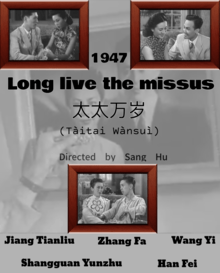

Long Live the Missus!

Long Live the Missus! (traditional Chinese: 太太萬歲; simplified Chinese: 太太万岁) is a 1947 Chinese comedy film known as one of the best comedies of the civil war era. The film was directed by Sang Hu (桑弧) with a screenplay written by the famous Chinese literary figure Eileen Chang, the pair also collaborated on the 1947 film Unending Love (Bu Liao Qing, 1947). The film was produced in Shanghai by the Wenhua Film Company. Long Live the Missus! offers a satirical depiction of the lives of women, male-female relationships, and the institution of marriage in 1940s Shanghai.

| Long Live the Missus! | |

|---|---|

| Traditional | 太太萬歲 |

| Simplified | 太太万岁 |

| Mandarin | Tàitai Wànsuì |

| Directed by | Sang Hu |

| Written by | Eileen Chang |

| Music by | Zhang Zhengjiu |

| Cinematography | Huang Shaofen |

| Edited by | Fu Jixiu |

| Color process | Black and white |

Production company | |

Release date |

|

Running time | 112 minutes |

| Country | Republic of China |

| Language | Mandarin |

The film is an example of how the writer Eileen Chang interpreted the western comedy of manners for Chinese audiences.[1] An English-subtitled version of the film, based on a translation of the filmscript by Christopher Rea, is available on YouTube.

Cast

- Jiang Tianliu as Chen Sizhen, a capable housewife

- Zhang Fa as Tang Zhiyuan, Sizhen's husband

- Shangguan Yunzhu as Shi Mimi, the mistress of Zhiyuan

- Wang Yi as Tang Zhiqin, Zhiyuan's younger sister

- Han Fei as Chen Sirui, Sizhen’s younger brother

- Lu Shan as Sizhen's mother in law

- Shi Hui as Old Mr. Chen, Sizhen's father

- Lin Zhen as Sizhen's mother

- Cui Chaoming as Lawyer Yang

- Sun Yi as Maid Zhang

- Su Yun as Ma Linlin

- Tian Zhendong as Old Mr. Zhou, Old Mr. Chen’s friend

- Jin Gang as Shopkeeper

- Cao Wei as Deputy Manager Xue

- Gao Xiao'ou as New Friend

Plot

The year is in 1947 and China is amid civil war. Chen Sizhen is a married woman in a middle-class Shanghai family whose well-intentioned white lies to help family members turn out to be increasingly counter-productive, leading to events that harm her marriage and her family finances eventually. Her husband, Tang Zhiyuan, launches a business with the financial support of his father-in-law, which Sizhen helps him secure. Feeling secure in his quick fortune, he falls prey to the seduction of a gold digger, Shi Mimi, and neglects his new company. As a result, his deputy embezzles all his money, and the company goes bankrupt. Despite his infidelity, he blames Sizhen for his misfortune and demands a divorce. Then, Sizhen forestalls an extortion attempt by outwitting Shi Mimi and bails her husband out of trouble. As a result, a grateful Zhiyuan changes his mind and wishes to cancel his proposed divorce. However, Sizhen decides that she wants to go through with a divorce anyway. At the last moment, however, Sizhen changes her mind and recommits to her marriage at the lawyer’s office. As the reconciled couple celebrate at a café, they spot and observe Mimi using her seduction methods on a new man.[2]

Production

Screenplay

Eileen Chang has already been a well-known essayist and novelist in China before entering the film industry. She became a screenwriter because of the resistance that she faced in the literary circle due to her relationship with the top collaborationist official Hu Lancheng. Filmmaking then became an alternative way as both self-expression and employment since the film industry was struggling during the postwar period and was more tolerable of talents and celebrities' moral problems. In the 1940s, Shanghai's film industry saw high demand for domestically produced romantic tragedies and transplanted Hollywood love stories in local settings. Chang was aware of this trend, and noted that Chinese films at the time were "practically all on the subject of love… Love which leads to a respectable marriage”.[3] This film, addressing the topic of love, has been associated most strongly with Eileen’s philosophical vision expressing the plight of Shanghai's middle-class women within the home and her relationships (romance, marriage, and family).[4]

