Itavia Flight 870

On 27 June 1980, Itavia Flight 870 (IH 870, AJ 421), a McDonnell Douglas DC-9 passenger jet en route from Bologna to Palermo, Italy, crashed into the Tyrrhenian Sea between the islands of Ponza and Ustica, killing all 81 people on board. Known in Italy as the Ustica massacre ("strage di Ustica"), the disaster led to numerous investigations, legal actions and accusations, and continues to be a source of controversy, including claims of conspiracy by the Italian government and others. The Prime Minister of Italy at the time, Francesco Cossiga, attributed the crash to being accidentally shot down during a dogfight between Libyan and NATO fighter jets. A 1994 report argued the cause of the crash was a terrorist bomb, one in a years-long series of bombings in Italy. On 23 January 2013, Italy's top criminal court ruled that there was "abundantly" clear evidence that the flight was brought down by a missile, but the perpetrators are still missing.[1]

I-TIGI, the aircraft involved in the accident, 1973. | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | 27 June 1980 |

| Summary | Disputed:

|

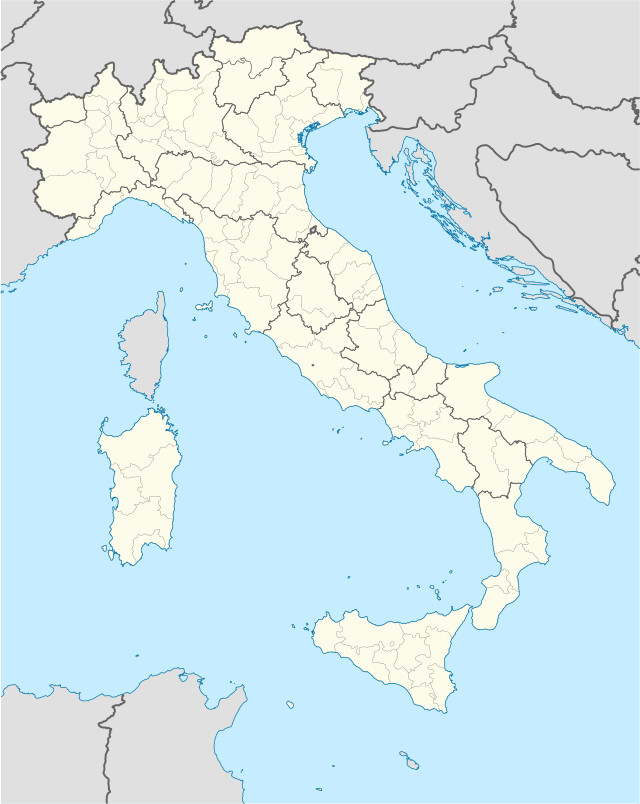

| Site | Tyrrhenian Sea near Ustica, Italy |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | McDonnell Douglas DC-9-15 |

| Operator | Itavia |

| Registration | I-TIGI |

| Flight origin | Guglielmo Marconi Airport (BLQ) |

| Destination | Palermo International Airport (PMO) |

| Passengers | 77 |

| Crew | 4 |

| Fatalities | 81 |

| Survivors | 0 |

Aircraft

The aircraft, a McDonnell Douglas DC-9-15 flown as Aerolinee Itavia Flight 870, was manufactured in 1966 and acquired by the airline on 27 February 1972 with the serial number CN45724/22 and registration I-TIGI (formerly N902H,[2] operated by Hawaiian Airlines).

Flight history

On 27 June 1980 at 20:08 CEST, the plane departed with a delay of one hour and 53 minutes from Bologna Guglielmo Marconi Airport for a scheduled service to Palermo Punta Raisi Airport, Sicily. With 77 passengers aboard, Captain Domenico Gatti and First Officer Enzo Fontana were at the controls, with two flight attendants.[3] The flight was designated IH 870 by air traffic control, while the military radar system used AJ 421.[4]

Contact was lost shortly after the last message from the aircraft was received at 20:37, giving its position over the Tyrrhenian Sea near the island of Ustica, about 120 kilometres (70 mi) southwest of Naples.[5] At 20:59 CEST, the aircraft broke-apart in mid-air and crashed.[6] Two Italian Air Force F-104s were scrambled at 21:00 from Grosseto Air Force Base to locate the accident area and search for any survivors, but failed to do so because of poor visibility.

Floating wreckage and bodies were later found in the area. There were no survivors among the 81 people on board.

