John Seward Johnson II

John Seward Johnson II (April 16, 1930 – March 10, 2020), also known as J. Seward Johnson Jr. and Seward Johnson, was an American artist known for his trompe l'oeil painted bronze statues. He was a grandson of Robert Wood Johnson I, the co-founder of Johnson & Johnson and Colonel Thomas Melville Dill of Bermuda.

John Seward Johnson II | |

|---|---|

| Born | April 16, 1930 |

| Died | March 10, 2020 (aged 89) Key West, Florida, US |

| Occupation | Artist |

| Spouse(s) | Barbara Kline [1](m. 1956; div. 1965) Joyce Horton (m. 1965) [2] |

| Children | Jenia Anne "Cookie" Johnson John Seward Johnson III Clelia Constance Johnson |

| Parent(s) | John Seward Johnson I Ruth Dill |

| Website | www.sewardjohnson.com |

He created life-size bronze statues, castings of living people, depicting them engaged in day-to-day activities. A large staff of technicians usually did the actual fabrication of works he designed. He was the founder of Grounds For Sculpture, a 42-acre (17 ha) sculpture park and museum located in Hamilton Township, Mercer County, New Jersey.

Early life

Johnson was born in New Brunswick, New Jersey on April 16, 1930.[3] His father was John Seward Johnson I, and his mother was Ruth Dill, the sister of actress Diana Dill, making him a first cousin of actor Michael Douglas. Johnson grew up with five siblings: Mary Lea Johnson Richards, Elaine Johnson, Diana Melville Johnson, Jennifer Underwood Johnson, and James Loring "Jimmy" Johnson. His parents divorced around 1937, and his father remarried two years later, producing his only brother Jimmy Johnson, making him an uncle to film director Jamie Johnson.[4]

Johnson attended Forman School for dyslexics[5] and the University of Maine, where he majored in poultry husbandry, but did not graduate.[6] Johnson also served four years in the United States Navy during the Korean War.[5]

Career

Johnson worked for Johnson & Johnson until he was fired by his uncle Robert Wood Johnson II, in 1962.[7]

Johnson maintained a studio in Princeton, New Jersey and then another at the former New Jersey Fairgrounds in Mercerville, New Jersey.[8]

His early artistic efforts focused on painting, after which he turned to sculpture in 1968. Examples of his statues include:

- Spring (1979), a bronze dedicated in 1979,[9] set in the Crim Dell Woods section of the College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia. Other examples of Spring castings include the East Brunswick, New Jersey public library and the Fitton Center for Creative Arts in Hamilton, Ohio.[10]

- The Awakening (1980), his largest and most dramatic work, a 70-foot (21 m) five-part statue that depicts a giant trying to free himself from underground. The sculpture was located at Hains Point in Washington, DC for nearly twenty-eight years while still owned by Johnson. It was moved to Prince George's County, Maryland in February 2008, and an attempt was made by the new curator to correct some of the scale distortions of the original installation by altering some implied underground connections and placing the parts in different relationships to each other.

- Double Check (1982), a statue of a businessman checking his attaché case, formerly located in Liberty Plaza Park across an intersection from the World Trade Center, as part of the public space required by a zoning variance granted to the developer of the adjoining skyscraper. Widely published photographs of the debris-battered and dust-covered statue, were taken following the September 11 terrorist attacks in 2001. The statue, scars and all, was returned to a prominent corner of the restored and renamed Zuccotti Park in 2006, again open to the public. The statue has periodically been adorned by tourists, pranksters and even Occupy Wall Street protesters.

- Hitchhiker (1983), a statue at Hofstra University, at the California Avenue gate, near a road leading away from campus.[11]

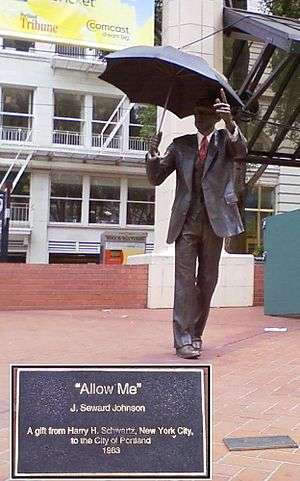

- Allow Me (Portland, Oregon) (1984), a statue of man holding an umbrella, in Pioneer Courthouse Square in Portland, Oregon (part of the Allow Me series).

