List of Renaissance composers

This is a list of composers active during the Renaissance period of European history. Since the 14th century is not usually considered by music historians to be part of the musical Renaissance, but part of the Middle Ages, composers active during that time can be found in the List of Medieval composers. Composers on this list had some period of significant activity after 1400, before 1600, or in a few cases they wrote music in a Renaissance idiom in the several decades after 1600.

| Lists of classical music composers by era and century | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

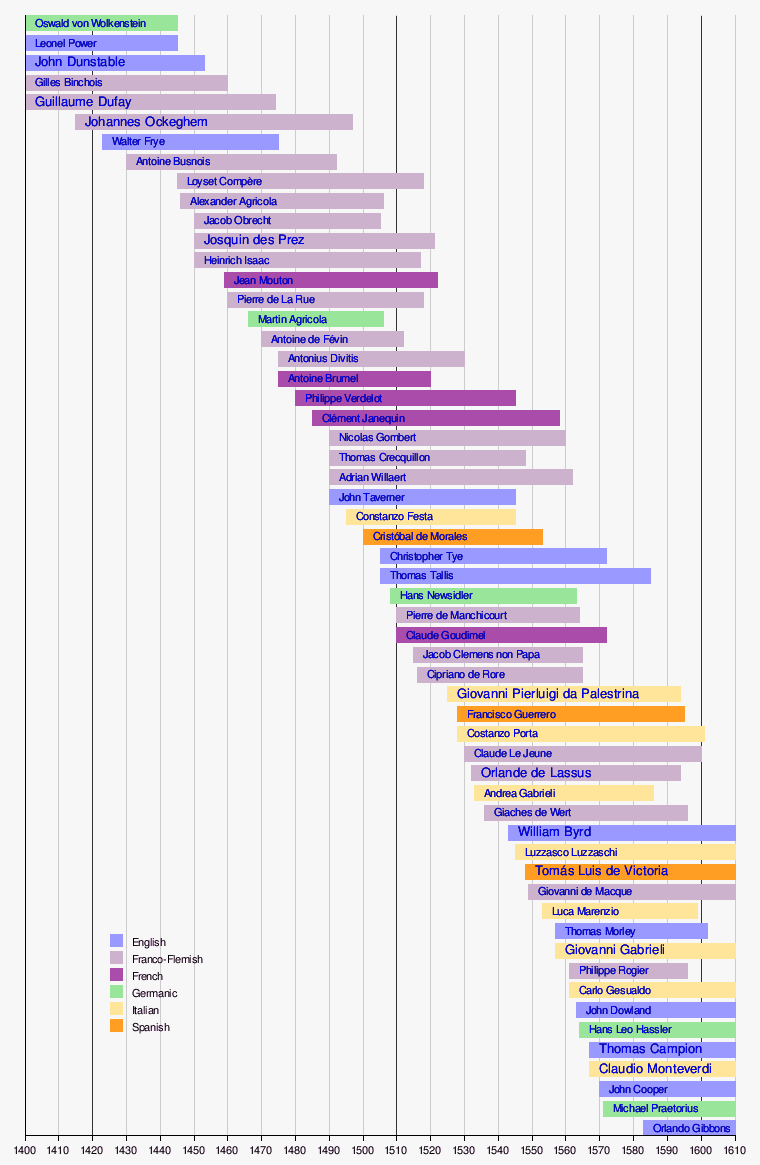

Timeline

Burgundian

The Burgundian School was a group of composers active in the 15th century in what is now northern and eastern France, Belgium, and the Netherlands, centered on the court of the Dukes of Burgundy. The school also included some English composers at the time when part of modern France was controlled by England. The Burgundian School was the first phase of activity of the Franco-Flemish School, the central musical practice of the Renaissance in Europe.

| Name | Born | Died | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Johannes Tapissier (Jean de Noyers) | c. 1370 | before 1410 | |

| Nicolas Grenon | c. 1375 | 1456 | |

| Pierre Fontaine | c. 1380 | c. 1450 | |

| Jacobus Vide | fl. 1405? | after 1433 | |

| Guillaume Legrant (Lemarcherier) | fl. 1405 | after 1449 | |

| Guillaume Dufay (Guillaume Du Fay) | 1397 | 1474 | |

| Johannes Brassart | c. 1400 | 1455 | |

| Johannes Legrant | fl. c. 1420 | after 1440 | |

| Gilles Binchois (Gilles de Bins) | c. 1400 | 1460 | |

| Hugo de Lantins | fl. c. 1420 | after 1430 | |

| Arnold de Lantins | fl. 1423 | 1431/1432 | |

| Reginaldus Libert | fl. c. 1425 | after 1435 | |

| Jean Cousin | before 1425 | after 1475 | |

| Gilles Joye | 1424/1425 | 1483 | |

| Guillaume le Rouge | fl. 1450 | after 1465 | |

| Robert Morton | c. 1430 | 1479 | English |

| Antoine Busnois | c. 1430 | 1492 | |

| Adrien Basin | fl. 1457 | after 1498 | |

| Hayne van Ghizeghem | c. 1445 | after 1476 | |

| Jean-Baptiste Besard | 1567 | 1625 | |

Franco-Flemish

The Franco-Flemish School refers, somewhat imprecisely, to the style of polyphonic vocal music composition in Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries. See Renaissance music for a more detailed description of the style. The composers of this time and place, and the music they produced, are also known as the Dutch School. However, this is a misnomer, since Dutch (as well as The Netherlands) now refers to the northern Low Countries. The reference is to modern Belgium, northern France and the south of the modern Netherlands. Most artists were born in Hainaut, Flanders and Brabant.

1370–1450

- Thomas Fabri (1380–1420)

- Johannes de Limburgia (fl. 1408–1431), also spelled Lymburgia; also called Johannes Vinandi

- Clement Liebert (fl. 1433–1454)

- Johannes Ockeghem (c. 1410–1497)

- Johannes Regis (c. 1425–c. 1496)

- Johannes Tinctoris (c. 1435–1511)

- Johannes Martini (c. 1440–1497/98)

- Petrus de Domarto (fl.c. 1445–1455)

- Alexander Agricola (1445/1446–1506)

- Johannes de Stokem (c. 1445–1487 or 1501)

- Gaspar van Weerbeke (c. 1445–after 1516)

- Johannes Pullois (died 1478), active in the Low Countries and Italy

- Josquin des Prez (c. 1450–1521)

- Heinrich Isaac (c. 1450–1517)

- Matthaeus Pipelare (c. 1450–c. 1515)

- Abertijne Malcourt (c. 1450–c. 1510)

1451–1500

- Jean Japart (fl.c. 1474–1481), active in Italy

- Jacobus Barbireau (1455–1491)

- Jacob Obrecht (1457/58–1505)

- Nycasius de Clibano (fl. 1457–1497)

- Jheronimus de Clibano (c. 1459–1503)

