Maracanã Stadium

The Maracanã (Portuguese: Estádio do Maracanã, standard Brazilian Portuguese: [esˈtadʒi.u du maɾakɐˈnɐ̃], local pronunciation: [iʃˈtadʒu du mɐˌɾakɐˈnɐ̃]), officially named the Estádio Jornalista Mário Filho (IPA: [iʃˈtadʒ(i)u ʒoʁnaˈliʃtɐ ˈmaɾi.u ˈfiʎu]), is a stadium in Rio de Janeiro. The stadium is part of a complex that includes an arena known by the name of Maracanãzinho, which means "The Little Maracanã" in Portuguese. Owned by the Rio de Janeiro state government, it is, as is the Maracanã neighborhood where it is located, named after the Rio Maracanã, a now canalized river in Rio de Janeiro.

Maracanã Stadium | |

Aerial view of the Maracanã complex in 2014, with the stadium visible at top and the Maracanãzinho at left

| |

| Former names | Estádio do Maracanã (1950–1966)[1] |

|---|---|

| Location | Maracanã, Rio de Janeiro |

| Coordinates | 22°54′43.80″S 43°13′48.59″W |

| Public transit | Maracanã Station |

| Owner | Rio de Janeiro State Government |

| Operator | Complexo Maracanã Entretenimento S.A. (Odebrecht, IMX, AEG) |

| Capacity | 78,838[2] |

| Record attendance | 199,854 (16 July 1950) |

| Field size | 105 m × 68 m (344 ft × 223 ft) |

| Surface | Grass |

| Construction | |

| Broke ground | 2 August 1948 |

| Opened | 16 June 1950 |

| Renovated | 2000, 2006, 2013 |

| Architect | Waldir Ramos, Raphael Galvão, Miguel Feldman, Oscar Valdetaro, Pedro Paulo B. Bastos, Orlando Azevedo, Antônio Dias Carneiro |

| Tenants | |

| Clube de Regatas do Flamengo Fluminense FC Brazil national football team (selected matches) | |

The stadium was opened in 1950 to host the FIFA World Cup, in which Brazil was beaten, 2–1, by Uruguay in the deciding game, in front of 199,854 spectators on 16 July 1950.[3] The venue has seen attendances of 150,000 or more at 26 occasions, the last being on 29 May 1983, as 155,253 spectators watched Flamengo beat Santos, 3–0. The stadium has seen crowds of more than 100,000 284 times.[3] But as terraced sections have been replaced with seats over time, and after the renovation for the 2014 FIFA World Cup, its original capacity has been reduced to the current 78,838, but it remains the largest stadium in Brazil. The stadium is mainly used for football matches between the major football clubs in Rio de Janeiro, including Flamengo, Fluminense, Botafogo, and Vasco da Gama. It has also hosted a number of concerts and other sporting events.

The total attendance at the last (and indeed decisive game, but not a final) game of the 1950 World Cup was 199,854, making it the world's largest stadium by capacity when it was inaugurated. After its 2010–2013 renovation, the rebuilt stadium currently seats 78,838 spectators, making it the largest stadium in Brazil and the second in South America after Estadio Monumental in Peru.[4] It was the main venue of the 2007 Pan American Games, hosting the football tournament and the opening and closing ceremonies. The Maracanã was partially rebuilt in preparation for the 2013 FIFA Confederations Cup, and the 2014 World Cup, for which it hosted several matches, including the final. It also served as the venue for the opening and closing ceremonies of the 2016 Summer Olympics and Paralympics, with the main track and field events taking place at the Estádio Olímpico.

Name

The official name of the stadium, Mário Filho, was given in honor of an old Pernambucan journalist, the brother of Nelson Rodrigues, who was a strong vocal supporter of the construction of the Maracanã.

