Licinia gens

The gens Licinia was a celebrated plebeian family at Rome, which appears from the earliest days of the Republic until imperial times, and which eventually obtained the imperial dignity. The first of the gens to obtain the consulship was Gaius Licinius Calvus Stolo, who, as tribune of the plebs from 376 to 367 BC, prevented the election of any of the annual magistrates, until the patricians acquiesced to the passage of the lex Licinia Sextia, or Licinian Rogations. This law, named for Licinius and his colleague, Lucius Sextius, opened the consulship for the first time to the plebeians. Licinius himself was subsequently elected consul in 364 and 361 BC, and from this time, the Licinii became one of the most illustrious gentes in the Republic.[2][3]

Origin

The nomen Licinius is derived from the cognomen Licinus, or "upturned", found in a number of Roman gentes.[4] Licinus may have been an ancient praenomen, but few examples of its use as such are known. The name seems to be identical with the Etruscan Lecne, which frequently occurs on Etruscan sepulchral monuments.[5] Some scholars have seen evidence of an Etruscan origin for the Licinii in the tradition that Etruscan players were first brought to Rome to take part in the theatrical performances (ludi scaenici) in the consulship of Gaius Licinius Calvus, BC 364. This could, however, be coincidental, as Livy explains that the games were instituted this year in order to palliate the anger of the gods.[6] In fact, the name of Licinius appears to have been spread throughout both Latium and Etruria from a very early time, so the fact that it had an Etruscan equivalent does not definitely show that the gens was of Etruscan derivation.[3]

Praenomina

The chief praenomina used by the Licinii were Publius, Gaius, Lucius, and Marcus, all of which were very common throughout Roman history. The family occasionally used Sextus, and there is at least one instance of Gnaeus during the first century BC. Aulus was used by the Licinii Nervae. As in other Roman families, the women of the Licinii generally did not have formal praenomina, but were referred to simply as Licinia; if further distinction were needed, they would be described using various personal or family cognomina.

Branches and cognomina

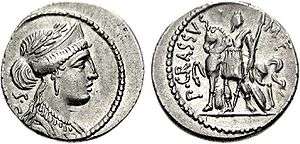

The family-names of the Licinii are Calvus (with the agnomina Esquilinus and Stolo), Crassus (with the agnomen Dives), Geta, Lucullus, Macer, Murena, Nerva, Sacerdos, and Varus. The other cognomina of the gens are personal surnames, rather than family-names; these include Archias, Caecina, Damasippus, Imbrex, Lartius, Lenticula, Nepos, Proculus, Regulus, Rufinus, Squillus, and Tegula. The only cognomina which occur on coins are Crassus, Macer, Murena, Nerva, and Stolo. A few Licinii are known without a surname; most of these in later times were freedmen.[3]

The surname Calvus was originally given to a person who was bald,[7] and it was the cognomen of the earliest family of the Licinii to distinguish itself under the Republic. The first of this family bore the agnomen Esquilinus, probably because he lived on the Esquiline Hill.[8] Stolo, a surname given to the most famous of the family, may be derived from the stola, a long outer garment or cloak, or might also refer to a branch, or sucker.[9][10] Although the family of the Licinii Calvi afterward vanished into obscurity, the surname Calvus was later borne by the celebrated orator and poet Gaius Licinius Macer, who lived in the first century BC. His cognomen Macer, designated someone who was lean.[7][11][12]

Another family of the Licinii bore the cognomen Varus, which means "crooked, bent," or "knock-kneed."[4] The Licinii Vari were already distinguished, when their surname was replaced by that of Crassus. This was a common surname, which could mean "dull, thick," or "solid," and may have been adopted because of the contrast between this meaning and that of Varus.[7][12]

The surname Dives, meaning "rich" or "wealthy," was borne by some of the Licinii Crassi.[13] It was most famous as the surname of Marcus Licinius Crassus, the triumvir, and has been ascribed to his father and brothers, but it is not altogether certain whether it originated with his father, or with the triumvir, in which case it was retroactively applied to the previous generation.[14][15][16]

Lucullus, the cognomen of a branch of the Licinii, which first occurs in history towards the end of the Second Punic War, is probably derived from lucus, a grove, or perhaps a diminutive of the praenomen Lucius. The surname does not appear on any coins of the gens.[17][18]

A family of the Licinii bore the surname Murena (sometimes, but erroneously, written Muraena), referring to the sea-fish known as the murry or lamprey, a prized delicacy since ancient times. This family came from the city of Lanuvium, to the southeast of Rome, and was said to have acquired its name because one of its members had a great liking for lampreys, and built tanks for them. The same surname occurring in other families might be said to be derived from the type of shellfish known as murex, from which a valuable dye was extracted.[17][19][20][21][22]

Of the other surnames of the Licinii might be mentioned Nerva, the surname of a family of the Licinii that flourished from the time of the Second Punic War until the early Empire, derived from nervus, "sinewy";[7] Geta, perhaps the name of a Thracian people, to whom one of the Licinii might have been compared;[23] and Sacerdos, a priest, one of a number of cognomina derived from occupations.[24][25]

Members

- This list includes abbreviated praenomina. For an explanation of this practice, see filiation.

