KZNE

KZNE (1150 AM) – branded The Zone 1150 AM – 93.7 FM – is a commercial sports radio station licensed to serve College Station, Texas. Owned by the Bryan Broadcasting Company, KZNE covers College Station, Bryan and much of the Brazos Valley.[1] The KZNE studios are located in College Station, while the station transmitter resides in Bryan. In addition to a standard analog transmission, KZNE is simulcast over low-power FM translator K229DK (93.7 FM) College Station, and is available online.

| |

| City | College Station, Texas |

|---|---|

| Broadcast area | Brazos Valley |

| Branding | The Zone 1150 AM & 93.7 FM |

| Slogan | Sports Radio |

| Frequency | 1150 kHz |

| Translator(s) | 93.7 K229DK (College Station) |

| First air date | October 7, 1922 (as WTAW at 1120 kHz) |

| Format | Sports |

| Power | 1,000 watts (day) 500 watts (night) |

| Class | B |

| Facility ID | 1150: 7632 93.7: 202366 |

| Transmitter coordinates | 30°38′05″N 96°21′20″W |

| Call sign meaning | K ZoNE (current branding) |

| Former call signs | WTAW (1922–2000) |

| Affiliations | CBS Sports Radio |

| Owner | Bryan Broadcasting Corporation (Bryan Broadcasting License Corporation) |

| Sister stations | KAGC, KNDE, KWBC, WTAW, WTAW-FM, KPWJ, KKEE |

| Webcast | Listen Live |

| Website | zone1150 |

History

5YA and 5XB

KZNE has its roots in experimental broadcasts in the late 1910s and early 1920s. At the Texas Agricultural College, licensed radio amateurs using telegraphic code operated on amateur radio frequencies. The names of participants with licensed station call signs and hometowns were as follows:

- Harry M. Saunders, 5NI – Greenville, Texas

- George E. Endress, 5JA/5ZAG – Austin, Texas

- W. Eugene Gray, 5QY – Austin, Texas

- J. Gordon Gray, 5QY – Austin, Texas

- Charles C. Clark, 5QA – Austin, Texas

- Franklin K. Matejka, 5RS – Caldwell, Texas

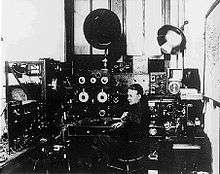

Shortly after the hostilities of World War I ended, amateur radio activities resumed. Students who had radio operating licenses were permitted to operate school stations. W. A. Tolson, Chief Operator at Texas A&M Experimental Station 5XB, and operators at University of Texas Experimental Station 5XU, decided to transmit the play-by-play of a Texas A&M Aggies football Thanksgiving football game from College Station.

At the time of the broadcast, the state of radio communications had not yet reached the point where vacuum tubes would be used in universal voice transmission. Instead, intelligence was commonly conveyed by dots and dashes using the International Morse radiotelegraph code. Transmissions by code are inherently much slower than by voice and its normal rate of speed is in the vicinity of 20 words or 100 characters per minute. This is too slow to keep up with gridiron activities and therefore, a system of abbreviations had to be devised. It so happened that Harry Saunders had previously worked as an operator with Western Union and was familiar with methods used by commercial telegraph companies in furnishing the play-by-play accounts of football and baseball games to newspapers, private sporting clubs, etc. When it was mentioned on the air to the operators at the University of Texas that such a list of abbreviations was being prepared, numerous requests for a copy of the list were received by radio and by mail from some of the 275 then licensed amateur radio operators in the state. Thus, what had started out to be a point-to-point broadcast, turned out to be one with many listeners.

For transmission, wires were run from the press box at Kyle Field to the station in the Electrical Engineering building a half-mile or so away. For reception, other wires were run to the home of a radio amateur who lived near the playing field. This arrangement enabled the operator to hear his own transmissions as well as those from amateur stations should their operators wish to interrupt for clarification or other information. The only radio equipment at the press box was a key for transmitting and a pair of headphones from receiving.

Although the reporting of play-by-play action in 1921 was simpler than that of today due to the absence of the two-platoon system and the lesser frequency of substitutions, it still required the help of spotters from each team to make it possible. The activity on the gridiron had to be put into abbreviations and then into radio signals. Actually, there was little delay in conveying the information to others and it is estimated that this delay rarely amounted to more than one play behind. Only one incident threatened the success of this broadcast. Near the end of the first half of the game a fuse blew out on the equipment, but this was hurriedly replaced by Tolson who went to the Electrical Engineering building after having been excused temporarily from his duty in the Aggie band. It is doubtful that Saunders, the sole operator in the press box, ever envisioned the magnitude of the chore that he had agreed to accept.

The situation at the University of Texas was relatively simple; and with the exception of more persons in the room and the addition of an audio amplifier and horn speaker, it could well have been the location of another radio amateur listener. The Gray brothers (now deceased), Clark and Endress manned the transmitter and receiver positions, copying the abbreviations sent from Kyle Field and on occasion, communicating with Saunders. Slips of paper with received abbreviations were passed over a long table to Matejka, who relayed the decoding over a horn speaker through an open window to the many interested University students who had gathered outside to keep up with the progress of the game.

Equipment at 5XB – Texas A&M

The equipment was constructed for the most part in the Electrical Engineering laboratory by the radio amateur students interested in the station and with the help and guidance of the head of the Electrical Engineering Department, Dean F. C. Bolton who later became President of the College. The main power transformer had been constructed for oil testing purposes and was capable of providing the power limit of two kilowatts allowable under the special experimental license of 5XB.