The stadium's popular name is derived from the Maracanã River, whose point of origin is in the jungle-covered hills to the west, crossing various bairros (neighborhoods) of Rio's Zona Norte (North Zone), such as Tijuca and São Cristóvão, via a drainage canal which features sloping sides constructed of concrete. Upon flowing into the Canal do Mangue, it empties into Guanabara Bay. The name "Maracanã" derives from the indigenous Tupi–Guarani word for a type of parrot which inhabited the region. The stadium construction was prior to the formation of the later Maracanã neighborhood, that was once part of Tijuca.

The stadium of Red Star Belgrade, the Red Star Stadium, is popularly called Marakana in honor of the Brazilian stadium.

History

Construction

After winning the right to host the 1950 FIFA World Cup, the Brazilian government sought to build a new stadium for the tournament. The construction of Maracanã was criticized by Carlos Lacerda, then Congressman and political enemy of the mayor of the city, general Ângelo Mendes de Morais, for the expense and for the chosen location of the stadium, arguing that it should be built in the West Zone neighborhood of Jacarepaguá. At the time, a tennis stadium stood in the chosen area. Still it was supported by journalist Mário Filho, and Mendes de Morais was able to move the project forward. The competition for the design and construction was opened by the municipality of Rio de Janeiro in 1947, with the construction contract awarded to engineer Humberto Menescal, and the architectural contract awarded to seven Brazilian architects, Michael Feldman, Waldir Ramos, Raphael Galvão, Oscar Valdetaro, Orlando Azevedo, Pedro Paulo Bernardes Bastos, and Antônio Dias Carneiro.[5]

The first cornerstone was laid at the site of the stadium on 2 August 1948.[6] With the first World Cup game scheduled to be played on 24 June 1950, this left a little under two years to finish construction. However, work quickly fell behind schedule, prompting FIFA to send Dr. Ottorino Barassi, the head of the Italian FA, who had organized the 1934 World Cup, to help in Rio de Janeiro. A work force of 1,500 constructed the stadium, with an additional 2,000 working in the final months. Despite the stadium having come into use in 1950, the construction was only fully completed in 1965.

Opening and 1950 FIFA World Cup

The opening match of the stadium took place on 16 June 1950. Rio de Janeiro All-Stars beat São Paulo All-Stars 3–1; Didi became the player to score the first ever goal at the stadium. While the major part of the stadium was finished, it still looked like a construction site; it lacked toilet facilities and a press box. Brazilian officials claimed it could seat over 200,000 people, while the Guinness Book of World Records estimated it could seat 180,000 and other sources pegged capacity at 155,000. What is beyond dispute is that Maracanã overtook Hampden Park as the largest stadium in the world.[7] Despite the stadium's unfinished state, FIFA allowed matches to be played at the venue, and on 24 June 1950, the first World Cup match took place, with 81,000 spectators in attendance.

In that first match for which Maracanã had been built, Brazil beat Mexico with a final score 4–0, with Ademir becoming the first scorer of a competitive goal at the stadium with his 30th-minute strike. Ademir had two goals in total, plus one each from Baltasar and Jair. The match was refereed by Englishman George Reader. Five of Brazil's six games at the tournament were played at Maracanã (the exception being their 2–2 draw with Switzerland in São Paulo). Eventually, Brazil progressed to the final round, facing Uruguay in the match (part of a round-robin final phase) that turned out to be the tournament-deciding match on 16 July 1950. Brazil only needed a draw to finish as champion, but Uruguay won the game 2–1, shocking and silencing the massive crowd. This defeat on home soil instantly became a significant event in Brazilian history, being known popularly as the Maracanazo. The official attendance of the final game was 199,854, with the actual attendance estimated to be about 210,000.[8][9] In any case, it was the largest crowd ever to see a football game—a record that is highly unlikely to be threatened in an era when most international matches are played in all-seater stadiums. At the time of the World Cup, the stadium was mostly grandstands with no individual seats.