Early Licinii

- Gaius Licinius, one of the first tribuni plebis elected, in 493 BC. He and his colleague, Lucius Albinius Paterculus, are said to have elected three others, although according to Dionysius, all five were elected by the people.[26][27]

- Publius Licinius, one of the first tribuni plebis in 493 BC. According to Dionysius he was elected by the people, although according to Livius he was one of three chosen by his colleagues.[26][27]

- Spurius Licinius, according to Livius tribunus plebis in 481 BC, although Dionysius gives his nomen as Icilius. Dionysius may be correct, as the praenomen Spurius was not used by any other members of the gens Licinia.[28][29]

Licinii Calvi

- Publius Licinius P. f. Calvus, father of the elder Esquilinus.

- Publius Licinius P. f. P. n. Calvus Esquilinus, tribunus militum consulari potestate in 400 BC; according to Livius, one of the first plebeians elected to this office, although some of the consular tribunes in 444 and 422 may also have been plebeians.[30][31][32]

- Publius Licinius P. f. P. n. Calvus Esquilinus, tribunus militum consulari potestate in 396 BC, substituted for his father, who had been elected for the second time, but declined the office on account of his advanced age.[33][34][35][36]

- Gaius Licinius P. f. P. n. Calvus, the father of Stolo, was probably a brother of the younger Esquilinus.

- Gaius Licinius P. f. P. n. Calvus, the first plebeian appointed magister equitum in 368 BC; he had previously served as consular tribune, but the year is uncertain. He was probably consul in either 364 or 361, but he has been confused with his contemporary, Gaius Licinius Calvus Stolo.[37][38][39][lower-roman 1][lower-roman 2]

- Gaius Licinius C. f. P. n. Calvus, surnamed Stolo, one of the two tribuni plebis who brought forward the lex Licinia Sextia, and who accordingly was elected consul in either 364 or 361 BC, or perhaps in both years.[lower-roman 3][40]

Licinii Vari

- Publius Licinius Varus, grandfather of the consul of 236 BC.

- Publius Licinius P. f. Varus, father of the consul.

- Gaius Licinius P. f. P. n. Varus, consul in 236 BC, carried on the war against the Corsicans and the transalpine Gauls.[41][42]

- Publius Licinius (C. f. P. n.) Varus, praetor urbanus in 208 BC; he was instructed to refit thirty old ships and find crews for twenty others, in order to protect the coast near Rome.[43]

- Gaius Licinius P. f. (C. n.) Varus, father of Publius and Gaius Licinius Crassus, consuls in 171 and 168 BC.

Licinii Crassi

- Publius Licinius P. f. P. n. Crassus Dives, censor in 208 BC and consul in 205, during the Second Punic War.

- Gaius Licinius P. f. P. n. Crassus Dives, son of the consul of 205 BC.

- Publius Licinius C. f. P. n. Crassus, consul in 171 BC, defeated by Perseus of Macedon.[44]

- Gaius Licinius C. f. P. n. Crassus, as praetor urbanus in 172 BC, was involved in the trial of Marcus Popillius Laenas. Consul in 168, he was assigned the province of Gallia Cisalpina, but brought his army to Macedonia instead.[45]

- Gaius Licinius (C. f. C. n.) Crassus, tribunus plebis in 145 BC, proposed a bill to fill vacant priesthoods by popular election; it was defeated following a speech by the praetor, Gaius Laelius Sapiens.[46][47]

- Gaius Licinius (C. f. C. n.) Crassus, probably son of the tribune of 145 BC.[48]

- Licinia C. f. C. n., a Vestal Virgin in 123 BC.

- Publius Licinius P. f. P. n. Crassus Dives Mucianus, consul in 131 BC. He was the son of Publius Mucius Scaevola, the consul of 175 BC, but was adopted by his uncle, Publius Licinius Crassus, consul in 171.

- Marcus Licinius P. f. P. n. Crassus Agelastus, grandfather of the triumvir, he was said to have obtained his surname because he never laughed.[49][50]

- Licinia P. f. P. n., sister of Marcus Licinius Crassus Agelastus.

- Licinia P. f. P. n., daughter of Publius Licinius Crassus Mucianus, married Gaius Sulpicius Galba, son of the orator Servius Sulpicius Galba.

- Licinia P. f. P. n., daughter of Publius Licinius Crassus Mucianus, married Gaius Gracchus, the tribune.