- Pierre de La Rue (c. 1460–1518), most famous composer of the Grande chapelle of the Habsburg court

- Marbrianus de Orto (c. 1460–1529)

- Johannes Prioris (c. 1460?–c. 1514)

- Antonius Divitis (c. 1470–c. 1530)

- Johannes Ghiselin (fl. 1491–1507)

- Nicolas Champion (c. 1475–1533)

- Jacotin (died 1529), also called Jacob Godebrye

- Noel Bauldeweyn (c. 1480–after 1513)

- Jean Richafort (c. 1480–1547)

- Benedictus Appenzeller (1480 to 1488–after 1558), served Mary of Hungary for most of his career

- Pierre Moulu (c. 1485–c. 1550), active in France

- Pierre Passereau (fl. 1509–1547), popular composer of chansons in the 1530s

- Adrian Willaert (c. 1490–1562), founder of the Venetian School; active in Italy; influential as a teacher as well as a composer

- Lupus Hellinck (c. 1494–1541)

- Nicolas Gombert (c. 1495–c. 1560), prominent contrapuntist of generation after Josquin; worked for Charles V

- Adrianus Petit Coclico (1499–after 1562)

- Philip van Wilder (1500–1554), active in England

- Arnold von Bruck (c. 1500–1554), especially active in German-speaking areas during the early Reformation period

- Jacques Buus (c. 1500–1565), active at Venice, and assisted in the development of the instrumental ricercar

- Cornelius Canis (c. 1500 to 1510–1561), music director for Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, in the 1540s and 1550s, after Nicolas Gombert

1501–1550

- Gilles Reingot (fl. 1501–1530)

- Thomas Crecquillon (c. 1505–1557), a member of Charles V's imperial chapel

- Jacquet de Berchem (c. 1505–before 1567), early madrigalist

- Jean de Latre (c. 1505/1510–1569)

- Johannes Lupi (c. 1506–1539)

- Jacques Arcadelt (c. 1507–1568), most famous of the early madrigalists

- Tielman Susato (c. 1510/15–after 1570), also spelled Tylman; was also an influential music publisher

- Jheronimus Vinders (fl. 1525–1526), active at Ghent; influenced by Josquin

- Jean Courtois (fl. 1530–1545), Flemish or French, active at Cambrai

- Jacob Clemens non Papa (c. 1510/1515–c. 1555), also known as Jacques Clément

- Ghiselin Danckerts (c. 1510–c. 1565), active in Rome

- Pierre de Manchicourt (c. 1510–1564), active in Spain

- Jan Nasco (c. 1510–1561), active in northern Italy

- Dominique Phinot (c. 1510–c. 1556), active in Italy and southern France

- Nicolas Payen (c. 1512–c. 1559), Maestro di capilla for Philip II of Spain after Cornelius Canis

- Hubert Naich (c. 1513–c. 1546), active in Rome

- Cypriano de Rore (c. 1515–1565)

- Hubert Waelrant (c. 1517–1595)

- Perissone Cambio (c. 1520–c. 1562)

- Severin Cornet (c. 1520–1582)

- Philippe de Monte (1521–1603), prolific composer of madrigals

- Simon Moreau (fl. 1553–1558)

- Jean de Bonmarché (c. 1525–1570)

- Jacobus Vaet (c. 1529–1567)

- Cornelis Symonszoon Boscoop (before 1531–1573)

- Jacobus de Kerle (1531/1532–1591)

- Orlande de Lassus (c. 1532–1594), also Orlando di Lasso, Roland de Lassus

- Giaches de Wert (1535–1596), active in Italy

- Johannes Matelart (before 1538–1607), or Ioanne Matelart

- Jhan Gero (fl. 1540–1555), active in Venice, Italy

- Jacob Regnart (1540s–1599)

- Andreas Pevernage (1542/3–1591)

- Antonino Barges (fl. 1546–1565), active in Italy

- George de La Hèle (1547–1586), active in the Habsburg chapels of Spain and the Low Countries

- Balduin Hoyoul (1547/8–1594), active in Stuttgart and Munich

- Giovanni de Macque (c. 1549–1614), active in Italy

1551–1574

- Emmanuel Adriaenssen (1554–1604)

- Rinaldo del Mel (c. 1554–c. 1598), active in Italy

- Carolus Luython (1557–1620)

- Philippus Schoendorff (1558–1617)

- Philippe Rogier (c. 1561–1596), active in Spain

- Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (1562–1621)

- Cornelis Verdonck (1563–1625)

- Joachim van den Hove (1567–1620)

- Peeter Cornet (1570/1580–1633)

- Géry de Ghersem (1573/1575–1630), active in Spain and the Netherlands

- Claudio Pari (1574–after 1619), active in Italy

French

"France" here does not refer to the France of today, but a smaller region of French-speaking people separate from the area controlled by the Duchy of Burgundy. In medieval times, France was the centre of musical development with the Notre Dame school and Ars nova; this was later surpassed by the Burgundian School, but France remained a leading producer of choral music throughout the Renaissance.

1370–1450

- Richard Loqueville (died 1418)

- Baude Cordier (c. 1380–before 1440)

- Beltrame Feragut (c. 1385–c. 1450), also known as Bertrand di Vignone

- Johannes Cesaris (fl. c. 1406–1417)

- G. Dupoitt (fl. c. 1420-1430)

- Estienne Grossin (fl. 1418–1421)

- Johannes Fedé (c. 1415–1477?)

- Biquardus (fl. 1440–1450)

- Eloy d'Amerval (fl. 1455–1508)

- Firminus Caron (fl. c. 1460–c. 1475)

- Guillaume Faugues (fl. c. 1460–1475), or Fagus

- Jehan Fresneau (fl. 1468–1505)

- Philippe Basiron (c. 1449–1491)

- Loyset Compère (c. 1450–1518)

- Gilles Mureau (c. 1450–1512)

1451–1500

- Jean Mouton (c. 1459–1522)

- Antoine Brumel (c. 1460–1512/1513)

- Colinet de Lannoy (d. before 1497)

- Carpentras (c. 1470–1548)

- Antoine de Févin (c. 1470–1511/12), brother of Robert de Févin

- Mathurin Forestier (c. 1470–1535), active in Paris

- Pierrequin de Thérache (c. 1470–1528), active in Lorraine

- Jean Braconnier ('fl. from 1478; died 1512), also known as Lourdault

- Philippe Verdelot (c. 1475–before 1552), active in Italy

- Ninot le Petit (fl. c. 1500–1520)

- Antoine de Longueval (fl. 1498–1525)

- Jean l'Héritier (c. 1480–after 1551), also spelled Heretier, Lhéritier, Lirithier

- Jacquet of Mantua (1483–1559)

- Clément Janequin (c. 1485–1558)

- Sandrin (c. 1490–c. 1560), also known as Pierre Regnault

- Claudin de Sermisy (c. 1490–1562)

- Pierre Attaingnant (c. 1494–1551/1552), best known as a printer, especially of Parisian chansons

- Pierre Vermont (c. 1495–between 1527 and 1533)

- Robert de Févin (fl. late 15th century–early 16th century), brother of Antoine de Févin

- Mathieu Gascongne (fl. 1517–1518)

1501–1550

- Acourt (fl. sometime in the first half of the 15th century)

- Firmin Lebel (early 16th century–1573), active in Rome

- Hilaire Penet (? 1501–15??)