As a film script rarely written by women in this period or even in the early Chinese film history and the only surviving script of the two Chang wrote that year, Long Live the Missus! embodies the "role of female creators in the anti-film mechanism of 'male gaze' and the 'female writing' against the symbolization of women".[5] It marks Eileen Chang’s signature style of a tragic comedy with a bitter-sweet ending where the characters would experience a "little reunion," but no grand finale like the audience usually anticipated. In a review of her own film Long Live the Missus!, Eileen Chang says the character "Sizhen's happy ending isn't all that happy." She elaborates that the idea of "a bittersweet mid-life probably means there will always be small pains interwoven in the happy moments, but there are moments of comfort."[6]

Sizhen's choice to reconcile with Zhiyuan might be seen controversial, especially because the "women's question" was at the center of the discussion during the Republican Era. Sizhen is not portrayed as the strong female character, who insists on her independence and pursues love. Just as Eileen Chang said, "I did not affirm or protect Chen Sizhen. I only mentioned her as such a person ". Chen Sizhen's character as the protagonist is portrayed, which is exactly the starting point and foothold of all comedy effects of “Long Live the Missus!” as a comedy film.[7] And more importantly, mentioning Sizhen only as a person, Chang refuses to discuss the women's problem as "a reductive binarism of women against men, us against them, good against evil." Such refusal has provided Long Live the Missus! the opportunity to subvert the mainstream discussion and cultural discourses at the time.[8] Chang does not depict Sizhen as a mere female victim hurt by men, and even portrays Sizhen as a person who has the ability to establish relations inside and outside of the family. Chang explains her heroine: "cleverly deal s with people in a fairly large family. Out of consideration for the interests of the whole family, she nurses various grievances. But her suffering is almost nothing compared with the agonizing sacrifices Chinese women made in the old times... We should not look at her as a victim of the social system, since her behavior is out of her own free will." Chang is aware of the discussion of the woman's question since the May Fourth Movement, and the women who suffered because of the social system, yet she believes that Long Live the Missus! could explore more potentials of the portrayal of female characters and stories.[9]

The themes and subjects of Long Live the Missus! are similar to those of Chang's wartime writings like Love in a Fallen City looking at the private space of love, marriage, family, and domestic conflicts. Long Live the Missus! integrates the Hollywood style comedy of “pursuit of happiness”, Chinese traditional love stories, and tragic romance that involves courtship, marriage, and threats of divorce.

Director Sang Hu considerably lightened the tone of Eileen Chang's original script of the film. Chang's original intention for the film was to create a more humanist film, affirming basic human nature in the form of a "silent drama." However, to ensure its box office success, the film was made to be a "Hollywood-style comedy with coincidences and witty dialogues."[10]

Sound

Sound technicians are Shen Yimin and Zhu Weigang. Shen also worked on Miserable at Middle Age in 1949 with director Sang Hu.

Sound effects, mainly non-diegetic ones, are another dimension that has enhanced the film's comicality. On several occasions, the use of sound accompanies Sizhen's laughter-arousing white lies to intensify the comic result or increase the contrast. In the forementioned lie with the bowl, every time Sizhen tries to remove the broken piece, there is background music coinciding with the visual image. Sizhen's second lie about Zhiyuan's means of travel comes with the same uplifting and cheerful tune when Zhiyuan boards and disembarks the plane. Similar to Sizhen's lies, Shi Mimi's purposely leaving a handkerchief with her lips mark in Zhiyuan's suit pocket is carried out with funny melody. Later when Sizhen accidentally pulls it out, the same music appears but only to lead to the irony that Sizhen even decides to cover up Zhiyuan's affair in front of the maid.[11]

Set Design

Set Designer Wang Yuebai is an art director and production designer employed by Wenhua Film Company. He is known for his involvement in Night Inn, and The Secret of the Magic Gourd in 1963.[12] Like Shen Weigang, Wang also collaborated with the crew again in Miserable at Middle Age.

Costume Design

The Costume designer is Qi Qiuming, who also worked on Night Inn and Miserable at Middle Age.[13]

Casting

The leading cast members including Shangguan Yunzhu, Jiang Tianliu, Zhang Fa and Shi Hui, all of whom had originally performed in stage drama during the war under Japanese rule, put in passionate performances throughout the film.[14] The film was initially planned to let Wang Danfeng play the supporting actress. However, she failed to participate in the filming, and the character was changed to perform by Shangguan Yunzhu.