Stadium completion and post-World Cup years

Since the World Cup in 1950, Maracanã Stadium has mainly been used for club games involving four major football clubs in Rio— Vasco, Botafogo, Flamengo and Fluminense. The stadium has also hosted numerous domestic football cup finals, most notably the Copa do Brasil and the Campeonato Carioca. On 21 March 1954, a new official attendance record was set in the game between Brazil and Paraguay, after 183,513 spectators entered the stadium with a ticket and 194,603 (177,656 p.) in Fla-Flu (1963). In 1963, stadium authorities replaced the square goal posts with round ones, but it was still two years before the stadium would be fully completed. In 1965, 17 years after construction began, the stadium was finally finished. In September 1966, upon the death of Mário Rodrigues Filho, the Brazilian journalist, columnist, sports figure, and prominent campaigner who was largely responsible for the stadium originally being built, the administrators of the stadium renamed the stadium after him: Estádio Jornalista Mário Rodrigues Filho. However, the nickname of Maracanã has continued to be used as the common referent. In 1969, Pelé scored the 1,000th goal of his career at Maracanã, against CR Vasco da Gama in front of 65,157 spectators.[10]

In 1989 the stadium hosted the games of the final round of the Copa America; in the same year, Zico scored his final goal for Flamengo at the Maracanã, taking his goal tally at the stadium to 333, a record that still stood as of 2011. An upper stand in the stadium collapsed on 19 July 1992, in the second game of the finals of 1992 Campeonato Brasileiro Série A, between Botafogo and Flamengo, leading to the death of three spectators and injuring 50 others.[11] Following the disaster, the stadium's capacity was greatly reduced as it was converted to an all-seater stadium in the late 1990s. Meanwhile, the ground was classified as a national landmark in 1998, meaning that it could not be demolished. The stadium hosted the first ever FIFA Club World Cup final match between CR Vasco da Gama and Corinthians Paulista, which Corinthians won on penalties.

21st century, renovations and 2014 FIFA World Cup

.jpg)

Following its 50th anniversary in 2000, the stadium underwent renovations which would increase its full capacity to around 103,000. After years of planning and nine months of closure between 2005 and 2006, the stadium was reopened in January 2007 with an all-seated capacity of 87,000.

For the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympics and Paralympics, a major reconstruction project was initiated in 2010. The original seating bowl, with a two-tier configuration, was demolished, giving way to a new one-tier seating bowl.[12] The original stadium's roof in concrete was removed and replaced with a fiberglass tensioned membrane coated with polytetra-fluoroethylene. The new roof covers 95% of the seats inside the stadium, unlike the former design, where protection was only afforded to some seats in the upper ring and the bleachers above the gate access of each sector. The old boxes, which were installed at a level above the stands for the 2000 FIFA Club World Championship, were dismantled in the reconstruction process. The new seats are colored yellow, blue and white, which combined with the green of the match field, form the Brazilian national colors. In addition, the grayish tone has returned as the main façade color of the stadium.

On 30 May 2013, a friendly game between Brazil and England scheduled for 2 June was called off by a local judge because of safety concerns related to the stadium. The government of Rio de Janeiro appealed the decision[13] and the game went ahead as originally planned, the final score being a 2–2 draw.[13] This match marked the reopening of the new Maracanã.[12]

On 12 June 2014, the 2014 FIFA World Cup opened with Brazil defeating Croatia, 3–1, but that match was held in São Paulo. The first game of the World Cup to be held in Maracanã was a 2–1 victory by Argentina over Bosnia-Herzegovina on Sunday, 15 June 2014. Host Brazil ended up never playing a match in the Maracanã during the tournament, as they failed to reach the final after being eliminated in the semi-finals 7-1 by Germany. In the final, Germany defeated Argentina 1–0 in extra time.[14]

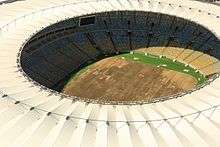

Disrepair after the 2016 Summer Olympics

The stadium lay dormant in the months after the 2016 Olympics and Paralympics, with photos surfacing in early 2017 of a dried-up playing field covered in brown spots and missing turf, ripped-out seats, and damage to windows and doors. A debt of R$3 million (US$939,937) to the local energy company led to power being shut off at Maracanã. At the heart of the issue was a legal wrangling between the stadium's owner, operator, and the organizing committee for the Rio Olympics over responsibility for maintaining the grounds. Maracanã SA, the operator, charges that the Olympic committee did not return the venue in an acceptable condition, while the committee says the things that they needed to fix should not keep Maracanã from operating.[15]