- Publius Licinius M. f. P. n. Crassus, father of the triumvir, was consul in 97 BC, and triumphed over the Lusitani.

- Lucius Licinius L. f. Crassus, the greatest orator of his day, was consul in 95 BC, and censor in 92.

- Licinia L. f. L. n., daughter of the consul of 95 BC, married Publius Cornelius Scipio Nasica, praetor in 94 BC.

- Licinia L. f. L. n., daughter of the consul of 95 BC, married the younger Gaius Marius, consul in 82 BC.

- Lucius Licinius Crassus Scipio, grandson of the consul of 95 BC, was the son of Publius Cornelius Scipio Nasica and Licinia, and was adopted by his grandfather, who had no sons of his own. His brother was Quintus Caecilius Metellus Scipio.[51][52]

- Publius Licinius P. f. M. n. Crassus, brother of the triumvir, he died shortly before or during the Social War (91–88 BC).

- Lucius (?) Licinius P. f. M. n. Crassus, a brother of the triumvir who died in the massacre of 87 BC.[53] [54][55][56]

- Marcus Licinius P. f. M. n. Crassus, the triumvir, was consul in 70 and 55 BC, and censor in 65.

- Publius Licinius P. f. P. n. Crassus, a nephew of the triumvir, squandered his fortune.[57]

- Licinius Crassus Dives, praetor in 59 BC, was perhaps the same as Publius Licinius Crassus, nephew of the triumvir.[58][59]

- Publius Licinius Crassus Dives, praetor in 57 BC, favored Cicero's return from exile.[60]

- Publius Licinius P. f. Crassus Junianus Damasippus,[lower-roman 4] tribune of the plebs in 53 BC, and a friend of Cicero. During the Civil War he was a partisan of Pompeius, and fought under Metellus Scipio in Africa. While escaping after the Battle of Thapsus, his ship was sunk by Caesar's fleet, and he drowned alongside Scipio and others.[66][63][64][65]

- Licinius P. f. P. n. Crassus Damasippus, a contemporary of Cicero, who wrote of his intention to purchase a garden from him in 45 BC. He was a dealer in statuary, and went bankrupt, but was prevented from doing away with himself by the Stoic Stertinius. He was undoubtedly a son of the tribune in 53 BC.[67][68][69]

- Lucius Licinius (P. f. P. n.) Crassus Damasippus, mentioned in a late Republican inscription from Rome, was probably either the statuary, or his brother, since the elder Damasippus had at least two children, who were pardoned by Caesar after their father's death, and allowed to inherit his property.[70][71]

- Marcus Licinius M. f. P. n. Crassus, elder son of the triumvir, was Caesar's quaestor in Gaul, and prefect of Gallia Cisalpina at the beginning of the Civil War in 49 BC.[72][73][74]

- Publius Licinius M. f. P. n. Crassus, younger son of the triumvir, he was Caesar's legate in Gaul from 58 to 55 BC. He accompanied his father to Syria, and died at the Battle of Carrhae in 53.

- Marcus Licinius M. f. M. n. Crassus, consul in 30 BC with Octavian. In the following year, as proconsul of Macedonia, he fought successfully against the surrounding barbarians.[75]

- Marcus Licinius M. f. M. n. Crassus Dives, consul in 14 BC.[76]

- Marcus Licinius Crassus Frugi, consul in AD 27.

- Marcus Licinius M. f. Crassus, son Marcus Licinius Crassus Frugi, he was slain by the emperor Nero.

- Licinius Crassus Scribonianus, son of Marcus Licinius Crassus Frugi, he was offered the empire by Marcus Antonius Primus, but refused.[77]

- Lucius Calpurnius Piso Licinianus, son of Marcus Licinius Crassus Frugi, he was adopted as the heir of Galba, but slain by the soldiers of Otho in AD 69.

- Licinius M. f. Crassus (Frugi?), son of Marcus Licinius Crassus Frugi with Scribonia, he changed his name after his mother's ancestor Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus. Husband of Claudius' daughter, Claudia Antonia, Pompeius was later murdered in 41.[78]

- Marcus Licinius Crassus Mucianus, consul for the first time circa AD 63, and again in 70 and 72, was the general and chief advisor of Vespasian.

Licinii Luculli

- Lucius Licinius Lucullus, curule aedile in 202 BC, he and his colleague distinguished themselves by the magnificence with which they exhibited the Ludi Romani, but were suspected of having allowed their subordinates to defraud the public treasury.[79]

- Gaius Licinius Lucullus, tribunus plebis in 196 BC, he proposed the establishment of the tresviri epulones, and was one of the first three persons appointed to the new office.[80]

- Marcus Licinius Lucullus, praetor peregrinus in 186 BC, he and his colleagues were compelled to suspend all judicial proceedings for thirty days, in consequence of the alarm caused by the discovery of the cult of Bacchus at Rome.[81]

- Lucius Licinius (L. f.) Lucullus, consul in 151 BC, he was assigned to Hispania, where he instigated a war against the Vaccaei, and as proconsul the following year, carried on war against the Lusitani with acts of great perfidy and cruelty.

