London Naval Treaty

The London Naval Treaty (officially the Treaty for the Limitation and Reduction of Naval Armament) was an agreement between Great Britain, Japan, France, Italy and the United States, signed on 22 April 1930. Seeking to address a loophole in the formidable 1922 Washington Naval Treaty (that created tonnage limits for each nation’s surface warships), it regulated submarine warfare and limited naval shipbuilding. Ratifications were exchanged in London on 27 October 1930, and the treaty went into effect on the same day. It was largely ineffective.[1] [2]

Long name:

| |

|---|---|

Members of the United States delegation en route to the conference, January 1930 | |

| Type | Arms control |

| Context | World War I |

| Signed | 22 April 1930 |

| Location | London |

| Effective | 27 October 1930 |

| Expiration | 31 December 1936 (Except for Part IV) |

| Negotiators | |

| Signatories | |

| Parties | |

| Depositary | League of Nations |

| Language | English |

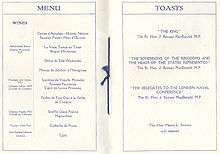

Conference

The signing of the treaty remains inextricably intertwined with the ongoing negotiations which began before the official start of the London Naval Conference of 1930, evolved throughout the progress of the official conference schedule, and continued for years thereafter.

Terms

The terms of the treaty were seen as an extension of the conditions agreed in the Washington Naval Treaty, an effort to prevent a naval arms race after World War I.

The Conference was a revival of the efforts which had gone into the Geneva Naval Conference of 1927. At Geneva, the various negotiators had been unable to reach agreement because of bad feeling between the British Government and that of the United States. The problem may have initially arisen from discussions held between President Herbert Hoover and Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald at Rapidan Camp in 1929, but a range of factors affected tensions, exacerbated by the other nations at the conference.[3]

Under the treaty, the standard displacement of submarines was restricted to 2,000 tons, with each major power being allowed to keep three submarines of up to 2,800 tons and France one. Submarine gun caliber was also restricted for the first time to 6.1 in (155 mm) with one exception, an already-constructed French submarine allowed to retain 8 in (203 mm) guns. That put an end to the 'big-gun' submarine concept pioneered by the British M class and the French Surcouf.

The treaty also established a distinction between cruisers armed with guns no greater than 6.1 in (155 mm) ("light cruisers" in unofficial parlance) from those with guns up to 8 in (203 mm) ("heavy cruisers"). The number of heavy cruisers was limited: Britain was permitted 15 with a total tonnage of 147,000, the U.S. 18 totalling 180,000, and the Japanese 12 totalling 108,000 tons. For light cruisers, no numbers were specified but tonnage limits were 143,500 tons for the U.S., 192,200 tons for the British, and 100,450 tons for the Japanese.[4]

Destroyer tonnage was also limited, with destroyers being defined as ships of less than 1,850 tons and guns not exceeding 5.1 in (130 mm). The Americans and British were permitted up to 150,000 tons and Japan 105,500 tons.

Article 22 relating to submarine warfare declared international law applied to them as to surface vessels. Also, merchant vessels that demonstrated "persistent refusal to stop" or "active resistance" could be sunk without the ship's crew and passengers being first delivered to a "place of safety."[5]

Article 8 outlined smaller surface combatants. Ships less than 2,000 tons, with guns not exceeding 6 in (152 mm), with a maximum of four gun mounts above 3 in (76 mm), without torpedo armament and not exceeding 20 kn (37 km/h) were except from tonnage limitations. The maximum allowed specifications were designed around the Bougainville-class avisos then entering French service. Warships under 600 tons where also completely exempt. This led to creative attempts to utilize the unlimited nature of the exemption with the Italian Spica-class torpedo boats, Japanese Chidori-class torpedo boats, French La Melpomène-class torpedo boats and British Kingfisher-class sloops. [6]

The next phase of attempted naval arms control was the Second Geneva Naval Conference in 1932; and in that year, Italy "retired" two battleships, twelve cruisers, 25 destroyers, and 12 submarines—in all, 130,000 tons of naval vessels (either scrapped or put in reserve).[7] Active negotiations amongst the other treaty signatories continued during the following years.[8]

That was followed by the Second London Naval Treaty of 1936.

See also

- Treaty for the Limitation of Naval Armament

- Washington Naval Treaty

- Second London Naval Treaty – List of treaties signed in London.

- Treaty of London – List of treaties signed in London.

- May 15 Incident - attempted coup in Japan

Notes

- John Maurer, and Christopher Bell, eds. At the crossroads between peace and war: the London Naval Conference in 1930 (Naval Institute Press, 2014).

- It was registered in League of Nations Treaty Series on 6 February 1931. League of Nations Treaty Series, vol. 112, pp. 66–96.

- Steiner, Zara S. (2005). The Lights that Failed: European International History 1919–1933, pp. 587-591.

- U.S. Department of State. "The London Naval Conference, 1930". Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- Treaty for the Limitation and Reduction of Naval Armaments, (Part IV, Art. 22, relating to submarine warfare). London, 22 April 1930

- John, Jordan (13 September 2016). Warship 2016. Conway. pp. 8–10. ISBN 9781844863266.

- "Italy Will Retire 130,000 tons of Navy; Two Battleships, All That She Owns, Are Included in the Sweeping Economy Move. Four New Cruisers to go [plus] Eight Old Ones, 25 Destroyers and 12 Submarines Also to Be Taken Out of Service". New York Times. 18 August 1932.

- "Naval Men See Hull on the London Talks; Admiral Leigh and Commander Wilkinson Will Sail Today to Act as Advisers". New York Times. 9 June 1934.

Further reading

- Baker, A. D., III (1989). "Battlefleets and Diplomacy: Naval Disarmament Between the Two World Wars". Warship International. XXVI (3): 217–255. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Dingman, Roger. Power in the Pacific: the origins of naval arms limitation, 1914-1922 (1976)

- Goldstein, Erik, and John H. Maurer, eds. The Washington Conference, 1921-22: Naval Rivalry, East Asian Stability and the Road to Pearl Harbor (Taylor & Francis, 1994).

- Maurer, John, and Christopher Bell, eds. At the crossroads between peace and war: the London Naval Conference in 1930 (Naval Institute Press, 2014).

- Redford, Duncan. "Collective Security and Internal Dissent: The Navy League's Attempts to Develop a New Policy towards British Naval Power between 1919 and the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty." History 96.321 (2011): 48-67.

- Roskill, Stephen. Naval Policy Between Wars. Volume I: The Period of Anglo-American Antagonism 1919-1929 (Seaforth Publishing, 2016).

- Steiner, Zara S. (2005). The Lights that Failed: European International History 1919–1933. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822114-2; OCLC 58853793

.jpg)