Within six months of the Olympics, daily tours of the stadium were halted due to vandalism at the stadium and violent robberies in the area. Items of value were looted from the stadium including fire extinguishers, televisions, and a bronze bust of journalist Mário Filho, for whom the stadium was named.[16][17]

New managers

On 5 April 2017, the French group Lagardère signed an agreement to administer the Maracanã. In total, Lagardère will invest more than R$500 million by the end of the concession, won by Odebrecht in 2013 and valid until 2048. The Folha de São Paulo newspaper informed that the group estimates that it will need to spend about R$15 million on emergency reforms at the stadium. In 2013, the former managers of Odebrecht together with AEG and IMX, a company owned by Brazilian billionaire Eike Batista, won the bid to manage the stadium for 35 years. The company was associated with Brazilian building company OAS and the Amsterdam Arena. At the time, Lagardère was in second place in the bidding.[18]

Non-football events

The fight Masahiko Kimura vs. Hélio Gracie between Japanese judoka Masahiko Kimura and Brazilian jiu-jitsu fighter Hélio Gracie was held at the Maracanã Stadium in Rio de Janeiro on October 23, 1951.

International sports competitions

- In 1980 and 1983, volleyball matches between Brazil and the USSR played at the ground. 95,000 people attended one of those volleyball matches, which became a world record.[19]

- The stadium hosted the opening and closing ceremonies of the XV Pan American Games.

- The stadium was selected to host the opening ceremony and closing ceremony of the 2016 Summer Olympics and the 2016 Summer Paralympics; it was the only Summer Olympics ceremonies venue never to have held a single athletics (track and field) event during its existence.

Music

- In 1991 Norwegian pop band, a-ha, broke the world record at that years Rock in Rio festival for a fee paying crowd. 198 000 people attended.[20][21][22]

- To celebrate the 30th anniversary of the stadium, on 16 January 1980, Frank Sinatra performed to a crowd of 175,000.[23][24]

- Tina Turner and Paul McCartney made the Guinness Book of World Records with performances at the stadium. Both concerts, in January 1988 (Break Every Rule Tour) and April 1990 (The Paul McCartney World Tour), respectively, attracted crowds of over 180,000 people.[23][25]

- On 18 June 1983, KISS performed for 137,000 fans at the stadium, which marks the record attendance for the band. This and two other stadium shows in Brazil would be the last time KISS would perform in their signature makeup until the reunion of the original lineup at their Alive/Worldwide Tour in 1996. Kiss' concert was the first major performance by an international rock band at Maracanã.

- From 18–27 January 1991, the stadium hosted the second edition of Rock in Rio, with Prince, Guns N' Roses, George Michael, INXS, a-ha and New Kids on the Block as headliners.

- American pop-singer Michael Jackson planned to perform here in October 1993 as part of his Dangerous World Tour, but concert was cancelled due to tour restructuring.

- Sting, Madonna and the Rolling Stones are the only international pop stars to have played dates at Maracanã on different occasions. Sting opened his ...Nothing Like the Sun world tour at the stadium on 20 November 1987. Approximately 20 years later, on 8 December 2007, he performed there again with The Police. Madonna played the venue on 6 November 1993, with the Girlie Show in front of 120,000 people, and then again 15 years later on 14 and 15 December 2008, as part of the Sticky & Sweet Tour, selling over 107,000 tickets. The 1995 edition of the Hollywood Rock festival consisted of two concerts by The Rolling Stones at the stadium, on February 2 and 4. The band performed at Maracanã again on February 20, 2016.

- On 25 January 2015, Foo Fighters played a concert at Maracanã Stadium during their Sonic Highways World Tour in front of 45,000 people. It was the first music concert held at the stadium since it was rebuilt. The group performed at the stadium again on February 25, 2018 during their Concrete and Gold Tour.