- Publius Licinius Lucullus, tribunus plebis in 110 BC, attempted, together with his colleague, Lucius Annius, to procure their joint re-election, but this was opposed by the other tribunes, and the election of all of the annual magistrates was postponed.[82]

- Lucius Licinius L. f. (L. n.) Lucullus, praetor in 104 BC, appointed by the senate to the command in Sicily during the Second Servile War; victorious in the field, he was unable to capture the stronghold of the slaves, and surrendered his command, but not before destroying his camp and supplies out of spite.

- Lucius Licinius L. f. L. n. Lucullus, consul in 74 BC, the conqueror of Mithridates, over whom he triumphed in 63. He was famous for his wealth and his luxurious lifestyle, gardens, and villa.

- Marcus Licinius L. f. L. n. Lucullus, he was adopted into the gens Terentia as Marcus Terentius M. f. Varro Lucullus, consul in 73 BC, and triumphed in 71.

- Lucius Licinius Lucullus, praetor in 67 BC, a man famous for his moderation and mildness of disposition; Dionysius records a colorful anecdote about his restraint in the face of insult.[83]

- Gnaeus Licinius Lucullus, a friend of Cicero, who attended the funeral of Lucullus' mother.[84]

- Lucius Licinius L. f. L. n. Lucullus, son of the consul of 74 BC, he was raised by his uncle, Cato, and Cicero. He espoused the cause of Brutus and Cassius, and was killed in the retreat from the Battle of Philippi, in 42 BC.[85][86][87]

Licinii Nervae

- Gaius Licinius Nerva, praetor in 167 BC, assigned the province of Hispania Ulterior.[88]

- Gaius Licinius C. f. Nerva, perhaps son of the praetor of 167; one of the legates who reported the conquest of Illyricum in 168; the following year he was one of the commissioners to return the Thracian hostages.[89]

- Aulus Licinius Nerva, praetor in 166 BC; he was assigned to Hispania.[89]

- Aulus Licinius (A. f.) Nerva, praetor, probably in 143 BC; the following year he was governor of Macedonia, and his quaestor, Lucius Tremellius Scrofa, defeated the army of a pretender.[90][91]

- Publius Licinius Nerva, propraetor in Sicily in 104 BC, his dealings with the Publicani and their slaves led to the commencement of the Second Servile War. Nerva was succeeded by his relative, Lucius Licinius Lucullus.[92]

- Gaius Licinius Nerva, described by Cicero as a bad but eloquent man, in contrast with Lucius Calpurnius Bestia, tribunus plebis in 62 BC and one of Catiline's conspirators.[93]

- Licinius Nerva, quaestor of Decimus Junius Brutus in the war before Mutina.[94]

- Aulus Licinius Nerva Silianus, consul in AD 7, was the son of Publius Silius, consul in 20 BC, but was adopted into the family of the Licinii Nervae.[95][96]

Licinii Sacerdotes

- Gaius Licinius Sacerdos, an eques, who appeared before Scipio Aemilianus, during his censorship in 142 BC. Scipio accused him of perjury, but as no witnesses came forward, Licinius was dismissed.[97][98]

- Gaius Licinius C. f. Sacerdos, praetor urbanus in 75 BC; in the following year he had the government of Sicily, in which he was succeeded by Verres. Cicero contrasts his upright administration with the corruption of his successor.[99][100][101]

Licinii Murenae

- Lucius Licinius Murena, triumvir monetalis between 169 and 158 BC, praetor in 147, and legate of Lucius Mummius Achaicus in Greece from 146 to 145.[102][103]

- Lucius Licinius L. f. Murena, praetor before 101 BC. He was a contemporary of the orator Lucius Licinius Crassus, who was consul in 95 BC.[102][22][104]

- Publius Licinius L. f. L. n. Murena, described by Cicero as a man of moderate talent, and some literary knowledge, who devoted much attention to the study of antiquity. He died in the civil war between Sulla and the younger Marius, about 82 BC.[105]

- Lucius Licinius L. f. L. n. Murena, one of Sulla's lieutenants in Greece, he later fought against Mithridates without authorization, and was recalled by Sulla in 81 BC. He had probably been praetor about 88. He was awarded a triumph in 81.[106][107][108][109]

- Lucius Licinius L. f. L. n. Murena, elected consul in 62 BC; before entering office he was accused of bribery, and defended by Quintus Hortensius, Cicero, and Marcus Licinius Crassus. During his consulship he worked to preserve the peace in the aftermath of Catiline's conspiracy.[110]

