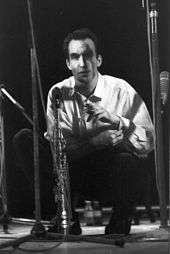

John Lurie

John Lurie (born December 14, 1952) is an American musician, painter, actor, director, and producer. He co-founded The Lounge Lizards jazz ensemble, acted in 19 films, including Stranger than Paradise and Down by Law, composed and performed music for 20 television and film works, and produced, directed, and starred in the Fishing with John television series. In 1996 his soundtrack for Get Shorty was nominated for a Grammy Award, and his album The Legendary Marvin Pontiac: Greatest Hits has been praised by both critics and fellow musicians.

John Lurie | |

|---|---|

Lurie in 2013 | |

| Born | December 14, 1952 Minneapolis, Minnesota, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1978–present |

| Television | Fishing with John, Oz |

| Website | www |

Since 2000, Lurie has suffered from symptoms attributed to "chronic Lyme disease" and has focused his attention on painting.[1] His art has been shown in galleries and museums around the world. His primitivist painting Bear Surprise became an internet meme in Russia in 2006.

Early life

Lurie was born in Minneapolis and was raised with his brother Evan and his sister Liz in New Orleans, Louisiana and Worcester, Massachusetts.[2] [3]

In high school, Lurie played basketball and harmonica and jammed with Mississippi Fred McDowell and Canned Heat in 1968.[2] He briefly played the harmonica in a band from Boston but soon switched to the guitar and eventually the saxophone.[4]

After high school, Lurie hitchhiked across the United States to Berkeley, California. He moved to New York City in 1974, then briefly visited London where he performed his first saxophone solo at the Acme Gallery.[2]

Music

The Lounge Lizards

In 1978 John formed The Lounge Lizards with his brother Evan Lurie; they were the only constant members in the band through numerous lineup changes.

Robert Palmer of The New York Times described the band as "staking out new territory west of Mingus, east of Bernard Herrman." While originally a somewhat satirical "fake jazz" combo spawned by the noisy No Wave music scene, the Lounge Lizards gradually became a showcase for Lurie's increasingly sophisticated compositions. The band's personnel included guitarists Arto Lindsay, Oren Bloedow, David Tronzo, and Marc Ribot; drummers Grant Calvin Weston, Dougie Bowne, and Billy Martin; bassists Erik Sanko and Tony Garnier; trumpeter Steven Bernstein; and saxophonists Roy Nathanson and Michael Blake. The band made music for 20 years.

Marvin Pontiac

In 1999 Lurie released the album The Legendary Marvin Pontiac: Greatest Hits, a posthumous collection of the work of an African-Jewish musician named Marvin Pontiac, a fictional character Lurie created. It includes a biographical profile describing the troubled genius's hard life, and the cover shows a photograph purported to be one of the few ever taken of him.[5] Lurie wrote the music and performed with John Medeski, Billy Martin, G. Calvin Weston, Marc Ribot, and Tony Scherr. The album received praise from David Bowie, Angelique Kidjo, Iggy Pop, Leonard Cohen and others.

"For a long time, I was threatening to do a vocal record. But the idea of me putting out a record where I sang seemed ostentatious or pretentious. Like the music of Telly Savalas . . . I don't sing very well, I was shy about it. As a character, it made it easier."[5]

In 2017, after 17 years, John Lurie released his first music album, Marvin Pontiac The Asylum Tapes.[6]

John Lurie National Orchestra

Parallel to the final version of the Lounge Lizards in the early 1990s, Lurie formed a smaller group, the John Lurie National Orchestra, with Lurie on alto and soprano saxes, Grant Calvin Weston on drums, and Billy Martin on congas, timbales, kalimba, and other small percussion. Unlike the tightly-arranged music of the Lounge Lizards, the Orchestra's music was heavily improvised and compositions were credited to all three musicians.

