Mandar Syah

Sultan Mandar Syah (b. c. 1625-d. 3 January 1675) was the 11th Sultan of Ternate who reigned from 1648 to 1675. Like his predecessors he was heavily dependent on the Dutch East India Company (VOC), and was forced to comply to Dutch demands to extirpate spice trees in his domains, ensuring Dutch monopoly of the profitable spice trade. On the other hand, the Ternate-VOC alliance led to a large increase of Ternatan territory in the war with Makassar in 1667.

| Sultan Mandar Syah | |

|---|---|

| Sultan of Ternate | |

| Reign | 1648–1675 |

| Predecessor | Hamza |

| Successor | Sibori Amsterdam |

| Died | 3 January 1675 |

| Father | Mudafar Syah I |

| Religion | Islam |

Accession

Kaicili (prince) Tahubo, the later Mandar Syah, was only a few years old when his father Sultan Mudafar Syah I passed away in 1627. He had two older brothers, Kaicili Kalamata and Kaicili Manilha, and was therefore not a likely candidate for the Ternatan throne.[1] An older kinsman, Hamza ruled as Sultan from 1627 to 1648 when he passed away without sons. Now the grandees of the kingdom wanted Manilha to be their new ruler, while Muslim clerics preferred Kalamata. However, the VOC, whose influence in the affairs of Ternate was on the rise, insisted that the youngest brother Tahubo should be installed since he had been raised under the supervision of the Dutch governors in Ternate.[2] The Ternatan elite was less than pleased, and so Tahubo, who took the title Sultan Mandar Syah, was even more dependent on Dutch goodwill than his two predecessors. His Dutch leanings can be seen from the names that he gave a few of his sons: Prince Amsterdam, Prince Rotterdam.

The rebellion of Manilha

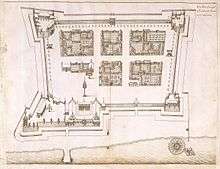

.jpg)

Dissatisfaction with Mandar Syah's dependence on the Company soon led to open opposition from the influential House of Fala Rahi and the various Bobatos (chiefs) of Ternate. In August 1650 they elected his brother Manilha, supposedly a mentally unstable person, as Sultan in opposition. They believed that Manilha would be more sensible to Ternatan community leaders. The attempt soon faltered, since the Dutch were not ready to abandon their candidate. Admiral Arnold de Vlamingh van Oudshoorn turned up in Maluku in 1651 and forced Manilha to yield. The other brother Kalamata, an able figure and an expert in Islamic law, continued to create trouble for the Dutch during the coming years and eventually fled to Ternate's political rival Makassar. Anti-Dutch opposition also spread to the Hoamoal Peninsula in West Ceram and the Muslim realm Hitu in Ambon, both of which were formally Ternatan dependencies. Admiral de Vlamingh van Oudshoorn, enjoined by Mandar Syah, spent several years suppressing the resistance, an extremely bloody affair that finally ensured total Dutch control over the clove-producing Ambon Quarter.[3]

Extirpation of clove trees

Apart from the rebellions, the selling of spices to merchants operating outside the VOC was a problem for the Dutch authorities, who deemed such practices "smuggling". The solution was to force the periphery areas in Maluku to stop producing spices. Here Mandar Syah was a useful tool to enforce Dutch spice monopoly. A treaty with the Sultan was signed on 31 July 1652. Mandar Syah agreed to allow the destruction of all clove trees in Ternate and the Ambon dependencies. In return, the Sultan received an annual sum (recognitiepenningen) of 12,000 rijksdaalders. Some of this money was to be allocated to the various Bobatos. In practice, this became a way for the Sultan to keep the Bobatos in check since those showing signs of disobedience had their subsidies withdrawn. This differed from the old system where the Bobatos kept incomes from the clove trade for the needs of their own community (soa).[4] Similar contracts were concluded with the other sultanates Bacan and Tidore.[5] The Company and the Sultans upheld the monopoly by means of regular expeditions, hongitochten, that cruised the islands and destroyed any spice tree that was found. Such hongitochten were conducted until the 19th century and gained notoriety for brutality.[6]

Political gains

The rise of the Makassar Kingdom in the first half of the 17th century had grave consequences for the Sultante of Ternate. Large areas such as Buton, Banggai, Tobungku, Menado, Sula and Buru fell away from Ternatan overlordship.[7] Here, the growing power of the VOC turned out to be advantageous. Ternate supported the VOC expedition to Makassar in 1667 with a small force. Makassar was crushed with the help of the Bugis leader Arung Palakka and forced to sign the Treaty of Bongaya in the same year. One of the stipulations was that Ternate regained its old vassals in Sulawesi and adjacent islands.[8] Another political rival, the Tidore Sultanate, left its traditional alliance with Spain and made contracts with the VOC in 1657 and 1667, which for the moment put an end to the long history of Ternatan-Tidorese rivalries and petty wars.[9]

The legacy of Sultan Mandar Syah was therefore ambivalent: on one hand close dependency on the VOC, but on the other hand a strengthening of the Sultan's own powers at the expense of officials and chiefs, and a dramatic increase in territory. These contradiction would lead to open anti-Dutch rebellion under his son Sibori Amsterdam who succeeded him in 1675.[10]

Family

Sultan Mandar Syah married the following wives and co-wives:[11]

- A daughter of Sultan Saidi of Tidore (possibly merely engaged)

- A princess of Buton

- Maya from Ternate, mother of Boki Mahir

- Lawa, mother of Amsterdam, Malayu, Mauludu and Sarabu

- Maryam from Sahu, mother of Rotterdam and Boki Gogugu

- Ainun, mother of Toloko

- A Makassarese woman, mother of Neman

- A Gorontalese woman, mother of Hukum and Diojo

His sons (Kaicili, princes) and daughters (Boki, princesses) were:[12]

- Boki Mahir Gammalamo

- Kaicili Sibori Amsterdam, Sultan of Ternate

- Kaicili Malayu

- Boki Mauludu

- Boki Sarabu

- Kaicili Rotterdam alias Yena

- Boki Gogugu

- Kaicili Toloko, Sultan of Ternate

- Kaicili Neman

- Kaicili Hukum

- Boki Diojo

- Boki Timonga

- Boki Tabilo

See also

- List of rulers of Maluku

- Sultanate of Ternate

- Tidore Sultanate

References

- C.F. van Fraassen (1987) Ternate, de Molukken en de Indonesische Archipel. Leiden: Rijksmuseum te Leiden, Vol. II, p. 20.

- P.A. Tiele (1895) Bouwstoffen voor de geschiedenis der Nederlanders in den Maleischen Archipel, Vol. III. 's Gravenhage: Nijhoff, p. xxxvii.

- Leonard Andaya (1993) The world of Maluku. Honolulu: Hawai'i University Press, p. 162-4.

- Leonard Andaya (1993), p. 167-8.

- F.C. van Fraassen (1987), Vol. I, p. 52.

- Willard A. Hanna & Des Alwi (1990) Turbulent times past in Ternate and Tidore. Banda Naira: Yayasan Warisan dan Budaya Banda Naira, p. 171-2.

- Leonard Andaya (1993), p. 164.

- Leonard Andaya (1981) The heritage of Arung Palakka. The Hague: Nijhoff, p. 306.

- Leonard Andaya (1993), p. 190.

- Leonard Andaya (1993), p. 179-85.

- C.F. van Fraassen (1987), Vol. II, p. 20-1.

- C.F. van Fraassen (1987), Vol. II, p. 20-1.

Mandar Syah | ||

| Preceded by Hamza |

Sultan of Ternate 1648–1675 |

Succeeded by Sibori Amsterdam |