Ivory-billed woodpecker

The ivory-billed woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) is one of the largest woodpeckers in the world, at roughly 20 inches (51 cm) long and 30 inches (76 cm) in wingspan. It is native to the bottomland hardwood forests and temperate coniferous forests of the Southeastern United States and Cuba. Habitat destruction, and to a lesser extent, hunting has reduced populations so thoroughly that the species is listed as critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature,[1] and the American Birding Association lists the ivory-billed woodpecker as a class 6 species, a category it defines as "definitely or probably extinct".[3] The last universally accepted sighting of an American ivory-billed woodpecker occurred in Louisiana in 1944. However, sporadic reports of sightings and other evidence of the birds' persistence have continued ever since. In the 21st century, reported sightings and analyses of audio and visual recordings have been published in peer-reviewed scientific journals as evidence that the species persists in Arkansas, Louisiana, and Florida. Various land purchases and habitat restoration efforts have been initiated in areas where sightings and other evidence have suggested a relatively high probability the species exists, to protect any surviving individuals.

| Ivory-billed woodpecker | |

|---|---|

| |

| A male ivory-billed woodpecker leaving the nest as the female returns. Taken on the Singer Tract, Louisiana, April 1935, by Arthur A. Allen | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Piciformes |

| Family: | Picidae |

| Genus: | Campephilus |

| Species: | C. principalis |

| Binomial name | |

| Campephilus principalis | |

| Subspecies | |

|

Campephilus p. principalis | |

| |

| Estimated range of the ivory-billed woodpecker by Edwin Hasbrouck; Pre-1860 (Solid Line), 1891 (Hatched Area) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Picus principalis Linnaeus, 1758 | |

Taxonomy

The ivory-billed woodpecker was first described as Picus maximus rostra albo "the largest white-bill woodpecker" in English naturalist Mark Catesby's 1731 publication of Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahamas.[4][lower-alpha 1] Noting his report, Linnaeus later described it in the landmark 1758 10th edition of his Systema Naturae, where it was given the binomial name of Picus principalis.[6] The genus Campephilus was introduced by the English zoologist George Robert Gray in 1840 with the ivory-billed woodpecker as the type species.[7]

Ornithologists currently recognize two subspecies of this bird:

- American ivory-billed woodpecker (Campephilus principalis principalis or Campephilus principalis), native to the Southeastern United States

- Cuban ivory-billed woodpecker (Campephilus principalis bairdii or Campephilus bairdii), native to Cuba

The two look similar, with the Cuban bird somewhat smaller[8] and some variations in plumage with the white dorsal strips extending to the bill, and the red crest feathers of the male longer than its black crest feathers, while the two are of the same length in the American subspecies.[9]

Some controversy exists over whether the Cuban ivory-billed woodpecker is more appropriately recognized as a separate species. A recent study compared DNA samples taken from specimens of both ivory-billed birds, along with the imperial woodpecker, a larger but otherwise very similar bird. It concluded not only that the Cuban and American ivory-billed woodpeckers are genetically distinct, but also that they and the imperial form a North American clade within Campephilus that appeared in the mid-Pleistocene.[10] The study does not attempt to define a lineage linking the three birds, though it does imply that the Cuban bird is more closely related to the imperial.[10] The American Ornithologists' Union Committee on Classification and Nomenclature has said it is not yet ready to list the American and Cuban birds as separate species. Lovette, a member of the committee, said that more testing is needed to support that change, but concluded, "These results will likely initiate an interesting debate on how we should classify these birds."[11]

"Ivory-billed woodpecker" is the official name given to the species by the International Ornithologists' Union.[12] The ivory-billed woodpecker is sometimes referred to as the "holy grail bird" (because of its rarity and elusiveness) and the "Lord God bird" or the "Good God bird" (both based on the exclamations of awed onlookers).[13] Other nicknames for the bird are the "King of the Woodpeckers" and "Elvis in Feathers".[14] Older common names included Indian Hen, Poule de Bois (in Cajun French), Tit-ka (in Seminole), and Log-cock.[15]

Description

The ivory-billed woodpecker is the largest woodpecker in the United States. The closely related imperial woodpecker (C. imperialis) of western Mexico, though also regarded as extinct, is the largest woodpecker in the world. The ivory-billed has a total length of 48 to 53 cm (19 to 21 in), and based on scant information, weighs about 450 to 570 g (0.99 to 1.26 lb). It has a typical 76 cm (30 in) wingspan. Standard measurements attained included a wing chord length of 23.5–26.5 cm (9.3–10.4 in), a tail length of 14–17 cm (5.5–6.7 in), a bill length of 5.8–7.3 cm (2.3–2.9 in), and a tarsus length of 4–4.6 cm (1.6–1.8 in).[16]

