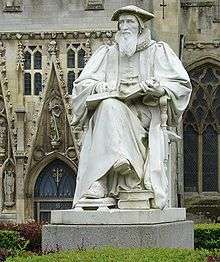

Matthew Parker

Matthew Parker (6 August 1504 – 17 May 1575) was an English bishop. He was the Archbishop of Canterbury in the Church of England from 1559 until his death in 1575. He was also an influential theologian and arguably the co-founder (with Thomas Cranmer and Richard Hooker) of a distinctive tradition of Anglican theological thought.

Matthew Parker | |

|---|---|

| Archbishop of Canterbury | |

| |

| Church | Church of England |

| Diocese | Canterbury |

| Installed | 19 December 1559 |

| Term ended | 17 May 1575 |

| Predecessor | Reginald Pole |

| Successor | Edmund Grindal |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 15 June 1527 |

| Consecration | 17 December 1559 by William Barlow |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 6 August 1504 Norwich, Kingdom of England |

| Died | 17 May 1575 (aged 70) Lambeth, Kingdom of England |

| Buried | Lambeth Chapel |

| Nationality | English |

| Denomination | Anglicanism |

Ordination history of Matthew Parker | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Source(s): [1] | |||||||||||||||||

Parker was one of the primary architects of the Thirty-nine Articles, the defining statements of Anglican doctrine. The Parker collection of early English manuscripts, including the book of St Augustine Gospels and "Version A" of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, was created as part of his efforts to demonstrate that the English Church was historically independent from Rome, creating one of the world's most important collections of ancient manuscripts. Along with Lawrence Nowell, Parker's work concerning the Old English literature laid the foundation for Anglo-Saxon studies.

Early years

The eldest son of William Parker, he was born in Norwich in St Saviour's parish. His mother's maiden name was Alice Monins and she may have been related by marriage to Thomas Cranmer. When William Parker died, in about 1516, his widow married John Baker. Parker was sent in 1522 to Corpus Christi College, Cambridge,[2] and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1525. He was ordained deacon on 20 April 1527 and priest on 15 June the same year. In September 1527 he was elected a fellow of Corpus Christi and began his Master of Arts degree in 1528. He was one of the Cambridge scholars whom Thomas Wolsey wished to transplant to his newly-founded Cardinal College at Oxford. Parker, like Cranmer, declined Wolsey's invitation. He had come under the influence of the Cambridge reformers, and after Anne Boleyn's recognition as queen he was made her chaplain. Through her, he was appointed dean of the college of secular canons at Stoke-by-Clare in Suffolk in 1535. Hugh Latimer wrote to him in that year urging him not to fall short of the expectations which had been formed of his ability. Shortly before Anne Boleyn's death in 1536, she commended to his care her daughter Elizabeth.[3] In 1537 he was appointed chaplain to King Henry VIII. In 1538 he was threatened with prosecution, but Richard Yngworth, the Bishop of Dover, reported to Thomas Cromwell that Parker "hath ever been of a good judgment and set forth the Word of God after a good manner. For this he suffers some grudge." He graduated Doctor of Divinity in that year, and in 1541 was appointed to the second prebend in the reconstituted cathedral church of Ely. In 1544, on Henry VIII's recommendation, he was elected master of Corpus Christi College, and in 1545 vice-chancellor of the university. He got into some trouble with the chancellor, Stephen Gardiner, over a ribald play, Pammachius, performed by the students, which derided the old ecclesiastical system.

Rise to power

On the passing of the Act of Parliament in 1545 enabling the king to dissolve chantries and colleges, Parker was appointed one of the commissioners for Cambridge, and their report may have saved its colleges from destruction. Stoke, however, was dissolved in the following reign, and Parker received a generous pension. He took advantage of the new reign to marry in June 1547, before clerical marriages were legalised by Parliament and Convocation, Margaret, daughter of Robert Harlestone, a Norfolk squire. They had initially planned to marry since about 1540 but had waited until it was not a felony for priests to marry.[4] The marriage was a happy one, although Queen Elizabeth's dislike of Margaret was later to cause Parker much distress. During Kett's Rebellion, he preached at the rebels' camp on Mousehold Hill near Norwich, without much effect, and later encouraged his secretary, Alexander Neville, to write his history of the rising.

