Maria Cunitz

Maria Cunitz or Maria Cunitia[1][2] (other versions of surname include: Cunicia, Cunitzin,[3] Kunic, Cunitiae, Kunicia, Kunicka[4]) (Wołów, Silesia, 1610 – Byczyna, Silesia, August 22, 1664) was an accomplished Silesian astronomer, and the most notable female astronomer of the early modern era. She authored a book Urania propitia, in which she provided new tables, new ephemera, and a simpler working solution to Kepler's Area Law for determining the position of a planet on its elliptical path. The Cunitz crater on Venus is named after her. The minor planet 12624 Mariacunitia is named in her honour.[5]

Maria Cunitz or Maria Cunitia | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1610 Wohlau, Silesia |

| Died | August 22, 1664 Pitschen, Silesia |

| Nationality | German or Polish |

| Education | Tutored by Dr. Elias von Löwen |

| Known for | Urania propitia |

| Spouse(s) | David von Gerstmann (m. 1623) Dr. Elias von Löwen (m. 1630) |

| Children | Elias Theodor, Anton Heinrich and Franz Ludwig |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Astronomy, Mathematics |

Life

Maria Cunitz was born in Wohlau (now Wołów, Poland), as the eldest daughter of a Baltic German, Heinrich Cunitz,[6][7] a physician and landowner who had lived in Schweidnitz for most of his life, and Maria Scholtz from Liegnitz,[8][9] daughter of German scientist Anton von Scholtz[10] (1560–1622), a mathematician and counselor to Duke Joachim Frederick of Liegnitz. The family eventually moved to Schweidnitz in Lower Silesia (today Świdnica, Poland). At an early age Maria married (in 1623) the lawyer David von Gerstmann. After his death in 1626, she married (in 1630) Elias von Löwen,[11] also from Silesia.[12] Elias von Lowen was also known as Elie de Loewen was a physician at Pitschen and studied astronomy.[3] Elias von Lowen was Maria's tutor[13] and encouraged Maria to pursue astronomy before their marriage in 1630.[3] Together they made observation of Venus on December 14, 1627 and Jupiter on April 1628.[3] Other areas of study included medicine, poetry, painting, music, mathematics, ancient languages, and history.[14] Elias and Maria had three sons: Elias Theodor, Anton Heinrich and Franz Ludwig.[3]

During the Thirty Year's War from 1618 to 1648 Maria and Elias von Löwen[15] stayed in the Cistercians convent of Olobok, Poland.[3] While at the cloister in Poland, Cunitz expanded her astronomical tables to include all of the planets at any moment in time.[15] At the end of the Thirty Year's War the couple returned to their home at Pitschen in Silesia.[3] In 1650, Maria privately published of her own expense Urania propitia in German and Latin as a dedication to Emperor Ferdinand III.[3] Urania propitia was a simplification of Kepler's Rudolphine Tables due to their difficulty of producing calculations and applications, because the use of logarithms.[16] In the evening of May 25, 1656 in Pitschen, Silesia a large fire destroyed most of the homes in the city, including Maria's home, Maria lost astronomical instruments and Elias lost medical instruments.[3] The fire consumed Maria's books, letters, and more than 200 records of astronomical observations.[3] Maria became a widow again in 1661, and died at Pitzen on August 22, 1664.[11][17]

The year of Maria's birth is uncertain. No birth, baptism or similar documents have ever been located. The year was speculated about in the first major German-language publication about Maria Cunitz of 1798.[18] Paul Knötel appears to be the first to give the year 1604 as the year of Maria's birth.[19] This date seemed to make sense since her parents married the previous year. Other authors later appear to have repeated the same year. The proof that Maria was actually born in 1610 is furnished by an anthology with congratulation poems on her first wedding, in connection with a letter of Elias A Leonibus to Johannes Hevelius from the year 1651, noted by Ingrid Guentherodt.[20][21] Full details concerning the family of Maria Cunitz have been published by KIaus Liwowsky.[22]

