Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport

Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport (IATA: MSY, ICAO: KMSY, FAA LID: MSY) (French: Aéroport international Louis Armstrong de La Nouvelle-Orléans) is an international airport under Class B airspace in Kenner, Jefferson Parish, Louisiana, United States. It is owned by the city of New Orleans and is 11 miles (18 km) west of downtown New Orleans.[3] A small portion of Runway 11/29 is in unincorporated St. Charles Parish. Armstrong International is the primary commercial airport for the New Orleans metropolitan area and southeast Louisiana.

Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport Moisant Field | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Summary | |||||||||||||||

| Airport type | Public | ||||||||||||||

| Owner | City of New Orleans | ||||||||||||||

| Operator | New Orleans Aviation Board | ||||||||||||||

| Serves | New Orleans | ||||||||||||||

| Location | Kenner, Louisiana, U.S. | ||||||||||||||

| Elevation AMSL | 4 ft / 1 m | ||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 29°59′36″N 090°15′29″W | ||||||||||||||

| Website | flymsy.com | ||||||||||||||

| Map | |||||||||||||||

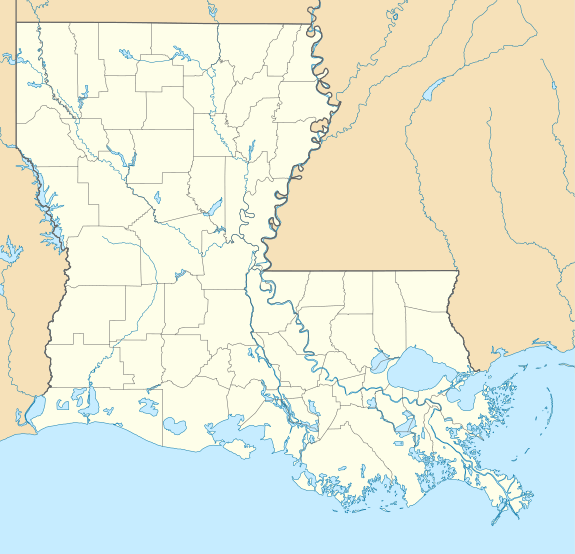

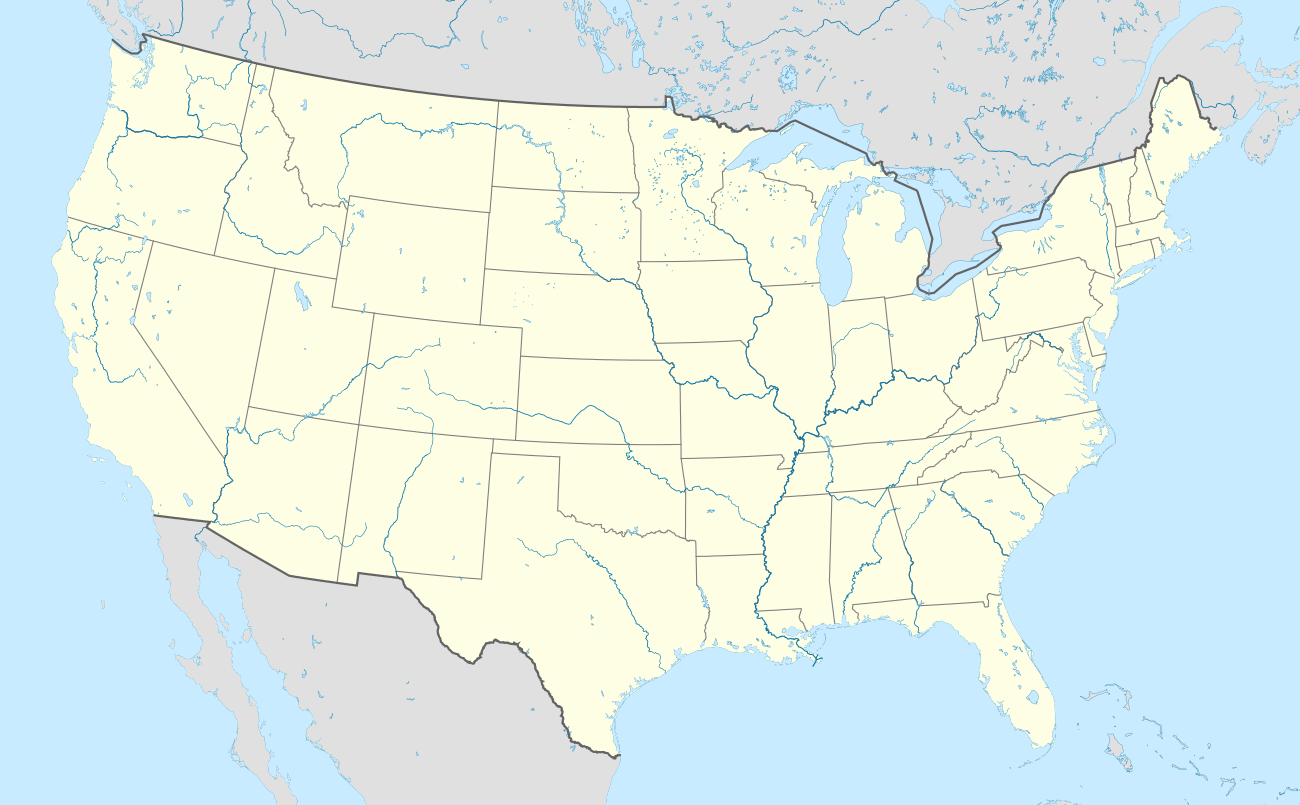

MSY Location of airport in Louisiana  MSY MSY (the United States) | |||||||||||||||

| Runways | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Statistics (2019) | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

MSY covers 1,500 acres (607 ha) of land.[3] At an average of 4.5 feet (1.4 m) above sea level, MSY is the 2nd lowest-lying international airport in the world, behind only Amsterdam Airport Schiphol in the Netherlands, which is 11 feet (3.4 m) below sea level.

History

Beginnings

Plans for a new airport began in 1940, as evidence mounted that the older Shushan Airport (New Orleans Lakefront Airport) was too small.