Budget

Long Live the Missus! is a well-made small-budget film. Despite the often awkward camera movements (perhaps a result of the limited budgetary support), the characterization and plot are enlivened by the witty, incisive dialogues that are a distinct hallmark of Chang's wartime fiction.[15]

Themes

Marriage & Family

Long Live the Missus! tells the story of a middle-class family. Through the repressed state of women under the traditional patriarchal culture, it shows "the value crisis encountered by traditional morality, family, ethical structure and gender relations at the turn of the new era".[16] It centers on women dealing with pressure and expectation to conform to family roles as a dutiful daughter-in-law, childbearing, and a good wife. Traditionally, it was common for several generations to live under one roof together and usually the wife moved in with her husband’s family which is the case in this film. The mother runs the household and treats the daughter-in-law in a grating manner which is made clear when Sizhen is seen constantly waiting on her mother-in-law’s hand and foot.[17] Missus is an English translation of the Mandarin word tai tai, meaning “wife” or a wealthy married woman who does not work. In particular, tai tai in the context of the film refers to the socialized aspects of a wife in the domestic context and the somewhat scheming nature of the women.

While the film conveys the difficulties to become a good "taitai," another theme or moral of the film might suggest that men are unreliable. This is demonstrated when both Old Mr. Chen, Sizhen’s father, and Zhiyuan engage in affairs. Even though Old Mr. Chen was supposed to confront Zhiyuan for betraying his daughter, he too gets sucked in by the wily charms of a young woman, and teaches Zhiyuan how to lie to Sizhen in order to calm her down.

The obvious family conflict focuses on Zhiyuan’s affair. Zhiyuan is repeatedly portrayed near a mirror, creating a doubling effect. The doubling of Zhiyuan in the mirror symbolizes the two-faced quality of his character based on how he acts as a husband towards his wife and behind her back. This comedy of errors exposes the moneyed culture and the hypocrisy of Shanghai urbanities, and ridicules bourgeois materialism and decadence through its portrayal of negative male figures.[18]

In addition, the Chinese Civil Code from the 1930s gave individuals, including women a great deal of freeness to decide and manage their personal events, including freedom of marriage. According to the Civil Code, whether two people were getting married or divorced, they needed to sign the legal documents in front of two witnesses or a lawyer. This is the first time in Chinese history that women have been granted the right to divorce, it gave Chinese women a chance to leave their miserable marriage legally and freely. In the movie, like many women at the time, Sizhen was ready to save herself from suffering and apply her right to a divorce.[19]

Deception

The film also follows a theme of deception. It lampoons the deception and folly of urban, middle-class life. Through its dramatic plot twists and concocted dialogues, characters engage in theatrical gestures, role-playing, and lying, thus highlighting the essentially deceptive nature of human relations.[20] For example, from the beginning, when Maid Zhang breaks the bowl, Sizhen tries to cover it up and hide it from her mother-in-law. She is seen lying to her mother-in-law again telling her that Zhiyuan plans to take a trip to Hong Kong by boat, because it is safer, instead of by plane. Sizhen also lies to her father about Zhiyuan's mother's wealth, which misleads her father to help Zhiyuan's business, and eventually leads to the tragedy of her marriage. Even at the end of the film, she lies to Zhiqin and Sirui about coming to the lawyer's firm for celebration, not for her divorce with Zhiyuan. However, despite her attempts to conceal information, she is usually found out. Therefore, linking the theme of deception with exposure. Deception is also seen when Sizhen's little brother lies about where he bought the pineapples, when Shi Mimi lies about how she "has never told anyone this personal information before", and of course, when Zhiyuan lying about his affair with Shi Mimi. In all of these instances, the truths being covered up are inevitably revealed and the characters must face the consequences.

Chinese Comedy of Manners

Despite its Western origin, comedy of manners was appropriated by Eileen Chang for her own aesthetics. What has made Chang's opinion on comedy here remarkable is not so much her acknowledgement of laughing as natural but her insight into the coexistence of tragic and comic constituents. Comedy provides an effective channel to express the double aspect—bodily instinct and rational intellect—of human lives. This dualistic view on human's living condition is manifested in Chang's opinion on Chen Sizhen. Chang asserted:

"Eventually she has a happy ending, but she is still not particularly happy. The so-called "bittersweet middle age" probably implies that there is always some sadness mingled in their [middle-aged people] happiness. Their sadness however is not completely without comfort. I very much like these few characters' "fushi de beiai" (sadness of the floating life). But it were "fushi de beihuan" (sadness and happiness of the floating life), then it would in fact be more pitiful than "sadness of the floating life," as it contains a feeling of vast vicissitudes." [21]