Accomplishments

The publication of the book Urania propitia (Olse,[23] Silesia, 1650) gained Cunitz a European reputation. Cunitz's husband, Elias von Löwen, wrote a preface in Urania propitia to cast out any rumors that it was Elias von Löwen that computed the tables[24] and to show support for his wife.[25] Urania propitia was written in Latin and German to further accessibility in the simplification of Kepler's Rudolphine tables (1627)[13] by correcting several of Kepler's errors.[26] Maria's work allowed for simpler algorithms leading to fewer calculations and errors, but Maria created new errors by omitting some of the small coefficients in her formulas.[26] Urania propitia provided new tables, new ephemera, and a more elegant solution to Kepler's Problem, which is to determine the position of a planet in its orbit as a function of time.[15] Today, her book is also credited for its contribution to the development of the German scientific language.[27] Due to her many talents and accomplishments, Cunitz was called the "Silesian Pallas" by J.B. Delambre, who also compared her to Hypatia of Alexandria during his study of history in astronomy.[26]

In 1727 the book Schlesiens Hoch- und Wohlgelehrtes Frauenzimmer, nebst unterschiedenen Poetinnen..., Johan Caspar Eberti wrote[28] that

(Maria) Cunicia or Cunitzin was the daughter of the famous Henrici Cunitii. She was a well-educated woman, like a queen among the Silesian womanhood. She was able to converse in seven languages, German, Italian, French, Polish, Latin, Greek and Hebrew, was an experienced musician and an accomplished painter. She was a dedicated astrologist and especially enjoyed astronomical problems.

Urania propitia was privately published and as of 2016 there are nine physical copies in the world[3] along with multiple online copies.[29] Physical copies can be found in the Library of the Astronomical Observatory of Paris,[3] Library of the University of Florida,[3] in the exhibit of Galileo and Kepler at the University Libraries of Norman, Oklahoma[30], and Bloomington Lilly Library of Indiana University[31]. Prior to June 10, 2004 the first edition of Urania propitia was located at The Library of The Earls of Macclesfield in the Shirburn Castle: Part 2 Science A-C section.[32] The book was sold at the Sotheby's auction house for $19,827 USD.[32]

Nationality

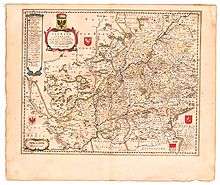

Maria Cunitz is usually characterized as Silesian, for example in the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition of 1911.[11] She was born and spent most of her life in the Holy Roman Empire, which included non-German minorities, ruled by the Austrian Habsburg Monarchy. The fragment of Silesia in which Maria lived was part of Bohemia before 990,[33] the united Poland between 990 [33][34] and 1202[35] and part of Bohemia between 1038 and 1050.[36] In 1202 the Polish seniorate was abolished and all Polish Duchies, including Silesia, became independent,[35] although four Silesian dukes of the 13th century were rulers of Kraków and held the title Duke of Poland.[35][37] In 1331 the region again became part of Bohemia.[38] In 1742 it became part of Prussia and in 1871 the German Empire. About three centuries after Maria's lifetime it was reassigned to Poland after World War II.

During Maria's lifetime, nationality did not play as significant a role in determining person's identity as it does today.[39][40] Nevertheless, multiple later sources felt the need to assign to Maria Cunitz a nationality relevant to their own time. She has mostly been described as German, for example in the Biographical Dictionary of Woman in Science.[41] She published in German. She has been also described as Polish[4][42][43] and some[4] consider her to be the first Polish woman astronomer. Cunitz spoke not only German and Polish but also French, Greek, Italian, Latin and Hebrew.[44]

References

- Cunitz, Maria. "Urania propitia, sive Tabulæ Astronomicæ mirè faciles, vim hypothesium physicarum à Kepplero proditarum complexae; facillimo calculandi compendio, sine ullâ logarithmorum mentione paenomenis satisfacientes; Quarum usum pro tempore praesente, exacto et futuro succincte praescriptum cum artis cultoribus communicat Maria Cunitia. Das ist: Newe und Langgewünschete, leichte Astronomische Tabelln, etc.", Oels, Silesia,1650.

- "Katalog z wystawy Astronom Maria Kunic". www.olesnica.org.

- Bernardi, Gabriella (2016). The Unforgotten Sisters : female astronomers and scientists before Caroline Herschel. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 61–66. ISBN 978-3-319-26125-6. OCLC 944920062.