- Gaius Licinius L. f. L. n. Murena, legate of his brother, the consul of 62, in Gallia Cisalpina; he captured some of Catiline's allies. He was also aedile circa 59.[111][112]

- Licinius (L. f. L. n.) Murena, probably the son of the consul of 62, he was adopted by Aulus Terentius Varro, and assumed the name Aulus Terentius Varro Murena. He was consul suffectus in 23 BC, but the following year conspired with Fannius Caepio and was put to death.[113][114][115]

- Lucius Licinius Varro Murena, one of the conspirators against Augustus, was the adopted brother of Aulus, consul in 23 BC.[116]

Licinii Macri

- Gaius Licinius Macer, praetor in 68 BC, he was impeached for extortion by Cicero in 66, he took his own life to avoid the disgrace of a public condemnation. He was probably the annalist Licinius Macer, frequently mentioned by Livius and other historians.

- Gaius Licinius C. f. Macer Calvus, a renowned orator and poet, favorably compared with Cicero and Catullus.

Others

- Publius Licinius Tegula, the author of a religious poem, sung by the Roman virgins in 200 BC.[117]

- Gaius Licinius C. f., a senator in 129 BC.[118]

- Licinius, an educated slave belonging to Gaius Sempronius Gracchus, who, according to a well-known story, used to stand behind his master with a musical instrument, in order to moderate Gracchus' tone when he was speaking. He afterward became a client of Quintus Lutatius Catulus.[119][120][121]

- Gaius Licinius P. f. Geta, consul in 116 BC, was expelled from the senate with thirty-one others by the censors of 115; he was subsequently restored to his rank, and himself held the office of censor in 108.[122][123][124]

- Sextus Licinius, a senator, whom Gaius Marius ordered to be hurled from the Tarpeian Rock, on the day that he entered upon his seventh consulship, the first of January, 86 BC.[125][126][127]

- Gaius Licinius C. f., a senator in 73 BC, had been praetor in an uncertain year. He was probably not related to the Gaius Licinius who was a senator in 129, since he belonged to the tribus Pomptina, while the senator of 129 was from Terentina.[99][128]

- Aulus Licinius Archias, a Greek poet, defended by Cicero on a charge of illegally assuming Roman citizenship in 61 BC.

- Lucius Licinius Squillus, one of the conspirators against Quintus Cassius Longinus in Hispania, in 48 BC.

- Licinius Lenticula, a companion of Marcus Antonius, who restored him to his former status, after Lenticula had been condemned for gambling.[129][130]

- Licinius Regulus, a senator who lost his seat when the senate was re-organized by Augustus.[131]

- Publius Licinius Stolo, triumvir monetalis during the reign of Augustus.

- Gaius Licinius Imbrex, a Latin comic poet, quoted by Aulus Gellius and Sextus Pompeius Festus.[132][133]

- Licinius Lartius, praetor in Hispania, and later governor of one of the imperial provinces. He was a contemporary of the elder Plinius.[134][135][136]

- Licinius Caecina, a senator attached to the party of Otho in AD 69; he may be the same as the Licinius Caecina of praetorian rank mentioned by the elder Pliny.[137][138]

- Licinius Proculus, a friend of Otho, who raised him to the rank of praefectus praetorio. His bad advice and lack of military experience hastened Otho's downfall. He was pardoned by Vitellius.[139]

- Licinius Nepos, described by the younger Plinius as an upright but severe man; he was praetor, although the year is uncertain.[140]

- Lucius Licinius Sura, consul suffectus ex kal. Jul. possibly around AD 93, and consul in 102 and 107.[141]

- Quintus Licinius Nepos, consul suffectus at some undetermined point during the reign of Septimus Severus.[142]

- Licinius Rufinus, a jurist in the time of Alexander Severus; he compiled twelve books of Regulae.[143][144]

- Marcus Gnaeus Licinius Rufinus, imperial amicus of the first half of the third century.[145]

- Publius Licinius Valerianus, emperor from AD 253 to 260.

- Publius Licinius Egnatius Gallienus, emperor from AD 253 to 268.

- Publius Flavius Galerius Valerius Licinianus Licinius, emperor from AD 307 to 324.

- Flavius Valerius Licinianus Licinius, son of the emperor Licinius, he was put to death in AD 323, when he was about eight years old.

