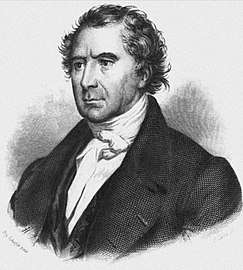

Louis-Eugène Cavaignac

Louis-Eugène Cavaignac (French pronunciation: [lwi øʒɛn kavɛɲak]; 15 October 1802 in Paris – 28 October 1857) was a French general who put down a massive rebellion in Paris in 1848, known as the June Days Uprising. This was a 4-day riot against the Provisional Government, in which Cavaignac was the newly appointed Minister of War, who soon had to be granted dictatorial powers in order to suppress the revolt. By adopting ruthless methods, he achieved his objective, though some have claimed that he spent too long preparing for the operation, allowing the mob to strengthen their defences. He received the thanks of parliament, but failed to be elected president, losing heavily to Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte.

Louis-Eugène Cavaignac | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chief of the Executive Power | |

| In office 28 June 1848 – 20 December 1848 | |

| Preceded by | François Arago as President of the Executive Commission |

| Succeeded by | Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte as President of the Republic |

| Prime Minister of France | |

| In office 28 June 1848 – 20 December 1848 | |

| Preceded by | François Arago |

| Succeeded by | Odilon Barrot |

| Minister of War | |

| In office 17 May 1848 – 29 June 1848 | |

| President | Executive Commission |

| Prime Minister | François Arago |

| Preceded by | Jean-Baptiste-Adolphe Charras |

| Succeeded by | Juchault de Lamoricière |

| In office 20 March 1848 – 5 April 1848 | |

| President | Jacques Dupont de l’Eure |

| Prime Minister | Jacques Dupont de l’Eure |

| Preceded by | Jacques Gervais Subervie |

| Succeeded by | François Arago |

| Governor of Algeria | |

| In office 24 February 1848 – 29 April 1848 | |

| President | Jacques Dupont de l’Eure |

| Prime Minister | Jacques Dupont de l’Eure |

| Preceded by | Henri d'Orléans |

| Succeeded by | Nicolas Changarnier |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 15 October 1802 Paris, French Republic |

| Died | 28 October 1857 (aged 55) Ourne, Sarthe, French Empire |

| Political party | Moderate Republican |

Early career

Louis-Eugène Cavaignac was the second son of Jean-Baptiste Cavaignac and brother of Éléonore Louis Godefroi Cavaignac.

After going through the usual course of study for the military profession, he entered the army as an engineer officer in 1824, and served in the Morea (Peloponnesus) in 1828, becoming captain in the following year. When the revolution of 1830 broke out he was stationed at Arras, and was the first officer of his regiment to declare for the new order of things. In 1831 he was removed from active duty in consequence of his declared republicanism, but in 1832 he was recalled to the service and sent to Algeria.

This continued to be the main sphere of his activity for sixteen years, and he won special distinction in his fifteen months' command of the exposed garrison of Tlemcen, a command for which he was selected by Marshal Bertrand Clausel (1836–1837), and in the defence of Cherchell (1840). Almost every step of his promotion was gained on the field of battle, and in 1844 Henri d'Orléans, Duke of Aumale himself asked for Cavaignac's promotion to the rank of maréchal de camp. This was made in the same year, and he held various district commands in Algeria up to 1848, when the provisional government appointed him governor-general of the province with the rank of general of division.

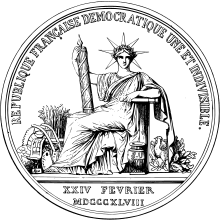

The 1848 Revolutions and the Second Republic

The post of minister of war was also offered to Cavaignac, but he refused it owing to the unwillingness of the government to quarter troops in Paris, a measure which the general held to be necessary for the stability of the new régime. On his election to the National Assembly, however, Cavaignac returned to Paris. When he arrived on 17 May he found the capital in an extremely critical state. Several riots had already taken place, and by 22 June 1848 a formidable insurrection had been organized – it would be known as the June Days Uprising.

Dictator of France

The only course now open to the National Assembly was to assert its authority by force. On 24 June, the Executive Commission was defeated by a vote of no confidence and Cavaignac appointed President of the Council of Ministers with emergency powers, effectively making him dictator. Cavaignac was called to the task of suppressing the revolt. It was no light task, as the national guard was untrustworthy, regular troops were not at hand in sufficient numbers, and the insurgents had abundant time to prepare themselves. Variously estimated at from 30,000 to 60,000 men, well armed and organized, they had entrenched themselves at every step behind formidable barricades, and were ready to avail themselves of every advantage that ferocity and despair could suggest to them.

Cavaignac failed perhaps to appreciate the political exigencies of the moment; as a soldier he would not strike his blow until his plans were matured and his forces sufficiently prepared. When the troops at last advanced in three strong columns, every inch of ground was disputed, and the government troops were frequently repulsed, requiring reinforcement by fresh regiments, until he forced his way to the Place de la Bastille and crushed the insurrection at its headquarters. The contest, which raged from 23 June to the morning of 26 June, was without doubt the bloodiest and most resolute the streets of Paris have ever seen, and the general did not hesitate to inflict the severest punishment on the rebels.

Cavaignac was censured by some for having, by his delay, allowed the insurrection to gather head; but in the chamber he was declared by a unanimous vote to have served his country well. After laying down his dictatorial powers, he continued to preside over the Executive Committee till the election of a regular president of the republic. It was expected that the suffrages of France would raise Cavaignac to that position. But the mass of the people, and especially the rural population, sick of revolution, and weary even of the moderate republicanism of Cavaignac, were anxious for a stable government. Against the five and a half million votes recorded for Louis Napoleon, Cavaignac received only a million and a half. Not without chagrin at his defeat, he withdrew into the ranks of the opposition.

In opposition

Cavaignac continued to serve as a representative during the short remainder of the republic. At the coup d'état of 2 December 1851 he was arrested along with the other members of the opposition; but after a short imprisonment at Ham he was released, and, with his newly married wife, lived in retirement till his death at Ourne (Sarthe).

Miscellaneous

For a more critical look at Cavaignac's actions from 23 to 26 June, one can find documentation in Mikhail Bakunin's Statism and Anarchy from pages 157 – 159. Cavaignac's actions are described as the inspiration to the later Prussian suppression of the National Assembly in Frankfurt and its supporters.

His son, Jacques Marie Eugène Godefroy Cavaignac was a prominent politician.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Louis-Eugène Cavaignac. |

- June Days Uprising

- 1848 Revolutions in France

- French rule in Algeria

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Jacques Gervais, baron Subervie |

Minister of War 20 March 1848 – 5 April 1848 |

Succeeded by François Arago |

| Preceded by Jean-Baptiste Adolphe Charras |

Minister of War 17 May 1848 – 28 June 1848 |

Succeeded by Louis Juchault de Lamoricière |

| Preceded by Executive Commission: François Arago Louis-Antoine Garnier-Pagès Alphonse de Lamartine Alexandre Ledru-Rollin Pierre Marie (de Saint-Georges) |

Head of State President of the Council of Ministers 28 May 1848 – 20 December 1848 |

Succeeded by Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte President of the Republic |

References