Parker's association with Protestantism advanced with the times, and he received higher promotion under John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland, than under the moderate Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset. At Cambridge, he was a friend of Martin Bucer and preached Bucer's funeral sermon in 1551. In 1552 he was promoted to the rich deanery of Lincoln, and in July 1553 he supped with Northumberland at Cambridge, when the duke marched north on his hopeless campaign against the accession of Mary Tudor. As a supporter of Northumberland and a married man, under the new regime Parker was deprived of his deanery, his mastership of Corpus Christi and his other preferments. However, he survived Mary's reign without leaving the country – a fact that would not have endeared him to the more ardent Protestants who went into exile and idealised those who were martyred by Queen Mary. Parker respected authority, and when his time came he could consistently impose authority on others. He was not eager to assume this task, and made great efforts to avoid promotion to the archbishopric of Canterbury, which Elizabeth designed for him as soon as she had succeeded to the throne.

Archbishop of Canterbury (1559–1575)

Elizabeth wanted a moderate man, so she chose Parker. There was also an emotional attachment. Parker had been the favourite chaplain of Elizabeth's mother, Anne Boleyn. Before Anne was arrested in 1536 she had entrusted Elizabeth's spiritual well-being to Parker. A few days afterwards Anne was executed following charges of adultery, incest and treason. Parker also possessed all the qualifications Elizabeth expected from an archbishop, except celibacy. Elizabeth had a strong prejudice against married clergy, and in addition she seems to have disliked Margaret Parker personally, often treating her so rudely that her husband was "in horror to hear it".[5] After a visit to Lambeth, the Queen duly thanked her hostess but maliciously asked how she should address her, "For Madam I may not call you, mistress I should be ashamed to call you."[6]

Parker was elected on 1 August 1559 but, given the turbulence and executions that had preceded Elizabeth's accession, it was difficult to find the requisite four bishops willing and qualified to consecrate him, and not until 19 December was the ceremony performed at Lambeth by William Barlow, formerly Bishop of Bath and Wells, John Scory, formerly Bishop of Chichester, Miles Coverdale, formerly Bishop of Exeter, and John Hodgkins, Bishop of Bedford. The allegation of an indecent consecration at the Nag's Head public house seems first to have been made by a Jesuit, Christopher Holywood, in 1604, and has since been discredited. Parker's consecration was, however, legally valid only by the plenitude of the Royal Supremacy approved by the Commons and reluctantly by a vote of the Lords 21-18; the Edwardine Ordinal, which was used, had been repealed by Mary Tudor and not re-enacted by the parliament of 1559.

Parker mistrusted popular enthusiasm, and he wrote in horror of the idea that "the people" should be the reformers of the church. He was convinced that if ever Protestantism was to be firmly established in England at all, some definite ecclesiastical forms and methods must be sanctioned to secure the triumph of order over anarchy, and he vigorously set about the repression of what he thought a mutinous individualism incompatible with a catholic spirit.[7]

He was not an inspiring leader and no dogma or prayer book is associated with his name. However, the English composer Thomas Tallis contributed Nine Tunes for Archbishop Parker's Psalter which bears his name. The 55 volumes published by the Parker Society include only one by its eponymous hero, and that is a volume of correspondence. He was a disciplinarian, a scholar, a modest and moderate man of genuine piety and irreproachable morals.

Probably his most famous saying, prompted by the arrival of Mary Queen of Scots in England, was "I fear our good Queen has the wolf by the ears."[8]

Dispute about the validity of his consecration in 1559

Parker's consecration gave rise to a dispute, which continues to this day, in regard to its sacramental validity from the perspective of the Roman Catholic Church. This eventually led to the condemnation of Anglican orders as "absolutely null and utterly void" by a papal commission in 1896. The commission could not dispute that a consecration had taken place which met all the legal and liturgical requirement or deny that a "manual" succession, that is, the consecration by the laying on of hands and prayer had not taken place. Rather the Pope asserted in the condemnation that the "defect of form and intent" rendered the rite insufficient to make a bishop in the apostolic succession (according the Roman understanding of the minima for validity).[9] Specifically the English rite was considered to be defective in "form", i.e. in the words of the rite which did not mention the "intention" to create a sacrificing bishop considered to be a priest in a higher degree, and the absence of a certain "matter" such as the handing of the chalice and paten to the ordinand to symbolise the power to offer sacrifice.[10]