- Pierre Certon (1510/1520–1572)

- Loys Bourgeois (c. 1510–1560)

- Guillaume Le Heurteur (fl. 1530–1545)

- Jean Maillard (c. 1510–c. 1570)

- Guillaume Morlaye (c. 1510–c. 1558)

- Jean Guyot de Châtelet (c. 1512–1588)

- Claude Goudimel (c. 1514/1520–1572)

- Thoinot Arbeau (1519–1595)

- Pierre Cadéac (fl. 1538–1556)

- Pierre Clereau (fl. 1539–1570)

- Didier Lupi Second (c. 1520–after 1559)

- Lambert Courtois (c. 1520–after 1583)

- Adrian Le Roy (c. 1520–1598)

- Claude Gervaise (1525–1583)

- Simon Boyleau (fl. c. 1544–after 1586)

- Anthoine de Bertrand (c. 1530/1540–c. 1581)

- Guillaume Boni (c. 1530–1594)

- Guillaume Costeley (c. 1530–1606)

- Nicolas de La Grotte (1530–c. 1600)

- Claude Le Jeune (1530–1600)

- Jehan Chardavoine (1537–1580)

- Paschal de l'Estocart (1538/1539–after 1584)

- Nicolas Millot (fl. 1559–1590 or later)

- Joachim Thibault de Courville (fl. from c. 1567; died 1581)

- Eustache Du Caurroy (1549–1609)

- Charles Tessier (c. 1550–after 1604), active in England and Germany

1551–1600

- Fabrice Caietain (fl. 1570–1578)

- Jacques Mauduit (1557–1627)

- Jean Titelouze (1562/1563–1633)

- Julien Perrichon (1566 – c. 1600), also a lutenist

- Nicolas Formé (1567–1638)

- Pierre Guédron (1570–1620)

- Robert Ballard (c. 1572 or 1575, probably in Paris – after 1650)

- Ennemond Gaultier (1575–1651)

- Antoine Boësset (1586–1643)

- Guillaume Bouzignac (1587–1643)

- Johann Andreas Herbst (1588–1666)

- Jacques Gaultier (1592–1652)

- Charles Racquet (1597–1664)

- Pierre Gaultier d'Orleans (1599–1681)

- Étienne Moulinié (1599–1676)

- Mlle Bocquet (early 17th century – after 1660)

Italian

After the Burgundian School came to an end, Italy became the leading exponent of renaissance music and continued its innovation with, for example, the Venetian and (somewhat more conservative) Roman Schools of composition. In particular the Venetian School's polychoral compositions of the late 16th century were among the most famous musical events in Europe, and their influence on musical practice in other countries was enormous. The innovations introduced by the Venetian School, along with the contemporary development of monody and opera in Florence, together define the end of the musical Renaissance and the beginning of the musical Baroque.

1350–1470

- Zacara da Teramo (1350/60–1413/16)

- Paolo da Firenze (c. 1355 – c. 1436; a.k.a. Paolo Tenorista)

- Giovanni Mazzuoli (Giovanni degli Organi) (1360–1426), also known as Jovannes de Florentia, Giovanni degli Organi and Giovanni di Niccol

- Matteo da Perugia (fl. 1400–1416)

- Antonio da Cividale (fl.c. 1392–1421), also known as Antonius de Civitate Austrie

- Antonello da Caserta (14th century–after 1402)

- Nicolaus Ricii de Nucella Campli (fl. 1401–1420; d.after 1436)

- Ugolino da Forlì (1380–1457), also known as Ugolino da Orvieto

- Antonius Romanus (fl. 1400–1432)

- Bartolomeo da Bologna (fl. 1405–1427)

- Grazioso da Padova (fl. 1390?–1407), also known as Gratiosus de Padua

- Nicolaus Zacharie (c. 1400 or before–1466)

- Johannes de Quadris (c. 1410–? 1457)

- Guglielmo Ebreo da Pesaro (c. 1420–1484), dance master

- Antonio Cornazzano (c. 1430–1484), dancing master

- Antonius Janue (fl.c. 1460)

- Franchinus Gaffurius (1451–1522)

- Giacomo Fogliano (1468–10 April 1548)

- Marchetto Cara (c. 1470–1525?)

- Bartolomeo Tromboncino (c. 1470–c. 1535)

1471–1500

- Bartolomeo degli Organi (1474–1539)

- Vincenzo Capirola (1474–after 1548)

- Filippo de Lurano (c. 1475–c. 1520)

- Francesco Spinacino (late 15th century–after 1507)

- Joan Ambrosio Dalza (fl. 1508)

- Andrea Antico da Montona (c. 1480–after 1538)

- Marco Dall'Aquila (c. 1480–after 1538)

- Maistre Jhan (c. 1485–1538), early madrigalist, active at Ferrara

- Gasparo Alberti (c. 1489–1560)

- Bernardo Pisano (1490–1548), possibly the earliest composer of madrigals, though not in name

- Sebastiano Festa (1490/1495–1524), early composer of madrigals; possibly related to Costanzo Festa

- Marco Antonio Cavazzoni (c. 1490–c. 1560)

- Franciscus Bossinensis (fl. 1509–1511)

- Francesco de Layolle (1492–c. 1540), Florentine composer, in the employ of the Medici; music teacher to sculptor Benvenuto Cellini

- Costanzo Festa (c. 1495–1545), early composer of madrigals; member of Sistine Chapel choir

- Francesco Canova da Milano (1497–1543)

- Mattio Rampollini (1497–c. 1553)

- Albert de Rippe (c. 1500–1551), also known as Alberto da Ripa and da Mantova

1501–1525

- Francesco Corteccia (1502–1571)

- Ambrose Lupo (1505–1591), also known as Ambrosio Lupo, de Almaliach and Lupus Italus; active in England

- Francesco Viola (died 1568), Maestro di cappella at Ferrara after Rore

- Paolo Aretino (1508–1584), also known as Paolo Antonio del Bivi

- Alfonso dalla Viola (c. 1508–c. 1573), also an instrumentalist; active in Ferrara

- Antonio Gardano (1509–1569), music printer

- Luigi Dentice (c. 1510?–1566)

- Vincenzo Ruffo (c. 1510–1587)

- Claudio Veggio (c. 1510–15??)

