James Gordon Bennett Sr.

James Gordon Bennett Sr. (September 1, 1795 – June 1, 1872) was the founder, editor and publisher of the New York Herald and a major figure in the history of American newspapers.

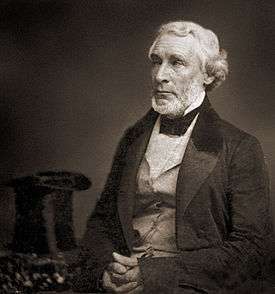

James Gordon Bennett Sr. | |

|---|---|

Bennett c. 1851 | |

| Born | September 1, 1795 |

| Died | June 1, 1872 (aged 76) Manhattan, New York City, U.S. |

| Occupation | Publisher |

| Known for | Founder of New York Herald |

| Spouse(s) | Henrietta Agnes Crean (m. 1840; his death 1872) |

| Children | 3, including James Jr. |

Early life

Bennett was born to a prosperous Roman Catholic family in Newmill, Banffshire, Scotland, Great Britain. At age 15, Bennett entered the Roman Catholic seminary in Aberdeen, where he remained for four years.[1] After leaving the seminary, he read voraciously on his own and traveled throughout Scotland.

In 1819, he joined a friend who was sailing to North America. After four weeks they landed in Halifax, Nova Scotia, where Bennett briefly worked as a schoolmaster till he had enough money to sail south to Portland, Maine, where he again taught school in the village of Addison, moving on to Boston, Massachusetts by New Year's Day, 1820.[1] He worked in New England as a proofreader and bookseller before the Charleston Courier in Charleston, South Carolina hired him to translate Spanish language news reports, so he briefly relocated to The South. He moved back north to New York City in 1823, where he worked first as a freelance paper writer and, then, assistant editor of the New York Courier and Enquirer, one of the oldest newspapers in the city.[2]

New York Herald

In May 1835, Bennett began the New York Herald after years of failing to start a paper. After only a year of publication, in April 1836, it shocked readers with front–page coverage of the grisly murder of prostitute Helen Jewett; Bennett got a scoop and conducted the first-ever newspaper interview for it. In business and circulation policy, The Herald initiated a cash–in–advance policy for advertisers, which later became the industry standard. Bennett was also at the forefront of using the latest technology to gather and report the news, and added pictorial illustrations produced from woodcuts. In 1839, Bennett was granted the first ever exclusive interview to a sitting President of the United States, the eighth occupant, Martin Van Buren (1782–1862, served 1837–1841).[3]

Endorsements

The Herald was officially independent in its politics, but endorsed for President in turn William Henry Harrison (1840), James K. Polk (1844), Zachary Taylor (1848), Franklin Pierce (1852), and John C. Frémont (1856). Author Garry Boulard speculates that Bennett ultimately turned against Franklin Pierce after the 14th President failed to appoint him to a much-coveted post as American minister plenipotentiary (later called ambassador) to France. From that point on, Bennett consistently lambasted President Pierce on both his front and editorial page, often calling him "Poor Pierce." Bennett supported Democrat and Secretary of State under Pierce, James Buchanan of Pennsylvania in the 1856 Election as tensions rose between the sections and states over slavery and states' rights and reached critical point during the 1850s, after the controversial Compromise of 1850.

He later endorsed Southerner Democrat and incumbent Vice President John C. Breckinridge (1821–1875, served 1857–1861), of Kentucky under Buchanan for the 1860 presidential campaign, then shifted to John Bell (1796–1869), of Tennessee running as a Constitutional Unionist among the four presidential candidates in the confused but pivotal general election in November 1860. During the midst of the following Civil War (1861–1865), he promoted former Union Army General-in-Chief George B. McClellan (1826-1885), nominated from the Democratic Party in the 1864 election, campaigning for a negotiated peace with the South against a second term for wartime 16th President Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865, served 1861–1865), but the paper itself endorsed no candidate for the unusual war election of 1864.

Although he generally opposed Republican Abraham Lincoln, Bennett still backed the Northern cause with the Union, then took the lead to turn the Republican war president into a martyr after his April 14, 1865 assassination at Ford's Theater in Washington. He favored most of successor 17th President Andrew Johnson (1808–1875, served 1865–1869), former Vice President for one month in Lincoln's brief second term, a War Democrat, former U.S. Senator and loyal wartime Governor of Tennessee, and his following moderate Reconstruction Era policies and proposals towards the defeated South, following what was thought would have been President Lincoln's gentle hand had he lived.