- Competition (1984), A sculpture of Julie Wier, Fairview Heights, Illinois. Chosen to represent the spirit of the people of St. Louis as winner of the "picture yourself as a work of art" contest. Dedicated on June 16, 1984 unsigned St. Louis County Library in St. Louis, Missouri.

- Waiting (1988), at Australia Square, Sydney, Australia

- Déjeuner Déjà Vu (1994), at Grounds for Sculpture in Hamilton Township, Mercer County, New Jersey, a facility founded by Johnson, is a three-dimensional restaging of Édouard Manet's painting, Le déjeuner sur l'herbe[12]

- Copyright Infringement (1994), at Grounds for Sculpture (a facility founded by Johnson) is a sculpture that he named to flaunt his disdain for criticism of his copies of the iconic works of fine art artists with international recognition, and represents the fine artist Edouard Manet, whose work he has copied.

- Unconditional Surrender (a series with several versions begun in 2005), a spokesperson for Johnson has stated that this series is based on a photograph that is in the public domain, Kissing the War Goodbye, by Victor Jorgensen,[13] however, the Jorgensen photographic image does not extend low enough to include the lower legs and shoes of the subjects, revealed in Alfred Eisenstaedt's famous photograph, V–J day in Times Square, that are represented identically in the statue. A spokesperson for Life has called it a copyright infringement of the latter image.[13] Nonetheless, the first version, a bronze statue in life-size, was placed on temporary exhibition during the 2005 anniversary of V-J Day at the Times Square Information Center near where the original photographs were taken in Manhattan.[14]

- Several slightly differing twenty-five-foot-versions have been constructed in styrofoam and aluminum with little detail, painted, and put on display by Johnson in San Diego, California,[13][15] Key West, Florida, Snug Harbor in New York, and Sarasota, Florida. Their immensity has drawn crowds of viewers at each site although the view of them from nearby is severely limited, essentially allowing a vista of the legs and up the skirt. The statues have been described as kitsch by one critic.[13]

- A proposal to establish a permanent location for a copy on the Sarasota bay front has generated a heated controversy about the suitability of the statue to the location, suitability as a military service memorial,[16] the permanent placement of any statue on that public property, as well as the particular issues of unoriginality, mechanical construction, and alleged kitschiness of the statue.[17][18] In final agreement documents, Johnson committed the purchase price to cover copyright liability damages in order to have the statue placed. The city was wary of accepting a gift that might result in a financial loss from a possible legal battle that evidenced merit, according to the city attorney.[19]

- In October 2014, French feminist group Osez La Feminisme ! petitioned to have a copy of the statue, erected at a World War II memorial in Normandy in September 2014,[20] removed and sent back to the United States, criticizing it as "immortali[zing] a sexual assault"[21]

- Big Sister, just outside the Pig 'N' Whistle pub and Michael's Restaurant at 123 Eagle Street, part of the Celebrating the Familiar series

- First Ride (2006), a statue of a father helping his young daughter learn to ride a bike, in Carmel, Indiana.[22]

- Newspaper Reader, at the entrance to Steinman Park, Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

- Forever Marilyn (June 2011), a 26-foot (7.9 m), 17-ton representation of Marilyn Monroe standing over a gusty subway grate in her appearance in The Seven Year Itch. Until 2012, the sculpture was located at Pioneer Court in Chicago, where it attracted many visitors and some controversy. It was moved to downtown Palm Springs, California in 2012 and in July 2013 P.S. Resorts announced that The Sculpture Foundation, owners of Forever Marilyn, would be moving it to New Jersey for a 2014 exhibit honoring Johnson at the Grounds For Sculpture.[23]

For statues made in a series named, Iconic, by Johnson,[24] many of which are very large, a computer program is employed that translates two-dimensional images into statues that are constructed by a machine driven by the program. Often, these subjects are images that already are well known as the works of others, generating heated ethical controversies regarding copyright infringement and derivative works due to substantial similarity issues.