Official investigation

After years of investigation, no official explanation or final report has been provided by the Italian government. In 1989, the Parliamentary Commission on Terrorism, headed by Senator Giovanni Pellegrino, issued an official statement concerning the disappearance of Flight 870, which became known as the "Ustica Massacre" (Strage di Ustica).

The investigatory phase of the case has suggested that: "the action is primarily an act of war, a de facto unreported war – as is usual from Pearl Harbor onwards, until the last Balkan conflict – an international police operation, in fact, accruing to the great powers, since there was no mandate in this sense; a non-military coercive action exercised lawfully or illicitly, from one State against another; or act of terrorism, as it was later wished, of an attack on a head of state or regime leader."{Ordinanza-sentenza, 1999, p. 4965}

The perpetrators of the crime remain unidentified. The court, unable to proceed further, declared the case archived.

In July 2006, the re-assembled fragments of the DC-9 were returned to Bologna from Pratica di Mare Air Force Base near Rome.

In June 2008, Rome prosecutors reopened the investigation into the crash after former Italian President Francesco Cossiga (who was prime minister when the incident occurred) said that the aircraft had been shot down by French warplanes.[7] On 7 July 2008, a claim for damages was served to the French President.

High treason charges against Italian Air Force officials

The role of Italian Air Force personnel in the tragedy is unclear. Several Air Force officials have been investigated and brought to court for a number of alleged offences, including falsification of documents, perjury, abuse of office and aiding and abetting. Four generals were charged with high treason, on the allegations that they obstructed government investigation of the accident by withholding information about air traffic at the time of Ustica disaster.

The first ruling, on 30 April 2004, pronounced two of the generals, Corrado Melillo and Zeno Tascio, not guilty of high treason. Lesser charges against a number of other military personnel were also dropped. Other allegations could not be pursued further after the expiration of the statute of limitations, as the disaster had occurred more than 15 years prior. For this same reason, action could not be taken against the other two generals, Lamberto Bartolucci and Franco Ferri. However, the ruling did not acquit them, and they were still alleged to be guilty of treason. In 2005, an appeals court ruled that the accusations were made on a complete absence of evidence. On 10 January 2007, the Italian Court of Cassation upheld this ruling and conclusively closed the case, fully acquitting Bartolucci and Ferri of any wrongdoing.

In June 2010, Italian President Giorgio Napolitano urged all Italian authorities to cooperate in the investigation of the incident.[8]

In September 2011, a Palermo civil tribunal ordered the Italian government to pay 100 million euros ($137 million) in civil damages to the relatives of the victims for failing to protect the flight, concealing the truth and destroying evidence.[9]

On 23 January 2013, the Civil Cassation Court ruled that there was "abundantly" clear evidence that the flight was brought down by a stray missile, confirming the lower court's order that the Italian government must pay compensation.[1]

In April 2015, an appeals court in Palermo confirmed the rulings of the 2011 Palermo civil tribunal and rejected an appeal by the state attorney.[10]

Hypotheses on the causes

Speculation at the time and in the years since has been fueled in part by media reports, military officials' statements and ATC/CVR recordings. Adding to the widespread conjecture was the observation of radar images showing trails of objects moving at high speeds.

Terrorist bomb

After the series of bombings that hit Italy in the 1970s, a terrorist act was the first explanation to be proposed. As the flight was delayed in Bologna by almost three hours, a bomb's timer may have been set to actually cause an explosion at the Palermo airport, or on a further flight of the same plane. The technical commission supporting a 1990 judicial enquiry reported that an explosion in the rear toilet, and not a missile strike, was the only conclusion supported by the wreckage analysis.[11]

Fourteen years after the accident, a 1994 joint investigation was carried out by the British Air Accidents Investigation Branch (AAIB) and Italian investigators; this team included veteran British Air Accident Investigator A. Frank Taylor and Engineer Goran Lilja of Sweden. The team was surprised that anyone came to any conclusion with so little of the aircraft recovered and asked the Italian government to fund another salvage operation to recover more of the aircraft from the floor of the Mediterranean Sea. While investigating the 21 December 1988 bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland, A.Frank Taylor helped create a software program that could locate widely scattered debris. This software program had two effects, 1) how far a piece will travel in the direction that the aircraft was originally traveling, and 2) how far the piece will be blown downwind. An additional 40% of the aircraft wreckage was located within a few meters of where the software program predicted it would be found. The location of the wreckage on the sea floor demonstrated which pieces came off the aircraft first.[3]

The investigation found conclusive physical evidence (as per the wreckage recovered) that a bomb had indeed exploded mid-flight in the rear lavatory. A large section of the aircraft's fuselage around the lavatory was never recovered (presumably having disintegrated in the explosion). A test explosion in a DC-9 lavatory showed the resulting deformation in the surrounding structure to be almost identical to that of the incident aircraft.

