Max Roser

Max Roser is an economist, philosopher, and media critic who focusses on large global problems such as poverty, disease, hunger, climate change, war, existential risks, and inequality.[1][2][3][4]

Max Roser | |

|---|---|

| Born | Kirchheimbolanden, Germany |

| Institution | Nuffield College, Oxford Oxford Martin School |

| Field | Economics of income distribution, poverty, global development, global health |

| Influences | Tony Atkinson, Amartya Sen, Angus Deaton, Hans Rosling |

| Website | www www |

He is currently a research director in economics at the University of Oxford.[5]

Life

Roser was born in Kirchheimbolanden, Germany, a small village close to the border with France. As a teenager he won German youth science competition Jugend Forscht.[6]

Der Spiegel reported that he travelled the length of the Nile from the mouth to the source, and that he crossed the Himalayas and the Andes.[7] Roser graduated with degrees in geoscience, economics, and philosophy.[7]

Inequality and poverty researcher Tony Atkinson hired Roser in 2012 at the University of Oxford where he collaborated with Piketty, Morelli, and Atkinson.[8]

Roser is the founder and editor of Our World in Data, a scientific web publication that has the goal to present "research and data to make progress against the world’s largest problems."[9]

He started working on Our World in Data in 2011. During the first years he financed his project by working as a bicycle tour guide around Europe.[10] In 2015 he established a research team at the University of Oxford that is studying global development. About his motivation for this work he wrote "The mission of this work has never changed: from the first days in 2011 Our World in Data focussed on the big global problems and asked how it is possible to make progress against them. The enemies of this effort were also always the same: apathy and cynicism."

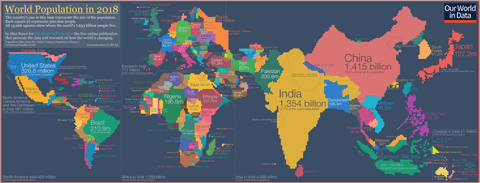

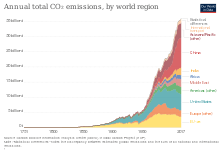

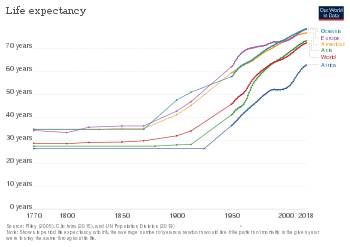

The publication covers a wide range of aspects of development: global health, food provision, the growth and distribution of incomes, violence, rights, wars, technology, education, and environmental changes, among others. The publication makes use of data visualisations which are licensed under Creative Commons and are widely used in research, in the media, and as teaching material.[11] The publication has more than 1.5 million readers every month (November 2018).[12]

In 2019 he was listed in second place among the "World’s Top 50 Thinkers" by Prospect Magazine.[13]

Motivation

In 2011 he founded the open-access research publication Our World in Data as a platform for "research and data on the world's largest problems and how to make progress against them."[9] Roser has said that global poverty, inequality, existential risks, human rights abuse, and humanity's environmental impact are among the world's most severe problems.[2][14]

He is critical of the mass media's excessive focus on single events which he claims is not helpful in understanding "the long-lasting, forceful changes that reshape our world, as well as the large, long-standing problems that continue to confront us."[2][15][16] In contrast to the event-focussed reporting of the news media Roser advocates the adoption of a broader, more holistic perspective on global change:[16] This perspective means looking at inequality and a particular focus on those living in poverty. The focus on the upper classes, especially in historical perspective, is misleading since it is not exposing the hardship of those in the worst living conditions. Secondly, he advocates looking at larger trends in poverty, education, health and violence since these are slowly, but persistently changing the world and are neglected in the reporting of today's mass media.[16] In his focus on slowly evolving structural changes, and dismissal of the media's "event history", he is following the agenda of the French Annales School with their focus on the longue durée.