- Nicola Vicentino (c. 1511–1575/1576), music theorist and composer, inventor of the Archicembalo

- Nicolao Dorati (c. 1513–1593), also a trombonist; active at Lucca

- Domenico Ferrabosco (1513–1574), madrigalist; father of Alfonso Ferrabosco

- Giovanni Domenico da Nola (c. 1515–1592)

- Giandomenico Martoretta (c. 1515–1560s), Calabrian madrigalist, active in Sicily

- Agostino Agostini (died 1569), father of Lodovico Agostini

- Gioseffo Zarlino (1517–1590)

- Francesco Cellavenia (fl. 1538–1563)

- Giovanni Paolo Paladini (fl.c. 1540–1560)

- Giulio Fiesco (1519?-fl. 1550–1570), madrigalist, active at Ferrara

- Giovanni Animuccia (c. 1520–1571)

- Vincenzo Galilei (c. 1520–1591), father of composer Michelagnolo Galilei and astronomer and physicist Galileo Galilei

- Francesco Portinaro (c. 1520–after 1577), madrigalist, native of Padua

- Hoste da Reggio (c. 1520–1569), madrigalist, active at Milan and Bergamo

- Ippolito Ciera (fl. 1546–1564), minor madrigalist, active at Treviso; follower of Willaert

- Girolamo Parabosco (c. 1524–1577), minor member of the Venetian School

- Girolamo Cavazzoni (c. 1525–after 1577)

- Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (c. 1525–1594)

- Baldassare Donato (1525/1530–1603)

1526–1550

- Annibale Padovano (1527–1575)

- Costanzo Porta (c. 1529–1601)

- Giovanni Battista Conforti (fl. c. 1550–1570)

- Fabritio Caroso (c. 1530–after 1600)

- Giorgio Mainerio (c. 1530/1540–1582)

- Gianmatteo Asola (c. 1532–1609)

- Andrea Gabrieli (1532/1533–1585), uncle of Giovanni Gabrieli

- Claudio Merulo (1533–1604)

- Francesco Soto de Langa (1534–1619)

- Lodovico Agostini (1534–1590), illegitimate son of Agostino Agostini

- Cesare Negri (1535–1605), dance master

- Ippolito Chamaterò (1535/1540–after 1592), active in several cities in northern Italy; composed both sacred and secular music

- Marc'Antonio Ingegneri (1535/1536–1592), madrigalist and teacher of Monteverdi; active at Cremona

- Rocco Rodio (c. 1535–after 1615)

- Annibale Stabile (c. 1535–1595)

- Pietro Taglia (fl. c. 1555–1565), madrigalist in Milan; follower of Cipriano de Rore

- Antonio Valente (fl. 1565–1580)

- Pietro Vinci (c. 1535–1584), madrigalist; founder of the Sicilian school

- Annibale Zoilo (c. 1537–1592)

- Stefano Felis (c. 1538?–1603)

- Fabrizio Dentice (1539?–1581)

- Giovanni Dragoni (c. 1540–1598)

- Filippo Azzaiolo (fl. 1557–1569)

- Maddalena Casulana (c. 1540–c. 1590)

- Giovanni Ferretti (c. 1540–after 1609)

- Alessandro Striggio (c. 1540–1592), musician to the Medici; composer of the colossal 60-voice Missa sopra Ecco sì beato giorno

- Vincenzo Bellavere (c. 1540/1541–1587)

- Francesco Rovigo (1540/1541–1597), composed liturgical music and madrigals; active at Mantua and Graz

- Gioseffo Guami (1542–1611), also known as Gioseffo da Lucca

- Alfonso Ferrabosco the elder (1543–1588), active in England

- Giovanni Maria Nanino (1543/1544–1607), also spelled Nanini; brother of Giovanni Bernardino Nanino

- Ascanio Trombetti (1544–1590)

- Gioseppe Caimo (c. 1545–1584), active at Milan; madrigalist and organist

- Luzzasco Luzzaschi (c. 1545–1607), late madrigalist at Ferrara

- Francesco Soriano (c. 1548–1621)

- Girolamo Dalla Casa (fl. from 1568; died 1601)

- Ippolito Baccusi (c. 1550–1609)

- Emilio de' Cavalieri (c. 1550–1602)

- Cesario Gussago (c. 1550–1612)

- Pomponio Nenna (c. 1550–1613)

- Riccardo Rognoni (c. 1550–c. 1620)

- David Sacerdote (1550–1625), earliest known Jewish composer of polyphonic music, active at Mantua

- Orazio Vecchi (1550–1605)

- Girolamo Conversi (fl. c. 1572–1575)

1551–1586

- Giulio Caccini (1551–1618), one of the founders of opera

- Benedetto Pallavicino (c. 1551 – 1601)

- Girolamo Belli (1552 – c. 1620)

- Luca Marenzio (c. 1553 – 1599)

- Paolo Bellasio (1554–1594)

- Cosimo Bottegari (1554–1620)

- Girolamo Diruta (c. 1554 – after 1610)

- Giovanni Giacomo Gastoldi (c. 1554 – 1609)

- Giovanni Gabrieli (1554/1557–1612), nephew of Andrea Gabrieli

- Paolo Quagliati (1555–1628)

- Giovanni Croce (c. 1557 – 1609)

- Alfonso Fontanelli (1557–1622)

- Giovanni Bassano (c. 1558 – 1617)

- Scipione Stella (1558/1559–1622)

- Felice Anerio (c. 1560 – 1614), brother of Giovanni Francesco Anerio

- Giulio Belli (c. 1560 – c. 1621)

- Dario Castello (c. 1560 – c. 1658)

- Giovanni Bernardino Nanino (1560–1623), brother of Giovanni Maria Nanino

- Lodovico Grossi da Viadana (1560–1627)

- Scipione Dentice (1560–1635)

- Carlo Gesualdo (1560–1613)

- Ruggiero Giovannelli (c. 1560 – 1625)

- Antonio Il Verso (c. 1560 – 1621)

- Stefano Rossetto (fl. 1560–1580), active in Italy and Germany

- Leone Leoni (c. 1560 – 1627), maestro di cappella at Vicenza

- Jacopo Peri (1561–1633)

- Francesco Usper (c. 1561 – 1641), also known as Spongia

- Giulio Cesare Martinengo (1564 or 1568–1613)

- Erasmo Marotta (1565–1641), Sicilian composer

- Paola Massarenghi (born 1565; fl. 1585)

- Ascanio Mayone (1565–1627)

- Simone Molinaro (1565–1615)

- Alessandro Piccinini (1566–1638)

- Lucia Quinciani (c. 1566 – fl. 1611)

- Girolamo Giacobbi (1567–1629)

- Lorenzo Allegri (1567–1648)

- Giovanni Francesco Anerio (c. 1567 – buried 1630), brother of Felice Anerio

- Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643)

- Massimo Troiano (fl. 1567 to 1570 – after 1570)