The airport was originally named Moisant Field after daredevil aviator John Moisant, who died in 1910 in an airplane crash on agricultural land where the airport is now located. Its IATA code MSY was derived from Moisant Stock Yards, as Lakefront Airport retained the code NEW.[4] In World War II the land became a government air base. It returned to civil control after the war and commercial service began at Moisant Field in May 1946.

On September 19, 1947, the airport was shut down as it was submerged under two feet of water in the wake of the 1947 Fort Lauderdale Hurricane's impact.

When commercial service began at Moisant Field in 1946, the terminal was a large, makeshift hangar-like building—a sharp contrast to airports in then-peer cities. A new terminal complex, designed by Goldstein Parham & Labouisse and Herbert A. Benson, George J. Riehl and built by J. A. Jones Company, debuted in 1959 towards the end of Mayor DeLesseps "Chep" Morrison's administration. The core of this structure formed much of the facility used until November 2019.[5] Retired United States Air Force Major-General Junius Wallace Jones served as airport director in the 1950s. During his term, the airport received many improvements.

The April 1957 Official Airline Guide (OAG) listed 74 weekday departures: Delta Air Lines 26, Eastern Air Lines 25, National Airlines 11, Capital Airlines 5, Southern Airways 4, and Braniff International Airways 3. Pan American World Airways had six departures each week while TACA, a Central American airline, had four. The front cover of the June 1, 1961 Capital Airlines timetable proclaimed: NEW BOEING 720 JETS - NEW YORK-ATLANTA-NEW ORLEANS - 2 ROUND TRIPS DAILY [6] Capital was then acquired by and merged into United Airlines which in 1963 was operating nonstop Boeing 720 and Sud Aviation Caravelle jet flights to Atlanta with continuing direct jet service to New York City, Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia.[7]