- Rush, Backstreet Boys, Pearl Jam and Coldplay also played the venue. Rush's concert in 2002 is documented on their live album and DVD Rush in Rio. Mexican pop group RBD also played its live DVD, Live in Rio. Brazilian artists also played at the stadium, like Ivete Sangalo, Sandy & Junior, Diante do Trono, Roberto Carlos and Los Hermanos.

- The stadium will host Ultra Brasil in October 2020.

Miscellaneous

- Pope John Paul II celebrated masses at the stadium in 1980, 1987 and 1997.[26][27]

- Billy Graham preached there in 1960 and in 1974

- Jimmy Swaggart preached there in 1987

Tournament results

1950 FIFA World Cup

| Date | Time (UTC-03) | Team #1 | Res. | Team #2 | Round | Attendance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 June 1950 | 15:00 | 4–0 | Group 1 | 82,000 | ||

| 25 June 1950 | 15:00 | 2–0 | Group 2 | 30,000 | ||

| 29 June 1950 | 15:00 | 2–0 | Group 2 | 16,000 | ||

| 1 July 1950 | 15:00 | 2–0 | Group 1 | 142,000 | ||

| 9 July 1950 | 15:00 | 7–1 | Final Round | 139,000 | ||

| 13 July 1950 | 15:00 | 6–1 | Final Round | 153,000 | ||

| 16 July 1950 | 15:00 | 2–1 | Final Round | 199,854 |

1989 Copa América

| Date | Time (UTC-03) | Team #1 | Res. | Team #2 | Round | Attendance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 July 1989 | 3–0 | Final Round | 100,135 | |||

| 12 July 1989 | 2–0 | Final Round | 100,135 | |||

| 14 July 1989 | 2–0 | Final Round | 53,909 | |||

| 14 July 1989 | 3–0 | Final Round | 53,909 | |||

| 16 July 1989 | 0–0 | Final Round | 148,068 | |||

| 16 July 1989 | 1–0 | Final Round | 148,068 |

2013 FIFA Confederations Cup

| Date | Time (UTC-03) | Team #1 | Res. | Team #2 | Round | Attendance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 June 2013 | 16:00 | 1–2 | Group A | 73,123 | ||

| 20 June 2013 | 16:00 | 10–0 | Group B | 71,806 | ||

| 30 June 2013 | 19:00 | 3–0 | Final | 73,531 |

2014 FIFA World Cup

| Date | Time (UTC-03) | Team #1 | Res. | Team #2 | Round | Attendance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 June 2014 | 19:00 | 2–1 | Group F | 74,393 | ||

| 18 June 2014 | 16:00 | 0–2 | Group B | 74,101 | ||

| 22 June 2014 | 13:00 | 1–0 | Group H | 73,819 | ||

| 25 June 2014 | 17:00 | 0–0 | Group E | 73,750 | ||

| 28 June 2014 | 17:00 | 2–0 | Round of 16 | 73,804 | ||

| 4 July 2014 | 13:00 | 0–1 | Quarter-finals | 73,965 | ||

| 13 July 2014 | 16:00 | 1–0 (a.e.t.) | Final | 74,738 |

2016 Summer Olympics

| Date | Time (UTC-03) | Team #1 | Res. | Team #2 | Round | Attendance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 August 2016 | 13:00 | 0–0 (a.e.t.) (3–4 pen.) | Women's Semifinals | 70,454 | ||

| 17 August 2016 | 13:00 | 6–0 | Men's Semifinals | 52,457 | ||

| 19 August 2016 | 17:30 | 1–2 | Women's Gold Medal Match | 52,432 | ||

| 20 August 2016 | 17:30 | 1–1 (a.e.t.) (5–4 pen.) | Men's Gold Medal Match | 63,707 |