The Church of England archbishops of Canterbury and York rejected the Roman Pontiff's arguments in Saepius Officio in 1897.[11] This rebuttal was written to demonstrate the sufficiency of the form and intention used in the Anglican Ordinal: they archbishops wrote that in the preface to Ordinal the intention clearly is stated to continue the existing holy orders as received. They stated that even if Parker's consecrators had private doubts or lacked intention to do what the rites of ordination clearly stated, it counted for nought, since the words and actions of a rite (the formularies) performed on behalf of the church by the ministers of the sacrament, and not the opinions, however erroneous or correct, or inner states of mind or moral condition of the actors who carry them out, is the sole determinant. This view is also held by the Roman Catholic Church (and others) with few exceptions since the 3rd century. Likewise, according to the archbishops, the required references to the sacrificial priesthood never existed in any ancient Catholic ordination liturgies prior to the 9th century nor in certain current Eastern-rite ordination liturgies that the Roman Catholic Church considers valid nor in Orthodoxy. Also the archbishops argued that a particular formula in this respect as a sine qua non made no difference to the substance or validity of the act since the only two components that all ordination rites had in common were prayer and the laying on of hands, and in this regard, the words in the Anglican rite itself gave sufficient evidence as to the intent of the participants as stated in the preface, words and action of the rite. They pointed out that the only fixed and sure sacramental formulary is the baptismal rite.[12] They argued that it was not necessary to consecrate a bishop as a "sacrificing priest" since he already was one by virtue of being a priest, except in ordinations per saltim, i.e. from deacon to bishop when the person was made priest and bishop at once, a practice discontinued and forbidden.[13] They also pointed out that none of the priests ordained with the English Ordinal were re-ordained as a requirement by Queen Mary - some did so voluntarily and some were re-anointed, a practice common at the time.[14] On the contrary the Queen, unhappy about by married clergy, ordered all of them, estimated at 15% of the total at the beginning of her reign in 1553, to put their wives away.[15] Parker was ordained in 1527 in the Latin Rite and before the break with Rome. As such according to this rite he was a "sacrificing priest" to which nothing more could be added by being consecrated a bishop. The orders of the Church of Ireland were also condemned as part of the wider denunciation of Anglican orders.

In regard to the legal and canonical requirements the government was at pains to see all were met for the consecration. None of the 18 Marian bishops would agree to consecrate Parker. Not only were the opposed to the changes the bishops had been excluded from decision-making regarding changes in liturgy and doctrine. The reforms were approved by the Commons and narrowly by the Lords 21-18 after pressure was brought to bear on them; concessions were made in a more Catholic tone in eucharistic doctrine, and allowance made for the use of Mass vestments and other traditional clerical dress in use in the second year of the reign of Edward VI, i.e. January 1548 to 49, when the Latin Rite was still the legal form of worship (the 'Ornaments Rubric' in the 1559 Prayer Book seems to refer to the allowance as set forth in the 1549 BCP).[16]

The government recruited four bishops who had been retired by Queen Mary or gone into exile. Two of the four, William Barlow and John Hodgkins had in Rome's view valid orders, since, having been made bishops in 1536 and 1537 with the Roman Pontifical in the Latin Rite, their consecrations met the criteria according to the definition stated in Apostolicae Curae. John Scory and Miles Coverdale, the other two consecrators, were consecrated with the English Ordinal of 1550 on the same day in 1551 by Cranmer, Hodgkins and Ridley who were consecrated with the Latin Rite in 1532, 1537 and 1547 respectively.[17] This ordinal was considered defective in form and intention. All four of Parker's consecrators were consecrated by bishops who themselves had been consecrated with the Roman Pontifical in the Church of England which at the time was in schism from Rome. Even though two of the consecrators had orders recognised as validity by Rome the consecration was considered to be "null and void" by Rome because the ordinal used was judged to be defective in matter, form and intention.