In 1969, Braniff International was operating direct, no change of plane service to Honolulu via a stop at Dallas with Boeing 707-320 jetliners flying the route three days a week with one of the flights also making a stop at Hilo.[8] By the early and mid 1970s, airlines operating jet service into the airport included domestic air carriers Braniff International, Continental Airlines, Delta Air Lines, Eastern Air Lines, National Airlines, Southern Airways, Texas International Airlines and United Airlines as well as Central American airlines Aviateca and SAHSA.[9][10] In 1974, two airlines had begun operating wide body jetliners into the airport: National with McDonnell Douglas DC-10 nonstops from Houston Intercontinental Airport, Los Angeles, Miami and Tampa, and Delta with Lockheed L-1011 TriStar nonstop service from LaGuardia Airport in New York City.[11] Several other airlines also operated wide body jets on domestic flights into the airport at various times during the 1980s and early 1990s including American Airlines and Pan Am with the DC-10 [12], Eastern with the L-1011 TriStar [13], and Continental and Northeastern International Airlines with the Airbus A300 with the latter air carrier operating a small hub at MSY in the spring of 1984.[14][15] Another airline which attempted to operate a hub at MSY was short-lived Pride Air which was based in New Orleans and was operating nonstop or direct Boeing 727 service from the airport to sixteen destinations including cities in California, Florida and the western U.S. in the summer of 1985.[16]

During the 1960s, Japan Airlines (JAL) used New Orleans as a technical stop on its multi-stop special service between Tokyo and São Paulo, Brazil.[17][18] On January 25, 1979, Southwest Airlines began nonstop Boeing 737-200 flights between New Orleans and Houston Hobby Airport thus marking the first time this air carrier had operated service outside of the state of Texas (Southwest had previously operated as an intrastate airline only in Texas).[19] By early 1985, air carriers operating jet service into MSY besides Southwest included American Airlines, Continental Airlines, Delta Air Lines, Eastern Air Lines, Florida Express Airlines, LACSA, Muse Air, New York Air, Northwest Airlines (operating as Northwest Orient Airlines at this time), Ozark Air Lines, Pan Am, Piedmont Airlines, Republic Airlines, Trans World Airlines (TWA), United Airlines, USAir and Western Airlines with commuter air carriers Air New Orleans and Royale Airlines operating small turboprop aircraft into the airport at this same time as well.[20]

By the time the 1959 airport terminal building opened, the name Moisant International Airport was being used for the New Orleans facility. In 1961, the name was changed to New Orleans International Airport.[21] In July 2001, to honor the 100th anniversary of Louis Armstrong's birth (August 4, 1901), the airport's name became Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport.[22]

During the administration of Morrison's successor, Vic Schiro, the government sponsored studies of the feasibility of relocating New Orleans International Airport to a new site, contemporaneous with similar efforts that were ultimately successful in Houston (George Bush Intercontinental Airport) and Dallas (Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport). This attempt got as far as recommending a site in New Orleans East; a man-made island was to be created south of I-10 and north of U.S. Route 90 in a bay of Lake Pontchartrain. In the early 1970s it was decided that the current airport should be expanded instead, leading to the construction of a lengthened main terminal ticketing area, an airport access road linking the terminal to I-10, and the present-day Concourses A and B. New Orleans Mayor Sidney Barthelemy, in office from 1986 to 1994, later reintroduced the idea of building a new international airport for the city, with consideration given to other sites in New Orleans East, as well as on the Northshore in suburban St. Tammany Parish. Only a couple months before Hurricane Katrina's landfall, Mayor Ray Nagin again proposed a new airport for New Orleans, this time to the west in Montz. These initiatives met with the same fate as 1960s-era efforts concerning construction of a new airport for New Orleans.

Post–Hurricane Katrina capacity restoration

MSY reopened to commercial flights on September 13, 2005, after the devastation of Hurricane Katrina the previous month, with four flights operated by Delta Air Lines to Atlanta and a Northwest Airlines flight to Memphis. Slowly, service from other carriers began to resume, with limited service offered by Southwest Airlines, Continental Airlines, and American Airlines. Eventually, all carriers announced their return to MSY, with the exception of America West Airlines (which merged into US Airways two weeks later) and international carrier TACA. In early 2006, Continental Airlines (since merged into United Airlines) became the first airline to return to pre-Katrina flight frequency levels, and in September 2006, to pre-Katrina seat capacity levels.

