Jiaozhi

Jiaozhi (Chinese: 交趾, 交阯; pinyin: Jiāozhǐ; Wade–Giles: Chiāo-chǐh; Vietnamese: Giao Chỉ), was the Chinese name for various provinces, commanderies, prefectures, and counties in northern Vietnam from the era of the Hùng kings to the middle of the Third Chinese domination of Vietnam (c. 7th–10th centuries) and again during the Fourth Chinese domination (1407–1427).

| History of Vietnam (Names of Vietnam) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Name

According to James Chamberlain, 'Jiao' originated as a cognate of Lao.[1] According to Michel Ferlus, the Sino-Vietnamese 'Jiao' in Jiaozhi (jiāo zhǐ 交趾), together with the ethnonym and autonym of the Lao people (lǎo 獠), and the ethnonym Gelao (Gēlǎo 仡佬), a Kra population scattered from Guizhou (China) to North Vietnam, would have emerged from the Austro-Asiatic *k(ə)ra:w 'human being'.[2][3] The etymon *k(ə)ra:w would have also yielded the ethnonym Keo/ Kæw kɛːwA1, a name given to the Vietnamese by Tai speaking peoples, currently slightly derogatory.[4] In Pupeo (Kra branch), kew is used to name the Tay (Central Tai) of North Vietnam.[5]

Some scholars like Joachim Schliesinger and James Chamberlain claim that the Vietnamese language was not originally based in the area of the Red River in what is now northern Vietnam. According to them, the Red River Delta region was originally Tai-speaking, ethnic Li people in particular. They claim that the area become Vietnamese-speaking only between the seventh and ninth centuries AD,[6] or even as late as the tenth century, as a result of immigration from the south, i.e., modern central Vietnam.[7][8][1] According to ancient records, Jiaozhi in the Han and Tang eras was heavily populated by Ethnic Li people.[9][10][11]

On the other hand, Ferlus (2009) showed that the inventions of new terms for pestle, oar and a pan to cook sticky rice took place in Northern Vietic (Việt–Mường) and Central Vietic (Cuoi-Toum).[12] The new vocabularies of these inventions were proven to be derivatives from original verbs rather than borrowed lexical items. The current distribution of Northern Vietic also correspond to the area of Dong Son culture. Thus, Ferlus conclude that the Northern Vietic (Viet-Muong) is the direct heirs of the Dongsonian, who have resided in Southern part of Red river delta and North Central Vietnam since the 1st millennium BC.[12]

Furthermore, John Phan (2013, 2016)[13][14] argues that “Annamese Middle Chinese” and northern Vietic was spoken in the Red River Valley and Annamese was later absorbed into the coexisting Proto-Viet-Muong, one of whose divergent dialect evolved into Vietnamese language.[15]

The name of the territory was also used to refer to the Lac people and their ancient language. It seems to be a Yue or Viet endonym of uncertain meaning, although it has had various folk etymologies over the years. In his Tongdian, Du You wrote that "The Jiaozhi are the southern people: the big toe points to the outside of the foot, so if the man stands up straight, the two big toes point to each other, so people call them the "jiaozhi"." (The Chinese character 趾 means "hallux, big toe".) The Ciyuan disputed this:

The meaning of the word Jiaozhi cannot be understood literally, but the ancient Greek method of "opposite pillar" and "connecting pillar" to label humans on earth—where "opposite pillar" stood for the South side and its logical opposite the North side, whilst "connecting pillar" stood for the East side with the West side connected to it—could provide a suggested origin. If Jiaozhi was intended to characterize "opposite pillar" because this was what people of the North called the people of the South, then the feet of the North side (chân phía Bắc') and feet of the South side (chân phía Nam) must oppose each other, therefore rendering it impossible for the feet of a person to cross or intersect each other (không phải thực là chân người "giao" nhau).[16]

Various Vietnamese scholars such as Nguyễn Văn Siêu and Đặng Xuân Bảng have since echoed this explanation.

Jiaozhi, pronounced Kuchi in the Malay, became the Cochin-China of the Portuguese traders c. 1516, who so named it to distinguish it from the city and the Kingdom of Cochin in India, their first headquarters in the Malabar Coast. It was subsequently called "Cochinchina".[17][18] However by viewpoint of researcher Trần Như Vĩnh Lạc, 交趾 or 交阯 in the transcribing a pronunciation "Viet" (越), as "/ˈɡw:ət/" in the ancient Annamese.

