Man-lifting kite

A man-lifting kite is a kite designed to lift a person from the ground. Historically, man-lifting kites have been used chiefly for reconnaissance and entertainment. Interest in their development declined with the advent of powered flight at the beginning of the 20th century.

Early history

Man-carrying kites are believed to have been used extensively in ancient China, for both civil and military purposes and sometimes enforced as a punishment.[1]

The (636) Book of Sui records that the tyrant Gao Yang, Emperor Wenxuan of Northern Qi (r. 550-559), executed prisoners by ordering them to 'fly' using bamboo mats. For his Buddhist initiation ritual at the capital Ye, the emperor parodied the Buddhist ceremonial fangsheng 放生 "releasing caged animals (usually birds and fish)".[2] The (1044) Zizhi Tongjian records that in 559, all the condemned kite test pilots died except for Eastern Wei prince Yuan Huangtou.

Gao Yang made Yuan Huangtou [Yuan Huang-Thou] and other prisoners take off from the Tower of the Phoenix attached to paper owls. Yuan Huangtou was the only one who succeeded in flying as far as the Purple Way, and there he came to earth.[3]

The Purple Way (紫陌) road was 2.5 kilometres from the approximately 33-metre Golden Phoenix Tower (金凰台). These early manned kite flights presumably "required manhandling on the ground with considerable skill, and with the intention of keeping the kites flying as long and as far as possible."[4]

Stories of man-carrying kites also occur in Japan, following the introduction of the kite from China around the seventh century AD.[5] In one such story the Japanese thief Ishikawa Goemon (1558–1594) is said to have used a man-lifting kite to allow him to steal the golden scales from a pair of ornamental fish images which were mounted on the top of Nagoya Castle. His men manoeuvered him into the air on a trapeze attached to the tail of a giant kite. He flew to the rooftop where he stole the scales, and was then lowered and escaped. It is said that at one time there was a law in Japan against the use of man-carrying kites.[6]

In 1282, the European explorer Marco Polo described the Chinese techniques then current and commented on the hazards and cruelty involved. To foretell whether a ship should sail, a man would be strapped to a kite having a rectangular grid framework and the subsequent flight pattern used to divine the outlook.[7]

17th to early 20th centuries

In the 17th century, Japanese architect Kawamura Zuiken used kites to lift his workmen during construction. In the 1820s British inventor George Pocock developed man-lifting kites, using his own children as guinea pigs.

In the early 1890s, Captain B.F.S Baden-Powell, brother of the founder of the scouting movement and soon to become President of the Aeronautical Society of Great Britain, developed his "Levitor" kite, a hexagonal-shaped kite intended to be used by the army in order to lift a man for aerial observation or for lifting large loads such as a wireless antenna. At Pirbright Camp on June 27, 1894, he used one of the kites to lift a man 50 feet (15.25 m) off the ground. By the end of that year he was regularly using the kite to lift men above 100 ft (30.5 m). Baden-Powell's kites were sent to South Africa for use in the Boer War, but by the time they arrived the fighting was over, so they were never put into use.

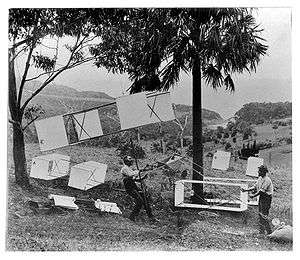

Lawrence Hargrave had invented his box kite in 1885, and from it he developed a man-carrying rig by stringing four of them in line. On 12 November 1894 he attached the rig to the ground on a long wire and lifted himself from the beach in Stanwell Park, New South Wales, reaching a height of 16 feet (4.9 m). The combined weight of his body and the rig was 208 lb (94.5 kg).

Samuel Franklin Cody was the most successful of the man-lifting kite pioneers. He patented a kite in 1901, incorporating improvements to Hargrave's double-box kite. He proposed that its man-lifting capabilities be used for military observation. After a stunt in which he crossed the English Channel in a boat drawn by a kite, he attracted enough interest from the Admiralty and the War Office for them to allow him to conduct trials between 1904 and 1908. He lifted a passenger to a new record height of 1,600 ft (488 m) on the end of a 4,000 ft (1,219 m) cable. The War Office officially adopted Cody's War Kites for the Balloon Companies of the Royal Engineers in 1906, and they entered service for observation on windy days when the Companies' observation balloons were grounded. Like Hargrave, Cody strung up a line of multiple kites to lift the aeronaut, while greatly improving on the details of the lifting gear.[8] He later built a "glider kite" which could be launched on a tether like a kite but then released and flown back down as a glider.[9] The Balloon Companies were disbanded in 1911 and were reformed as the Air Battalion of the Royal Engineers, forerunner of the Royal Air Force.[10]

Alexander Graham Bell developed a tetrahedral kite, constructed of sticks arranged in a honeycomb of triangular sections, called cells. From a one cell model at the beginning of the 1890s, Bell advanced to a 3,393 cell "Cygnet" model in the early 1900s. This 40 foot (12.2 m) long, 200 lb (91 kg) kite was towed by a steamer in Baddeck Bay, Nova Scotia on December 6, 1907 and carried a man 168 feet (51.2 m) above the sea. Roald Amundsen, the polar explorer, commissioned tests on a man-lifting kite to see whether it would be suitable for use for observation in the Arctic, but the trials were unsatisfactory, and the idea was never developed.