Footnotes

- The Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology lists this Licinius as consular tribune in 377 or 378 B.C. based on Livy, vi. 31. 377 appears to be an error in the text, as 378 appears in the chronology in the appendix. This identification may have been based on Livius' identification of Licinius Menenius as the tribune of that year. Menenius, whose name is given variously as Licinus or Lucius, is elsewhere accepted as by the same source as consular tribune in 378; thus the year that Licinius Calvus was consular tribune remains uncertain.[10]

- Both the Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology and Broughton, following Livy, agree that Plutarch and Cassius Dio are mistaken in identifying this Gaius Licinius Calvus with Gaius Licinius Calvus Stolo, tribune of the plebs in the same year.[10][37]

- The Fasti Capitolini state that Calvus was consul in 364, and Stolo in 361; but Livy, Valerius Maximus, and Plutarch all state that Stolo was consul in 364, and Calvus in 361. The Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology supposes that Stolo was consul in both years. Both Calvus and Stolo had good claims to the consulship, the first having served as magister equitum in 368, the other having brought forward the law permitting the election of plebeian consuls.[10][40]

- So called in an inscription, but without the surname "Damasippus".[61] Men named "Publius Crassus Junianus", "Licinius Damasippus" and "Crassus" are described by different sources in similar roles in Africa during the Civil War.[62][63][64] These have all been shown to be the same person. He was a son of Lucius Junius Brutus Damasippus, whose praenomen he probably shared, until his adoption by Publius Licinius Crassus Dives, the praetor of 57 BC.[65]

See also

References

- This Publius Licinius Crassus is probably the father of the triumvir, but has also been conjectured to be his son. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, William Smith, Editor.

- Drumann, Geschichte Roms.

- Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, vol. II, p. 782 ("Licinia Gens").

- Chase, p. 109.

- Lanzi, vol. II, p. 342.

- Livy, vii. 2.

- Chase, p. 110

- Chase, pp. 113, 114.

- Chase, pp. 112 (Stola), 113 (Stolo).

- Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, vol. I, p. 586 ("Calvus").

- Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, vol. I, p. 586 ("Calvus", "Gaius Licinius Macer Calvus").

- Cassell's Latin and English Dictionary.

- Chase, p. 111.

- Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, vol. I, pp. 872, 873 ("Crassus").

- Marshall, "Crassus and the Cognomen Dives."

- Drumann, vol. IV, pp. 71–115.

- Chase, p. 113.

- Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, vol. II, pp. 830, 831 ("Lucullus").

- Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia, ix. 54.

- Macrobius, Saturnalia, ii. 11.

- Drumann, vol. IV, p. 183 ff.

- Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, vol. II, p. 1121 ("Murena").

- The New College Latin & English Dictionary, "Geta".

- Chase, pp. 111, 112.

- The New College Latin & English Dictionary, "sacerdos".

- Livy|, ii. 33.

- Dionysius, vi. 89.

- Livy, ii. 43.

- Dionysius, ix. 1.

- Livy, v. 12.

- Realencyclopädie der Classischen Altertumswissenschaft, "Licinius" no. 43.

- Mommsen, Römische Forschungen, vol. I, p. 95.

- Livy, v. 18.

- Diodorus Siculus, xiv. 90.

- The Fasti Capitolini mention only the father, elected for the second time.

- Broughton, vol. I, pp. 87, 88.

- Broughton, vol. I, pp. 112, 113.

- Titus Livius, Ab Urbe Condita, vi. 39.

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica, xiv. 57.

- Broughton, vol. I, pp. 116, 118, 119.

- Zonaras, viii. 18, p. 400.

- Livy, xxi. 18, Epitome, 50.

- Livy, xxvii. 22, 23, 51.

- Livy, xli, xlii, xliii.

- Livy, xli. 22, xlv. 17.

- Cicero, Laelius de Amicitia, 25; Brutus, 21.

- Varro, Rerum Rusticarum, i. 2.

- Cassius Dio, fragmentum xcii.

- Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia, vii. 18.

- Cicero, De Finibus, v. 30.

- Cicero, Brutus, 58.

- Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia, xxxiv. 3. s. 8.

- Plutarch, "The Life of Crassus", 1, 4.

- Cicero, Epistulae ad Atticum, xii. 24.

- Florus, iii. 21. § 14.

- Appian, Bellum Civile, i. p. 394.

- Valerius Maximus, vi. 9. § 12.

- Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, vol. I, pp. 381, 382 ("Crassus", no. 27).

- Cicero, Epistulae ad Atticum, ii. 24. § 2.

- Cicero, Post Reditum in Senatu, 9.

- Verboven, "Damasippus", p. 208.

- Crawford, p. 472, no. 460.

- Caesar, De Bello Civili, ii. 44; De Bello Africo, 96.

- Plutarch, "The Life of Cato the Younger" 70.

- Verboven, "Damasippus", pp. 197, 198.

- Cicero, Epistulae ad Quintum Fratrem, iii. 8. § 3.

- Cicero, Epistulae ad Familiares, vii. 23; Epistulae ad Atticum, xii. 29, 33.

- Horace Satirae, ii. 3, 16, 64.

- Verboven, "Damasippus", pp. 195, 198, 199

- CIL VI, 22930.

- Verboven, "Damasippus", p. 198 (and Note 7).

- Cicero, Epistulae ad Familiares, v. 8.

