Javakheti

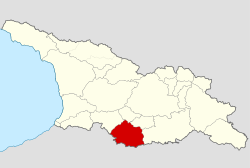

Javakheti (Georgian: ჯავახეთი [dʒɑvɑχɛtʰi]; Armenian: Ջավախք, Javakhk)[2][3] is a historical province in southern Georgia, corresponding to the modern Akhalkalaki and Ninotsminda municipalities. Historically, Javakheti borders in the west to the Kura River (Mtkvari), and in the north, south and east with the Shavsheti, Samsari and Nialiskuri mountains. Principal economic activities in this region are subsistence agriculture, particularly potatoes, and raising livestock.

Javakheti | |

|---|---|

Historical region | |

Map highlighting the historical region of Javakheti in Georgia | |

| Largest city | Akhalkalaki |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2,588 km2 (999 sq mi) |

| Elevation (highest point: Didi Abuli) | 3,300 m (10,800 ft) |

| Population (2014)[1] | |

| • Total | 69,561 |

| • Density | 27/km2 (70/sq mi) |

In 1995, the Akhalkalaki and Ninotsminda districts, comprising the historical territory of Javakheti, was merged with the neighboring land of Samtskhe to form a new administrative region, Samtskhe-Javakheti. Armenians comprise the majority of Javakheti's population. According to the 2014 Georgian census, 93% (41,870) of the inhabitants in Akhalkalaki Municipality and 95% (23,262) in Ninotsminda Municipality were Armenians.[1]

Etymology

In terminology, the name Javakheti is taken from javakh core with traditional Georgian -eti suffix; commonly, Javakheti means the home of Javakhs (an ethnic subgroup of Georgians), as for example, the word Ossetia is taken from Georgian Osi plus -eti. The -k suffix in Armenian has an identical meaning.

The earliest mention of the name was found in Urartu sources, in the notes of king Argishti I of Urartu, 785 BC, as Zabaha.[4]

History

Antiquity

In the sources, the region was recorded as Zabakha in 785 BC, by the king Argishti I of Urartu and, probably, meaning one of the ethnic groups of Urartu. According to Cyril Toumanoff, Javakheti, together with Erusheti, was part of the Iberian duchy of Tsunda from the 4th or 3rd century BC. Since 2nd century BC to 5th century AD this region was a part of an Armenian province - Gugark, in Greater Armenia.

Saint Nino entered Iberia from Javakheti, one of the southern provinces of Iberia, and, following the course of the River Kura, she arrived in Mtskheta, the capital of the kingdom, once there, she eventually began to preach Christianity, which culminated by Christianization of Iberia.

One of the earliest Armenian sources, Faustus of Byzantium (the 5th century) writes: “Maskut King Sanesan, extremely angry, was filled with hate for his tribesman, Armenian King Khosrow, and gathered all of his troops—Huns, Pokhs, Tavaspars, Khechmataks, Izhmakhs, Gats, Gluars, Gugars, Shichbs, Chilbs, Balasich, and Egersvans, as well as an uncountable number of other diverse nomadic tribes, all the numerous troops he commanded. He crossed his border, the great River Kura, and invaded the Armenian country.”[5]

In the 5th century during the rule of Vakhtang I of Iberia Javakheti was a province of Iberia and after his death his second wife the Byzantine princess settled in Tsunda (part of Javakheti).

Middle Ages

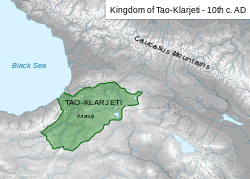

In the struggle against the Arab occupation, Bagrationi dynasty came to rule over Tao-Klarjeti and established the Kouropalatate of Iberia. Rulers of Tao-Klarjeti fought the Arabs from this region, and gradually incorporated surrounding lands of Samtskhe and Javakheti, along with a few other lands, into its territory.

10th century Armenian historian, Ukhtanes, wrote about the family tree of Kyrion, the Catholicos of Iberia. The literal translation of this text is as follows: Kyrion “came from the Iberians in terms of country and lineage, from the region of the Javakhs.” There can be no doubt that Ukhtanes believed Javakheti to be part of Iberia, and the Javakhs to be Iberians . Z. Aleksidze examines the viewpoint of this historian and the enlightened Armenian society of the 10th century on the problem that interests us in depth.[6]

Between 9th-11th centuries part of Javakheti/Javakhk was ruled by Bagratid Armenia. In the mid-10th century, part of Javakheti was incorporated into Kingdom of Abkhazia. In 964 Leon III of Abkhazia extended his influence to Javakheti, and during his reign the Kumurdo Cathedral was built.[7][8] In subsequent centuries, Javakheti remained in the hands of the unified Georgian monarchy and had a period of significant development, during which numerous bridges, churches, monasteries, and royal residences (Lgivi, Ghrtila, Bozhano, Vardzia, etc.) were built. In 1064 the Seljuk Turks conquered the area and ruled over the area until 1118 when the David the Builder liberated the area from the Turks. It then became part of the Principality of Armenia ruled by the Zakarian family, as a vassal state of the Kingdom of Georgia.