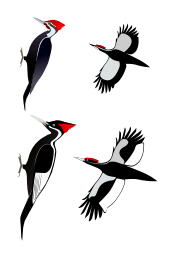

The bird is sexually dimorphic, as seen in the picture to the right. It is shiny blue-black with white markings on its neck and back and extensive white on the trailing edge of both the upper- and underwing. The underwing is also white along its forward edge, resulting in a black line running along the middle of the underwing, expanding to more extensive black at the wingtip. In adults, the bill is ivory in color, and chalky white in juveniles. Ivory-bills have a prominent crest, although in juveniles it is ragged. The crest is black in juveniles and females. In males, the crest is black along its forward edge, changing abruptly to red on the side and rear. The chin of an ivory-billed woodpecker is black. When perched with the wings folded, birds of both sexes present a large patch of white on the lower back, roughly triangular in shape. These characteristics distinguish them from the smaller and darker-billed pileated woodpecker. The pileated woodpecker normally is brownish-black, smoky, or slaty black in color. It also has a white neck stripe, but the back is normally black. Pileated woodpecker juveniles and adults have a red crest and a white chin. Pileated woodpeckers normally have no white on the trailing edges of their wings and when perched, normally show only a small patch of white on each side of the body near the edge of the wing. However, pileated woodpeckers, apparently aberrant individuals, have been reported with white trailing edges on the wings, forming a white triangular patch on the lower back when perched. Like all woodpeckers, the ivory-billed woodpecker has a strong and straight bill and a long, mobile, hard-tipped, barbed tongue. Among North American woodpeckers, the ivory-billed woodpecker is unique in having a bill whose tip is quite flattened laterally, shaped much like a beveled wood chisel. Overall it is a very large and distinctive woodpecker with a charismatic, very clean and smooth appearance.

The bird's drum is a single or double rap. Four fairly distinct calls are reported in the literature and two were recorded in the 1930s. The most common, a kent or hant, sounds like a toy trumpet often repeated in a series. When the bird is disturbed, the pitch of the kent note rises, it is repeated more frequently, and it is often doubled. A conversational call, also recorded, is given between individuals at the nest, and has been described as kent-kent-kent. A recording of the bird, made by Arthur A. Allen, can be found here.

Habitat and diet

No attempts to comprehensively estimate the range of the ivory-billed woodpecker were made until after its range had already been severely reduced by deforestation and hunting. The first range map produced for the bird was made by Edwin M. Hasbrouck in 1891.[17] The second range map produced was that made by James Tanner in 1942.[18] Both authors reconstructed the original range of the bird from historical records they considered reliable, in many cases from specimens with clear records of where they were obtained. The two authors produced broadly similar range estimates, finding that before deforestation and hunting began to shrink its range, the ivory-billed woodpecker had ranged from eastern Texas to North Carolina, and from southern Illinois to Florida and Cuba,[19] typically from the coast inland to where the elevation is around 30 m.[20]

A few significant differences in their reconstructions exist. Hasbrouck's range map extended up the Missouri River to around Kansas City based on the reports of Wells Woodbridge Cooke from Kansas City and Fayette,[21] which Tanner rejected as a possible accidental or unproven report.[22] Similarly, Hasbrouck's range estimate extended up the Ohio river valley to Franklin county, Indiana based on a record from the E. T. Cox,[23] which Tanner likewise rejected as unproven or accidental. Tanner's range estimate extended further up the Arkansas River and Canadian River, on the basis of reports of the birds by S. W. Woodhouse west of Fort Smith, Arkansas, and Edwin James at the falls of the Canadian River,[24] which were unmentioned by and possibly unknown to Hasbrouck. Tanner's range map is now generally accepted as the original range of the bird,[18] but a number of records exist outside of both ranges, that were either overlooked or rejected by Tanner, or that surfaced after his analysis. Southwest of Tanner's range estimate, the bird was reported along the San Marcos River and Guadalupe River, as well as near New Braunfels, around 1900.[25] Farther along the Ohio River Valley, William Fleming reported shooting an ivory-billed woodpecker at Logan's Fort, Kentucky in 1780.[26] Ivory-billed woodpecker remains were found in middens in Scioto County, Ohio, which were inferred to come from a bird locally hunted,[27] and similar inferences were drawn from remains found near Wheeling, West Virginia.[28] There is also a report of a bird shot and eaten in Doddridge county, West Virginia around 1900.[29] Along the Atlantic Coast, Hasbrouck set the northern limit of the range around Fort Macon, North Carolina based on reports that did not include specimens,[30] which was rejected as unproven by Tanner, who used the record of a bird shot 12 miles north of Wilmington, North Carolina by Alexander Wilson to set the northern limit of the range.[22]

Records exist of the bird farther along the Atlantic Coast; Thomas Jefferson included it as a bird of Virginia in Notes on the State of Virginia,[31] Audubon reported the bird could occasionally be found as far north as Maryland,[32] and Pehr Kalm reported it was present seasonally in Swedesboro, New Jersey in the mid-18th century.[33] Farther inland, Wilson reported shooting an ivory-bill west of Winchester, Virginia.[29] Bones recovered from the Etowah Mounds in Georgia are generally believed to come from birds hunted locally.[25] Within its range, the ivory-billed woodpecker is not smoothly distributed, but highly locally concentrated in areas where the habitat is suitable and where large quantities of appropriate food can be found.[18]

Knowledge of the ecology and behavior of ivory-billed woodpeckers is largely derived from James Tanner's study of several birds in a tract of forest along the Tensas River in the late 1930s. The extent to which those data can be extrapolated to ivory-bills as a whole remains an open question.[34] Ivory-billed woodpeckers are known to prefer thick hardwood swamps and pine forests, with large numbers of dead and decaying trees. After the Civil War, the timber industry deforested millions of acres in the South, leaving only sparse, isolated tracts of suitable habitat.