Johnson's works were selected by the United States Information Agency to represent the freedoms of the United States in a public and private partnership enterprise representation sponsored by General Motors and many other US corporations at the World EXPO celebration in Seville, Spain during 1992.[24]

Criticism

Johnson's work was labeled as "kitsch" in a 1984 article by an art professor and critic at Princeton University, who explained its rejection as he was commenting on a controversy raging about the work in New Haven, Connecticut.[25]

His 2003 show at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Beyond the Frame: Impressionism Revisited, which presented his statues imitating famous Impressionist paintings, was a success with audiences, but was panned nationally acknowledged art critics such as Blake Gopnik writing for the Washington Post and drew strong criticism from curators at other museums about a prominent museum of fine art presenting an exhibit of his work.[26][27]

Philanthropy

Johnson was the chairman and CEO of The Atlantic Foundation, the foundation created by his father John Seward Johnson I in 1963. Johnson created the Johnson Atelier Technical Institute of Sculpture, an educational, nonprofit casting and fabrication facility in 1974 as a means of fostering young sculptors' talents, while creating a foundry designed to construct his statues that is so well-equipped and staffed that it is chosen by many renowned sculptors.[24] Educational programs at the Atelier ceased in 2004. The Johnson Atelier now operates as a division of The Sculpture Foundation, and Johnson continued to make his sculpture at the facility but casting is often performed off premises, with some of his larger works being cast in the Peoples Republic of China.

He also founded an organization named "The Sculpture Foundation", to promote his works. In 1987, he published Celebrating the Familiar: The Sculpture of J. Seward Johnson, Jr.[24]

Under Johnson's direction, The Atlantic Foundation purchased the old New Jersey Fairgrounds in Hamilton, New Jersey and in 1992 founded the Grounds For Sculpture to display work completed at the Johnson Atelier and other outdoor exhibitions. In 2000 park operations were transferred to a new public charity with the same intent that continues to operate the park.[24]

He was president of the International Sculpture Center of Hamilton, New Jersey, which publishes a magazine out of offices in Washington, DC.[24]

Johnson also was the president of a large oceanographic research institution in Florida founded by his father, the publisher of a science magazine, Johnson and his wife funded the construction of The Joyce and Seward Johnson Theater for the Theater for the New City, an Off-Broadway theater in New York City.[24]

Personal life

Johnson was excluded from his father's will, which left the bulk of his fortune to Barbara Piasecka Johnson, his father's wife and former chambermaid. He and his siblings sued on grounds that their father wasn't mentally competent at the time he signed the will. It was settled out of court, and the children were granted about 12% of the fortune.[28]

Johnson was formerly married to Barbara Kline. She often engaged in extramarital affairs in their home, driving Johnson to attempt suicide.[4][29][30] In 1965, he acknowledged paternity to Jenia Anne "Cookie" Johnson to speed up the divorce process.[31][32] Years later, Johnson's family had a legal battle regarding Cookie Johnson's eligibility for a share in the Johnson & Johnson fortune. The court ruled in favor of Cookie.[33]

Johnson later married Joyce Horton, a novelist. They had two children, John Seward Johnson III and actress Clelia Constance Johnson, who is credited as "India Blake."[5]

Johnson died from cancer at his home in Key West, Florida on March 10, 2020.[3] He was 89.

See also

References

- "Crazy Rich: Power, Scandal, and Tragedy Inside the Johnson & Johnson Dynasty - Jerry Oppenheimer - Google Books". Books.google.ca. 2013-08-13. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- "JOHNSON V. JOHNSON - Barbara Goldsmith - Google Books". Books.google.ca. 2011-08-24. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- Genzlinger, Neil (March 12, 2020). "J. Seward Johnson Jr., Sculptor of the Hyper-Real, Dies at 89". The New York Times. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- McMurran, Kristin. "The Band-Aid Heir Left All He Owned to His Widow, but His Children Claim It Was Just Seward's Folly". People.com. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- Reed, J. D. (June 30, 2002). "Seward's Follies". The New York Times. Retrieved May 7, 2010.