- Adriano Banchieri (1568–1634)

- Bartolomeo Barbarino (1568–1617 or later)

- Orazio Bassani (before 1570–1615)

- Diomedes Cato (c. 1570 – after 1618), worked all his life in Poland

- Giovanni Paolo Cima (1570–1622)

- Salamone Rossi (1570–1630), Jewish

- Claudia Sessa (c. 1570 – between 1613 and 1619) (ca:Claudia Sessa)

- Giovanni Battista Fontana (1571–1630)

- Giovanni Picchi (1571–1643)

- Cesarina Ricci (c. 1573 – fl. 1597)

- Francesco Rasi (1574–1621)

- Ignazio Donati (1575–1638)

- Michelagnolo Galilei (1575–1631), active in Bavaria and Poland; son of composer Vincenzo Galilei; brother of astronomer and physicist Galileo Galilei

- Stefano Venturi del Nibbio (fl. 1592–1600); active in Florence. Collaborated with Giulio Caccini on the early opera Il rapimento di Cefalo

- Vittoria Aleotti (c. 1575 – after 1620), believed to be the same person as Raffaella Aleotti (c. 1570 – after 1646)

- Giovanni Priuli (1575–1626)

- Giovanni Maria Trabaci (1575–1647)

- Stefano Bernardi (1577–1637)

- Antonio Brunelli (1577–1630)

- Sulpitia Cesis (born 1577, fl. 1619)

- Agostino Agazzari (1578–1640)

- Caterina Assandra (1580–after 1618)

- Adreana Basile (c. 1580 – c. 1640)

- Vincenzo Ugolini (1580–1638)

- Bellerofonte Castaldi (1581–1649)

- Gregorio Allegri (1582–1652), brother of Domenico Allegri

- Severo Bonini (1582–1663)

- Marco da Gagliano (1582–1643)

- Sigismondo d'India (c. 1582 – 1629)

- Giovanni Valentini (1582–1649)

- Paolo Agostino (1583–1629)

- Girolamo Frescobaldi (1583–1643)

- Antonio Cifra (1584–1629)

- Nicolò Corradini (1585–1646)

- Andrea Falconieri (1585–1656)

- Francesco Rognoni (c. 1585 – after 1626)

- Domenico Allegri (1585–1629), brother of Gregorio Allegri

- Alessandro Grandi (1586–1630)

- Stefano Landi (1586–1643)

- Claudio Saracini (1586–1630)

- Giovanni Battista Grillo (died 1622)

- Marcantonio Negri (died 1624)

- Giovanni Battista Riccio (fl. 1609-after 1621)

Serbian

- Jefimija (1349–1405), composed tuzhbalice (laments)

- Nikola the Serb (fl. late 14th century)

- Kir Stefan the Serb (second half of the 14th and 15th century)

- Isaiah the Serb (fl. second half of the 15th century)

Greek

- Francisco Leontaritis (1518–1572)

Spanish

1370–1450

- Johannes Cornago (c. 1400–after 1475)

- Juan de Urrede (c. 1430–after 1482), or Johannes de Wreede

1451–1510

- Juan de Triana (fl. c. 1460–1500)

- Francisco de la Torre (fl. 1483–1504)

- Juan de Anchieta (1462–1523)

- Juan del Encina (1468 – c. 1529)

- Francisco de Peñalosa (c. 1470 – 1528)

- Andreas De Silva (c. 1475/1480–after 1520)

- Mateo Flecha the Elder (1481–1553), or Mateu Fletxa el Vell

- Juan Pérez de Gijón (fl. c. 1460–1500)

- Luis de Milán (c. 1500–after 1561)

- Cristóbal de Morales (c. 1500 – 1553)

- Luis de Narváez (c. 1500 – between 1550 and 1560)

- Juan Vásquez (c. 1500 – c. 1560)

- Enríquez de Valderrábano (1500-after 1557)

- Miguel de Fuenllana (1500–1578)

- Bartolomé de Escobedo (c. 1505 – 1563)

- Juan Bermudo (c. 1510 – c. 1565)

- Antonio de Cabezón (c. 1510 – 1566)

- Alonso Mudarra (c. 1510 – 1580)

- Diego Ortiz (c. 1510 – c. 1570)

- Luis Venegas de Henestrosa (c. 1510 – 1570)

1511–1570

- Tomás de Santa María (c. 1515 – 1570)

- Joan Brudieu (c. 1520 – 1591)

- Rodrigo de Ceballos (c. 1525 – 1581)

- Francisco Guerrero (1528–1599)

- Hernando Franco (1532–1585), active in Guatemala and Mexico

- Hernando de Cabezón (1541–1602)

- Ginés de Boluda (c. 1545 – c. 1606)

- Ginés Pérez de la Parra (c. 1548 – 1600)

- Tomás Luis de Victoria (1548–1611)

- Vicente Espinel (1550–1624)

- Ambrosio Cotes (c. 1550 – 1603)

- Sebastián Raval (c. 1550 – 1604)

- Sebastián de Vivanco (c. 1551 – 1622)

- Alonso Lobo (c. 1555 – 1617)

- Juan Esquivel Barahona (c. 1560–after 1625)

- Sebastián Aguilera de Heredia (1561–1627)

- Joan Baptista Comes (1568–1643)

- Joan Pau Pujol (1570–1626)

- Juan Arañés (died 1649)

Cuban

- Teodora Ginés (c. 1530 – 1598), not to be confused with the later Cuban singer and former slave of the same name

Swiss

- Ludwig Senfl (c. 1486 – 1543), active in Germany

- Fridolin Sicher (1490–1546)

Danish

- Melchior Borchgrevinck (c. 1570 – 1632)

- Hans Nielsen (1580–1626)

- Mogens Pedersøn (c. 1583 – 1623)

- Hans Brachrogge (c.1590–1638)

- Truid Aagesen (fl.1593–1625)

Polish-Lithuanian

Following a period of favourable economic and political conditions at the beginning of the 16th century, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth reached the height of its powers, when it was one of the richest and most powerful countries in Europe. It encompassed an area which included present day Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, Latvia, most of modern Ukraine and portions of what is now Czech Republic, Slovakia, Russian federation and Germany. As the middle class prospered, patronage for the arts in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth increased, and also looked westward – particularly to Italy – for influences.

Considered by many musicologists as the "Golden Age of Polish music," the period was influenced by the foundation of the Collegium Rorantistarum in 1543 at the chapel in Kraków of King Sigismund I the Old. The Collegium consisted of nine singers. And although it was required that all members be Poles, foreign influence was acknowledged in the dedication of their sacred repertory, "to the noble Italian art" (Reese 1959, p. 748).