The preferred food of the ivory-billed woodpecker is beetle larvae, with roughly half of recorded stomach contents composed of large beetle larvae, particularly of species from the family Cerambycidae,[35] with Scolytidae beetles also recorded.[36] The bird also eats significant vegetable matter, with recorded stomach contents including the fruit of the southern magnolia, pecans,[35] acorns,[36] hickory nuts, and poison ivy seeds.[37] They have also been observed to feed on wild grapes, persimmons, and hackberries[38] To hunt woodboring grubs, the bird uses its enormous bill to hammer, wedge, and peel the bark off dead trees to access their tunnels. These birds need about 25 km2 (9.7 sq mi) per pair to find enough food to feed their young and themselves. Hence, they occur at low densities even in healthy populations.

Breeding biology and lifecycle

The ivory-billed woodpecker is thought to mate for life. Pairs are also known to travel together. These paired birds mate every year between January and May. Both parents work together to excavate a cavity in a tree about 15–70 feet (4.6–21.3 m)[39] from the ground before they have their young, with the limited data indicating a preference for living trees,[40] or partially dead trees, with rotten ones avoided.[39] Nest cavities are typically in or just below broken off stumps in living trees, where the wood is easier to excavate, and the overhanging stump can provide protection against rain and leaving the opening in shadow, providing some protection against predators.[41] There are no clear records of nest cavities being reused, and ivory-bills, like most woodpeckers, likely excavate a new nest each year.[42] Nest openings are typically oval to rectangular in shape, and measure about 12–14 cm tall by 10 cm wide (4.7 in–5.5 in × 3.9 in). The typical nest depth is roughly 50 cm (20 in), with nests as shallow as 36 cm (14 in) and as deep as 150 cm (59 in) reported.[43]

Eggs are typically laid in April or May, with a few records of eggs laid as early as mid-February.[44] A second clutch has only been observed when the first one failed.[45] Typically, up to three glossy, china-white eggs are laid, measuring on average 3.5 cm by 2.5 cm (1.38 in × 0.98 in),[36] though clutches of up to six eggs, and broods of up to four young, have been observed.[46] No nest has been observed for the length of incubation so it remains unknown,[47] though Tanner estimated it to be roughly 20 days.[48] Parents incubate the eggs cooperatively, with the male observed to incubated overnight, and the two birds typically exchanging places every two hours during the day, with one foraging and one incubating. Once the young hatch, both parents forage to bring food to them.[49] Young learn to fly about 7 to 8 weeks after hatching. The parents continue feeding them for another two months. The family eventually splits up in late fall or early winter.

Ivory-billed woodpeckers are not migratory, and pairs are frequently observed to nest within a few hundred meters of previous nests year after year.[45] Although ivory-billed woodpeckers thus feed within a semiregular territory within a few kilometers of their nest/roost, they are not territorial; no records are known of ivory-bills protecting their territories from other ivory-bills when encountering one another.[50] Indeed, in many instances the ivory-billed woodpecker has been observed acting as a social bird, with groups of four or five feeding together on a single tree, and as many as 11 observed feeding in the same location.[51] Similarly, ivory-billed woodpeckers have been observed feeding on the same tree as the only other large woodpecker with which they share a range, the pileated woodpecker, without any hostile interactions.[52] Although not migratory, the ivory-billed woodpecker is sometimes described as nomadic;[53] birds relocate from time to time to areas where disasters such as fires or floods have created large amounts of dead wood, and subsequently large numbers of beetle larva upon which they prefer to feed.[18]

Ornithologists speculate that they may live as long as 30 years.[54]

Status

Heavy logging activity exacerbated by hunting by collectors devastated the population of ivory-billed woodpeckers in the late 19th century. It was generally considered extremely rare, and some ornithologists believed it extinct by the 1920s. In 1924, Arthur Augustus Allen found a nesting pair in Florida, which local taxidermists shot for specimens.[55] In 1932, a Louisiana state representative, Mason Spencer of Tallulah killed an ivory-billed woodpecker along the Tensas River and took the specimen to his state wildlife office in Baton Rouge.[56] As a result, Arthur Allen, fellow Cornell Ornithology professor Peter Paul Kellogg, PhD student James Tanner, and avian artist George Miksch Sutton organized an expedition to that part of Louisiana as part of a larger expedition to record images and sounds of endangered birds across the United States.[55] The team located a population of woodpeckers in Madison Parish in northeastern Louisiana, in a section of the old-growth forest called the Singer tract, owned by the Singer Sewing Company, where logging rights were held by the Chicago Mill and Lumber Company. The team made the only universally accepted audio and motion picture recordings of the ivory-billed woodpecker.[57] The National Audubon Society attempted to buy the logging rights to the tract so the habitat and birds could be preserved, but the company rejected their offer. Tanner spent 1937-1939 studying the ivory-billed woodpeckers on the Singer tract and travelling across the southern United States searching for other populations as part of his thesis work. At that time, he estimated there were 22-24 birds remaining, of which 6-8 were on the Singer tract. The last universally accepted sighting of an ivory billed woodpecker in the United States was made on the Singer tract by Audubon Society artist Don Eckelberry in April 1944,[58] when logging of the tract was nearly complete.[59]

The ivory-billed woodpecker was listed as an endangered species on March 11, 1967, by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service. The ivory-billed woodpecker has been assessed as critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources.[1] It is categorized as probably or actually extinct by the American Birding Association.[60]