The transmitting condenser consisted of about 100 clear glass photographic plates interlaced with tinfoil from damaged paper condensers from the laboratory. The entire "sandwich" of glass plates and tinfoil was immersed in an oil-filled copper-lined box. Its performance was unusually good considering the voltage involved.

The oscillation transformer was "loaned" by the Signal Corps Radio Laboratory which had been established on the campus during World War I for training of military personnel. It was a real beauty consisting of heavy aluminum wire wound on separators made from genuine mahogany.

A number of rotary spark gaps were tried from time to time and the one used on the date of the broadcast was a modified commercial unit bought by Saunders on New York City's Radio Row district in the summer of 1921 while he was attending an R.O.T.C. summer training camp at Red Bank, New Jersey. The modification consisted of mounting the motor behind the control panel with its rotating shaft extended through the panel. The electrodes, both fixed and rotary, were then re-mounted on the front of the panel. A circular wooden cover with a glass front enclosed the gap forming an almost airtight unit. After a few characters were transmitted, the...oxygen would be exhausted and the note of the signal neared that of a quenched gap. Near the end of each transmission, the operator would remove the power from the motor and its flywheel effect as the speed decreased provided a unique and distinctive signature.

The antenna was suspended from a steel tower on the Electrical Engineering Building in which the station was located on the third floor to another tower atop the dormitory next door. The main station receiver was an early model Coast Guard tuner consisting of multi-tapped coils with both coarse and fine tuning taps supplemented by a variable air condenser. This tuning unit was connected to a World War I Signal Corps VT-1 vacuum tube detector unit and a two-tube audio amplifier. Filament voltage was obtained from Signal Corps alkaline storage batteries and the high voltage was provided by conventional "B" batteries. By today's standards such a receiver would be useless with crowded signals, but at that time it worked out fairly well.

WTAW

WTAW received its broadcast license on October 7, 1922.[2] Before 1923, radio stations in Texas were given call signs beginning with a W, so WTAW is one of a handful still around to this day, while most Texas stations now have call letters starting with a K.

WTAW was started as an experimental station by the Texas Agricultural College (now Texas A&M University). It was one of the first radio stations to air a live football game in real time. For the history of its experimental days, see below. For much of its early decades, WTAW was a non-commercial station owned by the college. It spent some of its early years broadcasting on AM 1120, powered at 500 watts and sharing time with other stations.[3] In the 1940s, it switched to AM 1150. It no longer had to share time with other stations but it was still limited as a 1,000 watt daytimer, required to be off the air at night.

In 1957, WTAW became a commercial station, owned by a company calling itself WTAW Broadcasting.[4] In 1962, it added an FM station, WTAW-FM, which allowed WTAW's country music format to be heard around the clock; by the 1970s, WTAW-FM had switched to an automated Top 40 format, while the AM station continued with its country sound.

In 1973 Bill Watkins, station manager and owner, hired Sunny Nash to anchor drive-time morning news. The country station's first African American reporter and talk-show host, Nash was a Texas A&M University student, who became the first African American journalism graduate in the school's history in 1977, and later a syndicated newspaper columnist and author of Bigmama Didn't Shop At Woolworth's.

In the 1980s, WTAW was authorized by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to broadcast at night, with 500 watts, while daytime power remained at 1,000 watts.[5] As country music listening shifted to FM, WTAW began adding talk shows at night. Eventually the station converted to a full-time talk outlet in the 1990s.

KZNE

In the 1990s, the FCC expanded the AM band from 1600 kHz to 1700 kHz. A new AM station for College Station was assigned at AM 1620. The current license at 1620 AM was first given the call letters KAZW on January 9, 1998. On March 1, 2000, the station's call sign changed to KZNE.[6] On May 3, 2000, WTAW and KZNE flipped call letters, with WTAW's talk format and call sign moving to AM 1620, while KZNE signed on AM 1150 with an all-sports radio format. Due to the way the transaction was structured legally, KZNE operates under WTAW's original license, while the current WTAW facility is a new license. The move allowed WTAW to boost its daytime power to 10,000 watts and increase nighttime power to 1,000 watts. However, KZNE took over WTAW's longtime role as the flagship of Texas A&M Aggies athletics; indeed, WTAW's call letters stand for "Watch The Aggies Win."

On December 4, 2003, WTAW and KZNE were sold to Bryan Broadcasting.[7]

On May 4, 2015, KZNE began simulcasting on FM translator K274CM (102.7 FM) College Station.[8] As of May 2019, the current translator is K229DK (93.7 FM).

Programming

Local programs on KZNE include TexAgs Radio, The Louie Belina Show, and Chip Howard Sports Talk. The station is also an affiliate for CBS Sports Radio and Paul Finebaum., and the flagship station for Texas A&M University athletic events.[9]

References

- "Bryan Broadcasting Corporation". Retrieved 2011-01-04.

- Broadcasting Yearbook 1950 page 288

- Broadcasting Yearbook 1935 page 58

- Broadcasting Yearbook 1960 page A-232

- Broadcasting Yearbook 1990 page B-298

- "WTAW Call Sign History". United States Federal Communications Commission, audio division. Retrieved 2009-09-10.

- "FCC Application". Federal Communications Commission. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - FM Sports Battle Rages in College Station

- "KZNE Schedule". Retrieved 2011-01-04.

External links

- Official website

- Query the FCC's AM station database for KZNE

- Radio-Locator Information on KZNE

- Query Nielsen Audio's AM station database for KZNE

- FM Translator