Kingdom of Araucanía and Patagonia

The Kingdom of Araucanía and Patagonia (Spanish: Reino de la Araucanía y de la Patagonia; French: Royaume d'Araucanie et de Patagonie, sometimes referred to as New France) was an unrecognized state[1] proclaimed on November 17, 1860 by a decree of Orélie-Antoine de Tounens, a French lawyer and adventurer who claimed that the regions of Araucanía and eastern Patagonia did not need to depend on any other states. He had the support of some Mapuche lonkos around a small area in Araucanía, who were engaged in a desperate armed struggle to retain their independence in the face of hostile military and economic encroachment by the governments of Chile and Argentina, who coveted the Mapuche lands for economical and political reasons.

Kingdom of Araucanía and Patagonia Reino de la Araucanía y la Patagonia | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| November 17, 1860–January 5, 1862 | |||||||||||||

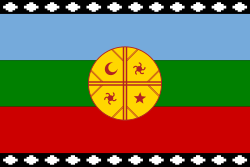

Flag

Coat of arms

| |||||||||||||

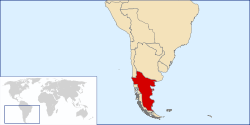

Location of the claimed territory of the Kingdom of Araucanía and Patagonia, in Chile and Argentina | |||||||||||||

| Status | Unrecognized state | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Perquenco, in current Cautín Province, La Araucanía Region, Chile | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Mapudungun | ||||||||||||

| Government | Elective monarchy | ||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||

• 1860–1878 | Orélie-Antoine I (Aurelio Antonio I) | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Occupation of the Araucanía | ||||||||||||

• Established | November 17, 1860 | ||||||||||||

• Disestablished | January 5, 1862 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||

Arrested on January 5, 1862 by the Chilean authorities, Antoine de Tounens was imprisoned and declared insane on September 2, 1862 by the court of Santiago[2] and expelled to France on October 28, 1862.[3] He later tried three times to return to Araucania to reclaim his "kingdom" without success.

History

In 1858, Antoine de Tounens, a former lawyer in Périgueux, France, who had read the book La Araucana by Alonso de Ercilla, decided to go to Araucania, inspired to become its king after reading the book. He landed at the port of Coquimbo in Chile and met some loncos (Mapuche tribal leaders) after arriving South to the Biobío. He promised them some arms and the help of France to maintain their independence from Chile. The Indians elected him Great Toqui, Supreme Chieftain of the Mapuches[4][5] possibly in the belief that their cause might be better served with a European acting on their behalf. On November 17, 1860, he proclaimed via a decree that the regions of Araucanía and eastern Patagonia did not need to depend on any other states and that the Kingdom of Araucania is founded with himself as King under the name Orélie-Antoine de Tounens. He declared Perquenco capital of his kingdom, created a flag, and had coins minted for the nation under the name of Nouvelle France.

The supposed founding of the Kingdom of Araucanía and Patagonia led to the Occupation of Araucanía by Chilean forces. Chilean president José Joaquín Pérez authorized Cornelio Saavedra Rodríguez, commander of the Chilean troops invading Araucanía to capture Antoine de Tounens on January 5, 1862. He was then imprisoned and declared insane on September 2, 1862, by the court of Santiago[2] and expelled to France on October 28, 1862.[3] Antoine later tried three times to return to Araucania to reclaim his "kingdom" without success.

On August 28, 1873, the Criminal Court of Paris ruled that Antoine de Tounens, first king of Araucania and Patagonia, did not justify his claim to the status of sovereignty.[6] He died in poverty on September 17, 1878, in Tourtoirac, France after years of fruitlessly struggling to regain his kingdom. Historians Simon Collier and William F. Sater describe the Kingdom of Araucanía as a "curious and semi-comic episode".[7]

According to travel writer Bruce Chatwin, the later history of the "kingdom" belongs rather to "the obsessions of bourgeois France than to the politics of South America."[8] A French champagne salesman, Gustave Laviarde, impressed by the story, decided to assume the vacant throne as Aquiles I.[9] He was appointed heir to the throne by Orélie-Antoine.[10] The pretenders to the throne of Araucania and Patagonia have been called monarchs and sovereigns of fantasy,[11][12][13][14][15] "having only fanciful claims to a kingdom without legal existence and having no international recognition".[16]

There does appear, however, to be increasing recognition of the role in defending Mapuche rights assumed by this "strange symbolic monarchy."[17][18] It has been reported that "the intensification of the Mapuche conflict in recent years has given a new purpose to the Kingdom of Araucania and Patagonia, long considered an absurdity by French society."[19]