Evidence of persistence past 1944

Since 1944, regular reports have been made of ivory-billed woodpeckers being seen or heard across the southeastern United States, particularly in Louisiana, Florida, Texas, and South Carolina.[61] In many instances, sightings were clearly misidentified pileated woodpeckers or red-headed woodpeckers. Similarly, in many cases, reports of hearing the kent call of the ivory-billed woodpecker were misidentifications of a similar call sometimes made by blue jays.[25] It may also be possible to mistake wing collisions in flying duck flocks for the characteristic double knock.[62] However, a significant number of reports were accompanied by physical evidence or made by experienced ornithologists and could not be easily dismissed.[25]

In 1950, the Audubon Society established a wildlife sanctuary along the Chipola River after a group led by University of Florida graduate student Whitney Eastman reported a pair of ivory-billed woodpeckers with a roost hole.[63][64] The sanctuary was terminated in 1952 when the woodpeckers could no longer be located.[65]

In 1967, ornithologist John Dennis, sponsored by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, reported sightings of ivory-billed woodpeckers along the Neches River in Texas.[66] Dennis had previously rediscovered the Cuban species in 1948.[8] Dennis produced audio recording of possible kent calls, which were found to be a good match to ivory-billed woodpecker calls, but possibly also compatible with blue jays.[67] At least 20 people reported sightings of one or more ivory-billed woodpeckers in the area in the late 1960s,[68] and several photographs ostensibly showing an ivory-billed woodpecker in a roost were produced by Neil Wright,[69][70] copies of two of which were given to Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University.[25] These sightings formed part of the basis for the creation of the Big Thicket National Preserve.[71][72]

H. N. Agey and G. M. Heinzmann reported observing one or two ivory-billed woodpeckers in Highlands County, Florida, on 11 occasions from 1967 to 1969.[73] A tree the birds had been observed roosting in was damaged during a storm, and they were able to obtain a feather from the roost, which was identified as an inner secondary feather of an ivory-billed woodpecker by A. Wetmore. The feather is stored at the Florida Museum of Natural History.[39] The feather was described as "fresh, not worn", but as it could not be conclusively dated, it has not been universally accepted as proof ivory-billed woodpeckers persisted to this date.[25]

Louisiana State University museum director George Lowery presented two photos at the 1971 annual meeting of the American Ornithologists Union that show what appeared to be a male ivory-billed woodpecker. The photos were taken by outdoorsman Fielding Lewis in the Atchafalaya Basin of Louisiana, with an Instamatic camera.[74] Although the photos had the correct field markings for an ivory-billed woodpecker, their quality was not sufficient for other ornithologists to be confident they did not depict a mounted specimen, and they were greeted with general skepticism.[75]

In 1999, a Louisiana State University forestry student reported an extended viewing of a pair of birds at close range in the Pearl River region of southeast Louisiana, which some experts found very compelling.[76] In 2002, a large collaboration was organized, and sent an expedition into the area by researchers from Louisiana State University and Cornell University, funded by Carl Zeiss Sports Optics, Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the U.S. Forest Service.[77] Six researchers spent 30 days searching the area, finding indications of large woodpeckers, but none that could be clearly ascribed to ivory-billed woodpeckers rather than pileated woodpeckers.[78]

Gene Sparling reported seeing an ivory-billed woodpecker in Cache River National Wildlife Refuge in 2004, prompting Tim Gallagher and Bobby Harrison to investigate, who also observed a bird they identified as an ivory-billed woodpecker. An expedition led by John W. Fitzpatrick of the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology followed, which reported seven convincing sightings of an ivory-billed woodpecker. The team also heard and recorded possible double-knock and kent calls, and produced a video with four seconds of footage of a large woodpecker, which they identified as an ivory-billed woodpecker due to its size, field marks, and flight pattern.[79] The sighting was accepted by the Bird Records Committee of the Arkansas Audubon Society.[80] The Nature Conservancy and Cornell University bought 120,000 acres (490 km2) of land to enlarge the protected areas that housed suitable habitat.[59] A second search in 2005-2006 produced no unambiguous encounters with ivory-billed woodpeckers. The collaboration subsequently conducted searches in Arkansas, Florida, Illinois, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas, but found no clear indications of ivory-billed woodpeckers in any of those searches,[25] at which point they concluded their efforts.[81] A team headed by David A. Sibley published a response arguing the bird in the video could have a morphology consistent with a pileated woodpecker,[82] and a second team argued the flight characteristics may not be diagnostic.[83] The original team published a rebuttal,[84] and the identity of the bird in the video remains disputed.

Scientists from Auburn University and the University of Windsor published a paper describing a search for ivory-billed woodpeckers along the Choctawhatchee River from 2005–2006, during which they recorded 14 sightings of ivory-billed woodpeckers, 41 occasions on which double-knocks or kent calls were heard, 244 occasions on which double-knocks or kent calls were recorded, and analysis of those recordings, and of tree cavities and bark stripping by woodpeckers they found consistent with the behavior of ivory-billed woodpeckers, but inconsistent with the behavior of pileated woodpeckers.[85] In 2008, the sightings and sound detections largely dried up, and the team ended their searches in 2009.[86] The sightings were not accepted by the Florida Ornithological Society Records Committee.[87]