He is known for his research how global living conditions are changing and his visualisations of these trends.[17][18][19] He has shown that in many societies in the past a large share (over 40%) of children died.[20] Roser maintains that in many important aspects the world has made important progress in improving living conditions and documents this by visualizing the empirical evidence for these long-term trends.[21][22]

In his most-quoted text he writes "For our history to be a source of encouragement we have to know our history. The story that we tell ourselves about our history and our time matters. Because our hopes and efforts for building a better future are inextricably linked to our perception of the past it is important to understand and communicate the global development up to now. […] Freedom is impossible without faith in free people. And if we are not aware of our history and falsely believe the opposite of what is true we risk losing faith in each other."[23]

He said that there are three messages of his work: "The world is much better; The world is awful; The world can be much better" and he writes that "it is because the world is terrible still that it is so important to write about how the world became a better place."[24]

Research

Roser's research is concerned with global problems such as poverty, climate change, child mortality and inequality.

He coauthored a major study of child mortality that was published in Nature in October 2019.[25] It was the first global study that mapped child death on the level of subnational district (17,554 units). The study was described as an important step to make action possible that further reduces child mortality.[26]

In research with Felix Pretis the authors found that the growth rate in CO2 emission intensity exceeded the projections of all climate scenarios.[27]

His research is predominantly concerned with poverty and rising income inequality.[4][28][29] In research with Tony Atkinson, Brian Nolan and others he studied how the benefits from economic growth are distributed.[30][31][32] In research publications with Jesus Crespo Cuaresma he studied the history of international trade and its impact on economic inequality.[33][34]

Roser has criticized the practice of focusing on the international poverty line alone. In his research he suggests a poverty at 10.89 international-$ per day.[35] The researchers say this is the minimum level people needed to have access to basic healthcare. The reason for the low global poverty line is to focus the attention on the world's very poorest population.[36] He proposes using several different poverty lines to understand what is happening to global poverty.

In global health research he studied the impact of poverty on poor health and disease.[37] He also coauthored a textbook on global health.

His most cited article, coauthored with Hannah Ritchie and Esteban Ortiz-Ospina, is concerned with global population growth.[38]

In 2019 he worked with Y Combinator on Our World in Data.[39]

Roser is a regular speaker at conferences where he presents empirical data on how the world is changing.[40][41] Roser regularly consults private sector companies, governments, and the United Nations on global change. He is part of the Statistical Advisory Panel of UNDP.[42] UN Secretary-General António Guterres invites him to internal retreats attended by the heads of the UN institutions to speak about his global development research.[43] Bill Gates referred to Max Roser as "one his favorite economists".[44]

Tina Rosenberg emphasised in The New York Times that Roser’s work presents a "big picture that’s an important counterpoint to the constant barrage of negative world news." Nobel laureate Angus Deaton cites Roser in his book The Great Escape.

All his work is available open access.[45]

Roser's research is regularly cited in academic journals including Science,[46] Nature,[47] and The Lancet.[48][49]

In 2019 Our World in Data won the Lovie Award, the European web award, "in recognition of their outstanding use of data and the internet to supply the general public with understandable data-driven research – the kind necessary to invoke social, economic, and environmental change."[50]

Prospect Magazine listed him as one of the "World’s Top 50 Thinkers."[13] Roser was listed in second place among the World's Top Thinkers in a list that included Martha Nussbaum, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Fields Medal winner Caucher Birkar, and Dani Rodrik.[51]

References

- Rosenberg, Tina (2015-04-09). "Turning to Big, Big Data to See What Ails the World". The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-09-27.

- "About". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2019-08-24.

- "What does data show about the state of the world?". World Economic Forum. Retrieved 2015-09-27.

- Roser, Max (2015-03-27). "Income inequality: poverty falling faster than ever but the 1% are racing ahead". The Guardian. Retrieved 2015-09-27.

- "Dr Max Roser | People". Oxford Martin School. Retrieved 2019-03-10.

- GmbH & Co, Im Fernsehen, Folge 183 (in German)

- Schmundt, Hilmar (2016-01-02). "Statistiken Frohe Botschaft". Der Spiegel. 1. Retrieved 2016-02-19.

- "INET Oxford Highlights 2012-14" (PDF).