In the first year of his archepiscopate Parker participated in the consecration of 11 new bishops and confirmed two who had been ordained in previous reigns.[18]

Later years

Parker avoided involvement in secular politics and was never admitted to Elizabeth's Privy Council. Ecclesiastical politics gave him considerable trouble. Some of the evangelical reformers wanted liturgical changes and at least the option not to wear certain clerical vestments, if not their complete prohibition. Early presbyterians wanted no bishops, and the conservatives opposed all these changes, often preferring to move in the opposite direction toward the practices of the Henrician church. The queen herself begrudged episcopal privilege until she eventually recognised it as one of the chief bulwarks of the royal supremacy. To Parker's consternation, the queen refused to add her imprimatur to his attempts to secure conformity, though she insisted that he achieve this goal. Thus Parker was left to stem the rising tide of Puritan feeling with little support from parliament, convocation or the Crown.

The bishops' Interpretations and Further Considerations, issued in 1560, tolerated a lower vestments standard than was prescribed by the rubric of 1559, but it fell short of the desires of the anti-vestment clergy such as Coverdale (one of the bishops who had consecrated Parker) who made a public display of their nonconformity in London.

The Book of Advertisements, which Parker published in 1566 to check the anti-vestments faction, had to appear without specific royal sanction; and the Reformatio legum ecclesiasticarum, which John Foxe published with Parker's approval, received neither royal, parliamentary or synodical authorisation. Parliament even contested the claim of the bishops to determine matters of faith. "Surely", said Parker to Peter Wentworth, "you will refer yourselves wholly to us therein." "No, by the faith I bear to God", retorted Wentworth, "we will pass nothing before we understand what it is; for that were but to make you popes. Make you popes who list, for we will make you none."

Disputes about vestments had expanded into a controversy over the whole field of church government and authority. Parker died on 17 May 1575, lamenting that Puritan ideas of "governance" would "in conclusion undo the queen and all others that depended upon her". By his personal conduct, he had set an ideal example for Anglican priests.[19]

He is buried in the chapel of Lambeth Palace.[20] Matthew Parker Street, near Westminster Abbey, is named after him.[21]

Scholarship

Parker's historical research was exemplified in his De antiquitate Britannicæ ecclesiae, and his editions of Asser, Matthew Paris (1571), Thomas Walsingham, and the compiler known as Matthew of Westminster (1571). De antiquitate Britannicæ ecclesiæ was probably printed at Lambeth in 1572, where the archbishop is said to have had an establishment of printers, engravers, and illuminators.[7]

Parker gave the English people the Bishops' Bible, which was undertaken at his request, prepared under his supervision, and published at his expense in 1572. Much of his time and labour from 1563 to 1568 was given to this work. He had also the principal share in drawing up the Book of Common Prayer, for which his skill in ancient liturgies peculiarly fitted him. His liturgical skill was also shown in his version of the psalter.[7] It was under his presidency that the Thirty-nine Articles were finally reviewed and subscribed by the clergy (1562).

Parker published in 1567 an old Saxon Homily on the Sacrament, by Ælfric of Eynsham. He published A Testimonie of Antiquitie Showing the Ancient Fayth in the Church of England Touching the Sacrament of the Body and Bloude of the Lord to prove that transubstantiation was not the doctrine of the ancient English Church.[7] Parker collaborated with his secretary John Joscelyn in his manuscript studies.

Manuscript collection

Parker left a priceless collection of manuscripts, largely collected from former monastic libraries, to his college at Cambridge. The Parker Library at Corpus Christi bears his name and houses most of his collection, with some volumes in the Cambridge University Library. The Parker Library on the Web project has made digital images of all of these manuscripts available online.

"Nosey Parker"

Parker's inquisitiveness about church matters is sometimes said to have led to his being called "nosey Parker" and this to have been the source of the common English term describing someone who pokes their nose into other people's business.[22] This has, however, no basis in fact.[23]

Notes

- The Apostolical Succession of the English Clergy Traced from the Earliest Times, And, in the Four Dioceses of Canterbury, London, Norwich, and Ely, Continued to the Year M.DCCC.LXII. p. 22 (Google Books)

- "Parker, Matthew (PRKR521M)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

-

- Nancy Balser Bjorklund, "A Godly Wife is an Helper: Matthew Parker and the Defense of Clerical Marriage", Sixteenth Century Journal Vol. 34, no. 2 (summer 2003) p. 350.

- Alison Weir, Elizabeth the Queen, Pimlico edition, 1999, p. 57.

- Lacey Baldwin Smith, The Elizabethan World, Houghton Mifflin Boston, 1967, p. 73.

