Jules-Albert de Dion

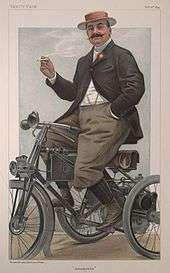

Marquis Jules Félix Philippe Albert de Dion de Wandonne (9 March 1856 – 19 August 1946) was a pioneer of the automobile industry in France.

.svg.png)

Jules-Albert de Dion | |

|---|---|

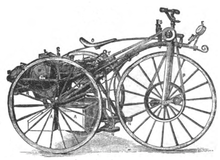

de Dion on a steam car | |

| Born | Jules Félix Philippe Albert de Dion de Wandonne 9 March 1856 Carquefou, Loire-Atlantique, France |

| Died | 19 August 1946 (aged 90) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | Automobile, motorcycle pioneer Dreyfus affair |

His life

Jules-Albert was the heir of a leading French noble family, in 1901 succeeding his father Louis Albert William Joseph de Dion de Wandonne as Count and later Marquis. A "notorious duellist", he also had a passion for mechanics.[1] He had already built a model steam engine when, in 1881, he saw one in a store window and asked about building another.[1] The engineers, Georges Bouton and his brother-in-law, Charles Trépardoux,[2] had a shop in Léon where they made scientific toys.[1] Needing money for Trépardoux's long-time dream of a steam car, they acceded to De Dion's request.[3]

During 1883 they formed a partnership which became the De Dion-Bouton automobile company, the world's largest automobile manufacturer for a time. They tried marine steam engines, but progressed to a steam car which used belts to drive the front wheels whilst steering with the rear. This was destroyed by fire during trials. In 1884 they built another, "La Marquise", with steerable front wheels and drive to the rear wheels. As of 2011, it is the world's oldest running car, and is capable of carrying four people at up to 38 mph.[2]

Comte de Dion entered one in an 1887 trial, "Europe's first motoring competition",[2] the brainchild of M. Paul Faussier of cycling magazine Le Vélocipède Illustré.[2] Evidently, the promotion was insufficient, for the de Dion was the sole entrant,[2] but it completed the course.

The de Dion tube (or 'dead axle') was actually invented by steam advocate Trépardoux, just before he resigned because the company was turning to internal combustion.[4]

In 1898 he co-founded the Mondial de l'Automobile (Paris Motor Show).

He died in 1946, age 90,[5] and is buried in the cemetery at Montparnasse in Paris. There is a memorial plaque in the family chapel in Wandonne, 3 km south of Audincthun in the Pas-de-Calais.

Racing career

Motor racing was started in France as a direct result of the enthusiasm with which the French public embraced the motor car.[6] Manufacturers were enthusiastic due to the possibility of using motor racing as a shop window for their cars.[6] The first motor race took place on 22 July 1894 and was organised by Le Petit Journal, a Parisian newspaper. It was run over the 122 kilometres (76 mi) distance between Paris and Rouen. The race was won by de Dion, although he was not awarded the prize for first place as his steam-powered car required a stoker and the judges deemed this outside of their objectives.[7]

Dreyfus affair

The roots of both the Tour de France cycle race and L'Auto (L'Équipe), a daily sporting newspaper, can be traced to the Dreyfus affair and de Dion's passionate opinion and actions regarding it.

Opinions were heated and there were demonstrations by both sides in the Dreyfus affair. Historian Eugen Weber described an 1899 conflagration at the Auteuil horse-race course in Paris as "an absurd political shindig" when, among other events, the President of France (Émile Loubet) was struck on the head by a walking stick wielded by de Dion.[8][9] He served 15 days in jail and was fined 100 francs,[9][10] and his behaviour was heavily criticised by Le Vélo, the largest daily sports newspaper in France, and its Dreyfusard editor, Pierre Giffard. The result was that de Dion withdrew all his advertising from the paper,[11][12] and in 1900 he led a group of wealthy 'anti-Dreyfusard' manufacturers, such as Adolphe Clément, to found L'Auto-Velo and compete directly with Le Velo. After a legally enforced change of name to L'Auto it in turn created the Tour de France race in 1903 to boost falling circulation.

L'Auto

In 1900 de Dion led a group of wealthy anti-Dreyfusards including Édouard Michelin to start a rival daily sports paper, L'Auto-Velo. De Dion and Michelin were particularly concerned with Le Vélo – which reported more than cycling – because its financial backer was one of their commercial rivals, the Darracq company. De Dion believed that Le Vélo gave Darracq too much attention and him too little. De Dion was an outspoken man who already wrote columns for Le Figaro, Le Matin and others. His wealth allowed him to indulge his whims, which also included refounding Le Nain jaune (The Yellow Gnome), a fortnightly publication which "answers no particular need."[13]

Notes

- Wise, David Burgess, "De Dion: The Aristocrat and the Toymaker", in Ward, Ian, executive editor. The World of Automobiles (London: Orbis Publishing, 1974), Volume 5, p. 510.

- Georgano, G. N. Cars: Early and Vintage, 1886-1930. (London: Grange-Universal, 1990), p. 27.

- Georgano, G. N. Cars: Early and Vintage, 1886-1930. (London: Grange-Universal, 1990), p. 24 cap.

- Wise, David Burgess, "De Dion: The Aristocrat and the Toymaker", in Ward, Ian, executive editor. The World of Automobiles (London: Orbis Publishing, 1974), Volume 5, p. 511.

- Wise, David Burgess, "De Dion: The Aristocrat and the Toymaker", in Ward, Ian, executive editor. The World of Automobiles (London: Orbis Publishing, 1974), Volume 5, p. 514.

- Rendall, Ivan (1995). The Chequered Flag. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 10. ISBN 0-297-83550-5.

- Rendall, Ivan (1995). The Chequered Flag. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 12. ISBN 0-297-83550-5.

- Stephen L. Harp (13 November 2001). Marketing Michelin: Advertising and Cultural Identity in Twentieth-Century France. JHU Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-8018-6651-7.

le velo newspaper.

- Weber, Eugen (2003), foreword to "Tour de France: 1903-2003", eds Dauncey, Hugh and Hare, Geoff, Routledge, USA, ISBN 978-0-7146-5362-4, p. xi.

- Boeuf, Jean-Luc, and Léonard, Yves (2003); La République de Tour de France, Seuil, France.

- Boeuf, Jean-Luc, and Léonard, Yves (2003), La République du Tour de France, Seuil, France, p. 23.

- Nicholson, Geoffrey (1991) Le Tour, the rise and rise of the Tour de France, Hodder and Stoughton, UK.

- Le Naine Jaune.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jules-Albert de Dion. |

- Georgano, G. N. Cars: Early and Vintage, 1886-1930. London: Grange-Universal, 1990 (reprints AB Nordbok 1985 edition).

- Wise, David Burgess, "De Dion: The Aristocrat and the Toymaker", in Ward, Ian, executive editor. The World of Automobiles (London: Orbis Publishing, 1974), Volume 5, p. 510-4.

- Profile on Historic Racing