Pretenders to the throne after Antoine de Tounens

Antoine de Tounens had no children, but since his death in 1878, some French citizens without any familial relations to him declared to be pretenders to the "throne of Araucania and Patagonia". Whether the Mapuche themselves accept this or are even aware of it, is unclear.[20]

- Achille Laviarde (1878–1902) also known as "Achille I"[21][22]

- Antoine-Hippolyte Cros (1902–1903) also known as "Antoine II"[21][23]

- Laure-Therese Cros (1903–1916) also known as "Laure Therese I"

- Jacques Antoine Bernard (1916–1952) also known as "Antoine III"

- Philippe Boiry (1952–2014) also known as "Prince Philippe"[23]

- Jean-Michel Parasiliti di Para (2014–2017) also known as "Antoine IV"

- Frédéric Luz (2017–) also known as "Frédéric I"

In popular culture

The 2017 film Rey is based on this incident.[24]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kingdom of Araucania and Patagonia. |

References

- Verónica Méndez Montero; Carolina Santelices Ariztía; Rodrigo Martínez Iturriaga (2009). Historia, Geografía y Ciencias Sociales 2° Educación Media (in Spanish). Santillana. ISBN 978-956-15-1557-4.

- Robert L. Scheina, Latin America's Wars: The age of the caudillo, 1791–1899, Brassey's, Incorporated, 2003, page 367.

- Jacques Lagrange, Le roi français d'Araucanie, PLB, 1990, page 11.

- Herbert Wendt, The Red, White, and Black Continent, Doubleday, 1966, page 271.

- Jean-François., Gareyte (2016). Le rêve du sorcier : Antoine de Tounens, roi d'Araucanie et de Patagonie : une biographie. Tome I. Mollier, Pierre. Périgueux: La Lauze. ISBN 9782352490524. OCLC 951666133.

- Le XIXe siècle : journal quotidien politique et littéraire. 1873.

- Collier, Simon; Sater, William F.: A history of Chile, 1808–2002. Cambridge University Press, 2004, ISBN 0-521-82749-3, p.96.

- Chatwin, Bruce: In Patagonia. Random House, 2012, ISBN 9781448105618, p. 25.

- Minnis, Natalie: Chile Insight. Langenscheidt Publishing, 2002, ISBN 981-234-890-5, p. 41.

- Nicholas Shakespeare, The Men who would be King, 1983.

- Fuligni, Bruno (1999). Politica Hermetica Les langues secrètes. L'Age d'homme. p. 135. ISBN 9782825113363.

- Journal du droit international privé et de la jurisprudence comparée. 1899. p. 910.

- Montaigu, Henri (1979). Histoire secrète de l'Aquitaine. A. Michel. p. 255. ISBN 9782226007520.

- Lavoix, Camille (2015). Argentine : Le tango des ambitions. Nevicata. ISBN 9782511040072.

- Bulletin de la Société de géographie de Lille. 1907. p. 150.

- Intermédiaire des chercheurs et curieux. ICC. 1972. p. 51.

- Marc Bassets, 'Federico I, un nieto de exiliado republicano en el "trono" de la Patagonia', El Pais, 1 June 2018, https://elpais.com/internacional/2018/05/31/mundo_global/1527781910_361229.html accessed 31 July 2019

- Baudouin Eschapasse, 'Querelle dynastique au royaume d'Araucanie', Le Point, 6 December 2018, https://www.lepoint.fr/monde/querelle-dynastique-au-royaume-d-araucanie-06-12-2018-2277162_24.php accessed 31 July 2019

- Mat Youkee, '"We are hostages": indigenous Mapuche accuse Chile and Argentina of genocide', The Guardian, 12 April 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/apr/12/indigenous-mapuche-accuse-chile-brazil-genocide accessed 31 July 2019

- Peregrine, Anthony (February 5, 2016). "France's forgotten monarchs". The Daily Telegraph.

- Piccirilli, R: "Diccionario histórico argentino", p. 260. Ediciones Historicas, 1953.

- Sociedad Chilena de Historia y Geografía, Archivo Nacional (Chile): "Revista chilena de historia y geografía", p. 277. Impr. Universitaria, 1931.

- Braun Menéndez, A: "Pequeña historia patagónica", p. 128. Emecé Editores, 1959.

- Clarke, Cath (January 5, 2018). "Rey review – dreamlike drama about a man who would be king". The Guardian. Retrieved February 3, 2019.

External links

- North American Araucanian Royalist Society

- Website of the Kingdom of Araucanía and Patagonia

- Kingdom of Araucania and Patagonia – Mapuche Portal