In 1245, Javakhketi came under the control of the Toreli feudal family. In 1268, Javakheti was annexed by the principality of Samtskhe-Saatabago, ruled by the House of Jaqeli. In the 1587, the region, along with the entirety of the Principality, was occupied by the Ottoman Empire becoming the Childir Eyalet. The area's population was devastated by the Turco-Mongol incursions. In 1484, Yaqub bin Uzun Hasan of the Aq Qoyunlu devastated the principality. Islam began to spread in the area among both Georgians and Armenians. As the Georgian Church began to lose influence in the area, many Chalcedonian Armenians began to join the Armenian Catholic Church. The Islamized locals began to mix with the Turkic settlers, forming the Meskhetian Turk identity, that became dominant to the west of Javakheti in Meskheti. In 1731 Nader Shah of Afsharid Iran launched an incursion into the Caucasus and during this time enslaved 6,000 Armenians from the Childir Eyalet according to Armenian Catholicos Abraham Kretatsi.

Russian Empire

In the first third of the 19th century, following the Russo-Persian War (1804-1813) and the Russo-Persian War of 1826-1828, Russia conquered the Southern Caucasus, and most of Georgia, along with the rest of the Caucasus, was incorporated within the Russian Empire. When the Russians conquered Javakheti it was home to 1,716 Armenians (67.7%), 639 Muslim (25.2%), and 179 Georgian families (7.1%). Many of the Muslim families chose to resettle in the Ottoman Empire following the Russian annexation of the region. The Tsarist government initiated a plan to resettle its new frontier with Iran and Turkey with Armenians who they deemed to be loyal. In total some 90,000 Armenians from the Ottoman Empire and 40,000 Armenians from Qajar Iran resettled in the Russian Caucasus, primarily the Armenian Oblast.[9] In 1829 some 7,300 Armenian families (58,000 people) resettled in Meskheti, Javakheti, and Trialeti.[10] Armenians moving to Trialeti were joined by Turkish-speaking Caucasus Greeks known as Urums.[11] Armenians moving to Javakheti were joined by a number of Doukhobors, a spiritual Christian sect from Russia. In the early 20th century, a large number of Armenian refugees from the Armenian genocide in the Ottoman Empire, and Doukhobor sect members of Russian Empire, settled the region.

An 1886 report found 63,799 people living in Javakheti, of which 46,384 were Armenians (72.7%), 6,674 Russians (10.5%), 6,091 Turks (9.5%), and 3,741 Georgians (5.9%). The Russian Empire Census of 1897 found 72,709 people in Javakheti, of which 52,539 were Armenians (72.3%), 6,868 were Turks (9.4%), 6,448 were Georgians, and 5,155 were Russians (7.1%).

Soviet era

Georgia came fully under Soviet control in 1921, and Javakheti, along with other former Georgian territories, became part of the Georgian SSR. The remaining Muslim minority in Javakheti, also known as "Meskhetian Turks", were deported to Uzbekistan in 1944 during the regime of Stalin.[9]

Current situation

An expected improvement is the planned construction of the highway (financed by the US Millennium Challenge Account) to more effectively link the region with the rest of Georgia. Also, a railroad is planned to run from Kars, Turkey to Baku, Azerbaijan via the area (see: Kars Baku Tbilisi railway line), but the Armenian population of Javakheti are opposed to this rail link because it excludes and isolates Armenia. There is already another railroad linking Armenia, Georgia and Turkey, which is the Kars-Gyumri-Akhalkalaki railroad line. The existing line is in working condition and could be operational within weeks, but due to the Turkish blockade of Armenia since 1993, the railroad is not operational.

See also

- Armenians in Georgia

- Armenians in Samtskhe-Javakheti

References

- "Population Census 2014". www.geostat.ge. National Statistics Office of Georgia. November 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- Rezvani, Babak (2014). Conflict and Peace in Central Eurasia: Towards Explanations and Understandings. BRILL. p. 1. ISBN 9789004276369.

...Javakheti (called Javakhk by Armenians).

- "Georgian Court Sentences Armenian Activist To 10 Years In Prison". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 8 April 2009.

...Georgian region of Javakheti (Armenian Javakhk)...

- Melkonyan, Ashot (2007). Javakhk in the 19th century and the 1st quarter of the 20th century : a historical research. Erevan: National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Armenia, Institute of History. p. 36. ISBN 978-9994173075.

- ИСТОРИЯ АРМЕНИИ [History of Armenia] (in Russian). Yerevan, Armenian SSR: Academy of Sciences of Armenian SSR. 1953.

- http://www.ca-c.org/c-g/2011/journal_eng/c-g-1-2/13.shtml#nazad43

- "Kumurdo Church". Georgian patriarchate, Eparchy of Shemoqmedi. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- "Kumurdo". Parliament of Georgia. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- Moshe Gammer (25 June 2004). The Caspian Region, Volume 2: The Caucasus. Routledge. pp. 24–. ISBN 978-1-135-77541-4.

- Migration of Armenians (Russian).

- Boeschoten, Hendrik; Rentzsch, Julian (2010). Turcology in Mainz. p. 142. ISBN 978-3-447-06113-1. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20110708124400/http://www.caucaz.com/home_eng/breve_contenu.php?id=235. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved February 10, 2011. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

Bibliography

- Lalayan, Yervand (1895). Ջաւախք [Javakhk'] (in Armenian). Azgagrakan Handes [Ethnographic Review].

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Javakheti. |