Lincoln, Vermont

Lincoln is a town in Addison County, Vermont, United States. The population was 1,271 at the 2010 census.[3]

Lincoln, Vermont | |

|---|---|

Seal | |

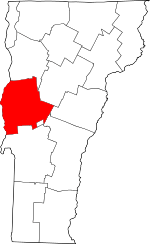

Location in Addison County and the state of Vermont. | |

| Coordinates: 44°5′31″N 72°58′53″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Vermont |

| County | Addison |

| Chartered | 1780 |

| Settled | 1790 |

| Organized | 1798 |

| Communities | Lincoln Downingville South Lincoln West Lincoln |

| Area | |

| • Total | 44.6 sq mi (115.5 km2) |

| • Land | 44.4 sq mi (115.0 km2) |

| • Water | 0.2 sq mi (0.5 km2) |

| Elevation | 1,263 ft (385 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 1,271 |

| • Density | 29/sq mi (11.1/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 05443 |

| Area code | 802 |

| FIPS code | 50-40075[1] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1462135[2] |

| Website | www |

Geography

Lincoln is located in northeastern Addison County in the Green Mountains. The Long Trail runs along the crest of the Green Mountains near the eastern border of the town, with elevations ranging from a low of 2,430 feet (740 m) at Lincoln Gap to a high of 4,006 feet (1,221 m) at the summit of Mount Abraham. The lowest elevation in the town is 840 feet (260 m) above sea level near West Lincoln, where the New Haven River exits the town.

The Lincoln Gap Road crosses the Green Mountains at Lincoln Gap, connecting the settled parts of Lincoln on the west with the town of Warren to the east. However, it is only open in the summertime, meaning the town is principally accessed via Bristol, Vermont. There are no numbered state highways in Lincoln.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 44.6 square miles (115.5 km2), of which 44.4 square miles (115.0 km2) is land and 0.19 square miles (0.5 km2), or 0.43%, is water.[3]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1800 | 97 | — | |

| 1810 | 255 | 162.9% | |

| 1820 | 278 | 9.0% | |

| 1830 | 639 | 129.9% | |

| 1840 | 770 | 20.5% | |

| 1850 | 1,057 | 37.3% | |

| 1860 | 1,070 | 1.2% | |

| 1870 | 1,174 | 9.7% | |

| 1880 | 1,368 | 16.5% | |

| 1890 | 1,255 | −8.3% | |

| 1900 | 1,152 | −8.2% | |

| 1910 | 980 | −14.9% | |

| 1920 | 841 | −14.2% | |

| 1930 | 800 | −4.9% | |

| 1940 | 745 | −6.9% | |

| 1950 | 577 | −22.6% | |

| 1960 | 481 | −16.6% | |

| 1970 | 599 | 24.5% | |

| 1980 | 870 | 45.2% | |

| 1990 | 974 | 12.0% | |

| 2000 | 1,214 | 24.6% | |

| 2010 | 1,271 | 4.7% | |

| Est. 2014 | 1,272 | [4] | 0.1% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[5] | |||

As of the census[1] of 2000, there were 1,214 people, 462 households, and 339 families residing in the town. The population density was 27.6 people per square mile (10.7/km2). There were 566 housing units at an average density of 12.9 per square mile (5.0/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 97.53% White, 0.16% African American, 0.33% Native American, 0.66% Asian, 0.08% Pacific Islander, and 1.24% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.24% of the population.

There were 462 households out of which 37.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 61.3% were married couples living together, 8.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 26.6% were non-families. 19.9% of all households were made up of individuals and 7.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.63 and the average family size was 3.02.

In the town, the age distribution of the population shows 27.1% under the age of 18, 5.9% from 18 to 24, 29.1% from 25 to 44, 27.1% from 45 to 64, and 10.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39 years. For every 100 females, there were 101.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 100.7 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $45,750, and the median income for a family was $51,369. Males had a median income of $30,455 versus $25,125 for females. The per capita income for the town was $21,092. About 4.3% of families and 5.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 9.4% of those under age 18 and 1.5% of those age 65 or over.

History

Lincoln was chartered to Colonel Benjamin Simonds and 64 associates on November 9, 1780. Simonds, as commander of the Massachusetts militia, fought at the Battle of Bennington in 1777. He named the new town in honor of his commanding officer, Major General Benjamin Lincoln (1733–1810), who had played a vital role in getting the militia to Vermont. General Lincoln was respected and well liked by his contemporaries.[6]

Lincoln, like Ferrisburgh and several other Addison County towns, was settled by members of the Society of Friends, or Quakers. The first Quakers settled in an area known as Mud Flat about 1795. As time went by and other Quakers joined the original group, the area became known as Quaker Stand. The meeting house is gone and the Society has dispersed, but one part of Lincoln village is still called Quaker Street.[6] Lincoln's town government was officially organized in 1798, when the first town meeting was held in the log cabin of early settler Jedediah Durfee.[7]

Until the latter part of the 20th century, Lincoln's economy had been centered around smallholder agriculture, ironworks, and mills. The earliest export products were potash and timber, sold by homesteading farmers after clearing their land. The town's population and economy peaked in the 1880s, when there were 15 lumber mills making shingles and clapboard operational in the town, employing around 100 men. Dairies and potato farming comprised a large remainder of the town's industry. Lincoln also grew to comprise the previous settlements of Downingsville and West, South, and Center Lincoln, bringing it to its present area of 44 square miles. The town's proximity to the New Haven River has caused numerous destructive floods in its history, in 1830, 1869, 1938, 1976 and 1998. [6]

In 1919, Lincoln-born businessman Walter S. Burnham left a significant endowment to the town in his will, resulting in the creation of the Burnham Trust, a fund intended to "be expended for educational, charitable, and musical purposes." The Trust provided funding for the construction of Burnham Hall, a community meeting place and formerly the town library, as well as establishing a scholarship fund for future Lincoln students. Burnham Hall continues to be the site of Lincoln's town meeting.[7]

Lincoln underwent a significant contraction in the mid-20th century, as its resource-based livelihoods dried up and families moved away. Dairy farms were unable to compete with larger, centralized enterprises elsewhere in the state and country. For Lincoln, the industry's death knell came in the 1980s, when the federal government offered to buy out smaller farms in an attempt to raise the price of milk and therefore make the industry more profitable; Lincoln's last dairy closed in 1992. Most of the mills and other industry also closed by the end of the century, though one pallet mill remains in operation. In 1968 Lincoln lost its post office (and thus its ZIP code) when postal services were transferred to Bristol.[8]

Today, Lincoln's population has rebounded almost to its historic peak. Its proximity to the Green Mountains, tranquility, and well-supported community services have made it attractive as a residential community. Most working age adults commute to jobs in neighboring towns, but Lincoln is still home to a general store, hotel, and multiple small-batch maple syrup producers.[6]

On September 11, 2010, the first Tibetan Buddhist nunnery in North America was consecrated in Lincoln.[9]

References

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Lincoln town, Addison County, Vermont". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

- "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2014". Archived from the original on May 23, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 16, 2015.

- "History of Lincoln" (PDF). lincolnvermont.org. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- Reed, Richard (1980). Lincoln: History of a Mountain Town (1st ed.). Town of Lincoln, Vermont. p. 105.

- Lincoln - Entering the 21st Century (1st ed.). Rutland, Vermont: The Lincoln Historical Society. 2007.

- "Buddhist monastery for women opens in Bristol". The Eagle. September 18, 2010. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) Note: The title of the article says 'Bristol' but the nunnery is actually in Lincoln.