All international service into MSY was suspended while the FIS facility was closed post-Katrina. The facility reopened to chartered flights arriving from London, Manchester, Bournemouth, and Nottingham, UK—all carrying tourists in for Mardi Gras and set to depart aboard a cruise liner.

On November 21, 2006, the New Orleans Aviation Board approved an air service initiative to promote increased service to Armstrong International:

- Airlines qualify for a $0.75 credit per seat toward terminal use charges for scheduled departing seats exceeding 85% of pre-Katrina capacity levels for a twelve-month period.

- Airlines qualify for a waiver of landing fees for twelve months following the initiation of service to an airport not presently served from New Orleans.

On January 17, 2008, the city's aviation board voted on an amended incentive program that waives landing fees for the first two airlines to fly nonstop into a city not presently served from the airport. Under the new ruling, landing fees will be waived for up to two airlines flying into an "underserved destination airport." The incentive previously referred to service to a "new destination airport."

In May 2010, AirTran announced new daily nonstop service to its hub in Milwaukee utilizing Boeing 717 twin jet aircraft, which then commenced on October 7, 2010.[23] This route marked MSY's first all-new city addition since 1998. AirTran was acquired by Southwest Airlines, which in turn began operating the route. In November 2010, United Airlines announced resumption of daily nonstop service to San Francisco, the largest pre-Katrina domestic market that had yet to resume service to New Orleans. On July 16, 2012, Spirit Airlines announced nonstop service from Dallas-Fort Worth to New Orleans, commencing in January 2013. Spirit became the first all-new domestic carrier, and second all-new carrier overall (after WestJet) to announce service to MSY, since 1998.

MSY served 9,785,394 passengers in 2014, exceeding for the first time in the post-Katrina era the total passenger count of 9,733,179 achieved in 2004, the last full calendar year prior to Katrina's landfall in August 2005. A new record passenger count was set by the airport in 2015. 10,673,301 passengers were served, eclipsing the earlier record of 9.9 million passengers, set in 2000.

New terminal

On December 21, 2015, the New Orleans Aviation Board, along with the Mayor of New Orleans and City Council, approved a plan to build a new $598 million terminal building on the north side of the airport property with two concourses and 30 gates.[24] Construction began January 2016, with Hunt-Gibbs-Boh-Metro listed as the contractor at-risk.

Because of faster than expected growth at the airport, in March 2017 the New Orleans Aviation Board voted to add an approximate $178 million expansion to the new terminal complex bringing the total construction cost to $993 million, adding a third concourse and increasing the number of gates to 35.[25] Final construction costs for the project were $1.3 billion.[26]

The opening of the terminal was delayed four times. The original targeted completion date was May 2018, which would have been in time for New Orleans' 300th anniversary, but it was first delayed to October 2018. With the additional expansion the anticipated opening date was moved to February 2019 so that the entire complex could open at once. Due to a main sewer line issue, the opening of the new terminal was further pushed back to May 2019.[27] In April 2019 the opening was further delayed until Fall 2019.[28] The facility finally opened on November 6, 2019.[29]

One reason for the delay in opening the new terminal was lack of dedicated interstate access to the new facility.[30][31] New flyover-style interstate exits did not begin construction until shortly before the terminal opened and aren't expected to be completed until 2023.[30][32] Until then, the current interstate exit closest to the new terminal, Loyola Drive, has been expanded to handle the increased traffic.[33][34]

The new terminal has a centralized security checkpoint with new shops and restaurants behind the security checkpoint, including a number of restaurants run by local chefs.[35] A new garage with 2,190 parking spaces has been built, [25] and a new, privately funded airport hotel is planned. Airlines flying out of MSY have also, at their expense, funded the construction of a $39 million fuel system.[36][37]

The plans also call for demolishing concourses A, B and C of the existing southside terminal complex, while repurposing concourse D for charter services and administrative offices. The old terminal has 34 gates but only used 30 gates; the new terminal is designed for 35 gates, with an option to expand to 42.