From “A Case History Involving Wreckage Analysis: Lessons from the Ustica investigations”

4 Investigation Findings

4.1 It was concluded that the accident was brought about by in-flight break- up resulting from extensive structural damage caused by the detonation of an explosive charge in the rear (starboard) toilet.

4.2 The charge was probably located in the outer wall of the toilet although other nearby positions cannot be ruled out.

4.3 For the preferred position the charge would most probably have been inserted via the tissue holder just forward of station 801 and pushed rearwards to lie to the rear of the frame at station 801 and at a height at or just above the lower skin of the adjacent engine pylon.

4.4 Other less likely but possible and accessible positions include either inside the toilet waste tank, via the waste hole, or on top of it, via the cupboard under the wash basin.[12]

However, the Italian high courts dismissed this final report as insignificant to their own investigation, and the report was never considered.

Missile strike during military operation

Major sources in the Italian media have alleged that the aircraft was shot down during a dogfight involving Libyan, United States, French and Italian Air Force fighters in an assassination attempt by NATO members on an important Libyan politician, perhaps even Libyan leader Muammar al-Gaddafi, who was flying in the same airspace that evening.[13] This version was supported in 1999 by investigative magistrate Rosario Priore,[14] who said in his concluding report that his investigation had been deliberately obstructed by the Italian military and members of the secret service, in compliance with NATO requests.[14]

According to the Italian media, documents from the archives of the Libyan secret service passed on to Human Rights Watch after the fall of Tripoli show that Flight 870 and a Libyan MiG were attacked by two French jets.[15]

On 18 July 1980, 21 days after the Aerolinee Itavia Flight 870 incident, the wreckage of a Libyan MiG-23, along with its dead pilot, was found in the Sila Mountains in Castelsilano, Calabria, southern Italy, according to official reports.[16]

Conspiracy theories

Several conspiracy theories explaining the disaster persist.[17] For example, the vessel that carried out the search for debris on the ocean floor was French, but only US officials had access to the aircraft parts they found. Several radar reports were erased and several Italian generals were indicted 20 years later for obstruction of justice. The difficulty the investigators and the victims' relatives had in receiving complete, reliable information on the Ustica disaster has been popularly described as un muro di gomma (literally, a rubber wall),[18] because investigations just seemed to "bounce back".

Memorial

On 27 June 2007, the Museum for the Memory of Ustica was opened in Bologna. The museum is in possession of parts of the plane, which are assembled and on display, including almost all of the external fuselage. The museum also has objects belonging to those on board that were found in the sea near the plane. Christian Boltanski was commissioned to produce a site-specific installation. The installation consists of:

- 81 pulsing lamps hanging over the plane

- 81 black mirrors

- 81 loudspeakers (behind the mirrors)

Each loudspeaker describes a simple thought/worry (e.g. "when I arrive I will go to the sea") All the objects found are contained in a wooden box covered with a black plastic skin. A small book with the photos of all objects and various information is available to visitors upon request.

Dramatization

The accident was featured in the 13th season of the Canadian documentary series Mayday in an episode entitled "Massacre over the Mediterranean". The film examined the heavy public pressure placed upon investigators to uncover the cause of the accident, and also considered the three separate technical investigations that occurred. It ultimately advanced the conclusions of the third and final technical investigation, which concluded that the wreckage ruled out a missile and pointed to an explosion in or near the rear lavatory.[11]

The documentary was highly critical of the Italian judiciary's failure to officially release the third technical investigation to the public, or to consider its conclusion that missiles were not responsible. Interviewee David Learmount of Flight International magazine made the following comments:

The judiciary in Italy just found Frank Taylor's findings inconvenient. I don't think they ordered it not to be published, they just made a decision that they wouldn't publish it.[3]

I'm sorry, but Italy is a dreadful place to have an aviation accident. If you want the truth, you're less likely to find it there than just about anywhere else in the world.[3]

Frank Taylor's team didn't reach any conclusions except ones which were based on hard physical evidence. There was no theorizing going on.[3]

Frank Taylor, a British investigator involved in the third technical inquest, also commented:

We discovered quite clearly that somebody had planted a bomb there, but nobody on the legal side, it would appear, believed us and therefore, so far as we are aware, there has been no proper search for who did it, why they did it, or anything else. As an engineer and an investigator I cannot see why anybody would want to consider anything other than the truth.[3]

A 1991 Italian film by Marco Risi, The Rubber Wall, tells the story of a journalist in search of answers to the many questions left open by the accident. The film theorises on a few possible scenarios, including the possibility that the DC-9 was mistakenly shot down during an aerial engagement between NATO and Libyan jet fighters.