- Caesar, De Bello Gallico, v. 24.

- Justin, xlii. 4.

- Livy, Epitome, cxxxiv, cxxxv.

- Cassius Dio, liv. 24.

- Tacitus, Historiae, i. 47, iv. 39.

- Suetonius, "The Life of Caligula"; "The Life of Claudius."

- Livy, xxx. 39.

- Livy, xxxiii. 42, xxxvi. 36.

- Livy, xxxix. 6, 8, 18.

- Sallust Bellum Jugurthinum, 37.

- Dionysius, xxxvi. 24.

- Cicero, Epistulae ad Atticum, xv. 1.

- Cicero, De Finibus, iii. 2; Epistulae ad Atticum, xiii. 6; Philippicae, x. 4.

- Velleius Paterculus, ii. 71.

- Valerius Maximus, iv. 7. § 4.

- Livy, xlv. 16.

- Livy, xlv. 3, 42.

- Livy, Epitome, 53.

- Eutropius, iv. 15.

- Diodorus Siculus, xxxvi.

- Cicero, Brutus, 34.

- Drumann, vol. IV. p. 19 (no. 85).

- Velleius Paterculus ii. 116.

- Cassius Dio, lv. 30.

- Cicero, Pro Cluentio, 48.

- Valerius Maximus, iv. 1. § 10.

- SIG, 747.

- Cicero, In Verrem, i. 10, 46, 50, ii. 28, iii. 50, 92, Pro Plancio, 11.

- Asconius, in Toga Candida, p. 83 (ed. Orelli).

- Cicero, Pro Murena, 15

- Broughton, vol. I, pp. 463, 467, 468.

- Broughton, vol. I, p. 571.

- Cicero, Brutus, 54, 90.

- Memnon, Heracleia, 26.

- Appian, Mithridatic War, 32, 64-66, 93.

- SIG, 745.

- Broughton, vol. II, pp. 40, 50, 61, 62, 77, 129.

- Broughton, vol. II, pp. 103, 109 (note 5), 134, 163, 169, 172, 173, 484.

- Sallust, Bellum Catilinae, 42.

- Broughton, vol. II, p. 170, 189, 193 (note 4).

- Vitruvius, de Architectura, II, 8 § 9.

- Horace, Carmen Saeculare, ii. 2, 10.

- Cassius Dio, liii. 25, liv. 3.

- Ando, p. 140.

- Livy, xxxi. 12.

- Sherk, "Senatus Consultum De Agro Pergameno", p. 367.

- Plutarch, "The Life of Tiberius Gracchus", 2.

- Cicero, De Oratore, iii. 60.

- Aulus Gellius, i. 11.

- Cicero, Pro Cluentio, 42.

- Valerius Maximus, ii. 9. § 9.

- Broughton, vol. I, p. 530.

- Livy, Epitome, 80.

- Plutarch, "The Life of Marius", 45.

- Cassius Dio, fragmentum 120.

- Broughton, vol. 2, p. 579.

- Cicero, Philippicae, ii. 23.

- Cassius Dio, xlv. 47.

- Cassius Dio, liv. 14.

- Festus, s. vv. Imbrex, Obstitum.

- Aulus Gellius, xiii. 22, xv. 24.

- Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia, xix. 2. s. 11, xxxi. 2. s. 18.

- Pliny the Younger, Epistulae, ii. 14, iii. 5.

- Gruter, p. 180.

- Tacitus, Historiae, ii. 53.

- Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia, xx. 18. s. 76.

- Tacitus, Historiae, i. 46, 82, 87, ii. 33, 39, 44, 60.

- Pliny the Younger, Epistulae, iv. 29, v. 4, 21, vi. 5.

- Eck and Pangerl, "Zwei Konstitutionen für die Truppen Niedermösiens".

- Paul M. M. Leunissen, Konsuln und Konsulare in der Zeit von Commodus bis Severus Alexander (Amsterdam: Verlag Gieben, 1989), pp. 149f

- Digesta seu Pandectae, 40. tit. 13. s. 4.

- Zimmern, vol. I.

- Fergus Millar, "The Greek East and Roman Law: The Dossier of M. Cn. Licinius Rufinus", Journal of Roman Studies, 89 (1999), pp. 90-108

Bibliography

- Marcus Tullius Cicero, Laelius sive de Amicitia, Brutus, De Finibus Bonorum et Malorum, Epistulae ad Atticum, Post Reditum in Senatu, Epistulae ad Quintum Fratrem, Epistulae ad Familiares, Philippicae, Pro Cluentio, Pro Murena, De Oratore, In Verrem, Pro Plancio.

- Gaius Julius Caesar, Commentarii de Bello Gallico (Commentaries on the Gallic War), Commentarii de Bello Civili (Commentaries on the Civil War), De Bello Africo (On the African War [attributed]).