Mike Collins, a scientist from the Naval Research Laboratory, reported 10 sightings of ivory-billed woodpeckers between 2006 and 2008, obtained video evidence in the Pearl River in 2006 and 2008 and the Choctawhatchee River in 2007, explored the use of drones for searching and surveying habitats, and analyzed the elusiveness and double knocks of this species.[88][89][90][91][92] Avian artist Julie Zickefoose contributed to the analysis of the 2006 video, which is based on behaviors, neck/crest/bill morphology, and a size comparison with a pileated woodpecker specimen mounted on the perch tree.[88][89][92] Ornithologist Bret Tobalske contributed to the analysis of the 2008 video, which is based on woodpecker flight mechanics, wing motion, flap rate, flight speed, wing shape, and field marks.[88][89][92] The 2007 video shows a series of events involving swooping flights with long, vertical ascents, deep and rapid flaps at takeoff, a double knock that is visible and audible, and other behaviors and characteristics that are consistent with the ivory-billed woodpecker, but apparently no other species of the region.[89][92] These reports (like all others since 1944) have been received with skepticism.[93] The ivory-billed woodpecker's history of elusiveness (multiple claimed rediscoveries with no clear photo during the past several decades) is consistent with an analysis based on behavior and habitat that suggests the expected waiting time for obtaining a clear photo is several orders of magnitude greater than it would be for a more typical species of comparable rarity.[89][92] However, many have argued that the inability to get a clear photo for decades is consistent with extinction. An analysis based on the concept of a harmonic oscillator relates the double knocks of the ivory-billed woodpecker (and double/multiple knocks of other Campephilus woodpeckers) to the drumming that is typical of most woodpeckers.[90]

Relationship with humans

Ivory-billed body parts, particularly bills, were sometimes used for trade, ceremonies, and decoration by some Native American groups from the western Great Lakes and Great Plains regions.[94] For instance, bills marked with red pigment were found among grave goods in burials at Ton won tonga, a village of the Omaha people. The bills may have been part of Wawaⁿ Pipes.[95] Ivory-billed woodpecker bills and scalps were commonly incorporated into ceremonial pipes by the Iowa people, another Siouan-speaking people.[94] The Sauk people and Meskwaki used ivory-billed body parts in amulets, headbands, and sacred bundles.[94] In many cases, the bills were likely acquired through trade; for instance, Ton won tonga was located roughly 300 miles from the farthest reported range of the ivory-billed woodpecker, and the bills were only found in the graves of wealthy adult men,[95] and one bill was found in a grave in Johnstown, Colorado.[96] The bills were quite valuable, with Catesby reporting a north–south trade where bills were exchanged outside the bird's range for two or three deerskins.[4] European settlers in the United States also used ivory-bills' remains for adornment, often securing dried heads to their shot pouches, or employing them as watch fobs.[97]

The presence of ivory-bills' remains in kitchen middens has been used to infer that some Native American groups would hunt and eat the bird.[27] Such remains have been found in Illinois, Ohio,[98] West Virginia, and Georgia.[25] The hunting of ivory-billed woodpeckers for food by the residents of the Southeastern United States continued into the early 20th century,[99] with reports of hunting ivory-billed woodpeckers for food continuing until at least the 1950s.[63] In some instances, the flesh of ivory-billed woodpeckers was used as bait by trappers and fishermen.[99][70] In the nineteenth and into the early twentieth century, hunting for bird collections was extensive, with 413 specimens now housed in museum and university collections.[100] The largest collection is that of more than 60 skins at the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology.[101]

The ivory-billed woodpecker has been a particular focus among birdwatchers. It has been called Audubon's favorite bird.[102] Roger Tory Peterson called his unsuccessful search for the birds along the Congaree River in the 1930s his "most exciting bird experience".[103] After the publication of the Fitzpatrick results, tourist attention was drawn to eastern Arkansas, with tourist spending up 30% in and around the city of Brinkley, Arkansas. Brinkley hosted "The Call of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker Celebration" in February 2006. The celebration included exhibits, birding tours, educational presentations, and a vendor market.[104] By the twenty-first century, the ivory-billed woodpecker had achieved a near-mythic status among birdwatchers, most of whom would regard it as a prestigious entry on their life lists.[105]

The ivory-billed woodpecker has been the subject of various artistic works. Sufjan Stevens wrote a song titled "The Lord God Bird" on the ivory-billed woodpecker, based on interviews with residents of Brinkley, Arkansas, broadcast on National Public Radio following the public reports of sightings there.[106][107] The Alex Karpovsky film Red Flag features Karpovsky as a filmmaker touring his documentary about the ivory-billed woodpecker, which is also a film he actually made titled Woodpecker.

Arkansas has made license plates featuring a graphic of an ivory-billed woodpecker.[108]

Notes

- The universally accepted starting point of modern taxonomy for animals is set at 1758, with the publishing of Linnaeus' 10th edition of Systema Naturae, although scientists had been coining names in the previous century.[5]

References

- BirdLife International (2018). "Campephilus principalis (amended version of 2016 assessment)". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T22681425A125486020. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- "Ivory-billed Woodpecker Campephilus principalis". Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- "Annual Report of the ABA Checklist Committee: 2007 – Flight Path" (PDF). Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- Catesby, Mark (1731). Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahamas (1st ed.). London: Royal Society House. p. 16.

- Polaszek, Andrew (2010). Systema Naturae 250 - The Linnaean Ark. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. p. 34. ISBN 9781420095029.

- Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae per Regna Tria Naturae, Secundum Classes, Ordines, Genera, Species, cum Characteribus, Differentiis, Synonymis, Locis, Vol. I (in Latin). v.1 (10th revised ed.). Holmiae: (Laurentii Salvii). p. 113.

- Gray, George Robert (1840). A List of the Genera of Birds : with an Indication of the Typical Species of Each Genus. London: R. and J.E. Taylor. p. 54.