History

Van Lang

The native state of Văn Lang is not well attested, but much later sources name Giao Chỉ as one of the realm's districts (bộ). Its territory purportedly comprised present-day Hanoi and the land on the right bank of the Red River. The Van Lang fell to the Âu under prince Thục Phán around 258 BC. By researcher Lê Văn Lan, "文郎" was the Chinese script of the "urang" or "orang" in the Proto-Malayo-Polynesian.

Âu Lạc

Thục Phán established his capital at Co Loa in Hanoi's Dong Anh district. The citadel was taken around 208 BC by the Qin general Zhao Tuo. By Lê Văn Lan.

Nanyue

Zhao Tuo declared his independent kingdom of Nanyue in 204 and organized his Vietnamese territory as the two commanderies of Jiaozhi and Jiuzhen (Vietnamese: Cửu Chân; present-day Thanh Hóa, Nghệ An, and Hà Tĩnh). Following a native coup that killed the Zhao king and his Chinese mother, the Han launched two invasions in 112 and 111 BC that razed the Nanyue capital at Panyu (Guangzhou).

Han dynasty

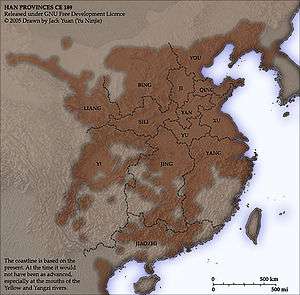

The Han received the submission from the Nanyue commanders in Jiaozhi and Jiuzhen, confirming them in their posts and ushering in the "First Northern Domination" of Vietnam. (Shu Âu Lạc and Chinese Nanyue both reckoned by the Vietnamese as "native" states.) These commanderies were headed by grand administrators (taishou) who were later overseen by the inspectors (刺史, cishi) of Jiaozhou or "Jiaozhi Province" (Giao Chỉ bộ), the first of whom was Shi Dai.

Under the Han, the capital of Jiaozhi was first Mê Linh (Miling) (within Hanoi's Me Linh district) and then Luy Lâu, within Bac Ninh's Thuan Thanh district.[19] According to the Book of Han’s "Treatise on Geography", Jiaozhi contained 10 counties: Leilou (羸𨻻), Anding (安定), Goulou (苟屚), Miling (麊泠), Quyang (曲昜), Beidai (北帶), Jixu (稽徐), Xiyu (西于), Longbian (龍編), and Zhugou (朱覯). Đào Duy Anh stated that Jiaozhi's territory contained all of Tonkin, excluding the regions upstream of the Black River and Ma River.[20] Southwestern Guangxi was also a part of Jiaozhi.[20] The southwest area of present-day Ninh Bình was the border of Jiuzhen. Later, the Han dynasty created another commandery named Rinan (Nhật Nam) located south of Jiuzhen from the Ngang Pass to Quảng Nam Province.

One of the Grand Administrators of Jiaozhi was Su Ding.[21] Ma Yuan's bronze column was supposedly erected by Ma Yuan after he had suppressed the uprising of the Trưng Sisters in the early 40s. Ma Yuan followed his conquest with a brutal course of assimilation, destroying the natives' bronze drums in order to build the column at the edge of Chinese territory. Six Chinese characters were carved upon it: "If this bronze column collapses, Jiaozhi will be destroyed" (銅柱折 交趾滅). The location of the column is unknown, with various explanations given for its disappearance. One popular story is that locals developed a superstitious habit of placing rocks to support the column as they passed and that, over time, this pile grew so large that it completely covered the columns. Another is that they threw the rocks from hatred. Later rationalist Chinese and Vietnamese scholars opined that it had probably simply fallen into the sea in the course of an earthquake or change of shoreline.

During the rule of Emperor Ling (168-189) of the Eastern Han, Lý Tiến was the first native of Jiaozhi to be the inspector of Jiaozhou. Lý Tiến then petitioned the Han emperor to allow natives of Jiaozhi to be officers and mandarins in the Han court, but the emperor only accepted the ones who were awarded maocai (茂才) or xiaolian (孝廉) titles. Another native of Jiaozhi named Lý Cầm petitioned the throne and eventually the natives were allowed to take higher positions in other regions of the Han empire. For example, a Jiaozhi native named Trương Trọng was grand administrator of the Jincheng Commandery.