2019 Copa América

| Date | Time (UTC-03) | Team #1 | Res. | Team #2 | Round | Attendance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 June 2019 | 16:00 | 2–2 | Group B | 19,196 | ||

| 18 June 2019 | 18:30 | 1–3 | Group A | 26,346 | ||

| 24 June 2019 | 20:00 | 0–1 | Group C | 57,442 | ||

| 28 June 2019 | 16:00 | 0–2 | Quarter-finals | 50,094 | ||

| 7 July 2019 | 17:00 | 3–1 | Final | 69,968 |

Further reading

- Gaffney, Christopher Thomas. Temples of the Earthbound Gods: Stadiums in the Cultural Landscape of Rio de Janeiro and Buenos Aires. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-292-72165-4

See also

References

- "Estádio Jornalista Mário Filho referred to as Maracanã".

- http://secure.rio2016.com/maracana/o-novo-estadio-do-maracana-tera-capacidade-para-78639-espectadores

- "Futebol Brasileiro 1950-1999 Best Attendances". rsssfbrasil.com. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- "Maracanã fica mais moderno sem abrir mão de sua história" (in Portuguese). Estado de S. Paulo. Archived from the original on 22 September 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- "El fútbol vuelve al histórico Maracanã tras nueve meses de espera". El País (in Spanish). 22 January 2006. Archived from the original on 9 January 2009. Retrieved 20 October 2008.

- "Soccer Hall: 1950 FIFA World Cup". soccerhall.org. Archived from the original on 30 March 2009. Retrieved 23 March 2007.

- "Sambafoot.com: Maracanã, the largest stadium of the world". Sambafoot.com. Retrieved 23 March 2007.

- "Futebol; the Brazilian way of life". Archived from the original on 17 March 2007. Retrieved 23 March 2007.

- "Sambafoot.com: Maracanã, the largest stadium of the world (part 2)". sambafoot.com. p. 2. Retrieved 23 March 2007.

- [Book Almanaque do Santos]

- "Sports Disasters". Retrieved 23 March 2007.

- says, Wojciech. "Maracana - Rio de Janeiro - The Stadium Guide". stadiumguide.com. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- "Brazil v England suspended over Maracanã safety concerns". BBC Sport. 30 May 2013. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- Fitzgerald, Daniel. "15 Biggest Stories of the 2014 FIFA World Cup". Bleacher Report. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- Flora Charner; Shasta Darlington. "How the Maracana became a 'ghost' stadium". CNN. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- CNN, Flora Charner and Shasta Darlington. "How the Maracanã became a 'ghost' stadium". CNN.

- sport, Guardian (9 February 2017). "Rio Olympic venues already falling into a state of disrepair". The Guardian.

- "Grupo francês acerta compra da gestão do Maracanã - 05/04/2017 - Esporte - Folha de S.Paulo". m.folha.uol.com.br. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- "95000 fans at volleyball match :: Volleybox.net". Retrieved 13 April 2019 – via volleybox.net.

- https://rockinrio.com/usa/great-artists-make-history-a-ha/

- A-ha

- http://www.discomania.gr/v2/artists.ownpdf?view=artist&id=12

- "A record 180,000 turn out for Tina". Chicago Sun-Times. 18 January 1988. Archived from the original on 16 December 2017. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- Russell, Alan (1 October 1986). Guinness Book of World Records 1987. Sterling. Retrieved 15 December 2017 – via Internet Archive.

Frank Sinatra 175,000 guinness.

- "Arts and Media/Music Feats & Facts/Solo Rock Show Crowd". archive.org. 25 May 2006. Archived from the original on 25 May 2006. Retrieved 9 December 2017.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- http://visit.rio/en/que_fazer/maracanastadium/

- https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/pt/travels/1997/documents/hf_jp-ii_spe_04101997_families.html

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Estádio do Maracanã. |

- Official website

- Maracanã - Estádio Jornalista Mário Filho, Rio De Janeiro - FIFA Profile

- Maracanã at StadiumDB.com

- Photo Gallery of Museum and Game @ The Rio de Janeiro Photo Guide

- RSSSF Best Attendances in Brazil