- Dennis, John V. (1948). "A last remnant of Ivory-billed Woodpeckers in Cuba". Auk. 65 (4): 497–507. doi:10.2307/4080600. JSTOR 4080600.

- Jackson (2004), page 197

- Robert C. Fleischer; Jeremy J. Kirchman; John P. Dumbacher; Louis Bevier; Carla Dove; Nancy C. Rotzel; Scott V. Edwards; Martjan Lammertink; Kathleen J. Miglia; William S. Moore (2006). "Mid-Pleistocene divergence of Cuban and North American ivory-billed woodpeckers". Biology Letters. 2 (#3): 466–469. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2006.0490. PMC 1686174. PMID 17148432.

- Leonard, Pat; Chu, Miyoko (Autumn 2006). "DNA Fragments Yield Ivory-bill's Deep History". BirdScope. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. 20 (#4). Archived from the original on 5 June 2011.

- Gill, Frank; Donsker, David, eds. (2019). "Woodpeckers". World Bird List Version 9.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- Hoose, Phillip M. (2004). The Race to Save the Lord God Bird. Douglas & McIntyre. ISBN 978-0-374-36173-0.

They gave it names like 'Lord God bird' and 'Good God bird'.

- Steinberg, Michael K. (2008). Stalking the Ghost Bird: The Elusive Ivory-Billed Woodpecker in Louisiana. LSU Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-3305-7.

Nicknamed the 'Lord God Bird', the 'Grail Bird', 'King of the Woodpeckers', and 'Elvis in Feathers', the ivory-bill – thought to be extinct since the 1940s – fascinates people from all walks of life and has done so for centuries.

- Hoose (2004), page 92

- Winkler, Hans; Christie, David A. & Nurney, David (1995). Woodpeckers: An Identification Guide to the Woodpeckers of the World. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-72043-1.

- Jackson (2004), page 46

- Jackson (2004), page 47

- Jackson, Jerome (2002). "Ivory-billed Woodpecker". Birds of North America Online. Retrieved 11 October 2009.

- Hasbrouck, Edwin M. (April 1891). "The Present Status of the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis)". The Auk. 8 (2): 174–186. doi:10.2307/4068072. JSTOR 4068072.

- Cooke, Wells Woodbridge (1888). United States. Bureau of Biological Survey (ed.). "Report on Bird Migration in the Missipi Valley in the Years 1884 and 1885". Bulletin. U.S. Government Printing Office (2): 128.

- Tanner (1942), page 3

- Cox, Edward Travers (1869), First Annual Report of the Geological Survey of Indiana, Made During the Year 1869, Indianapolis: Alexander H. Conner

- Tanner (1942), page 12

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Region 4 (2010). Recovery Plan for the Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus Principalis) (PDF). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Southeast Region.

- Schorger, A. W. (December 1949). "An Early Record and Description of the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker in Kentucky". The Wilson Bulletin. Wilson Ornithological Society. 61 (4): 235. JSTOR 4157806.

- Wetmore, Alexander (March 1943). "Evidence for the Former Occurrence of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker in Ohio". The Wilson Bulletin. 55 (1): 55. JSTOR 4157216.

- Parmalee, Paul W. (June 1967). "Additional Noteworthy Records of Birds from Archaeological Sites". The Wilson Bulletin. Wilson Ornithological Society. 79 (2): 155–162. JSTOR 4159587.

- Jackson (2004), page 264

- Coues, Elliott; Yarrow, H. C. (1878). "Notes on the Natural History of Fort Macon, N. C., and Vicinity". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 30 (4): 21–28. JSTOR 4060358.

- Jefferson, Thomas (1787). "6". Notes on the State of Virginia. John Stockdale. p. 113.

- Audubon (1842), page 214

- Travels into North America: Containing Its Natural History, and a Circumstantial Account of Its Plantations and Agriculture in General; with the Civil, Ecclesiastical and Commercial State of the Country, the Manners of the Inhabitants, and Several Curious and Important Remarks on Various Subjects. 1. Translated by Forster, John Reinhold (2 ed.). London: T. Lowndes. 1772. p. 377.

- Gallagher (2005), page 53

- Jackson (2004), page 24

- Arthur Augustus Allen. "Ivory-billed woodpecker". In Arthur Cleveland Bent (ed.). Life Histories of Familiar North American Birds. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- Jackson (2004), page 25

- Audubon (1837), page 217

- Henry Miller Stevenson, Bruce H. Anderson (1994). The Birdlife of Florida. University Press of Florida. pp. 407–410. ISBN 0813012880.

- Ojeda, Valeria; Chazarretab, Laura (15 September 2014). "Home range and habitat use by Magellanic Woodpeckers in an old-growth forest of Patagonia". Canadian Journal of Forest Research. 44 (10): 1265–1273. doi:10.1139/cjfr-2013-0534.

- Jackson (2004), page 33)

- Jackson (2004), page 34

- Tanner (1942), page 70

- Jackson (2004), page 28

- >Allen, Arthur A.; Kellog, P. Paul (1937). "Recent Observations on the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker". Auk. 54 (#2): 164–184. doi:10.2307/4078548. JSTOR 4078548.

- Jackson (2004), page 29

- Jackson (2004), page 30

- Tanner (1942), page 72

- Jackson (2004), page 31

- Tanner (1942), page 65

- Jackson (2004), page 15

- Jackson (2004), page 41

- United States. Army. Corps of Engineers (1982). Atchafalaya Basin Floodway System: Environmental Impact Statement.