Three Kingdoms

During the Three Kingdoms period, Jiaozhi was administered from Longbian (Long Biên) by Shi Xie on behalf of the Wu. This family controlled several surrounding commanderies, but upon the headman's death Guangzhou was formed as a separate province from northeastern Jiaozhou and Shi Xie's son attempted to usurp his father's appointed replacement. In retaliation, Wu executed the son and all his brothers and demoted the remainder of the family to common status.

Jin dynasty

Jiaozhi underwent attacks from the neighboring kingdom of Linyi (Champa) starting from 270 and continuing until at least 280. In 280, the governor of Jiaozhi wrote to the emperor of the Western Jin complaining about these attacks aided by allies from the Kingdom of Funan.[22]

Sui dynasty

The Sui divided the commandery into 9 counties: Songping (宋平), Longbian (龍編), Zhuyuan (朱䳒), Longping (隆平), Pingdao (平道), Jiaozhi, Jianing (嘉寧), Xinchang (新昌) and Anren (安人).

Tang dynasty

The Tang first changed Jiaozhi from a commandery to a prefecture (付) named Jiaozhou. Jiaozhi County was created in 622 due to the separation of Songzhou.

In 679, this was renamed Annan (Annam), fully the "Protectorate General to Pacify the South". This comprised 12 prefectures (州), one of which continued under the old name Jiaozhou. This prefecture contained 8 counties: Jiaozhi, Songping, Zhuyuna, Pingdao, Wuping (武平), Nanding (南定), and Taiping (太平).

Medieval Jiaozhi

In 938 Ngô Quyền defeated the Southern Han kingdom at the Battle of Bạch Đằng River north of modern Haiphong. He took Cổ Loa as his capital. In 1257, after invading China in 1251, the Mongol Empire invaded Đại Việt but they had to draw back in 1258 because of local resistance. Between 1284 and 1287, the Mongol Empire tried to invade Đại Việt twice but they were defeated both times.

Ming dynasty

Hồ Quý Ly had violently taken the Trần throne and changed the country's name to Đại Ngu. When the Ming government found out, they demanded that he reestablish the Trần dynasty, which he agreed to. However, Hồ's forces instead ambushed the Ming convoy escorting the Trần pretender, who was killed during the attack, and started harassing the Ming border.[23]

After this, the Ming dynasty invaded Đại Ngu, destroyed the Hồ dynasty, and began the Fourth Northern domination (1407–1427). The Ming created "Jiaozhi Province" (交趾承宣佈政使司). At this time, the Jiaozhi Province area contained all the territory of Vietnam under the Hồ dynasty. The Jiaozhi Province was divided into 15 prefectures (府) and 5 independent prefectures (直隸州):

- 15 prefectures: Jiaozhou (交州), Beijiang (北江), Liangjiang (諒江), Sanjiang (三江), Jianping (建平, Kiến Hưng in Hồ dynasty), Xin'an (新安, Tân Hưng in the Hồ dynasty), Jianchang (建昌), Fenghua (奉化, Thiên Trường in the Hồ dynasty), Qianghua (清化), Zhenman (鎮蠻), Liangshan (諒山), Xinping (新平), Yanzhou (演州), Yian (乂安), Shunhua (順化).

- 5 independent prefectures: Taiyuan (太原), Xuanhua (宣化, Tuyên Quang in the Hồ dynasty), Jiaxing (嘉興), Guihua (歸化), Guangwei (廣威)

Together with the 5 independent prefectures, there were other administrative divisions, which were under the normal prefectures. There were 47 divisions in total.

In 1408, the independent administrative division Taiyuan, Xuanhua was promoted to a prefecture, which increased the number to 17. Afterwards the Yanzhou prefecture was dismissed and its territory became an independent prefecture.

The Ming dynasty crushed Lê Lợi's rebellion at first but indecisively. When Lê had rebuilt his force, the rebel repeatedly defeated Ming's army and tighten their siege of Jiaozhou. Eventually, Ming's emperor accepted the de factor independence of the country. Later, when Lê offered to become a vassal of China, the Ming immediately declared him as ruler of Dai Viet.[24] Lê dismissed all former administrative structure and divided the nation into 5 đạo. Thus, ever since that time, the name Giao Chỉ and Giao Châu have never been applied to official administrative units.