- Storm Dunlop, Michèle Gerbaldi, "Stargazers: the contribution of amateurs to astronomy", Springer-Verlag, 1988, pg. 40

- "Discovery Circumstances: Numbered Minor Planets (10001)-(15000)". Minor Planet Center.

- Allgemeines Schriftsteller- und Gelehrten-Lexikon der Provinzen Livland, Esthland und Kurland, Volume 1, J.F. Steffenhagen und Sohn, 1827

- Sigrid Dienel: Die Pestschrift des schlesischen Arztes Heinrich Cunitz (1580-1629) aus dem Jahr 1625: ein zeitgenössisches medizinisch-pharmazeutisches Dokument? : eine vergleichende Untersuchung mit Pestschriften aus dem 16. und 17. Jahrhundert, 2000

- Marilyn Bailey Ogilvie, The Biographical Dictionary of Women in Science: Pioneering Lives From Ancient Times to the Mid-20th Century, 2000, page 309.

- Name Lignitz on the map from that period File:Blaeu 1645 - Nova totius Germaniæ descriptio.jpg

- Johann Heinrich Zedler, Grosses vollständiges Universal-Lexicon Aller Wissenschafften und Künste, 68 Bände, Leipzig 1732–1754, hier: Band 35, Spalte 1618f.

- Chisholm 1911.

- Article „Löwen, Elias von“ in: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie, herausgegeben von der Historischen Kommission bei der Bayrischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Band 19 (1884), ab Seite 311, Digitale Volltext-Ausgabe in Wikisource, URL: http://de.wikisource.org/w/index.php?title=ADB:L%C3%B6wen,_Elias_von&oldid=810951 (Version vom 21. August 2009, 02:44 Uhr UTC)

- Ogivie, Marilyn; Harvey, Joy (2000). The Biographical Dictionary of Women in Science. New York and London: Routledge. pp. 308–309.

- Ogilvie, Marilyn (1986). Women in Science. Massachusetts: the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. pp. 63–64. ISBN 0-262-15031-X.

- van Schurman, Anna Maria (1998). Whether a Christian Woman Should Be Educated and Other Writings from Her Intellectual Circle. University of Chicago Press. p. 217. ISBN 9780226849980.

- Rohrbach, Augusta (2014). Thinking Outside the Book. University of Massachusetts Press. p. 147. ISBN 9781625341259.

- Swerdlow, N.M. (2012). "Urania Propitia, Tabulae Rudophinae faciles redditae a Maria Cunitia Beneficent Urania, the Adaptation of the Rudolphine Tables by Maria Cunitz". In Buchwald, Jed Z. (ed.). A Master of Science History: Essays in Honor of Charles Coulston Gillispie. Springer. p. 119. ISBN 9789400726277.

- Johann Ephraim Scheibel: Nachrichten von der Frau von Lewen geb. Cunitzin. In: Astronomische Bibliographie, der 3. Abteilung, zweite Fortsetzung, Schriften aus dem siebzehnten Jahrhundert von 1631 bis 1650 aus der Reihe Einleitung zur mathematischen Bücherkenntnis. Nr. 20, Breslau 1798, pages 361-378.

- Paul Knötel: Maria Cunitia. In: Friedrich Andreae (Hrsg.): Schlesier des 17. bis 19. Jahrhunderts, Schlesische Lebensbilder. Nr. 3, Breslau 1928, pages 61-65.

- Ingrid Guentherodt: Maria Cunitia. Urania propitia; Intendiertes, erwartetes und tatsächliches Lesepublikum einer Astronomin des 17. Jh.. In: Daphnis. Zeitschrift für mittlere deutsche Literatur. Nr. 20, 1991, pages 311-353.

- Ingrid Guentherodt: Frühe Spuren von Maria Cunitia und Daniel Czepko in Schweidnitz 1623. In: Daphnis. Zeitschrift für mittlere deutsche Literatur. Nr. 20, 1991, pages 547-584.

- Liwowsky, Klaus. Einige Neuigkeiten uber die Familie der Schlesierin Maria Cunitz. Koblenz/Rhein, 2010.