Facilities

Terminal

The current terminal on the north side of the airfield opened in November 2019.[38] The terminal has 3 levels and 3 concourses with 35 gates. Departures and Ticketing are on Level 3, TSA Security Screening is on Level 2, and Arrivals and Baggage Claim are on Level 1.[39]

Concourse A has 6 gates and is used for International Arrivals. Airlines assigned to this concourse are Allegiant Air, American, American Eagle, Air Canada Express, Air Transat, British Airways, Condor, Copa, Sun Country and Vacation Express.[40]

Concourse B has 14 gates. Airlines assigned to this concourse are Allegiant Air, American, American Eagle, Frontier and Southwest.[41]

Concourse C has 15 gates. Airlines assigned to this concourse are Alaska, Delta, Delta Connection, JetBlue, Spirit, United and United Express.[42]

Ground transportation

Bus service between the airport and downtown New Orleans is provided by New Orleans Regional Transit Authority Airport Express Route 202 and Jefferson Transit bus E-2.[43]

Airport Shuttle has services to most hotels and hostels in the Central Business District of New Orleans for $24 per person (one-way) and $38 per person (round-trip).[44]

The terminal is served by Interstate 10 at exit 221.[45]

As of 2019, there is a flat rate fee of $36 for taxis to/from the airport to/from most hotels in the Central Business District/French Quarter (1 person/one way).[46]

The rental car facility next to the former terminal will remain in use for the new terminal.[47]

Former terminal

The former terminal of Louis Armstrong International is situated on the south side of the airfield; it closed in November 2019. The terminal contained two sections, East and West, connected by a central ticketing alley. Four concourses, A, B, C and D, were attached to the terminal, and had a total of 47 gates. The vaulted arrivals lounge at the head of Concourse C and the adjacent, western half of the ticketing alley are the remaining portions of the airport's 1959 terminal complex.

Concourse A opened in 1974 and had 6 gates. Most recently home to Northwest Airlines (since merged with Delta Air Lines) and US Airways (since merged with American Airlines), this concourse was closed first.

Concourse B opened in 1974 and had 11 gates. Southwest Airlines was the sole occupant of this concourse.

Except customs pre-cleared flights, all nonstop international arrivals were handled by Concourse C. This concourse also contained both common-use and overflow gates, available for infrequent services and charter flights as well. Concourse C has 15 Gates.

Concourse C opened on March 18, 1992 and was remodeled in 2007, according to a design by Manning Architects, after being damaged in a tornado the previous February.[48][49]

The concourse was used by Air Transat, Alaska Airlines, Allegiant Air, American Airlines, British Airways, Condor, Copa Airlines, Frontier Airlines, JetBlue, and Spirit Airlines.

Concourse D opened on December 23, 1996 and housed a Delta Sky Club in between gates D2 and D4, the sole such airline club remaining at Armstrong.[50] Originally completed with only six gates, Concourse D received a six-gate rotunda addition, designed by Sizeler Thompson Brown,[51] and inaugurated in 2011. This rotunda includes gates D7-12.[52]

Concourse D had 12 operating gates at time of closure. Delta Air Lines, United Airlines, and Air Canada Express operated from Concourse D.

Airlines and destinations

Passenger

Cargo

| Airlines | Destinations |

|---|---|

| DHL Aviation | Cincinnati, Houston–Intercontinental, Memphis |

| FedEx Express | Fort Lauderdale, Memphis, Tampa |

| UPS Airlines | Albany (GA), Louisville, Miami |

Statistics

Annual traffic

Annual passenger traffic at MSY, 2001-Present[68][69]

| Year | Passengers | Year | Passengers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 9,567,651 | 2011 | 8,548,375 |

| 2002 | 9,251,773 | 2012 | 8,600,989 |

| 2003 | 9,275,690 | 2013 | 9,207,636 |

| 2004 | 9,733,179 | 2014 | 9,785,394 |

| 2005 | 7,775,147 | 2015 | 10,673,301 |

| 2006 | 6,218,419 | 2016 | 11,139,421 |

| 2007 | 7,525,533 | 2017 | 12,009,513 |

| 2008 | 7,967,997 | 2018 | 13,122,762 |

| 2009 | 7,787,373 | 2019 | 13,644,666 |

| 2010 | 8,203,305 |

Top domestic destinations

| Rank | City | Passengers | Carriers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Atlanta, Georgia | 717,000 | Delta, Southwest, Spirit |