There are similarities between Long Live the Missus! and the Hollywood screwball comedies, such as the focus on the love conflict/battling process of a (mismatched) couple, juxtaposition (of all male and female, capable and incapable), coincidences and chance encounters in the plot. Long Live the Mistress accounts an ordinary housewife's life. It is set in the most common locale-Shanghai's nongtang where Zhang claimed "there can be several Chen Sizhen in just one house." In contrast, most of the screwball comedies were played out against settings of sheer affluence (a Connecticut estate or a Park Avenue penthouse), properties (elegant clothes, cars, and furniture), and lines (witty and inventive repartee).[22]

Critical reception

Long Live The Missus! was widely assailed by the press and has been praised by critics across Taiwan Straits as an ‘absolutely underestimated masterpiece in the history of Chinese cinema’ and considered ‘the best Chinese comedy ever made.’Long Live The Missus! was positively received partially due to the fact that it had catered to the Shanghai audience's appetite for family melodrama and films that dealt with women in familial and social situations.[23]

Long Live the Missus! has been described as a generally apolitical film in terms of theme and tone, and it is true that issues of rich and poor do not surface in its story. However, many of Eileen Chang’s work contains themes of seduction and betrayal and this film is not without its ‘political’ points relating to women. In addition to the portrayal of ordinary Shanghai women in a time of economic crisis and cultural conflicts, this film brings awareness to gender relationships, middle-class family life, and the complex politics of Chinese cinema in post-war China.[24]

The film was attached to the biography of Eileen Chang. She was denounced as "a walking corpse from the Occupation period,"[25] and her film "encourages the audience to continue indulging in their familiar xiao shimin world of stupor and misery," by asking women to "continue making willing sacrifice."[26]

Chinese scholars Sun Yu and Zheng Xin argue that Sang Hu transformed Eileen Chang's tragic depictions of an "ephemeral age" into a more optimistic and lighthearted perspective using his comic techniques.[27]

In 2005, the film was voted #81 in the list of the Best 100 Chinese Motion Pictures at the Hong Kong Film Awards.[28]

Further reading

- Ng, K. (2008). The Screenwriter as Cultural Broker: Travels of Zhang Ailing's Comedy of Love. Modern Chinese Literature and Culture, 20(2), 131-184. Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/41482536

- Rea, Christopher (2019). "Long Live the Missus!" (1947). Translation of the full screenplay, with still images and subtitled video, MCLC Resource Center Web Publication Series.

- Fonoroff, Paul (2017). "A Golden Age of Chinese Cinema 1947-52". Berkeley Art Museum·Pacific Film Archiv: 28.

- Alison, Conner(2014). "Chinese Lawyers on the Silver Screen in the 1940s: Lawyer Yin and Lawyer Yang". Tuesday 24, June 2014.

- 陆邵阳 (2016). "桑弧创作论". 当代电影 pp. 55–57

- 张利 (2014) "论桑弧与20世纪三位文化名人的合作" 浙江工商职业技术学院学报 pp. 55–57

- 符立中 (2015) "张爱玲作品中的桑弧初探及其它" 现代中文学刊 pp. 55–57

- 符立中 (2005) "《太太万岁》与喜剧万岁" 当代电影 pp. 55–57

- Conner, A. W. (2008). Don't Change Your Husband: Divorce in Early Chinese Movies. Connecticut Law Review, 40(5), 1245-1260.

- Fu, Poshek. (2000). "Eileen Chang, Woman's Film, and Domestic Shanghai in the 1940s." Asian Cinema 11 (1): 97-113.

References

- Lin Pei-yin (December 2016). "Comicality in Long Live the Mistress and the Making of a Chinese Comedy of Manners". Tamkang Review. pp.97-119

- Ng, K. (2008). The Screenwriter as Cultural Broker: Travels of Zhang Ailing's Comedy of Love. Modern Chinese Literature and Culture, 20(2), 131-184. Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/41482536

- Fu, Poshek (March 2000). "Eileen Chang, Woman's Film, and Domestic Shanghai in the 1940s". Asian Cinema. 11 (113): 97. doi:10.1386/ac.11.1.97_1.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Fu, Poshek(2000).

- Ji Hua-yue(2018)."电影类型、性别视角与形象构建:中国早期喜剧电影中的女性形象(1949年以前)" [D].中国艺术研究院, P45

- Tang, Weijie (April 21, 2015). "张爱玲与上海电影". Xmwb.xinmin.cn.