- One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- Weir p. 195.

- O'Riordan M., "Apostolicae Curae", Catholic Encyclopedia, 1913, pp. 644-45.

- This is summed up as what effects a sacrament is the intention of administering that sacrament and the rite used according to that intention.O'Riordan 1907, p. 645

- Temple, Frederick; Maclagan, William (1897). Answer of the Archbishops of England to the Apostolic Letter of Pope Leo XIII on English Ordinations. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. Retrieved 19 March 2018

- Saepius Officio, IX; arguments based on Saepius Officio reviewed by The Reverend William J. Alberts, The Validity of Anglican Orders, National Guild of Churchmen, Holy Cross Magazine, West Park, NY

- Saepius Officio, XIII.

- Saepius Officio, VI.

- Christopher Haigh, The Tudor Revolutions, Religion, Politics, Society under the Tudors, 1991 pp. 226-227. ISBN 978-0-19-822162-3

- John H. R. Moorman, The Anglican Spiritual Tradition, 1983, p. 61 ISBN 0-87243-125-8; Diarmid MacCullough, The Later Reformation in England, 1547-1603, 1990 p. 26 ISBN 0-333-69331-0; Christopher Haigh, English Reformations, Religion, Politics and Society under the Tudors, 1993 pp. 240-242 ISBN 978-0-19-822162-3

- Project Canterbury, Supplementary Appendix A, Notes on the Consecration of Archbishop Parker, by Rev. Henry Barker, 2000; and the Register of the Diocese of Rochester on Ridley

- Project Canterbury, Supplementary Appendix A, Notes on the Consecration of Archbishop Parker, by Rev. Henry Barker, 2000

- Chisholm (1911)

- Archbishop of Canterbury's website

- Fairfield, S. The Streets of London – A dictionary of the names and their origins, p209

- Wallechinsky, David (2009). The Book of Lists. USA: Canongate Books. p. 480. ISBN 978-1847676672.

- The Phrase Finder: "Was the first Nosy Parker a real person and, if so, who? We don't know." Cf. also Oxford English Dictionary s.v. nosy parker (entry updated 2003): "Apparently < nosy adj. + the surname Parker. Compare (especially earlier) allusive use as a proper name, apparently with reference to a (probably fictitious) individual taken as the type of someone inquisitive or prying."

References

- Graham, Timothy and Andrew G. Watson (1998) The Recovery of the Past in Early Elizabethan England: Documents by John Bale and John Joscelyn from the Circle of Matthew Parker (Cambridge Bibliographical Society Monograph 13). Cambridge: Cambridge Bibliographical Society

- John Strype, Life of Parker, originally published in 1711, and re-edited for the Clarendon Press in 1821 (3 vols.), is the principal source for Parker's life.

- This work can be found online here: Volume I, Volume II, Volume III

- Archbishop Parker by W. P.M. Kennedy (1908, reprint by BiblioBazaar LLC, 2008) full text online at google.com

- J. Bass Mullinger's scholarly life in the Dictionary of National Biography

- Walter Frere's volume in Stephens and Hunt's Church History

- Strype's Works (General Index)

- Gough's Index to Parker Soc. Publ.

- Fuller, Gilbert Burnet, Collier and Richard Watson Dixon's Histories of the Church

- Henry Norbert Birt, The Elizabethan Religious Settlement

- Henry Gee, The Elizabethan clergy and the Settlement of religion, 1558–1564 (1898)

- James Anthony Froude, History of England

- vol. vi. in Longman's Political History.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Matthew Parker, "De antiquitate Britannicae Ecclesiae", binding for Queen Elizabeth I

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Matthew Parker. |

- Treasure 2 at the National Library of UK displayed via The European Library

- Parker Library on the Web

| Church of England titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Reginald Pole |

Archbishop of Canterbury 1559–1575 |

Succeeded by Edmund Grindal |

| Academic offices | ||

| Preceded by John Madew |

Vice-Chancellor of the University of Cambridge 1545 |

Succeeded by John Madew |

| Preceded by William Bill |

Vice-Chancellor of the University of Cambridge 1548 |

Succeeded by Walter Haddon |

| Preceded by William Sowode |

Master of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge 1544–1553 |

Succeeded by Lawrence Moptyd |