- "Our World in Data". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2019-08-24.

- "History of Our World in Data". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2019-10-29.

- "Media Coverage of OurWorldInData.org — Our World in Data". ourworldindata.org. Retrieved 2015-09-27.

- "Ourworldindata.org Analytics - Market Share Stats & Traffic Ranking". www.similarweb.com. Retrieved 2018-11-06.

- Prospect. "The world's top 50 thinkers 2019". Retrieved 2019-08-24.

- "Die Menschheit war früher viel gewalttätiger". Süddeutsche Zeitung. Retrieved 2015-09-27.

- "Dr Max Roser | People | Institute for New Economic Thinking at the Oxford Martin School". www.inet.ox.ac.uk. Institute for New Economic Thinking at the Oxford Martin School. Retrieved 2015-09-27.

- "Data Stories #57: Visualizing Human Development with Max Roser". Data Stories. Retrieved 2015-10-24.

- "Here's how many people have died in war in the last 600 years". Washington Post. Retrieved 2015-09-27.

- "How Obama's optimism about the world explains his foreign policy". Vox. 2015-02-10. Retrieved 2015-09-27.

- "Zbog ebole i terorizma čini nam se da je svijet užasan, ali istina je suprotna: Nikad nam nije bilo ovako dobro". Jutarnji list. Retrieved 2015-09-27.

- "Mortality in the past – around half died as children". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2019-08-24.

- Roser, Max (2014). "It's a cold, hard fact: our world is becoming a better place". Retrieved 2015-09-27.

- "Lowering World Poverty Depends on India". BloombergView. 2015-10-27. Retrieved 2016-03-12.

- "The short history of global living conditions and why it matters that we know it". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2018-11-07.

- "The world is much better; The world is awful; The world can be much better". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2018-11-07.

- Burstein, Roy; Henry, Nathaniel J.; Collison, Michael L.; Marczak, Laurie B.; Sligar, Amber; Watson, Stefanie; Marquez, Neal; Abbasalizad-Farhangi, Mahdieh; Abbasi, Masoumeh; Abd-Allah, Foad; Abdoli, Amir (October 2019). "Mapping 123 million neonatal, infant and child deaths between 2000 and 2017". Nature. 574 (7778): 353–358. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1545-0. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 31619795.

- Bachelet, Michelle (2019-10-16). "Data on child deaths are a call for justice". Nature. 574 (7778): 297. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-03058-6. PMID 31619786.

- Pretis, Felix; Roser, Max (2017-09-15). "Carbon dioxide emission-intensity in climate projections: Comparing the observational record to socio-economic scenarios". Energy. 135: 718–725. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2017.06.119. ISSN 0360-5442. PMID 29033490.

- Roser, Max; Cuaresma, Jesus Crespo (2014-12-01). "Why is Income Inequality Increasing in the Developed World?" (PDF). Review of Income and Wealth. 62: 1–27. doi:10.1111/roiw.12153. ISSN 1475-4991.

- Kaminska, Izabella (2015-01-23). "Give the middle classes their fair share of the pie". Financial Times. ISSN 0307-1766. Retrieved 2015-09-27.

- Nolan, Brian; Roser, Max; Thewissen, Stefan (2019). "GDP Per Capita Versus Median Household Income: What Gives Rise to the Divergence Over Time and how does this Vary Across OECD Countries?". Review of Income and Wealth. 65 (3): 465–494. doi:10.1111/roiw.12362. ISSN 1475-4991.

- Smeeding, Tim; Roser, Max; Nolan, Brian; Kenworthy, Lane; Thewissen, Stefan (2018-05-15). "Rising Income Inequality and Living Standards in OECD Countries: How Does the Middle Fare?". Journal of Income Distribution. 27 (2): 1–23. ISSN 1874-6322.

- Atkinson, Hasell, Morelli, and Roser. "The Chartbook of Economic Inequality – Data on Economic Inequality over the long-run". www.chartbookofeconomicinequality.com. Retrieved 2019-08-24.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Roser, Max; Cuaresma, Jesus Crespo (2016). "Why is Income Inequality Increasing in the Developed World?" (PDF). Review of Income and Wealth. 62 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1111/roiw.12153. ISSN 1475-4991.