- "Ecology and Behavior". The Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

- "Studying a Vanishing Bird". The Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

- "History of the Ivorybill: The Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis), one of the largest woodpeckers known ... has become elusive to ornithologists as well as birdwatchers". ivorybill.org. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- Tensas River National Wildlife Refuge, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, Ivory-Billed Woodpecker Records (Mss. 4171), Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections, Louisiana State University Libraries, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, USA (accessed 02/18/2015)

- Gallagher (2005), page 16

- Weidensaul, Scott (2005): Ghost of a chance. Smithsonian Magazine. August 2005: pp. 97–102.

- "ABA Checklist". American Birding Association. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- Mendenhall, Matt (2005). "Reported Ivory-bill Sightings Since 1944". Birders World Magazine. Archived from the original on 15 June 2006. Retrieved 8 July 2006.

- Jones, Clark D.; Jeff R. Troy; Lars Y. Pomara (June 2007). "Similarities between Campephilus woodpecker double raps and mechanical sounds produced by duck flocks". The Wilson Journal of Ornithology. 119 (#2): 259–262. doi:10.1676/07-014.1.

- Eastman, Whitney (1958). "Ten year search for the Ivory-billed Woodpecker". Atlantic Naturalist. 13 (4).

- "Ivory-billed Woodpecker Searches, 1948-1971". Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- "1950-52 Chipola River Wildlife Sanctuary subject of research team". Blountstown, Florida: The County Record. 1 June 2017.

- Dennis, John V. (November–December 1967). "The ivory-bill flies still". Audubon: 38–45.

- Hardy, John Williams (June 1977). "A Tape Recording of a Possible Ivory-billed Woodpecker Call". American Birds. 29 (3): 647–651. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- Williams, James (December 2001). "Ivory-billed Dreams, Ivory-billed Reality". Birding. pp. 514–522.

- Collins, George Fred (1970). "The Ivory-billed Woodpecker in Texas". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)Texas A&M University - Moser, Don (7 April 1972). "THE LAST A search for the rarest creature on earth". Time. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- United States Congress (1969). Congressional Record: Proceedings and Debates of the ... Congress, Volume 115, Part 30. U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 40392–40393.

- United States. Congress. Senate. Interior and Insular Affairs (1971). Hearing before the Subcommittee on Parks and Recreation of the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs United States Senate Ninety-First Congress Second Session on S. 4 To Establish The Big Thicket National Park in Texas. Washington, DC.

- Agey, H. Norton; Heinzmann, George M. (April 1971). "The Ivory-billed Woodpecker found in central Florida". The Florida Naturalist.

- Morris, Tim (9 January 2006). "the grail bird". lection. Retrieved 8 July 2006.

- Sykes, Paul W. Jr. (2016). "A Personal Perspective on Searching for the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker: A 41-Year Quest". USGS Staff -- Published Research: 1026.

- Brett Martel (19 November 2000). "Reported Sighting of 'Extinct' Woodpecker Drives Bird-Watchers Batty". Los Angeles Times.

- Jerome A. Jackson (1 June 2002). "Jerry Jackson assesses David Kulivan's report of Ivory-billed Woodpeckers in the Pearl River Swamp, Louisiana". Bird Watching Daily. Retrieved 14 October 2019. Cite magazine requires

|magazine=(help) - Fitzpatrick, John W. (Summer 2002). "Ivory-bill Absent from Sounds of the Bayous". Birdscope. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Archived from the original on 12 July 2006. Retrieved 8 July 2006.

- Fitzpatrick, J. W.; Lammertink, M; Luneau Jr, M. D.; Gallagher, T. W.; Harrison, B. R.; Sparling, G. M.; Rosenberg, K. V.; Rohrbaugh, R. W.; Swarthout, E. C.; Wrege, P. H.; Swarthout, S. B.; Dantzker, M. S.; Charif, R. A.; Barksdale, T. R.; Remsen Jr, J. V.; Simon, S. D.; Zollner, D (2005). "Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) Persists in Continental North America" (PDF). Science. 308 (#5, 727): 1460–2. Bibcode:2005Sci...308.1460F. doi:10.1126/science.1114103. PMID 15860589.

- Pranty, Bill (November 2011). "22nd Report of the ABA Checklist Committee" (PDF). Birding. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- Dalton, Rex (10 February 2010). "Still looking for that woodpecker". Nature. Nature Publishing Group. 463 (7282): 718–719. doi:10.1038/463718a. PMID 20148004. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- Sibley, D. A. (2006). "Comment on "Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) Persists in Continental North America"" (PDF). Science. 311 (#5, 767): 1555a. doi:10.1126/science.1122778. PMID 16543443. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 May 2015. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- Collinson, J Martin (March 2007). "Video analysis of the escape flight of Pileated Woodpecker Dryocopus pileatus: does the Ivory-billed Woodpecker Campephilus principalis persist in continental North America?". BMC Biology. 5: 8. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-5-8. PMC 1838407. PMID 17362504.

- Fitzpatrick, J. W.; Lammertink, M; Luneau Jr, M. D.; Gallagher, T. W.; Rosenberg, K. V. (2006). "Response to Comment on "Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) Persists in Continental North America". Science. 311 (5767): 1555b. doi:10.1126/science.1123581.