| 2 | Houston–Intercontinental, Texas | 351,000 | Spirit, United |

| 3 | Dallas/Fort Worth, Texas | 337,000 | American, Spirit |

| 4 | Denver, Colorado | 326,000 | Frontier, Southwest, Spirit, United |

| 5 | Los Angeles, California | 305,000 | American, Delta, Southwest, Spirit |

| 6 | Houston–Hobby, Texas | 289,000 | Southwest |

| 7 | Dallas–Love, Texas | 241,000 | Southwest |

| 8 | Charlotte, North Carolina | 237,000 | American |

| 9 | Orlando, Florida | 232,000 | Frontier, Southwest, Spirit |

| 10 | Chicago–O'Hare, Illinois | 229,000 | American, Spirit, United |

Accidents and incidents

- On November 16, 1959 National Airlines Flight 967, a Douglas DC-7 flying from Tampa to New Orleans crashed into the Gulf of Mexico.[71] All 42 passengers and crew were killed.

- On February 25, 1964, Eastern Air Lines Flight 304 operated with a Douglas DC-8 flying from New Orleans International Airport to Washington Dulles International Airport crashed nine minutes after takeoff. All 51 passengers and 7 crew members were killed.[72]

- On March 30, 1967, Delta Air Lines Flight DL9877, a Douglas DC-8-51, a training exercise with 6 crewmembers aboard, crashed on approach to MSY at 12:50 AM Central Time Zone after simulating a two-engine out approach, resulting in a loss of control. All 6 crewmembers and 13 on the ground were killed. The DC-8 crashed into a residential area, destroying several homes and a motel complex.[73]

- On March 20, 1969, Douglas DC-3 N142D, leased from Avion Airways for a private charter, crashed on landing, killing 16 of the 27 passengers and crew members on board. The aircraft was operating a domestic non-scheduled passenger flight from Memphis International Airport, Tennessee.[74]

- On July 9, 1982, Pan Am Flight 759, en route from Miami to Las Vegas, departed New Orleans International. The Boeing 727-200 jetliner took off from the east–west runway (Runway 10/28) traveling east but never gained an altitude higher than 150 feet (46 m). The aircraft traveled 4,610 feet (1405 m) beyond the end of Runway 10, hitting trees along the way, until crashing into a residential neighborhood. A total of 153 people were killed (all 145 on board and 8 on the ground). The crash was, at the time, the second-deadliest civil aviation disaster in U.S. history. The National Transportation Safety Board determined the probable cause was the aircraft's encounter with a microburst-induced wind shear during the liftoff. This atmospheric condition created a downdraft and decreasing headwind forcing the plane downward. Modern wind shear detection equipment protecting flights from such conditions is now in place both onboard planes and at most commercial airports, including Armstrong International.[75]

- On May 24, 1988 TACA Flight 110 was forced to glide without power and make an emergency landing on top of a levee east of New Orleans International Airport after flame-out in both engines of the Boeing 737-300 in a severe thunderstorm. There were no casualties and the aircraft was subsequently repaired and returned to service.[76]

- On March 21 2015 A 63 yr old man named Richard White entered Armstrong Airport carrying molotov cocktails,lighter insect killer and a machete. White began assaulting passengers and TSA. He ran through security checkpoint entering secured side of airfield. He was shot and killed by a Jefferson Parish Deputy while chasing a TSA officer with a machete.

See also

- Louisiana World War II Army Airfields

- Terry Landry, state representative and former director of airport security

References

![]()

- "Airport Data & Statistics". Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport. January 2020. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- http://www.gcr1.com/5010WEB/REPORTS/AFD03052015MSY.pdf%5B%5D

- FAA Airport Master Record for MSY (Form 5010 PDF), effective March 10, 2011.