- Mikołaj Radomski (1380–15th century)

- Mikołaj z Chrzanowa (1485–1555)

- Sebastian z Felsztyna (c. 1490 – 1543), also known as Sebastian Herburt

- Jan z Lublina (late 15th century – 1540)

- Wacław z Szamotuł (c. 1520 – c. 1560)

- Cyprian Bazylik (c. 1535 – c. 1600)

- Mikołaj Gomółka (c. 1535 – c. 1609)

- Marcin Leopolita (c. 1540 – c. 1584), also known as Marcin ze Lwowa

- Jakub Polak (c. 1545 – 1605), also known as Jacob Polonais, Jakub Reys, Jacques le Polonois and Jacob de Reis; active in France

- Nicolaus Cracoviensis (first half of the 16th century), also known as Mikołaj z Krakowa

- Tomasz Szadek (c. 1550 – 1612)

- Krzysztof Klabon (c. 1550 – 1616)

- Wojciech Długoraj (c. 1557 – after 1619)

- Diomedes Cato (before 1570 – after 1618)

- Andreas Chyliński (1590 – after 1635)

- Adam Jarzębski (1590–1648)

- Mikołaj Zieleński (fl. 1611)

- Bartłomiej Pękiel (fl. 1633 – c. 1670)

Czech

- Ondřej Chrysoponus Jevíčský (1495–1592)

- Jan Simonides Montanus (1507–1587), active in Kutná Hora

- Jan Blahoslav (1523–1571)

- Jiří Rychnovský (1529–1616)

- Simon Bar Jona Madelka (c. 1530-1550-c. 1598)

- Pavel Spongopaeus Jistebnický (c. 1550–1619)

- Jan Trojan Turnovský (c. 1550–1606)

- Pavel Spongopaeus Jistebnický (1560–1616)

- Kryštof Harant z Polžic a Bezdružic (1564–1621)

- Johannes Vodnianus Campanus (1572–1622)

- Adam Václav Michna z Otradovic (c. 1600–1676)

Hungarian

- Bálint Bakfark (1507–1576)

- Sebestyén Tinódi, Lantos (c. 1510–1556)

Slovenian

- Jacobus Gallus (1550–1591), also known as Jacob Handl; active in Moravia and Bohemia

Croatian

- Ivan Lukačić (1587–1648)

Dutch

- Ghiselin Danckerts (c. 1510 – after 1565)

- Josquin Baston (c. 1515 – c. 1576)

- Cornelis Schuyt (1557–1616)

- Joachim van den Hove (c. 1567 – 1620)

- Melchior Borchgrevinck (c. 1570 – 1632)

- Cornelis Boscoop (died 1573)

- Nicolas Vallet (1583–1642)

- Jacob van Eyck (1590–1657)

- Cornelis Thymenszoon Padbrué (c. 1592 – 1670)

- Constantijn Huygens (1596–1687)

Swedish

- Andreas Düben (1597–1662)

German

1350–1400

- Hugo von Montfort (1357–1423)

- Oswald von Wolkenstein (1376/77–1445)

1401–1450

- Conrad Paumann (c. 1410 – 1473)

- Heinrich Finck (1444/1445–1527)

- Adam von Fulda (c. 1445 – 1505)

- Hans Judenkünig (c. 1450 – 1526), or Judenkönig

- Arnolt Schlick (c. 1450 – c. 1525)

1451–1500

- Paul Hofhaimer (1459–1537)

- Sebastian Virdung (c. 1465)

- Pierre Alamire (c. 1470 – 1536), active in the Low Countries

- Thomas Stoltzer (c. 1480 – 1526)

- Hans Buchner (1483–1538)

- Martin Luther (1483–1546)

- Hans Kotter (c. 1485 – 1541)

- Martin Agricola (1486–1556)

- Georg Rhau (1488–1548)

- Arnold von Bruck (c. 1490 – 1554)

- Leonhard Kleber (c. 1495 – 1556)

- Lorenz Lemlin (c. 1495 – c. 1549)

- Leonhard Päminger (1495–1567)

- Johann Walter (1496–1570)

- Hans Gerle (c. 1498 – 1570)

1501–1550

- Hans Neusiedler (1508–1563)

- Georg Forster (c. 1510 – 1568)

- Caspar Othmayr (1515–1553)

- Sigmund Hemmel (c. 1520 – 1565)

- Hermann Finck (1527–1558)

- Elias Nikolaus Ammerbach (c. 1530 – 1597)

- Matthäus Waissel (c. 1540 – 1602)

1551–1600

- Johannes Eccard (1553–1611)

- Leonhard Lechner (c. 1553 – 1606)

- Johannes Nucius (c. 1556 – 1620)

- Hieronymus Praetorius (1560–1629)

- August Nörmiger (c. 1560 – 1613)

- Elias Mertel (c. 1561 – 1626)

- Andreas Raselius (c. 1563 – 1602)

- Hans Leo Hassler (1564–1612)

- Gregor Aichinger (1565–1628)

- Christoph Demantius (1567–1643)

- Christian Erbach (1568–1635)

- Paul Peuerl (1570–1625)

- Michael Praetorius (c. 1571 – 1621)

- Moritz von Hessen-Kassel (1572–1632)

- Erasmus Widmann (1572–1634)

- Andreas Hakenberger (1574–1627)

- Melchior Franck (1579–1639)

- Johannes Hieronymus Kapsberger (1580–1651)

- Johann Stobäus (1580–1646)

- Johannes Jeep (1581/1582-1644)

- Johann Staden (1581–1634)

- Johann Daniel Mylius (c. 1583 – 1642)

- Michael Altenburg (1584–1640)

- Daniel Friderici (1584–1638)

- Johann Grabbe (1585–1655)

- Peter Hasse (1585–1640)

- Heinrich Schütz (1585–1672)

- Jacob Praetorius (1586–1651)

- Johann Hermann Schein (1586–1630)

- Paul Siefert (1586–1666)

- Samuel Scheidt (1587–1654)

- Johann Schop (1590–1667)

- Johannes Thesselius (1590–1643)

- Melchior Schildt (1592/1593-1667)

- Gottfried Scheidt (1593–1661)

- Johann Ulrich Steigleder (1593–1635)

- Heinrich Scheidemann (1595–1663)

- Johann Crüger (1598–1662)

- Thomas Selle (1599–1663)

- Delphin Strungk (1600/1601–1694)

Portuguese

1400–1475

- Pedro de Escobar (c. 1465 – after 1535)

1476–1500

- Vicente Lusitano (fl. 1550; d. after 1561)

- Bartolomeo Trosylho (c. 1500 – c. 1567)

- Heliodoro de Paiva (c. 1500 – 1552)

1501–1525

- Damião de Góis (1502–1574)

- António Carreira (c. 1520 to 1530 – 1597)

1526–1550

- Manuel Mendes (c. 1547 – 1605)

- Pedro de Cristo (c. 1550 – 1618)

1551–1575

- Manuel Rodrigues Coelho (c. 1555 – c. 1635)

- Duarte Lobo (c. 1565 – 1647)