- Gaius Sallustius Crispus, Bellum Catilinae (The Conspiracy of Catiline), Bellum Jugurthinum (The Jugurthine War).

- Marcus Terentius Varro, Rerum Rusticarum (Rural Matters).

- Marcus Vitruvius Pollio (Vitruvius), de Architectura (On architecture).

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica (Library of History).

- Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Romaike Archaiologia.

- Titus Livius (Livy), Ab Urbe Condita (History of Rome).

- Quintus Horatius Flaccus (Horace), Satirae (Satires), Carmen Saeculare.

- Marcus Velleius Paterculus, Compendium of Roman History.

- Memnon, History of Heracleia.

- Valerius Maximus, Factorum ac Dictorum Memorabilium (Memorable Facts and Sayings).

- Quintus Asconius Pedianus, Commentarius in Oratio Ciceronis In Toga Candida (Commentary on Cicero's Oration In Toga Candida).

- Gaius Plinius Secundus (Pliny the Elder), Naturalis Historia (Natural History).

- Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus (Pliny the Younger), Epistulae (Letters).

- Publius Cornelius Tacitus, Historiae.

- Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus, De Vita Caesarum (Lives of the Caesars, or The Twelve Caesars).

- Plutarchus, Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans.

- Lucius Annaeus Florus, Epitome de T. Livio Bellorum Omnium Annorum DCC (Epitome of Livy: All the Wars of Seven Hundred Years).

- Appianus Alexandrinus (Appian), Bellum Civile (The Civil War), Bella Mithridatica (The Mithridatic Wars).

- Marcus Junianus Justinus (Justin), Epitome de Cn. Pompeio Trogo Historiarum Philippicarum et Totius Mundi Originum et Terrae Situs (Epitome of Trogus' "Philippic History and Origin of the Whole World and all of its Places").

- Aulus Gellius, Noctes Atticae (Attic Nights).

- Sextus Pompeius Festus, Epitome de M. Verrio Flacco de Verborum Significatu (Epitome of Marcus Verrius Flaccus: On the Meaning of Words).

- Lucius Cassius Dio Cocceianus (Cassius Dio), Roman History.

- Eutropius, Breviarium Historiae Romanae (Abridgement of the History of Rome).

- Ambrosius Theodosius Macrobius, Saturnalia.

- Digesta seu Pandectae (The Digest).

- Joannes Zonaras, Epitome Historiarum (Epitome of History).

- Jan Gruter, Inscriptiones Antiquae Totius Orbis Romani, Heidelberg (1603).

- Luigi Lanzi, Saggio di Lingua Etrusca, Rome (1789).

- Sigmund Wilhelm Zimmern, Geschichte des Römischen Privatrechts bis Justinian (History of Roman Private Law to Justinian), J. C. B. Mohr, Heidelberg (1826).

- Wilhelm Drumann, Geschichte Roms in seinem Übergang von der republikanischen zur monarchischen Verfassung, oder: Pompeius, Caesar, Cicero und ihre Zeitgenossen, Königsberg (1834–1844).

- "Licinia Gens" in the Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, William Smith, ed., Little, Brown and Company, Boston (1849).

- Christian Matthias Theodor Mommsen, Römische Forschungen (Roman Research), Weidmannsche Buchhandlung, Berlin (1864–1879).

- Wilhelm Dittenberger, Sylloge Inscriptionum Graecarum (Collection of Greek Inscriptions, abbreviated SIG), Leipzig (1883).

- August Pauly, Georg Wissowa, et alii, Realencyclopädie der Classischen Altertumswissenschaft, J. B. Metzler, Stuttgart (1894–1980).

- George Davis Chase, "The Origin of Roman Praenomina", in Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, vol. VIII (1897).

- T. Robert S. Broughton, The Magistrates of the Roman Republic, American Philological Association (1952).

- D.P. Simpson, Cassell's Latin and English Dictionary, Macmillan Publishing Company, New York (1963).

- Robert K. Sherk, "The Text of the Senatus Consultum De Agro Pergameno", in Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies, vol. 7, pp. 361–369 (1966).

- Bruce A. Marshall, "Crassus and the Cognomen Dives," in Historia, vol. 22 (1973), pp. 459–467.

- John C. Traupman, The New College Latin & English Dictionary, Bantam Books, New York (1995).

- Koenraad Verboven, "Damasippus, the Story of a Businessman?", in Studies in Latin Literature and Roman History VIII, Carl Deroux, ed., Collection Latomus, vol. 239 Brussels (1997), ISBN 2-87031-179-6, pp. 195–217.

- Clifford Ando, Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire, University of California Press (2000).

- Werner Eck and Andreas Pangerl, "Zwei Konstitutionen für die Truppen Niedermösiens vom 9. September 97", in Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, vol. 151, pp. 185–192 (2005).

![]()