Later career

By the time Bennett turned control of the New York Herald over to his son James Gordon Bennett Jr. (1841–1912), at age 25 in 1866, it had the highest circulation in America but would soon face increasing competition from Greeley's Tribune and soon in the next decades, from Joseph Pulitzer's New York World, William Randolph Hearst's New York Journal, along with Henry J. Raymond's The New York Times. However, under the younger Bennetts' stewardship, the paper slowly declined under the increasing stiff competition and changing technologies in the late 19th century and, after his 1912 death, it was merged a decade later with its former arch-rival, the New York Tribune in 1924, becoming the New York Herald Tribune for another 42 years meeting with considerable success and reputation in its near last half-century, until finally closing in 1966–1967.

Personal life

On June 6, 1840 he married Henrietta Agnes Crean in New York. They had three children, including:

- James Gordon Bennett, Jr. (1841–1918)

- Jeanette Gordon Bennett (d. 1936), who married Isaac Bell Jr. (1846–1889)

He died in Manhattan, New York City, on June 1, 1872.[4] This was five months before his rival / competitor Horace Greeley also succumbed to illness in November 1872, after Greeley's disastrous presidential election campaign of 1872.[5] He was interred at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York City.[6]

Legacy

According to historian Robert C. Bannister, Bennett was :

- A gifted and controversial editor. Bennett transformed the American newspaper. Expanding traditional coverage, the Harold provided sports reports, a society page, and advice to the lovelorn, soon permanent features of most metropolitan dailies. Bennett covered murders and sex scandals and delicious detail, faking materials when necessary.... His adroit use of telegraph, pony express, and even offshore ships to intercept European dispatches set high standards for rapid news gathering.[7] Bannister also argues that he was a leading crusader in American election campaigns in the 19th century:

- Combining opportunism and reform, Bennett exposed fraud on Wall Street, attacked the Bank of the United States, and generally joined the Jacksonian assault on privilege. Reflecting a growing nativism, he published excerpts from the anti-catholic disclosures of "Maria Monk," and he greeted Know-Nothingism cordially. Defending labor unions in principle, he asssailed much union activity. Unable to condemn slavery outright, he opposed abolitionism.[8]

It was noted that James Gordon Bennett was cross eyed for most of his life, an acquaintance once said that he was "so terribly cross-eyed that when he looked at me with one eye, he looked out at the City Hall with the other."[9]

The phrase "Gordon Bennett" which denotes exasperation or shock derives from the son, or amongst the FDNY (New York Fire Department) where it is the highest medal a New York City Firefighter can earn (compared to the Congressional Medal of Honor for the U.S. military), "That meal was so good, it should win the Gordon Bennett!" (See also the various Gordon Bennett Cups).

He has a street named for him from West 181st Street to Hillside Avenue in the Washington Heights neighborhood of northern Manhattan, and a New York City park, Bennett Park named in his honor along Fort Washington Avenue. The Avenue Gordon Bennett in Paris, France with Stade de Roland Garros, site of the French Open, tennis tournament, is also named after James Gordon Bennett, Sr., possibly thanks to his son.[10]

Bennett's account of the infamous Helen Jewett murder in the Herald was selected by The Library of America for inclusion in the 2008 anthology True Crime.

Notes

- Notes

- James L. Crouthamel (1989). Bennett's New York Herald and the Rise of the Popular Press. Syracuse University Press.

- Harrison, Robert (1885). . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. 4. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Paletta, Lu Ann and Worth, Fred L. (1988). "The World Almanac of Presidential Facts".

- "James Gordon Bennett" (PDF). New York Times. June 2, 1872.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 740–741.

- "Mr. Bennett's Funeral. Imposing Ceremonies at the House Father Siarrs' Oration. The Remains Taken to Green-Wood". New York Times. June 14, 1872.

- Robert C. Bannister, "Bennett, James Gordon" in John A. Garraty, ed., Encyclopedia of American Biography (1975) pp. 80-81.

- Bannister, "Bennett, James Gordon" pp. 80-81.

- "Bennett, James Gordon (1795-1872)". Encyclopedia of Communication and Information. Archived from the original on January 23, 2019.

- Invisible Paris: see street sign

- Sources

- Carlson, Oliver. The Man Who Made News: James Gordon Bennett. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1942

- Crouthamel, James L. Bennett's New York Herald and the Rise of the Popular Press. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1989 Online