Trade

Jiaozhi and Rinan in what is now northern Vietnam became the main point of entry to China from countries to the west as far away as the Roman Empire, as recorded in the Book of Later Han:

In the ninth Yanxi year [AD 166], during the reign of Emperor Huan, the king of Da Qin [the Roman Empire], Andun (Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, r. 161-180), sent envoys from beyond the frontiers through Rinan... During the reign of Emperor He [AD 89-105], they sent several envoys carrying tribute and offerings. Later, the Western Regions rebelled, and these relations were interrupted. Then, during the second and the fourth Yanxi years in the reign of Emperor Huan [AD 159 and 161], and frequently since, [these] foreigners have arrived [by sea] at the frontiers of Rinan [Commandery in modern central Vietnam] to present offerings.[25]

The Book of Liang states:

The merchants of this country [the Roman Empire] frequently visit Funan [in the Mekong delta], Rinan (Annam) and Jiaozhi [in the Red River Delta near modern Hanoi]; but few of the inhabitants of these southern frontier states have come to Da Qin. During the 5th year of the Huangwu period of the reign of Sun Quan [AD 226] a merchant of Da Qin, whose name was Qin Lun came to Jiaozhi [Tonkin]; the prefect [taishou] of Jiaozhi, Wu Miao, sent him to Sun Quan [the Wu emperor], who asked him for a report on his native country and its people."[26]

The capital of Jiaozhi was proposed by Ferdinand von Richthofen in 1877 to have been the port known to the geographer Ptolemy and the Romans as Kattigara, situated near modern Hanoi.[27] Richthofen's view was widely accepted until archaeology at Óc Eo in the Mekong Delta suggested that site may have been its location. Kattigara seems to have been the main port of call for ships traveling to China from the West in the first few centuries AD, before being replaced by Guangdong.[28]

In terms of archaeological finds, a Republican-era Roman glassware has been found at a Western Han tomb in Guangzhou along the South China Sea, dated to the early 1st century BC.[29] At Óc Eo, then part of the Kingdom of Funan near Jiaozhi, Roman golden medallions made during the reign of Antoninus Pius and his successor Marcus Aurelius have been found.[30][31] This may have been the port city of Kattigara described by Ptolemy, laying beyond the Golden Chersonese (i.e. Malay Peninsula).[30][31]

See also

- Kang Senghui, a Buddhist monk of Sogdian origin who lived in Jiaozhi during the 3rd century

- Tonkin, an exonym for northern Vietnam, approximately identical to the Jiaozhi region

- Cochinchina, an exonym for (southern) Vietnam, yet cognate with the term Jiaozhi

Footnotes

- Chamberlain, James R. (2016). "Kra-Dai and the Proto-History of South China and Vietnam". Journal of the Siam Society. 104.

- Ferlus, Michel (2009). Formation of Ethnonyms in Southeast Asia. 42nd International Conference on Sino-Tibetan Languages and Linguistics, Nov 2009, Chiang Mai, Thailand. 2009, pp. 3-4.

- Pain, Frédéric (2008). An Introduction to Thai Ethnonymy: Examples from Shan and Northern Thai. Journal of the American Oriental Society Vol. 128, No. 4 (Oct. - Dec., 2008), p.646.

- Ferlus, Michel (2009). Formation of Ethnonyms in Southeast Asia. 42nd International Conference on Sino-Tibetan Languages and Linguistics, Nov 2009, Chiang Mai, Thailand. 2009, p.4.

- Ferlus, Michel (2009). Formation of Ethnonyms in Southeast Asia. 42nd International Conference on Sino-Tibetan Languages and Linguistics, Nov 2009, Chiang Mai, Thailand. 2009, p.3.

- Chamberlain, James R. (2000). "The origin of the Sek: implications for Tai and Vietnamese history" (PDF). In Burusphat, Somsonge (ed.). Proceedings of the International Conference on Tai Studies, July 29–31, 1998. Bangkok, Thailand: Institute of Language and Culture for Rural Development, Mahidol University. pp. 97–127. ISBN 974-85916-9-7. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- Schliesinger, Joachim (2018). Origin of the Tai People 5―Cradle of the Tai People and the Ethnic Setup Today Volume 5 of Origin of the Tai People. Booksmango. pp. 21, 97. ISBN 978-1641531825.

- Schliesinger, Joachim (2018). Origin of the Tai People 6―Northern Tai-Speaking People of the Red River Delta and Their Habitat Today Volume 6 of Origin of the Tai People. Booksmango. pp. 3–4, 22, 50, 54. ISBN 978-1641531832.

- Schafer, Edward (1967). The Vermillion Bird. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 58.