See also

References

- "Italian court: Missile caused 1980 Mediterranean plane crash; Italy must pay compensation". The Washington Post. Associated Press. 23 January 2013.

- "I-TIGI Itavia McDonnell Douglas DC-9-15 – cn 45724 / ln 22". planespotters.net. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- "Massacre over the Mediterranean" Mayday [documentary TV series].

- Ranter, Harro. "ASN Aircraft accident Douglas DC-9-15 I-TIGI Ustica, Italy [Tyrrhenian Sea]". aviation-safety.net. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- "Italian DC-9 lost off Sicily." Flight International. 5 July 1990. p. 2. (Direct PDF link, Archive)

- "DAGLI USA E' ARRIVATO IL NASTRO DEL DC9 – la Repubblica.it" [THE TAPE OF DC 9 HAS COME FROM THE USA]. Archivio – la Repubblica.it (in Italian). Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- Italy Reopens Probe Into 1980 Plane Crash: Media, Reuters, 22 June 2008

- Troendle, Stefan (27 June 2010). "Napolitano fordert Aufklärung des Absturzes von Ustica". Tagesschau. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

Zum Jahrestag der Flugzeugkatastrophe von Ustica hat Italiens Staatspräsident Giorgio Napolitano alle staatlichen Stellen aufgefordert, daran mitzuarbeiten, das Unglück endlich aufzuklären. Es müsse eine befriedigende und ehrliche Rekonstruktion der Ereignisse stattfinden, damit alle Unklarheiten beseitigt würden.

- "Italy court fines government $137 million over mysterious crash of plane over Ustica". The Washington Post. Associated Press. 13 September 2011.

- "Ustica, Corte d'Appello conferma: "Il Dc-9 venne abbattuto da un missile"". Il Fatto Quotidiano. 8 April 2015.

- A. Frank Taylor, "A Case History Involving Wreckage Analysis: Lessons from the Ustica investigations" (Archive)

- See:

- A. Frank Taylor (March 1995) "Accident to Itavia DC-9 near Ustica, 27 June 1980: wreckage and impact information & analysis," International Society of Air Safety Investigators Forum (Paris, October 1994), 28 (1) : 6 ff. Available on-line at: Strage di Ustica

- A. F. Taylor (1998) "The study of aircraft wreckage: the key to accident investigation," Technology, Law and Insurance, 3 (2) : 129–147.

- A. Frank Taylor, "A Case History Involving Wreckage Analysis: Lessons from the Ustica investigations" (Cranfield, Bedfordshire, England, UK: Cranfield University, 1998, revised: 2006). Available on-line at: Aviation-Safety.net Archived 21 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Thomas Van Hare (27 June 2012). "Italy's Darkest Night". Historic Wings.

- The Mystery of Flight 870, The Guardian, 21 July 2006

- Noel Grima (18 September 2011). "Libyan secret documents said to uncover Ustica tragedy… and how Gaddafi escaped to Malta unscathed". The Malta Independent.

- Cooper, T.; Grandolini, A. (2015). Libyan Air Wars: Part 1: 1973–1985. Africa@War (in Malay). Helion, Limited. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-910777-51-0. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Elisabetta Povoledo (10 February 2013). "Conspiracy Buffs Gain in Court Ruling on Crash". The New York Times.

- ALAN COWELL (10 February 1992). "Italian Obsession: Was Airliner Shot Down?". The New York Times.

External links

- Official Site of the Association of the Relatives of the Victims of the Accident (dead link)

- AirDisaster.Com Accident Synopsis of Flight 870

- Accident details at planecrashinfo.com

- Il Muro di gomma on IMDb, film about the accident

- The mystery of flight 870 – Guardian Newspaper.

- https://www.webcitation.org/6SAEPRdmq?url=http://aviation-safety.net/pubs/other/Taylor_paper_Ustica_illustrated.pdf