- Name Olse as on Blaeu's 1645 map of Silesia File:Blaeu 1645 - Silesia Ducatus.jpg

- Schlager, Neil; Lauer, Josh (2001). "Maria Cunitz". Science and Its Times. 3: 1450 to 1699: 390 – via Gale.

- Rohrbach, Augusta (2014). Thinking Outside the Book. University of Massachusetts Press. p. 86.

- Bernardi, Gabriella (2016). The Unforgotten Sisters. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. pp. 61–66. ISBN 978-3-319-26125-6.

- Ingrid Güntherodt (Guentherodt), Maria Cunitz und Maria Sibylla Merian: Pionirinnen der Deutsches Wissenschaftssprache im 17. Jahrhundret, Zeitschrift für Germanistische Linguistik, Vol. 14, 1, pp. 23-49, DOI: 10.1515/zfgl.1986.14.1.23, Oct.2009.

- Johann Caspar Eberti. "Eröffnetes Cabinet dess gelehrten Frauen-Zimmers. Darinnen die berühmtesten dieses Geschlechtes." Iudicium, München 2004, ISBN 3-89129-998-2. (Repr. of Schlesiens Hoch- und Wohlgelehrtes Frauenzimmer, nebst unterschiedenen Poetinnen, so sich durch schöne und artige Poesien bey der curieusen Welt bekandt gemacht, etc, Breslau 1727), pages 25-28.

- Cunitz, Maria (1610-1664) (1650). "Urania propitia sive Tabulae Astronomicae mire faciles [...]" (in Polish). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "The Generous Muse of the Heavens". galileo. June 23, 2015. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- "IUCAT". Indiana University. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- "Cunitz (Cunitia), Maria (c. 1604-1664)". Sotheby's est. 1744. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- Handbuch der historischen Stätten: Schlesien, 2003, Hubert Weczerka, page XXXI, Stuttgart: Alfred Kröner Verlag, ISBN 3-520-31602-1

- Dehio - Handbuch der Kunstdenkmäler in Polen: Schlesien, Badstübner, Ernst; Dietmar Popp, Andrzej Tomaszewski, Dethard von Winterfeld, page 1, 2005, München, Deutscher Kunstverlag 2005, ISBN 3-422-03109-X

- Handbuch der historischen Stätten: Schlesien, 2003, Hubert Weczerka, page XXXV, Stuttgart: Alfred Kröner Verlag, ISBN 3-520-31602-1

- Handbuch der historischen Stätten: Schlesien, 2003, Hubert Weczerka, page XXXII + XXXIII, Stuttgart: Alfred Kröner Verlag, ISBN 3-520-31602-1

- (in English) Oskar Halecki, Antony Polonsky (1978). A history of Poland. Routledge. pp. :36–37. ISBN 0-7100-8647-4. Google Books

- Handbuch der historischen Stätten: Schlesien, 2003, Hubert Weczerka, page 128, Stuttgart: Alfred Kröner Verlag, ISBN 3-520-31602-1

- Smith, Anthony D. (1993). National Identity. Reno: University of Nevada Press. p. 72. ISBN 0-87417-204-7.

- "The Dynamics of the Policies of Ethnic Cleansing in Silesia in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries" by Tomasz Kamusella, Open Society Institute, Center for Publishing Development, Budapest, Hungary, 1999, "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 24, 2017. Retrieved February 24, 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Marilyn Bailey Ogilvie, Joy Dorothy Harvey, "The Biographical Dictionary of Women in Science: Pioneering Lives from Ancient Times to the Mid-20th Century", Routledge, 2000, pg. 309,

- Rayner-Canham, Marelene F.; Rayner-Canham, Marelene; Rayner-Canham, Geoffrey (April 5, 2018). "Women in Chemistry: Their Changing Roles from Alchemical Times to the Mid-twentieth Century". Chemical Heritage Foundation – via Google Books.

- "Cisterscian localisations - Cistercian Track in Poland". www.szlakcysterski.org. Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved August 10, 2009.

- "Bibliotheca Sacra". Dallas Theological Seminary. April 5, 2018 – via Google Books.

- Attribution

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maria Cunitz. |