- Pulleyblank, E.G. (1983). The Chinese and their neighbors in prehistoric and early historic times. In The Origins of Chinese Civilization, ed. by David N. Knightly, 411-466. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 433.

- Churchman, Michael (2011). "The people in between": The Li and the Lao from the Han to the Sui. In The Tonking Gulf Through History, eds. Nola Cooke, Li Tana, and James Anderson. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 70.

- Ferlus, Michael (2009). "A Layer of Dongsonian Vocabulary in Vietnamese" (PDF). Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society. 1: 95–108.

- Phan, John. 2013. Lacquered Words: the Evolution of Vietnamese under Sinitic Influences from the 1st Century BCE to the 17th Century CE. Ph.D. dissertation: Cornell University.

- Phan, John D. & de Sousa, Hilário. 2016. A preliminary investigation into Proto-Southwestern Middle Chinese. (Paper presented at the International workshop on the history of Colloquial Chinese – written and spoken, Rutgers University, New Brunswick NJ, 11–12 March 2016.)

- Phan, John. "Re-Imagining 'Annam': A New Analysis of Sino–Viet–Muong Linguistic Contact" in Chinese Southern Diaspora Studies, Volume 4, 2010. pp. 22-3

- Ciyuan, volume Tý, page 141.

- Yule, Sir Henry Yule, A. C. Burnell, William Crooke (1995). A glossary of colloquial Anglo-Indian words and phrases: Hobson-Jobson. Routledge. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-7007-0321-0..

- Reid, Anthony (1993), Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, Vol. 2: Expansion and Crisis, New Haven: Yale University Press, p. 211.

- Xiong (2009).

- Đất nước Việt Nam qua các đời, Văn hóa Thông tin publisher, 2005

- "Mê Linh khởi nghĩa". Cổng Thông tin Điện tử Hậu Giang.

- Hall, D.G.E. (1981). A History of South-East Asia, Fourth Edition. Hong Kong: Macmillan Education Ltd. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-333-24163-9.

- Tsai, Shih-shan Henry (2001). Perpetual happiness: The Ming emperor Yongle. Seattle: University of Washington Press. p. 179. ISBN 0-295-98109-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- David C. Kang, Dat X. Nguyen, Ronan Tse-min Fu, Meredith Shaw. "War, Rebellion, and Intervention under Hierarchy: Vietnam–China Relations, 1365 to 1841." Journal of Conflict Resolution 63.4 (2019): 896-922. online

- Hill (2009), pp. 27, 31.

- Hill (2009), p. 292.

- Ferdinand von Richthofen, China, Berlin, 1877, Vol.I, pp.504-510; cited in Richard Hennig,Terrae incognitae : eine Zusammenstellung und kritische Bewertung der wichtigsten vorcolumbischen Entdeckungsreisen an Hand der daruber vorliegenden Originalberichte, Band I, Altertum bis Ptolemäus, Leiden, Brill, 1944, pp.387, 410-411; cited in Zürcher (2002), pp. 30-31.

- Hill 2004 - see: and Appendix: F.

- An, Jiayao. (2002), "When Glass Was Treasured in China," in Annette L. Juliano and Judith A. Lerner (eds), Silk Road Studies VII: Nomads, Traders, and Holy Men Along China's Silk Road, 79–94, Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, ISBN 2503521789, p. 83.

- Gary K. Young (2001), Rome's Eastern Trade: International Commerce and Imperial Policy, 31 BC - AD 305, London & New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-24219-3, pp 29-30

- For further information on Oc Eo, see Milton Osborne (2006), The Mekong: Turbulent Past, Uncertain Future, Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, revised edition, first published in 2000, ISBN 1-74114-893-6, pp 24-25.

References

- Hill, John E. (2009) Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, 1st to 2nd Centuries CE. BookSurge, Charleston, South Carolina. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

- Xiong, Victor Cunrui (2009), "Jiaozhi", Historical Dictionary of Medieval China, Lanham: Scarecrow Press, p. 251, ISBN 978-0-8108-6053-7.

- Zürcher, Erik (2002): "Tidings from the South, Chinese Court Buddhism and Overseas Relations in the Fifth Century AD." Erik Zürcher in: A Life Journey to the East. Sinological Studies in Memory of Giuliano Bertuccioli (1923-2001). Edited by Antonio Forte and Federico Masini. Italian School of East Asian Studies. Kyoto. Essays: Volume 2, pp. 21–43.