- Gaspar Fernandes (1566–1629)

- Manuel Cardoso (1566–1650)

- Filipe de Magalhães (1571–1652)

- Estêvão de Brito (1575–1641)

- Estêvão Lopes Morago (c. 1575 – c. 1630)

1576–1625

- Manuel Machado (1590–1646)

- Manuel Correia (1600–1653)

- John IV of Portugal (1603–1656)

English

Due in part to its isolation from mainland Europe, the English Renaissance began later than most other parts of Europe. The Renaissance style also continued into a period in which many other European nations had already made the transition into the Baroque. While late medieval English music was influential on the development of the Burgundian style, most English music of the 15th century was lost, particularly during the Dissolution of the Monasteries during the time of Henry VIII. The Tudor period of the 16th century was a time of intense interest in music, and Renaissance styles began to develop with mutual influence from the mainland. Some English musical trends were heavily indebted to foreign styles, for example the English Madrigal School; others had aspects of continental practice as well as uniquely English traits. Composers included Thomas Tallis, John Dowland, Orlando Gibbons and William Byrd.

1370–1450

| Name | Born | Died | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pycard | fl. c. 1390 | after c. 1410 | Has works preserved in the first layer of the Old Hall Manuscript and elsewhere. His identity is unclear; probably English, but possibly from France. |

| Leonel Power | c. 1370 | 1445 | |

| Roy Henry | fl. 1410 | after 1410 | Very likely to be Henry V of England (1387–1422) |

| Byttering possibly Thomas Byttering | fl. c. 1410 | after 1420 | |

| John Dunstaple (or Dunstable) | c. 1390 | 1453 | |

| John Plummer | c. 1410 | c. 1483 | |

| Henry Abyngdon | c. 1418 | 1497 | |

| Walter Frye | fl. c. 1450 | 1474 | |

| William Horwood | c. 1430 | 1484 | Some of his music is collected in the Eton Choirbook. |

| John Hothby Johannes Ottobi | c. 1430 | 1487 | English theorist and composer mainly active in Italy. |

| William Hawte William Haute | c. 1430 | 1497 | |

| Richard Hygons | c. 1435 | c. 1509 | |

| Gilbert Banester | c. 1445 | 1487 | |

| Walter Lambe | c. 1450 | after 1504 | Major contributor to the Eton Choirbook. |

| Hugh Kellyk | late 15th century | 16th century? | has two surviving pieces, a five-part Magnificat and a seven-part Gaude flore virginali, in the Eton Choirbook. |

| Edmund Turges possibly the same as Edmund Sturges | 1450 | 1500 | Has a number of works preserved in the Eton Choirbook; at least three Magnificat settings and two masses have been lost. |

1451–1500

- Robert Wilkinson (c. 1450 – after 1515), or Wylkynson

- John Browne (fl. c. 1490), likely born 1453; major contributor to the Eton Choirbook

- Robert Hacomplaynt (c. 1456 – 1528), also written as Hacomplayne, Hacomblene; has a single surviving work, a setting of Salve regina, in the Eton Choirbook; a work known as Haycomplayne's Gaude, dated 1529, has been lost

- Robert Fayrfax (1464–1521), also spelled Fairfax, Fairfaux, Feyrefax

- Richard Davy (c. 1465 – c. 1507), major contributor to the Eton Choirbook

- William Cornysh the younger (c. 1468 – 1523), probably the son of William Cornysh the elder

- Richard Sampson (c. 1470 – 1554)

- Robert Cowper (c. 1474–1535/1540), also written as Cooper or Coupar; represented by a work in the Gyffard partbooks and manuscript sourcesplainsong; and a three-part Miserere Mihi in the Ritson manuscript that is much more elaborate, somewhat resembling John Taverner's responds

- Thomas Ashewell (c. 1478–after 1513), also spelled Ashwelle, Asshwell

- Hugh Aston (c. 1485 – 1558), also spelled Ashton, Assheton

- Nicholas Ludford (c. 1485 – 1557)

- Edmund Sturton (fl. late 15th – early 16th century), presumably identical with the Sturton who composed the six-part Ave Maria ancilla Trinitatis in the Lambeth Choirbook, he contributed a Gaude virgo mater Christi to the Eton Choirbook, the six voices of which cover a fifteen-note range

- John Redford (c. 1486 – 1547), one of the main contributors to The Mulliner Book

- Thomas Appleby (c. 1488 – 1563)

- John Taverner (c. 1490 – 1545)

- Henry VIII of England (1491–1547)

- Thomas Preston (died c. 1563), composed 12 Offertory settings for keyboard, including the popular Felix namque, and an alternatim organ Mass for Easter, containing the only known sequence setting of the time; his keyboard writing is extremely virtuosic for the period

1501–1550

- Thomas Tallis (c. 1505 – 1585)

- Christopher Tye (c. 1505 – ? 1572)

- John Merbecke (also Marbeck) (c. 1510 – c. 1585), produced the first musical setting for the English liturgy, publishing The Booke of Common Praier Noted, 1549; surviving works include a Missa Per arma iustitie; almost burnt as a heretic in 1543

- Osbert Parsley (1511–1585), also spelled Parsely; wrote a set of Lamentations for Holy Week

- John Sheppard (c. 1515 – 1559)

- Edward Kyrton (fl. 1540 to 1550), Miserere for keyboard in a British Museum MS

- John Black (c. 1520 – 1587)

- Thomas Caustun (c. 1520/1525–1569), or Causton

- John Blitheman (c. 1525 – 1591)

- Richard Edwardes (1525–1566), also spelled Edwards

- Thomas Whythorne (1528–1595)

- William Mundy (1529–1591), father of John Mundy; his output includes fine examples of both the large-scale Latin votive antiphon and the short English anthem, as well as Masses and Latin psalm settings; his style is vigorous and eloquent; represented in The Mulliner Book and in the Gyffard partbooks

- Robert Parsons (c. 1535 – 1572), Latin music includes antiphons, Credo quod redemptor, Domine quis habitabit, Magnificat and Jam Christus astra; also three responds from the Office of the Dead, songs (including Pandolpho), In nomine settings for ensemble, and a galliard

- Robert White (1538–1574), also spelled Whyte

- Clement Woodcock (1540–1590), also spelled Woodcoke, Woodecock; his Browning my dear is one of several pieces of the period based on a popular tune, also known as The leaves be green

- William Byrd (c. 1540 – 1623)

- Anthony Holborne (c. 1545 – 1602), also known as Olborner

- John Johnson (c. 1545 – 1594)

- Francis Cutting (1550-1595/1596)

1551–1570

- Edmund Hooper (c. 1553 – 1621), also spelled Hoop; contributed to Michael East's psalter and William Leighton's Teares, and wrote some intensely expressive anthems; has two keyboard pieces in the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book