- Welcome to the Best of New Orleans! Blake Pontchartrain March 29, 2005 Archived November 26, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- "Dedication Plaque of Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport – 2012". Airchive. 2CMedia. Archived from the original on March 23, 2013. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- http://www.timetableimages.com Archived February 2, 2001, at the Wayback Machine, June 1, 1961 Capital Airlines system timetable

- http://www.timetableimages.com Archived February 2, 2001, at the Wayback Machine, August 5, 1963 United Airlines system timetable

- http://www.timetableimages.com Archived February 2, 2001, at the Wayback Machine, May 5, 1969 Braniff International Mainland-Hawaii flight schedules effective April 14, 1969

- "MSY73". www.departedflights.com. Archived from the original on December 6, 2017. Retrieved December 5, 2017.

- http://www.departedflights.com Archived December 17, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, April 1, 1975 Official Airline Guide (OAG), New Orleans flight schedules

- http://www.departedflights.com Archived December 17, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, April 1, 1974 Official Airline Guide (OAG), New Orleans flight schedules

- http://www.departedflights.com Archived December 17, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, July 1, 1983 & Dec. 15, 1989 editions, Official Airline Guide (OAG), New Orleans flights schedules

- http://www.departedflights.com Archived December 17, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, April 1, 1981 Official Airline Guide (OAG), New Orleans flight schedules

- http://www.departedflights.com Archived December 17, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Oct. 4, 1991 Official Airline Guide (OAG), New Orleans flight schedules

- http://www.departedflights.com Archived December 17, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, May 1, 1984 Northeastern International Airlines system timetable

- http://www.departedflights.com Archived December 17, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Aug. 1, 1985 Pride Air system timetable

- "JAL timetable, 1961". timetableimages.com. Archived from the original on October 5, 2013.

- "JAL timetable, 1966". timetableimages.com. Archived from the original on December 26, 2013.

- https://www.southwestairlines.com%5B%5D, Our History 1978 to 1983

- http://www.departedflights.com Archived December 17, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Feb. 15, 1985 Official Airline Guide (OAG), New Orleans flight schedules

- "1946: Moisant Field opens on outskirts of New Orleans". The Times-Picayune. November 19, 2011. Archived from the original on February 23, 2018. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- "Dedication Plaque of Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport – 2012". Airchive. 2CMedia. Archived from the original on March 23, 2013. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- "AirTran Airways – Press Release". Pressroom.airtran.com. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- "$598 million airport terminal contract gets New Orleans Aviation Board approval". NOLA.com. Archived from the original on May 24, 2017. Retrieved May 20, 2017.

- "New Orleans Aviation Board Votes To Expand, Finance Airport's North Terminal Project - Biz New Orleans - March 2017". www.bizneworleans.com. March 17, 2017. Archived from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved May 20, 2017.

- Japhe, Brad. "This brand-new terminal might just get New Orleans off the list of USA's worst airports". USA TODAY. Retrieved November 27, 2019.

- Larino, Jennifer (September 20, 2018). "New Orleans' new airport terminal opening delayed to May 2019". nola.com. Archived from the original on March 21, 2019. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- "New Orleans Delays New MSY Airport… Again". Simple Flying. April 13, 2019. Archived from the original on April 15, 2019. Retrieved April 18, 2019.

- writer, CARLIE KOLLATH WELLS | Staff. "New Orleans airport opens new terminal: Live updates, photos, videos". NOLA.com. Retrieved November 27, 2019.

- Bridges, Tyler. "Why getting to New Orleans' new airport terminal likely 'a mess' for at least 4 years". NOLA.com. Retrieved November 27, 2019.

- Times-Picayune, Jennifer Larino, NOLA com | The. "New Orleans' new airport terminal opening delayed to fall 2019". NOLA.com. Retrieved November 27, 2019.

- writer, CHAD CALDER | Staff. "See a detailed look at the $125.6M I-10 flyover plans for New Orleans airport new terminal". NOLA.com. Retrieved November 27, 2019.

- Balogun, Rilwan. "New airport access road to open on schedule this week". Fox 8. Retrieved November 27, 2019.

