Italian nuclear weapons program

The Italian nuclear weapons program was an effort by Italy to develop nuclear weapons in the late 1960s and early 1970s. After abortive proposals to establish a multilateral program with NATO Allies in the 1950s and 1960s, Italy launched a national nuclear weapons program, including testing a ballistic missile. The program ended in 1975 upon Italy's accession to the Non-Proliferation Treaty.[1] Currently, Italy does not produce or possess nuclear weapons but takes part in the NATO nuclear sharing program.[2]

| Weapons of mass destruction |

|---|

|

| By type |

| By country |

|

| Proliferation |

| Treaties |

|

Background

At the end of World War II, Italy was quick to realise the geopolitical situation and created a political strategy that relied on multilateralism, principally through a close relationship with the United States, membership of NATO and greater European integration.[3] The Italian Army was particularly keen to acquire nuclear weapons, seeing them primarily in a tactical role.[4]

Italy started hosting US nuclear weapons under NATO's nuclear sharing policy. The first nuclear weapons deployed were MGR-1 Honest John and MGM-5 Corporal rockets in 1957,[5] and were later followed by the MIM-14 Nike Hercules surface-to-air missile. However, all these systems were under sole US control and so Italy simultaneously pursued dialogue with other European nations on a collaborative nuclear programme.[3] Discussions were held with France and Germany about a joint nuclear deterrent, but these were curtailed in 1958 by Charles de Gaulle's desire for an independent French deterrent.[6]

The decision by Switzerland on 23 December 1958 to pursue a nuclear weapons programme put an additional impetus on Italy.[7] Pressure was made on the United States to provide additional nuclear weapons. On 26 March 1959, agreement was made that the Italian Air Force would receive 30 PGM-19 Jupiter ballistic missiles to operate from Gioia del Colle Air Base.[4] The first missiles arrived on 1 April 1960.[8] This time the Americans provided a dual-key system that led the Italian government to believe they had greater control over the deterrent and thus more power in NATO.[3] Explicitly, the new missiles could be used "for the execution of NATO plans and policies in times of peace as well as war".[4] The missiles were operated by a new brigade, the 36ª Aerobrigata.[8]

Multilateral Force

At the same time as working with the United States, Italy explored working within the NATO Multilateral Force (MLF) concept to develop a European nuclear force. MLF was a concept promoted by the United States to place all NATO nuclear weapons not operated by their own services under a joint control, with dual-key control by American and European forces. For the United States, the MLF was an attempt to balance the desire from other members to play a role in nuclear deterrence with their interest in bringing all existing and potential Western nuclear arsenals under the umbrella of a more cohesive NATO alliance.[9] Italy had long argued for nuclear cooperation, with Minister of Defence Paolo Emilio Taviani saying on 29 November 1956 that the Italian government was trying to persuade their "Allies to remove the unjustified restrictions regarding the access of NATO countries to new weapons."[4] The policy was pursued by the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, and formed a fundamental part of the negotiations around the Nassau Agreement between the United States and the United Kingdom and the attempted accession of the United Kingdom to the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1961.[10]

Under MLF, the United States proposed that various NATO countries operate UGM-27 Polaris IRBM on seaborne platforms, principally nuclear submarines. The Italian Navy took the cruiser Giuseppe Garibaldi out of service and rebuilt the ship between 1957 and 1961 as a guided missile cruiser with launchers for four Polaris missiles.[6] Shortly afterwards, in December 1962, Italian Minister of Defence Giulio Andreotti officially asked the United States for assistance in developing nuclear propulsion for its fleet.[3]

The Italian government saw the growth of the movement to halt the proliferation of nuclear weapons as a major challenge to its nuclear programme.[6] At the Eighteen Nation Committee on Disarmament, the Italian government argued that multilateral activity like the MLF as excluded from any agreement on non-proliferation, but found that the Soviet Union required that MLF be terminated as part of their negotiations on the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons and the United States all but killed the agreement on 17 December 1964 with National Security Action Memorandum No. 322.[9] At the same time, on 5 January 1963, the United States announced that they would withdraw the Jupiter missiles as a consequence of the Cuban Missile Crisis.[11] The decision was approved by the Italian government and the missile brigade was deactivated on 1 April 1963.[12]