- John Mundy (c. 1555 – 1630), son of William Mundy; published a volume of Songs and Psalms in 1594, contributed to the Triumphs of Oriana, composed English and Latin sacred music, and is represented with five pieces in the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book; his Goe from my window variations are a particularly fine example of the genre

- Thomas Morley (1557/1558–1603)

- Nathaniel Giles (c. 1558 – 1634), also spelled Gyles

- Ferdinando Richardson (1558–1618), also known as Sir Ferdinando Heybourne; there survives a keyboard Pavan and Galliard, each with variation, in the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book

- Richard Carlton (1558–1638)

- Richard Allison (c. 1560/1570–before 1610)

- William Brade (1560–1630), active in Denmark and Germany

- William Cobbold (1560–1639), organist at Norwich Cathedral (from 1594 to 1608); a single piece by him exists in Ravenscroft's 1621 collection

- Peter Philips (1560–1628), exiled to Flanders

- Thomas Robinson (1560–1610)

- John Bull (1562–1628), exiled to the Netherlands

- John Dowland (1563–1626)

- Giles Farnaby (c. 1563 – 1640)

- John Milton (c. 1563 – 1647), father of the poet John Milton; composed madrigals, one of which was printed in The Triumphs of Oriana, as well as anthems, Psalm settings, a motet, and some consort music including a six-part In nomine

- John Danyel (1564 – after 1625), also spelled Danyell; brother of the poet Samuel Daniel (spellings of the names of the two brothers differ)

- Michael Cavendish (c. 1565 – 1628)

- John Farmer (c. 1565 – 1605)

- George Kirbye (c. 1565 – 1634)

- William Leighton (c. 1565 – 1622)

- John Hilton (1565–1609), probably father of John Hilton 'the younger' (1599–1657)

- Francis Pilkington (c. 1565 – 1638), lutenist

- Thomas Campion (1567–1620), also spelled Campian; the only English composer to experiment with musique mesurée, and the first to imitate the Florentine monodists

- Philip Rosseter (c. 1568 – 1623)

- Tobias Hume (c. 1569 – 1645), responsible for the earliest known use of col legno in Western music

- Nicholas Strogers (fl. 1560–1575), also spelled Strowger, Strowgers; three (probably four) keyboard pieces in a Christ Church, Oxford, manuscript, and a Fantasia in the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book (No. 89); an In nomine exists in a Bodleian manuscript

- Thomas Bateson (c. 1570 – 1630)

- John Cooper (c. 1570 – 1626), also spelled Coperario, Coprario

- William Tisdale (born c. 1570), also spelled Tisdall

John Bull, 1562–1628

John Bull, 1562–1628

1571–1580

- Thomas Lupo (1571–1627), also known as Thomas Lupo The Elder; composer of several works, but solid attribution of many works to him or another of his relatives is difficult

- John Ward (1571–1638)

- Edward Johnson (1572–1601), contributed to Michael East's psalter and The Triumphs of Oriana and more

- Daniel Bacheler (1572–1618)

- Martin Peerson (1572–1650), may be the same person as Martin Pearson; four keyboard pieces in the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book; many works also published

- Thomas Tomkins (1572–1656)

- Ellis Gibbons (1573–1603), brother of Orlando Gibbons

- John Wilbye (1574–1638)

- John Bartlet (fl. 1606 to 1610)

- John Bennet (c. 1575 – after 1614)

- John Coprario (c. 1575 – 1626)

- Daniel Farrant (1575–1671)

- Alfonso Ferrabosco the younger (c. 1575 – 1628), illegitimate son of Alfonso Ferrabosco the elder

- William Simmes (c. 1575 – c. 1625)

- John Holmes (fl. from 1599; died 1629)

- Thomas Greaves (fl. 1604)

- Thomas Weelkes (1576–1623)

- John Maynard (c. 1577 – between 1614 and 1633), primarily known from one published work, The XIII Wonders of the World, published in London in 1611; It contains twelve songs, six duets for lute and viol, and seven pieces for lyra viol with optional bass viol

- Robert Jones (1577–1617), published five volumes of simple and melodious lute songs, and one of madrigals

- John Amner (1579–1641)

- Michael East (c. 1580 – 1648), probably the son of Thomas East

- Richard Dering (c. 1580 – 1630)

- Thomas Ford (c. 1580 – 1648)

- Richard Nicholson (died 1639), composed English and Latin church music, and consort songs, in humorous rather than melancholy vein, and contributed to The Triumphs of Oriana

- Thomas Vautor (born c. 1580/90), published a volume of five- and six-part madrigals in 1619; his best-known piece is Sweet Suffolk Owl

- Henry Youll (born c. 1580/90), his Canzonets to Three Voyces, although clearly the work of an amateur, have charm and individuality

- George Handford (fl. c. 1609), book of Ayresin MS bears a dedication to Prince Henry dated 1609, but was never published

- John Lugg (1580 – 1647/1655), also spelled Lugge; there survive nine plainsong settings, one hexachord, and three voluntaries for double organ in a Christ Church autograph MS, among others

1581–1611

- Thomas Ravenscroft (c. 1582 – c. 1633), published a book of psalms amongst others

- Thomas Simpson (1582 – c. 1628), also spelled Sympson; active in Denmark

- Orlando Gibbons (1583–1625)

- Robert Johnson (c. 1583 – 1633)

- William Corkine (fl. 1610–1617)

- John Adson (1587–1640)

- Nicholas Lanier (1588–1666), also spelled Lanière

- Walter Porter (c. 1588 – 1659), madrigalist; publications include instrumental toccatas, sinfonias and ritornellos as well as vocal pieces

- Robert Ramsey (1590s–1644), composed mythological and biblical dialogues, such as Dives and Abraham, Saul and the Witch of Endor, and Orpheus and Pluto

- Richard Mico (1590–1661), two 18th-century arrangements for viols of keyboard pavans in a MS in the British Museum survive

- Robert Dowland (1591–1641), son of John Dowland; only three works are definitely ascribed to him: two lute pieces in the 'Varietie of Lute Lessons' and one in the 'Margaret Board Lutebook'

- John Jenkins (1592–1678)

- Henry Lawes (1595–1662)

- John Wilson (1595–1674)

- John Hilton the younger (1599–1657)

- Simon Ives (1600–1662)

- William Lawes (1602–1645)

- Christopher Simpson (1602/1606-1669)

- William Child (1606–1697)

- George Jeffreys (1610–1685)

- William Young (1610–1662)

Scottish

- Robert Johnson (c. 1470 – after 1554), active in England and Scotland

- Robert Carver (1485–1570), wrote a mass on L'Homme armé (the only known by a British composer) and a nineteen-part O bone jesu

- David Peebles (fl. c. 1530–1579)

See also

There is considerable overlap near the beginning and end of this era. See lists of composers for the previous and following eras:

- List of Medieval composers

- List of Baroque composers

Sources

- Reese. 1959.

.jpg)