- Vargas, Ramon Antonio. "Kenner council paves way for new $7 million airport access road". The Advocate. Archived from the original on September 15, 2016. Retrieved May 20, 2017.

- "Armstrong Airport board approves restaurant lineup for new terminal". NOLA.com. Archived from the original on February 26, 2017. Retrieved May 20, 2017.

- "Bond Commission approves borrowing for New Orleans airport makeover". Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- "New Orleans airport's new $807 million terminal to begin construction Jan. 4". NOLA.com. Archived from the original on December 23, 2015. Retrieved December 22, 2015.

- "This brand-new terminal might just get New Orleans off the list of USA's worst airports". Retrieved November 27, 2019.

- "The Facility - the New MSY - Get Updates".

- "The Facility - the New MSY - Get Updates".

- "The Facility - the New MSY - Get Updates".

- "The Facility - the New MSY - Get Updates".

- "Jefferson Transport Bus Routes". Jefferson Parish Transport. Archived from the original on March 26, 2013. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

- "Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport – Ground Transportation". Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport. Archived from the original on September 5, 2011. Retrieved August 24, 2011.

- "New terminal at New Orleans Airport to open on Nov. 6". WGNO. October 21, 2019. Retrieved November 27, 2019.

- "flymsy - Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport". Louis Armstrong New Orleans Airport. Retrieved November 27, 2019.

- Wendland, Tegan. "What You Need To Know About The New MSY". www.wwno.org. Retrieved November 27, 2019.

- Chatelain, Kim (March 19, 1992). "Airport Concourse is Opened to Raves". The Times-Picayune. New Orleans.

- "Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport Concourse C - Manning Architects". Archived from the original on December 17, 2012. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- Grissett, Sheila (December 24, 1996). "Airport's Big D New Concourse Sleek, Modern and Best of All, Shorter". The Times-Picayune. New Orleans.

- "Travel - Sizeler Thompson Brown Architects". Archived from the original on March 24, 2016. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- Hammer, David (October 28, 2011). "New Orleans Airport Opens Concourse D Expansion". The Times-Picayune. New Orleans. Archived from the original on October 30, 2011. Retrieved November 3, 2011.

- "Flight Schedules". Archived from the original on September 25, 2019. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "Air Transat Flight status and schedules". Flight Times. Air Transat. Archived from the original on March 22, 2018. Retrieved May 3, 2017.

- "Flight Timetable". Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- "Allegiant Air". Archived from the original on February 24, 2011. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "Flight schedules and notifications". Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "Timetables". Archived from the original on February 27, 2017. Retrieved February 26, 2017.

- "Timetable". Archived from the original on June 6, 2017. Retrieved February 26, 2017.

- "Flight Schedule". Archived from the original on August 10, 2017. Retrieved February 26, 2017.

- "FLIGHT SCHEDULES". Archived from the original on June 21, 2015. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "Frontier". Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "JetBlue Airlines Timetable". Archived from the original on July 13, 2013. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- "Check Flight Schedules". Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "Where We Fly". Archived from the original on December 23, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- "Route Map & Flight Schedule". Archived from the original on August 15, 2018. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "Timetable". Archived from the original on January 28, 2017. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport - Airport Data & Statistics". Archived from the original on February 3, 2015. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- "Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport". Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- "Air Carrier Statistics (Form 41 Traffic)- U.S. Carriers". BTS, Transportation Statistics. Bureau of Transportation Statistics. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- "ASN Aircraft accident Douglas DC-7B N4891C Gulf of Mexico Archived August 15, 2010, at the Wayback Machine." Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on December 23, 2009.

- Accident description for N8607 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on April 30, 2019.

- Accident description for N802E at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on April 30, 2019.

- "N142D Accident Description". Aviation Safety Network. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved February 9, 2011.

- Accident description for N4737 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on April 30, 2019.

- Accident description for N75356 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on April 30, 2019.

External links

![]()

- Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport, official site

- Archive index at the Wayback Machine (hosted on Greater New Orleans Free Net, GNOFN, Inc.)

- FAA Airport Diagram for MSY (PDF), effective June 18, 2020

- FAA Terminal Procedures for MSY, effective June 18, 2020