They released an album (Men With Sticks, Crammed Discs 1993) and recorded music for the Fishing With John TV series. In February 2014 the Orchestra released The Invention of Animals, a collection of out-of-print studio tracks and unreleased live recordings from the '90s. Columnist Mel Minter wrote:

This new release may require a reassessment of Lurie the saxophonist because the playing is engagingly fluid, inventive, and visceral—and well worth revisiting. . . . The emotional immediacy of Lurie's playing – and that of his partners – makes for riveting stuff. Think of his sax not so much as a musical instrument, but instead, as a window with a clear view of his soul.[7][8]

Jeff Jackson of Jazziz added, "The resulting music is delicate, primal and utterly gorgeous."[9]

Film and television

In 1993 Lurie composed the theme to Late Night with Conan O'Brien with Howard Shore. The theme was also used when O'Brien hosted on The Tonight Show. Lurie formed his own record label in 1998, Strange & Beautiful Music, and released the Lounge Lizards album Queen of All Ears and a Fishing with John soundtrack.

Lurie has written scores for over 20 movies, including Stranger than Paradise, Down by Law, Mystery Train, Clay Pigeons, Animal Factory, and Get Shorty, for which he received a Grammy Award nomination.[10]

In the 1980s, Lurie starred in the Jim Jarmusch films Stranger Than Paradise and Down by Law, and made cameos in the films Permanent Vacation and Downtown 81. He went on to act in other notable films including Paris, Texas and The Last Temptation of Christ. From 2001 to 2003 he starred in the HBO prison series Oz as inmate Greg Penders.[11]

Lurie wrote, directed and starred in the TV series Fishing with John in 1991 and 1992, which featured guests Tom Waits, Willem Dafoe, Matt Dillon, Jim Jarmusch, and Dennis Hopper. It aired on IFC and Bravo. It has since become a cult classic[12] and was released on DVD by Criterion.

Painting

.jpg)

Lurie has been painting since the 1970s.[13] Most of his early works are in watercolor and pencil, but in the 2000s he began working in oil. He has said of his art, "My paintings are a logical development from the ones that were taped to the refrigerator 50 years ago."[14]

His work has been exhibited since July 2003, when two pieces were shown at the Nolan/Eckman Gallery in New York City.[15] He had his first solo gallery exhibition at Anton Kern Gallery in May and June 2004 and has subsequently been exhibited at Galerie Daniel Blau in Munich, Galerie Lelong in Zürich, the Galerie Gabriel Rolt in Amsterdam, the Basel International Art Fair at Roebling Hall and the P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center in New York, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, the NEXT Art Fair in Chicago, the Mudam Luxembourg, the Watari Museum of Contemporary Art in Tokyo, Gallery Brown in Los Angeles, and the University of the Arts in Philadelphia.[16][13][15]The Museum of Modern Art has acquired some of his work for their permanent collection.[17]

Lurie has released two art books. Learn To Draw, a compilation of black and white drawings, was published by Walther Konig in June 2006. A Fine Example of Art includes over 80 reproductions of his work and was published by powerHouse Books in 2008.

Lurie's watercolor painting Bear Surprise was enormously popular on numerous Russian websites in an Internet meme known as Preved.[18]

Personal life

Lurie has experienced debilitating ill health since 2000, with initially baffling neurological symptoms.[10] At one point he was told he had a year to live.[4] The doctors he consulted in the first few years did not agree on a diagnosis, but by 2006 eight separate doctors agreed that it was chronic Lyme disease.[19] Lurie has stated, "I have Advanced Lyme."[2] He initially became ill in 1994.[10] The illness prevents him from acting or performing music, so he spends his time painting.[2][20]