- Hill, Geoffrey E.; Mennill, Daniel J.; Rolek, Brian W.; Hicks, Tyler L. & Swiston, Kyle A. (2006). "Evidence Suggesting that Ivory-billed Woodpeckers (Campephilus principalis) Exist in Florida" (PDF). Avian Conservation and Ecology. 1 (3): 2. doi:10.5751/ace-00078-010302. Retrieved 13 October 2019. Erratum

- Hill, Geoff (2 August 2009). "Updates from Florida". Auburn University. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 7 August 2009.

- Florida Ornithological Society Records Committee (7 March 2007). "FOS Board Report — April 2007". Florida Ornithological Society. Retrieved 27 January 2010.

- Collins, Michael D. (2011). "Putative audio recordings of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis)" (PDF). Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 129 (3): 1626–1630. Bibcode:2011ASAJ..129.1626C. doi:10.1121/1.3544370. PMID 21428525. supplemental material

- Collins, Michael D. (2017). "Video evidence and other information relevant to the conservation of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis)". Heliyon. 3 (1): e00230. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2017.e00230. PMC 5282651. PMID 28194452.

- Collins, Michael D. (2017). "Periodic and transient motions of large woodpeckers". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 12551. Bibcode:2017NatSR...712551C. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-13035-6. PMC 5624965. PMID 28970530.

- Collins, Michael D. (2018). "Using a drone to search for the Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis)". Drones. 2 (1): 11. doi:10.3390/drones2010011.

- Collins, Michael D. (2019). "Statistics, probability, and a failed conservation policy". Statistics and Public Policy. 6 (1): 67–79. doi:10.1080/2330443X.2019.1637802.

- Michelle Donahue (25 January 2017). "Possible Ivory-Billed Woodpecker Footage Breathes Life Into Extinction Debate". Audubon Society.

- Leese, Benjamin E. (Fall 2006). "Scarlet scalps and ivory bills: Native American uses of the ivory-billed woodpecker". The Passenger Pigeon. 68 (3): 213–226. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- O'Shea, John M.; Schrimper, George D.; Ludwickson, John K. (August 1982). "Ivory-billed woodpeckers at the big village of the Omaha". Plains Anthropologist. 27 (97): 245–248. doi:10.1080/2052546.1982.11909067. JSTOR 25668290.

- Tanner (1942), page 55

- Hoose (2004), page 24

- Parmalee, Paul W. (April 1958). "Remains of Birds from Illinois Indian Sites". The Auk. 75: 169–176. doi:10.2307/4081887. JSTOR 4081887.

- Hill, Geoffrey E. (2008). "An Alternative Hypothesis for the Cause of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker's Decline". The Condor. 110 (4): 808–810. doi:10.1525/cond.2008.8658.

- Capainolo, Peter; Kenney, Shannon P.; Sweet, Paul R. (2007). "Extended-wing preparation made from a 117- year-old Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) specimen". The Auk. 124 (2): 705–709. doi:10.1642/0004-8038(2007)124[705:EPMFAY]2.0.CO;2.

- White, Mel (December 2006). "The Ghost Bird". National Geographic. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- Steinberg (2008), page 48

- Peterson, Roger (2006). Bill Thompson (III) (ed.). All Things Reconsidered: My Birding Adventures. Houghton Mifflin. pp. 115–124. ISBN 0618758623.

- Sam Crowe (March 2006). "Call of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker Celebration". Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- Saikku, Mikko (April 2010). "Reviewed Work(s): STALKING THE GHOST BIRD: The Elusive Ivory-Billed Woodpecker in Louisiana by Michael K. Steinberg; THE TRAVAILS OF TWO WOODPECKERS: Ivory-Bills &Imperials by Noel F. R. Snyder, David E. Brown and Kevin B. Clark". Geographical Review. American Geographical Society. 100 (2): 274–278. JSTOR 27809322.

- "Brinkley, Ark., Embraces 'The Lord God Bird'". All Things Considered. National Public Radio. 6 July 2005. Retrieved 9 July 2006.

- "Sufjan Stevens – "The Lord God Bird" (MP3)". Npr.org. 27 April 2005. Archived from the original on 1 October 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- "Game & Fish Ivory Billed Woodpecker Plate". Arkansas Department of Finance and Administration. Arkansas Department of Finance and Administration. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

Further reading

- Audubon, John James LaForest (1835–38): The Ivory-billed Woodpecker. In: Birds of America 4. ISBN 0-8109-2061-1 (H. N. Abrams 1979 edition — the book itself is in the public domain)

- Farrand, John & Bull, John, The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Birds: Eastern Region, National Audubon Society (1977)

- Gallagher, Tim W. (2005): The Grail Bird: Hot on the Trail of the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker Houghton Mifflin, Boston. ISBN 0-618-45693-7

- Hoose, Phillip M. (2004) The Race to Save the Lord God Bird, Douglas & McIntyre. New York. ISBN 978-0-374-36173-0

- Jackson, Jerome A. (2004): In Search of the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker. Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 1-58834-132-1

- Tanner, James T. (1942). The Ivory-Billed Woodpecker. National Audubon Society, N.Y.

- Winkler, H.; Christie, D. A. & Nurney, D. (1995): Woodpeckers: A Guide to the Woodpeckers of the World. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston. ISBN 0-395-72043-5

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Campephilus principalis. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Campephilus principalis |

- The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service draft recovery plan

- The Search for the Ivory-billed Woodpecker. Cornell Lab of Ornithology website with video and sound files. Retrieved 2006-OCT-6.