Lambri

Lamuri or Lambri[1] was a kingdom in northern Sumatra, Indonesia from the Srivijaya period until the early 16th century. The area was inhabited by Hindu population around the seventh century.[2] There is also evidence of Buddhism.[3] The region is also thought to be one of the earliest places of arrival of Islam in the Indonesian archipelago, and in its later period its rulers were Muslims.

Lambri is generally considered to be located in the Aceh province near Banda Aceh. Its location has been suggested to be in today's Lambaro to the west of Bandar Aceh where submerged ruins of buildings and tombstones have been found,[1] although some now associate Lambri with Lam Reh where there are ancient tombstones.[4] Accounts of Lambri have been given in various sources from the 9th century onwards, and it is thought to have become absorbed into the Aceh Sultanate by the early 16th century.

Names

The Kingdom of Lamuri or Lambri was known to the Arabs from the 9th century onward, and named as Rām(n)ī (رامني), Lawrī, Lāmurī and other variants.[5] The only mention of the kingdom in Indian sources appears in the Tanjore inscription of 1030 which named it as Ilâmurideśam in Tamil.[5] In Chinese records, it was first referred to as Lanli (藍里) in Lingwai Daida by Zhou Qufei in 1178, later Lanwuli (藍無里) in Zhu Fan Zhi, Nanwuli (喃![]()

In the Javanese work of 1365 Nagarakretagama, it is named Lamuri, and in the Malay Annals, Lambri.[5] In Acehnese, the word lam means "in", "inside" or "deep", and it is also used as a prefix for many settlements around the Aceh area.[1]

Historical accounts

The first mention of Lamuri may be in the 9th century by the Arab geographer Ibn Khurdadhbih who wrote: "Beyond Serandib is the isle of Ram(n)i, where the rhinoceros can be seen. ... This island produces bamboo and brazilwood, the roots of which are antidote for deadly poisons. ... This country produces tall camphor trees." According to Akhbar al-Sin wa'l Hind (An Account of China and India), Ramni "produces numerous elephants as well as brazilwood and bamboos. The island is washed by two seas ... Harkand and that of Salahit."[1][8] In the 10th century Al-Masudi wrote that Ramin (i.e. Lamuri) was "well populated and governed by kings. They are full of gold mines, and nearby is the land of Fansur, whence is derived the fansuri camphor, which is only found there in large quantities in the years that have many storms and earthquakes".[1]

Chinese historical records indicate that ancient Lamuri was used as a staging post for traders waiting out the winter monsoon for favourable winds to take them westwards to Sri Lanka, India and the Arab world. Zhao Rugua in Zhu Fan Zhi said that the products of Lan-wu-li (Lamuri) were sappanwood, elephant tusks, and white rattan, and that its people were "warlike and often use poison arrows".[9] In the 14th century, Wang Dayuan noted in Daoyi Zhilüe there were "mountain-like waves" crashing against it, and that the natives lived on the hills and were given to piracy.[1] He also noted that it produced the best-quality lakawood, and later records showed that its king presented the product to the Chinese emperor as tribute during the Ming dynasty.[6]

Lambri was also mentioned by early century European travellers Marco Polo and Odoric of Pordenone.[10] Polo wrote that there were men with tails in this kingdom of Lambri. The tails were a palm in length with the thickness of a dog's tail and hairless.[11] In 1783, Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, Comte de Mirabeau briefly mentions Lambri men with tails citing an earlier work from 1566, and that men with tails brought back by missionaries had elongated coccyx.[12] According to Odoric of Pordenone, whose early 14th century account of Lamori was borrowed by Sir John Mandeville's in his Book of Marvels and Travels, Lamori was a very hot country, so both men and women went about naked. He mentioned that all women were shared in common, and no one was any person's husband or wife. Similarly the whole of the land was held in common, although they had their own individual houses. They were also said to be cannibals, who purchased children from merchants to slaughter them.[13][14]

Marco Polo noted that the people were "idolators" when he passed through in the late 13th century.[11] However, it has been argued that the inscriptions on tombstone of Sultan Sulaiman bin Abdullah al-Basr at Lam Reh may be the first documented royal conversion to Islam in the region. The inscriptions has been dated to 1211 although a later date had also been proposed. Some thought that Islam may have arrived in the area as early as the 8th century.[15] By the early 15th century when Zheng He's voyages passed through Lamuri, the ruler of Lamuri was said to profess the Islamic faith, and that its estimated population of over 1,000 families were all Muslims, according to Yingya Shenglan written by Ma Huan who was in Zheng He's fleet.[16][17]