Italy's indigenous program

With the failure of its multilateral efforts, Italy looked again at creating an independent deterrent. Italy had experience with nuclear technology, with a well developed nuclear power industry with BWR, Magnox, and PWR technologies, as well as the 5MW RTS-1 'Galileo Galilei' test reactor at CAMEN (Italian: Centro Applicazioni Militari Energia Nucleare, Center for Military Applications of Nuclear Energy).[13] It also had a large number of nuclear capable aircraft, including the Lockheed F-104 Starfighter, and was developing the Panavia Tornado with nuclear strike in mind.[14]

Ever since 27 March 1960, when Admiral Pecori Geraldi had argued that a seaborne nuclear force was the most resistant to attack, the navy had looked for an opportunity to take on a nuclear role and had gained experience through the successful test of Polaris missiles from Giuseppe Garibaldi in September 1962.[4]

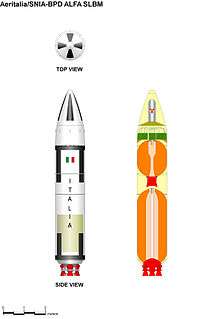

Alfa

In 1971, the Italian Navy began an ingenious program to develop ballistic missiles called Alfa. Officially the project was termed as a development effort for a study on efficient solid-propellant rockets for civil and military applications. It was planned as a two-stage rocket and could be carried on submarines or ships. Test launches with an upper stage mockup took place between 1973 and 1975, from Salto di Quirra. The Alfa was 6.5 metres (21 ft) long and had a diameter of 1.37 metres (4 ft 6 in). The first stage of the Alfa was 3.85 metres (12.6 ft) long and contained 6 t of solid rocket fuel. It supplied a thrust of 232 kN for a duration of 57 seconds. It could carry a one ton warhead for a range of 1,600 kilometres (990 mi), placing European Russia and Moscow in range from the Adriatic Sea.[7]

The combination of high costs of over 6 billion lira and a changing political climate meant that the project was doomed.[15] In addition, there was an increasing risk of nuclear escalation outside Europe and domestic pressure for Italy to take play its part in reducing the nuclear tension. These combined with pressure from the United States led to Italy abandoning its nuclear weapons program and ratifying the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons on 2 May 1975.[6]

The technological heritage of Alfa is today in light solid-propellant space launchers, like the current Vega rocket.[7] The country in more recent years, under the auspices of European space agency has demonstrated the reentry and landing of return of a capsule called IXV.

Potential nuclear targets

The development of the program had been spurred on by similar programs in neighbouring countries, particularly Romania, Switzerland and Yugoslavia.[7] However, in 2005, the former Italian President Francesco Cossiga stated that Italy's plans of retaliation during the Cold War consisted in dropping nuclear weapons on Prague and Budapest if there had been a Soviet first strike against NATO members.[16]

Nuclear weapons in Italy since 1975

Italy has continued to host nuclear weapons on its soil after its own program had halted. Since 1975, the country has been used by the United States Army for their deployment of the BGM-109G Ground Launched Cruise Missile, MGM-52 Lance tactical ballistic missile and W33, W48 and W79 artillery shells.[17] The Italian Army unit 3rd Missile Brigade "Aquileia" was trained to use the munitions until the United States Army removed their last nuclear weapons from Italy in 1992 when they withdrew the last Lance missile.[14]

Current situation

.jpg)

The country is part of the NATO nuclear sharing program and under this program United States maintains absolute custody and control over the nuclear weapons.[2] Given this policy it is unclear whether the Italian Air Force could use these weapons in time of war but some sources claim otherwise.[6] The B61 nuclear bombs mod 3, mod 4 and mod 7[19][20] are stored in two locations, 50 at the Aviano Air Base, and 20-40 at the Ghedi Air Base in 2015.[21][22] They can be delivered by USAF General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcons of 31st Fighter Wing that are based at Aviano and Italian Panavia Tornados of 6º Stormo Alfredo Fusco that are based at Ghedi.[21][23] The Tornado fleet will potentially be replaced by Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning.[24]

See also

References

- R. Craig Nation, "Intra-Alliance Politics: Italian-American Relations 1946-2010" in Italy's Foreign Policy in the Twenty-first Century: The New Assertiveness of an Aspiring Middle Power (eds. Giampiero Giacomello & Bertjan Verbeek), page 38.