- "Chris Farrell Membership - "Online Success - Made Simple..."". Nantucketindependent.com. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- "A Matter of Opinion". www.daytondailynews.com. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- Seward Johnson

- "'Spring,' Dedicated 1979". Special Collections Research Center, William & Mary Libraries. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- Hogan, Claire (19 February 2019). "Stranger Places: The 'Spring' Statue". Flat Hat News. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- Nguyen, Daniel (14 November 2017). "Hofstra's most overlooked art is right outside". Hofstra Chronicle. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- Page on Johnson's site

- Robert L. Pincus, "Port surrenders in the battle against kitsch Archived 2011-07-17 at the Wayback Machine", San Diego Union-Tribune, March 11, 2007.

- "V-J Day Is Replayed, but the Lip-Lock's Tamer This Time", New York Times, August 15, 2005.

- midnight (2009-11-08). "comparison with other statues placed at San Diego". Signonsandiego.com. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- "criticism by veteran and former Life magazine editor, Sarasota Herald Tribune, August 22, 2009". Heraldtribune.com. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- "Notice: Trying to get property of non-object in /var/www/lib/inc/header.php on line 37 — Gainesville.com Videos Notice: Trying to get property of non-object in /var/www/lib/inc/header.php on line 38". Heraldtribune.com. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- "Unconditional Surrender Statue". Roadsideamerica.com. 1945-08-14. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- "Ogles, Jacob, Unconditional Surrender Deal to Be Finalized Today, SRQ Daily, June 11, 2010". Srqmagazine.com. 2010-11-06. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- PRESS, ASSOCIATED (23 September 2014). "WWII kissing statue lands in Normandy".

- "Iconic 'kiss' sculpture depicts sexual assault says French feminist group".

- "Arts and Design District Hosts New Holiday Event" (PDF). City of Carmel Newsletter. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-05-08.

- "Business News: Forever Marilyn to Stay in Palm Springs until Mid-November". The Public Record. 37 (32): 3. July 30, 2013. ISSN 0744-205X. OCLC 8101482.

- "Seward Johnson". Seward Johnson. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- Neuhaus, Cable (1984-03-26). "Cast in Bronze and Controversy, Sculptor J. Seward Johnson's Works Find No Haven in New Haven". People.com. Retrieved 2010-06-08.

- Gopnik, Blake (2012-08-21). "A Bad Impression. At the Corcoran Gallery, Seward Johnson's Travesty in Three Dimensions". Washington Post.

- Clemonson, Lynette (2005-05-28). "Corcoran, After Dispute, Casts About for New Path". Nytimes.com.

- Margolick, David (May 4, 1990). "Mary Lea Johnson Richards, 63, Founder of Production Company". The New York Times.

- Lovenheim, Barbara (June 21, 1987). "Family Fortune: Tangled Tale". The New York Times. Retrieved May 7, 2010.

- New York Magazine. 1987-02-23. p. 129. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- Jackson, Herb. "NJCA in the News". Njcitizenaction.org. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- Editors, Silver Lake (April 2001). Page 14. ISBN 9781563437441. Retrieved 2013-04-09.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Editors, Silver Lake (April 2001). Pages 14–17. ISBN 9781563437441. Retrieved 2013-04-09.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

Further reading

- Goldsmith, Barbara (1988). Johnson v. Johnson. New York, NY: Dell. ISBN 0-440-20041-5.

- Levy, David C. (foreword); Chu, Petra ten-Doesschate (essay); Grooms, Red (conversation) (2003). Beyond the frame : Impressionism revisited : the sculptures of J. Seward Johnson, Jr : Exhibition catalog. Boston: Bulfinch Press. ISBN 0-8212-2878-1.

- Margolick, David (1993). Undue influence : the epic battle for the Johnson & Johnson fortune (1 ed.). New York: Morrow. ISBN 0-688-06425-6.

- Johnson, J. Seward Jr. (1987). Celebrating the familiar : the sculpture of J. Seward Johnson, Jr (1st ed.). New York: Van Der Marck. ISBN 0-912383-57-7.

External links

![]()