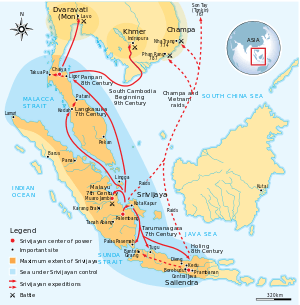

Lamuri is thought to be one of the cities controlled by the Srivijaya empire. In 1025, the port was attacked in the raids on Srivijaya led by Rajendra Chola, and Lamuri appeared to have come under the influence of the Tamils. By the 13th century, it was again under Srivijayan control as Zhu Fan Zhi noted that it paid tribute to Sanfoqi (usually thought to be Srivijaya). Marco Polo noted in 1292 that it had pledged its allegiance to Kublai Khan (the Mongols had demanded the submission of various states that year before their failed invasion of Java).[10] In the 14th century, Odoric of Pordenone mentioned that Lamori and Samudera were constantly at war with each other.[18] The 14th century work Nagarakretagama listed Lamuri as one of the vassal states of the Majapahit. Portuguese writers such as João de Barros also mentioned Lambri in the 16th century; de Barros placed Lambrij (Lamuri) between Daya and Achin (Aceh),[19] but according to Suma Oriental written by Tomé Pires in 1512–1515, Lambry had by then come under the control of Achin whose king was the only ruler in the area.[20]

See also

References

- E. Edwards McKinnon (October 1988). "Beyond Serandib: A Note on Lambri at the Northern Tip of Aceh". Indonesia. 46: 102–121. doi:10.2307/3351047. hdl:1813/53892.

- "Indra Patra Fortress". Indonesia Tourism.

- "Situs Lamuri Dipetakan". Banda Aceh Tourism. 28 September 2014.

- Suprayitno (2011). "Evidence of the Beginning of Islam in Sumatera: Study on the Acehnese Tombstone" (PDF). TAWARIKH: International Journal for Historical Studies. 2 (2). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-28.

- H.K.J. Cowan (1933). "LAMURI — LAMBRI — LAWRI — RAM(N)I — LAN-LI — LAN-WU-LI — NAN-PO-LI". Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia. 90 (1): 422–424. doi:10.1163/22134379-90001421.

- Derek Heng Thiam Soon (June 2001). "The Trade in Lakawood Products between South China and the Malay World from the Twelfth to Fifteenth Centuries AD". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 32 (2): 133–149. doi:10.1017/s0022463401000066. JSTOR 20072321.

- J.M. Dent (1908), "Chapter 36: Of the Town of Lop Of the Desert in its Vicinity - And of the strange Noises heard by those who pass over the latter", The travels of Marco Polo the Venetian, p. 344

- Thomas Suarez. Early Mapping of Southeast Asia: The Epic Story of Seafarers, Adventurers and Cartographers Who First Mapped the Regions Between China and India. Periplus Editions. ISBN 9781462906963.

- Friedrich Hirth, William Woodville Rockhill. Chau Ju-kua: His Work On The Chinese And Arab Trade In The Twelfth And Thirteenth Centuries, Entitled Chu-fan-chï. pp. 72–74.

- John Norman Miksic, Goh Geok Yian. Ancient Southeast Asia. Routledge. ISBN 9781317279037.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Marco Polo, Sir Henry Yule, Henri Cordier. The Travels of Marco Polo: The Complete Yule-Cordier Edition (New ed of 1903 ed.). Dover Publications Inc. p. 299. ISBN 978-0486275871.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Mirabeau, Honoré (1867). Erotika Biblion. Chevalier de Pierrugues. Chez tous les Libraries. p. 92.

- Sir Henry Yule (ed.). Cathay and the Way Thither: Being a Collection of Medieval Notices of China, Issue 36. pp. 84–86.

- Sir John Mandeville (2012). The Book of Marvels and Travels. Translated by Anthony Bale. Oxford University Press. pp. 78–79, 82. ISBN 978-0199600601.

- Geoffrey C. Gunn (1 August 2011). History Without Borders: The Making of an Asian World Region, 1000-1800. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 81, 83. ISBN 978-9888083343.

- Huan Ma, Chengjun Feng (2 December 1970). Survey of the Ocean's Shores' (1433). Cambridge University Press. pp. 47–48, 122–123. ISBN 978-0521010320.

- John Norman Miksic, Goh Geok Yian (31 October 2016). Ancient Southeast Asia. Routledge. ISBN 9780415735544.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Sir Henry Yule (ed.). Cathay and the Way Thither: Being a Collection of Medieval Notices of China, Issue 36. p. 86.

- Duarte Barbosa, Mansel Longworth Dames. Book of Duarte Barbosa, Volume 1. pp. 183–184. ISBN 978-8120604513.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Tomé Pires. The Suma oriental of Tome Pires, books 1-5. Asian Educational Services,India. p. 138. ISBN 978-8120605350.