- "NATO nuclear policy".

- Nuti, Leopoldo (2017). "A turning point in postwar foreign policy:Italy and the NPT negotiations 1967-1968". In Roland Popp; Liviu Horovitz; Andreas Wenger (eds.). Negotiating the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty: Origins of the Nuclear Order. New York: Routledge. pp. 77–96.

- Nuti, Leopoldo (1992). "Italy and the Nuclear Choices of the Atlantic Alliance, 1955–63". In Beatrice Heuser; Brian Thomas (eds.). Securing Peace in Europe, 1945–62: Thoughts for the post-Cold War Era. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 222–245.

- Fadorini, Paolo (2013). Tactical Nuclear Weapons and Euro-Atlantic Security: The Future of NATO. London: Routledge. p. 62.

- Evangelista, Matthew (2011). "Atomic Ambivalence: Italy's Evolving Attitude to Nuclear Weapons". In Giampiero Giacomello; Bertjan Verbeek (eds.). Italy's foreign policy in the twenty-first century : the new assertiveness of an aspiring middle power. Lanham: Lexington Books. pp. 115–134.

- Wade, Mark (2017). "Alfa". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- Mariani, Antonio (2012). La 36ª Aerobrigata Interdizione Strategica: il contributo Italiano alla guerra fredda (in Italian). Rome: Aeronautica Militare, Ufficio Storico.

- Priest, Andrew (2011). "The President, the 'Theologians' and the Europeans: The Johnson Administration and NATO Nuclear Sharing". The International History Review. 33 (2): 257–275.

- Widén, J.J.; Colman, Jonathan (2007). "Lyndon B. Johnson, Alec Douglas-Home, Europe and the NATO Multilateral Force, 1963-64". Journal of Transatlantic Studies. 5 (2): 179–198.

- De Maria, Michelangelo; Orlando, Lucia (2008). Italy in Space : In Search of a Strategy 1957-1975. Paris: Beauchesne. p. 253.

- Gianvanni, Paolo (2000). "Un ricordo della guerra fredda". JP4 Mensile di Aeronautica (in Italian). 1: 30–35.

- International Atomic Energy Agency (1971). Power and Research Reactors in Member States. Vienna: International Atomic Energy Agency. p. 43.

- Meleca, Vincenzo (2015). Il potere nucleare delle Forze Armate Italiane, 1954-1992 (in Italian). Milan: Greco & Greco editori.

- Castro, Luciano (1982). "Dossier Alfa". Aerospazio: 20–24.

- Interview to Cossiga on Blu notte - Misteri italiani, episode "OSS, CIA, GLADIO, i Rapporti Segreti tra America e Italia" of 2005

- Duke, Simon (1989). United States Military Forces and Installations in Europe. Stockholm: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. p. 88.

- Maurizi, Stefania (20 July 2017). "Gli Usa mettono il segreto sulle armi atomiche in Italia". la Repubblica (in Italian). Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- Iacch, Franco (30 August 2017). "Gli Usa testano la nuova bomba nucleare che giungerà in Italia". il Giornale (in Italian). Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- "In Italia 90 bombe atomiche Usa". La Stampa (in Italian). 15 September 2007. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- Kristensen, Hans M.; Norris, Robert S. (2015). "US nuclear forces, 2015". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. pp. 107–119. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - Tirinnanzi, Luciano (23 April 2013). "Armi nucleari in Italia: dove, come, perché: Il Pentagono sta per investire 11 miliardi di dollari per ammodernare gli ordigni nucleari presenti in Europa e in Italia". panorama.it (in Italian). Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- Robertson, Patsy (22 September 2008). "Factsheet 31 Fighter Wing (USAFE)". Air Force Historical Research Agency. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- Kierulf, John (2017). Disarmament under International Law. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 64.