; often considered to be the firm's "fourth partner", and largely responsible for its Renaissance Revival designs in 1880s.

- William M. Whidden – worked at the firm from at least 1882 until 1888; projects included the Tacoma and Portland hotels in Washington and Oregon, respectively; moved to Portland, Oregon, in 1888 to finish the hotel and established his own firm with Ion Lewis

- York and Sawyer – Edward York (1863–1928) and Philip Sawyer (1868–1949) worked together for the firm before starting their own partnership in 1898.

References

Notes

- See Mark Alan Hewitt, The Architect and the American Country House, 1890-1940, (New Haven, Yale Univ. Press: 1990) pages 15-67,for a discussion of their influence.

- See Robert A.M. Stern, John M. Massengale, and Gregory Gilmartin, New York 1900: metropolitan architecture and urbanism 1893-1915, (New York, Rizzoli International: 1983)

- Samuel G. White, McKim Mead and White: Masterworks (New York, Rizzoli: 2003).

- Leland M. Roth, McKim, Mead and White, Architects, (New York, Harper & Row: 1985)

- See Vincent Scully, Jr. The Shingle Style and the Stick Style: architectural theory and design from Richardson to the origins of Wright (New Haven, Yale Univ. Press: 1971)

- William B. Rhoads, The Colonial Revival, Ph.D. dissertation, Princeton University, (New York, Garland Publishing: 1977) pages 594 and 942.

- Richard Guy Wilson, McKim, Mead and White, architects (New York, Rizzoli: 1983).

- Mosette Broderick, Triumvirate: McKim, Mead & White Art, Architecture, Scandal, and Class in America's Gilded Age (New York, Alfred Knopf: 2010).

- Leland Roth, "Three Factory Towns by McKim, Mead and White," Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians Vol. 38, No. 4 (1979): 317-347.

- See Samuel G. White, The Houses of McKim, Mead and White (New York, Rizzoli: 1998).

- See Steven Parissien, Pennsylvania Station: McKim, Mead and White (London, Phaidon: 1996).

- A Monograph of the Works of McKim, Mead and White, (New York, Architectural Book Publishing Company: 1925).

- "[Mead's] widow receives all the estate of about $250,000"], New York Times (November 27, 1928); "Mrs. Olga Kilenyi Mead, widow,... bequeathed her entire estate to the trustees of Amherst College, Amherst, Massachusetts" in New York Times (April 23, 1936). The money was used to build the Mead Art Building, which was designed by James Kellum Smith of McKim, Mead and White.

- "Mission & History". National Museum of American History. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2018-02-14.

- Patricia McGraw Anderson (1988). The Architecture of Bowdoin College. Brunswick, Maine: Bowdoin College Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 2015-09-09. Retrieved 2013-08-07. http://library.bowdoin.edu/arch/images/lunagallery/libraryluna.shtml Archived 2014-10-18 at the Wayback Machine

- Goeschel, Nancy (February 10, 1987). "Former New York Life Insurance Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- Blackwell, D. and The Naugatuck Historical Society 1996 "Images of Naugatuck". Arcadia Publishing

- Charles J. Osborn Residence

- Potter, Janet Greenstein (1996), Great American Railroad Stations

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-07-31. Retrieved 2020-03-30.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Potter, Janet Greenstein (1996). Great American Railroad Stations. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 94, 154, 164. ISBN 978-0471143895.

- "Piermont Historical Society". piermonthistorysociety.org. Retrieved 2017-10-29.

- "Big Old Houses: I Love This House". New York Social Diary. 2013-01-08. Retrieved 2017-10-29.

- Art and Archaeology. Archaeological Institute of America. 1922.

- "McKelvy House" on the Council of Independent Colleges Historic Campus Architecture Project website

- Bluffton University Digital Imagine Project

- https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/NRHP/80001513_text

Bibliography

- Baker, Paul R. Stanny: The Gilded Life of Stanford White. New York: Free Press, 1989. ISBN 0-02-901781-5

- Broderick, Mosette. Triumvirate: McKim, Mead & White: Art, Architecture, Scandal, and Class in America's Gilded Age New York: Knopf, 2010. ISBN 0-394-53662-2

- McKim, Mead & White. A Monograph of the Work of McKim, Mead & White, 1879-1915. New York: Architectural Book Publishing Co., 1915-1920, 4 volumes. Reprinted as The Architecture of McKim, Mead & White in Photographs, Plans and Elevations, with an introduction by Richard Guy Wilson (New York: Dover Publications, 1990). ISBN 0486265560

- Roth, Leland M. The Architecture of McKim, Mead & White, 1870-1920: A Building List (Garland Reference Library of the Humanities). Garland Publishing (September 1, 1978). 978-0824098506

- Roth, Leland M. McKim, Mead and White, Architects. Harper & Row; First edition (October 1985). 978-0064301367

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to McKim, Mead & White. |

- McKim, Mead & White Selected Works 1879 to 1915, published by Princeton Architectural Press, 2018.

- McKim, Mead & White in Buffalo

- McKim, Mead & White Architectural Records Collection at the New-York Historical Society

- Brooklyn Museum Building Online Exhibition

- McKim, Mead & White architectural records and drawings, circa 1879-1958, held by the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University

.jpg)