- Ji Hua-yue(2018)."电影类型、性别视角与形象构建:中国早期喜剧电影中的女性形象(1949年以前)" [D].中国艺术研究院, P45

- Fu, Poshek (March 2000). "Eileen Chang, Woman's Film, and Domestic Shanghai in the 1940s". Asian Cinema. 11: 102. doi:10.1386/ac.11.1.97_1.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Hu, Jubin (2003). Projecting A Nation: Chinese National Cinema Before 1949 (PDF). Hong Kong University Press. p. 180. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- Hoyan, Carole (August 1996). "The Life and Works of Zhang Ailing: A Critical Study." University of British Columbia, PhD Dissertation. pp. 253-255

- Pei-yin, Lin. "Comicality in Long Live the Mistress and the Making of a Chinese Comedy of Manners." Tamkang Review, vol. 47, no. 1, 2016, p. 97+. Gale Literature Resource Center, https://link-gale-com/apps/doc/A607065160/LitRC?u=ubcolumbia&sid=LitRC&xid=c4088852. Accessed 14 June 2020.

- "Yuebai Wang". IMDB.

- "Qiuming Qi". IMDB.

- Edited by Henriot, Christian and Yeh, Wen-hsin (2012). “Visualising China, 1845-1965: Moving and Still Images in Historical Narratives” Asian Cinema, pp. 466.

- Edited by Henriot, Christian and Yeh, Wen-hsin (2012). “Visualising China, 1845-1965: Moving and Still Images in Historical Narratives” Asian Cinema, pp. 466.

- Ji Hua-yue(2018)."电影类型、性别视角与形象构建:中国早期喜剧电影中的女性形象(1949年以前)" [D].中国艺术研究院, P44-45.

- Chu, S.S.(1974). Some Aspects of Extended Kinship in a Chinese Community. The Journal of Marriage and Family, 36(3), pg. 628

- Ng, K. (2008). The Screenwriter as Cultural Broker: Travels of Zhang Ailing's Comedy of Love. Modern Chinese Literature and Culture, 20(2), 131-184. Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/41482536

- Alison W. Conner(2011). “Movie Justice: The Legal System in Pre-1949 Chinese Film” Asian-Pacific Law & Policy Journal [Vol. 12:1], University of Hawaii, University of Hawai'i Press, November 2011,p1-40.

- Ng, K. (2008). The Screenwriter as Cultural Broker: Travels of Zhang Ailing's Comedy of Love. Modern Chinese Literature and Culture, 20(2), 131-184. Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/41482536

- "Taitai wansui tiji" (Preface to Long Live the Mistress), Zhangkan (Zhang Ailing's outlook). Beijing: Economy Daily Press, 2002, 378. Print.

- Pei-yin, Lin. "Comicality in Long Live the Mistress and the Making of a Chinese Comedy of Manners." Tamkang Review, vol. 47, no. 1, 2016, p. 97+. Gale Literature Resource Center, https://link-gale-com/apps/doc/A607065160/LitRC?u=ubcolumbia&sid=LitRC&xid=c4088852. Accessed 13 June 2020.

- Ng, K. (2008). The Screenwriter as Cultural Broker: Travels of Zhang Ailing's Comedy of Love. Modern Chinese Literature and Culture, 20(2), 131-184. Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/41482536

- Conner, Alison W (2007). "Chinese Lawyers on the Silver Screen. In Corey K. Creekmur and Mark Sidel (Eds.), Cinema, Law, and the State in Asia." New York: Palgrave Macmillan, Chapter 11, pp.195-211.

- Chen Zishan ed., Siyu Zhang Ailing, p.272-75.

- Fu (2000). “Eileen Chang, Womans Film, and Domestic Shanghai in the 1940s.” Asian Cinema, pp. 110.

- 孙瑜,郑欣。(1991)“论桑弧对中国电影影戏观的继承与突破 - 以桑弧在文化编导的都市喜剧为个案”“西北工业大学艺术教育中心”。 pp. 91

- "Hong Kong Film Awards' List of The Best 100 Chinese Motion Pictures – Movie List". Mubi.com. Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

External links

- Long Live the Missus! (1947) with English subtitles on YouTube

- Long Live the Missus! on IMDb

- Long Live the Missus! on BnIAO

- Long Live the Missus! on CineMaterial

- Long Live the Missus! on Letterboxd

- Long Live the Missus! on MCLC Resource Centre

- Long Live the Missus! on Film School Rejects

- Long Live the Missus! on Hein Journal