- Roser, Max; Cuaresma, Jesus Crespo (2012-07-01). "Borders Redrawn: Measuring the Statistical Creation of International Trade". Rochester, NY. SSRN 2111864. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Olivier Sterck, Max Roser, Mthuli Ncube, Stefan Thewissen. Allocation of development assistance for health: is the predominance of national income justified? Health Policy and Planning, Volume 33, Issue suppl_1, 1 February 2018, Pages i14–i23, https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czw173

- https://ourworldindata.org/extreme-history-methods

- Thewissen, Stefan; Ncube, Mthuli; Roser, Max; Sterck, Olivier (2018-02-01). "Allocation of development assistance for health: is the predominance of national income justified?". Health Policy and Planning. 33 (suppl_1): i14–i23. doi:10.1093/heapol/czw173. ISSN 0268-1080. PMC 5886300. PMID 29415236.

- "Max Roser - Google Scholar Citations". scholar.google.com. Retrieved 2019-11-09.

- "Our World in Data is at Y Combinator". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2019-08-24.

- "Max Roser WIRED 2015 talk: good data will make you an economic optimist (Wired UK)". Wired UK. 2015-10-15. Retrieved 2015-10-24.

- "Roser Speaking – page". www.maxroser.com. Retrieved 2015-10-24.

- "| Human Development Reports". www.hdr.undp.org. Retrieved 2019-11-02.

- "The past and future of global change – Max's slides for his talk at the UN". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2018-11-06.

- @BillGates (21 April 2018). "Data nerds like me will enjoy this @planetmoney episode featuring one of my favorite economists, @MaxCRoser" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- "Max Roser – Economist". www.maxroser.com. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- Nagendra, Harini; DeFries, Ruth (2017-04-21). "Ecosystem management as a wicked problem". Science. 356 (6335): 265–270. doi:10.1126/science.aal1950. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 28428392.

- Topol, Eric J. (January 2019). "High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence". Nature Medicine. 25 (1): 44–56. doi:10.1038/s41591-018-0300-7. ISSN 1546-170X.

- Mpanju-Shumbusho, Winnie; Woo, Hyun Ju; Wegbreit, Jennifer; Tulloch, James; Staley, Kenneth; Singh, Balbir; Shanks, Dennis; Rolfe, Ben; Roh, Michelle (2019-09-21). "Malaria eradication within a generation: ambitious, achievable, and necessary". The Lancet. 394 (10203): 1056–1112. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31139-0. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 31511196.

- Yamin, Alicia Ely; Uprimny, Rodrigo; Periago, Mirta Roses; Ooms, Gorik; Koh, Howard; Hossain, Sara; Goosby, Eric; Evans, Timothy Grant; DeLand, Katherine (2019-05-04). "The legal determinants of health: harnessing the power of law for global health and sustainable development". The Lancet. 393 (10183): 1857–1910. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30233-8. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 31053306.

- "Meet The 2019 Lovie Awards Special Achievement Winners". The Lovie Awards. 2019-10-07. Retrieved 2019-10-29.

- Rahim, Sameer. "Prospect world's top thinkers, 2019: the top ten". Retrieved 2019-09-22.

External links

- Official website

- Max Roser at the Oxford Martin School

- Our World in Data – one of the web publications of Max Roser

- Max Roser on Twitter

Work

- Memorizing these three statistics will help you understand the world – Gates Notes

- The map we need if we want to think about how global living conditions are changing – Our World in Data

- Income inequality: poverty falling faster than ever but the 1% are racing ahead – The Guardian

- ‘Seeing human lives in spreadsheets’ – Hans Rosling (1948–2017) – British Medical Journal (BMJ) – Opinion; February 2017

- Why do we not hear the good news? – Washington Post; December 2016.

- Inequality is a Choice – in Nuffield College Magazine, Issue 18. An edition in the memory of Tony Atkinson.

- The short history of global living conditions and why it matters that we know it – Our World in Data