Modern kiting

The growth of water skiing led to the idea of adding a kite, so that the skier could take off and fly.

Flat kites

In the late 50s, individuals used the concept of being trailed by a kite above water.[11] The Australians developed flat kites originally for water ski shows. They were able to marginally control these unstable flat kites by using swing seats that allowed their entire body weight to effect pitch and roll.

Rogallo kites

It was not until the development of the Rogallo kite in the late 1940s that there was large scale interest in unpowered kite flying once again. The possibility of untethered flight on man-lifting kites eventually led to the development of hang gliders and paragliders. The sport of parasailing employs towed kites but anchored and tethered static man-lifting kites have seen little development, chiefly due to the lack of control inherent in the tethered design. Nowadays, most man-lifting is carried out on a dual line system, where the passenger on a single kite ascends a line held under tension by a train of kites. No kites are available commercially for the static-ground-based-anchored tethered flight of people. Note that many hang gliders are kited in various ways to get to give the participant desired altitude; sometimes just a short glide is needed; sometimes an altitude is desired that will provide an opportunity for the kited hang glider pilot to seek and find assistive thermals.

The Rogallo wing was invented by aerospace engineer Francis Rogallo and was the first kite to be developed with the assistance of wind tunnel testing. NASA incorporated stiffened Rogallo wings into man-lifting kites towed by ground and aero vehicles and often let in hang glide mode. Many of the kited men (eight) were released from the kited format into gliding controlled flight back to ground. The man-lifting kite and glider program of 1961 forward also produced the Paresev and gave a wing that was to be used in popular hang gliding.

Tony Prentice of UK at age 13 in 1960 made a flexible-wing-framed hangglider with rope controls without reference to the Rogallo-wing developments of NASA.[12][13] Barry Hill Palmer made several Rogallo-winged hang gliders for free-flight kiting. John Worth, associate of Francis Rogallo, exhibited the cable-stayed triangle control frame (which had been exhibited in foot-launch hang gliding in at least 1908 in Breslau) at several scales in stiffened Rogallo-wing kite glider and powered versions. Such mechanical format gave one of the avenues of template for sport use of the boomed Rogallo-wing.[14] Mike Burns in 1962 made Rogallo-winged ski-glider kites in Australia. James Hobson in 1962 showed his triangle control-bar foot-launch hang glider to the world in Sport Aviation and on USA national television. The 1962 images from NASA, Ryan, Thomas Purcell, and James Hobson aided the renaissance of hang gliding in the 1960s.

Later, John Dickenson used a boat-towing to kite himself in his adaptation of the Ryan flexible-wing craft, a version of the stiffened Rogallo-wing kite in September 1963; he did not foot-launch glide. Dickenson's Ski Wing water ski kites[15] played a role in promoting delta waterski kiting in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Prior to that, mainly truncated diamond flat kites were used in waterski sport.[16]

References

Notes

- Pelham,1976, p.9.

- Joseph Needham and Ling Wang, 1965, Science and civilisation in China: Physics and physical technology, mechanical engineering Volume 4, Part 2, page 587.

- Conan Alistair Ronan, 1994, The shorter science and civilisation in China: an abridgement of Joseph Needham's original text, Volume 4, Part 2, Cambridge University Press, p. 285.

- Ronan, 1994, p. 285.

- Pelham, 1976, pp.10-11.

- Pelham, 1976, p.11.

- Pelham, 1976, pp.9-10

- Percy Walker. 1971. Early Aviation at Farnborough, Volume I: Balloons, Kites and Airships. London. Macdonald. pp.107-112.

- "A shadow of the future". Flight International: 164. 3 September 1988.

- Garry Jenkins. 1999. Colonel Cody: and the Flying Cathedral. Simon & Schuster. p.223.

- Flat ski kites, history

- Hanggliding History - Prentice Kite

- Tony Prentice 1960 kite glider

- http://www.rogallohanggliders.com/JohnWorth/JohnWorthRWH.html

- http://grafton.nsw.free.fr/ski_wing/

- John Dickenson - aviation award Archived 2007-08-31 at the Wayback Machine

Bibliography

- Captain B.F.S. Baden-Powell. "Evolution of a Kite That Will Lift a Man" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 12, 2006. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- Joseph J. Cornish, III (April 1957). "Go Fly a Kite". Natural History Magazine. Retrieved 2 January 2007.

- Olav Gynnild. "To the Sky?: About Einar Sem-Jacobsen". Norwegian Aviation Museum. Archived from the original on 4 May 2007. Retrieved 2 January 2007.

- "Hargrave, Lawrence (1850–1915)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. 2006. Retrieved 2 January 2007.

- "Marconi Kite (replica)". The Cradle of Aviation Museum. 2001. Archived from the original on 6 October 2006. Retrieved 2 January 2007.

- Lee Scott Newman and Jay Hartley Newman. "A History of Kite Flying". Retrieved 2 January 2007.

- David Pelham. 1976. The Penguin Book of Kites. Penguin.

- "Samuel Franklin Cody and his man-lifting kite". design-technology.org. Retrieved 2 January 2007.

- "Traction Kiting Manual". American Kitefliers Association. Retrieved 2 January 2007.