Stalking incident

In August 2010, Tad Friend wrote a piece in The New Yorker about Lurie disappearing from New York to avoid a man named John Perry, who Friend said was stalking Lurie.[21] In the online literary magazine The Rumpus, Rick Moody noted that Friend's profile in The New Yorker, nominally about Lurie and his art, was two-thirds to three-quarters about Perry, including a full page photo of Perry standing in front of one of his own paintings. Moody confirmed that Lurie was very ill with "chronic Lyme disease" and described Perry as a deceitful stalker capable of violence.[19]

In May 2011 Perry undertook a public hunger strike to protest The New Yorker characterizing him as a stalker. Commenting about the protest, Lurie said, "He's conducting a hunger strike a half block from my house to prove he's not a stalker."[22] Lurie described the article as "wildly inaccurate," noting that its publication did not resolve anything and that "the situation continues."[10]

Editor David Remnick said the piece in his magazine was "thoroughly reported and fact-checked".[22] But in a letter to The New Yorker in August 2012, several interviewees claimed their words had been "twisted, misquoted, or ignored," and that "the man presented in the article [Lurie] is not the man that we know."[23] In a February 2014 interview, Lurie told the Los Angeles Times, "What one would hope is that the beauty in the music and in the paintings can somehow transcend and invalidate the kind of sickness that led to the article being written as it was and the kind of irresponsibility that allowed it to be published."[24]

Filmography

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1978 | Rome '78 | Unknown | |

| 1979 | Men in Orbit | Astronaut | Also writer, director |

| 1980 | Underground U.S.A. | Jack Smith | |

| The Offenders | The Lizard | ||

| Permanent Vacation | Sax player | Also composer | |

| 1981 | Downtown 81 | Himself | |

| Subway Riders | The Saxophonist | Also composer | |

| 1983 | Variety | N/A | Composer |

| 1984 | Stranger Than Paradise | Willie | Also composer |

| Paris, Texas | Slater | ||

| 1985 | Desperately Seeking Susan | Neighbor Saxophonist | |

| 1986 | Down by Law | Jack | Also composer |

| 1988 | The Last Temptation of Christ | James | |

| Il piccolo diavolo | Cusatelli | English title: The Little Devil | |

| 1989 | Mystery Train | N/A | Composer |

| 1990 | Wild at Heart | Sparky | |

| 1991 | Fishing with John | Himself | Also creator, director, composer |

| Keep It for Yourself | N/A | Short film; composer | |

| 1992 | John Lurie and the Lounge Lizards Live in Berlin 1991 | Himself | Documentary |

| 1993 | Late Night with Conan O'Brien | N/A | Composed title theme |

| 1995 | Get Shorty | N/A | Composer |

| Blue in the Face | N/A | Composer | |

| 1996 | Just Your Luck | Coker | |

| Manny & Lo | N/A | Composer | |

| 1997 | Excess Baggage | N/A | Composer |

| 1998 | New Rose Hotel | Distinguished Man | |

| Lulu on the Bridge | N/A | Composer | |

| Clay Pigeons | N/A | Composer | |

| 2000 | Sleepwalk | Frank | |

| Animal Factory | N/A | Composer | |

| 2001 | SpongeBob SquarePants | Himself | Archival footage from Fishing With John (Episode: "Hooky") |

| 2001–03 | Oz | Greg Penders | 12 episodes |

| 2004 | Tortured by Joy | Narrator | Short film |

| 2005 | Face Addict | N/A | Composer |

| 2010–11 | Mobsters | Narrator | |

Discography

John Lurie

- John Lurie National Orchestra, The Invention of Animals, 2014[25]

- John Lurie National Orchestra: Men with Sticks (Crammed Discs/Made to Measure, 1993)

- The Legendary Marvin Pontiac: Greatest Hits (Strange and Beautiful Music, 1999)

- Marvin Pontiac: The Asylum Tapes (Strange and Beautiful Music, 2017)[26]

Lounge Lizards

- Lounge Lizards (Editions EG/Polydor, 1981)

- Live from the Drunken Boat (Europe, 1983)

- Live: 1979–1981 (ROIR, 1985)

- Big Heart: Live in Tokyo (Island, 1986)

- No Pain for Cakes (Island, 1986)

- Voice of Chunk (VeraBra, 1988)

- Live in Berlin, Volume One (VeraBra, 1992)

- Live in Berlin, Volume Two (VeraBra, 1993)

- Queen of All Ears (Strange and Beautiful Music, 1998)

Soundtracks

- Stranger Than Paradise and The Resurrection of Albert Ayler (Crammed Discs/Made to Measure, 1986)

- Down by Law and Variety (Crammed Discs/Made to Measure, 1987)

- Mystery Train (Milan/RCA, 1989)

- The Days with Jacques (Sony Records, 1994)

- Get Shorty (Verve, 1995)

- Excess Baggage (Prophecy, 1997)

- Fishing with John (recorded in 1991; Strange and Beautiful Music, 1998)

- African Swim and Manny & Lo (Strange and Beautiful Music, 1999)

References

- "John Lurie Art". Retrieved January 23, 2013.

- Brown, Tim (December 2006). "John Lurie". Perfect Sound Forever. Retrieved January 24, 2013.

- Forson, Kofi (April 2011). "APRIL 2011: JOHN LURIE DISCUSSION PART 2". Whitehot Magazine. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- Ortiz, Alan (March 1, 2009). "Q&A: JOHN LURIE (Unabridged)". Stop Smiling. Retrieved January 24, 2013.

- Robins, Wayne. "Behind The Legend of the Legendary Marvin Pontiac: A Conversation with John Lurie". eMusic. Retrieved February 2, 2013.

- http://geni.us/TheAsylumTapes

- Minter, Mel. "Three Saxophones: Two Reviews and One Preview". Musically Speaking. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- Sweetman, Simon. "The John Lurie National Orchestra: The Invention of Animals". Off The Tracks. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- Jackson, Jeff (Spring 2014). "The John Lurie National Orchestra "The Invention of Animals"". Jazziz: 117.

- Sutton, Larson (February 1, 2011). "John Lurie Sustains". jambands.com. Retrieved January 24, 2013.

- "John Lurie". IMDb. Retrieved January 24, 2013.

- Fishing with John on BBC, accessed February 15, 2011

- "John Lurie: The Erotic Poetry of Hoog". Archived from the original on March 7, 2012. Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- "Melancholy Mirth". The Inquirer Digital: Arts & Entertainment. Retrieved March 4, 2011.

- "Strange & Beautiful". Retrieved February 14, 2011.

- "John Lurie: Works on Paper". MOMA PS1. May 2006. Retrieved August 19, 2013.

- "MoMA collection". Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- "The "preved" phenomenon gained enormous popularity on the Russian-language Internet with the speed of an avalanche". The Moscow Times. Retrieved January 25, 2013.

- Moody, Rick (June 24, 2011). "SWINGING MODERN SOUNDS #30: What Is and Is Not Masculine". The Rumpus. Retrieved January 24, 2013.

- Forson, Kofi (September 2009). "In Conversation with John Lurie". Whitehot Magazine. Retrieved January 24, 2013.

- Friend, Tad (August 16, 2010). "Sleeping With Weapons". The New Yorker. Retrieved January 24, 2013.

- Palmeri, Tara (June 24, 2011). "The squawk of the town". NY Post. Retrieved January 24, 2013.

- "John Lurie profile in The New Yorker". Retrieved January 24, 2013.

- Barton, Chris (February 4, 2014). "John Lurie re-emerges with 'Invention of Animals'". LA Times. Retrieved March 31, 2014.

- Masters, Mark (January 20, 2014). "The John Lurie National Orchestra: The Invention of Animals Album Review". Pitchfork. Retrieved January 23, 2017.

- Petrusich, Amanda (November 28, 2017). "Out of Nowhere, New Music from John Lurie's Made-Up Outsider Artist". The New Yorker. Retrieved December 10, 2017.

External links

- John Lurie on IMDb