Intellectual courage

Intellectual courage falls under the family of philosophical intellectual virtues, which stems from an individual's own doxastic logic.[1]

Broadly differentiated from physical courage,[1] intellectual courage refers to the cognitive risks strongly tied with an individual's personality traits and willpower, so as to say an individual's quality of mind.[2][3] Branches include (but not exclusive to): Intellectual humility, Intellectual responsibility, Intellectual honesty, Intellectual perseverance, Intellectual empathy, Intellectual integrity and Intellectual fair-mindedness.[4]

Existing under numerous different definitions, intellectual courage is prevalent in everyone,[1] and is often dependent on the context and/or situation it falls under.[5] As such, famous classical philosophers such as Socrates, Plato and Aristotle, have studied and observed the importance of this virtue to a great extent, so as to understand and grasp the impacts of intellectual courage on the human mind.[6][7]

Over the years and generations of observation and debate, intellectual courage has developed different interpretations, largely influenced by the writings of philosophers, changes in culture and shifts in societal norms.[5]

The opposite of achieving intellectual courage is referred to as intellectual arrogance.[8]

Definitions

It is believed that intellectual courage itself, by nature does not often undergo any changes.[9] In fact, it is the understanding by those who study and learn of it, together with the influence of ever-changing cultures, that defines the gaps between the different interpretations.[9]

Although very much related to its parent term, courage, intellectual courage ventures in deeper towards ensuring that an action any person may take, is aligned with the unwavering rational beliefs that that said person holds.[2] On a daily basis, many emotions such as fear and desire easily influence decisions.[10] The degree to which a person is able to control or give in to such emotions, determines the strength of one's intellectual courage.[2]

A concise interpretation of intellectual courage is as quoted below,

Intellectual courage may be defined as having a consciousness of the need to face and fairly address ideas, beliefs or viewpoints toward which one has strong negative emotions and to which one has not given a serious hearing. Intellectual courage is connected to the recognition that ideas that society considers dangerous or absurd are sometimes rationally justified (in whole or in part). Conclusions and beliefs inculcated in people are sometimes false or misleading. To determine for oneself what makes sense, one must not passively and uncritically accept what one has learned. Intellectual courage comes into play here because there is some truth in some ideas considered dangerous and absurd, and distortion or falsity in some ideas held strongly by social groups to which we belong. People need courage to be fair-minded thinkers in these circumstances. The penalties for nonconformity can be severe.

— Paul, R., author of Knowledge, Belief, and Character: Readings in Virtue Epistemology

As follows, there are many more interpretations of intellectual courage.[11]

First, a more common interpretation is to conceptualise intellectual courage as a component in the family of courage, together with social courage and physical courage.[12]

On the other hand, the execution of cognitive thoughts mostly require the combined involvement of not only the intellectual courage as discussed above, but also the extension of moral courage, and philosophical courage, to eventually turn into cognitive actions.[2]

It has also been said that intellectual courage serves as a "character strength",[1] along with other personality aspects such as self-generated curiosity and open-mindedness.[1]

The development is said to be a highly iterative process, stemmed from the collective and ongoing influence of daily happenings and exposure, such as one's social surroundings and environment.[5] As such, these traits are very implicitly formed, and explains the varying degrees of intellectual courage present in each and every individual.[13]

Manifestation

Virtues have been a topic at hand for philosophers from all over the globe, dating back to as far as the Middle Ages.[14]

Although the birth of intellectual virtues specifically, come shortly after, the foundational layer of interpretations can be traced all the way to ancient Roman, Greek and Latin philosophical theories and traditions,[14] with even religions such as Buddhism having their own take and perspective on specific virtues, and what classifies as a virtue.[14] History has proven time and time again that courage does not always take form in its physical and common connotation, but also in its cognitive form, being an attribute that one can possess, as a "courageous thinker".[9]

Ryan, A. claims that intellectual courage is also widely used and present in political situations.[9] This occurs when one demonstrates the notion of sticking with one's proclamation, despite being exposed to unreasonable and counter intuitive influence that is usually filled with non-aligning agendas sprouting from other political parties.[9] The demonstration of intellectual courage in this sense is highly sought after as a leader and is often followed by new found heights of respect from people.[9]

A more casual day to day situation in which an individual's intellectual courage would arise in, is when contemplation between more than two pathways are present, and the usage of knowledge and reasoning is crucial.[15] Many aspects and foreseeable situations must then be carefully assessed to confidently single out the best possible route.[9] This can then be backed up and weighed upon factors such as the chosen option being one of either the most ethical, the most logical, the most reasonable, or the most beneficial to the individual.[15][1]

Intellectual courage is highly compared and dependent on a person's self-reliance.[16]

Teachings of Intellectual Courage

At present, there is still a withstanding lack of awareness in regards to the vitalness of intellectual courage, to complement the journey of an individual's growth.[4] Many philosophical writers have identified the rising need for intellectual virtues such as intellectual courage, to be taught in education systems as part of expanding the knowledge in mind.[4]

Intellectual courage serves as one of the most important personal traits that encourages life-long learning,[4] a mindset that is promoted in most educational institutions.[4]

Paul, R. criticises most of the present schooling systems starting from elementary school all the way up until college and tertiary education, as institutions that educate students for years without endowing any form of intellectual virtues upon students at the end when they leave.[8] An example of this would be that students can easily become high achievers in school by memorising concepts and taking notes religiously, yet do not truly understand the underlying reasonings behind each concept, and thus would not understand the usefulness and applications outside the education system.[3]

He also believes that the inclusion of this criteria and the possible implementation of teaching intellectual values in the future will henceforth change the parameters of conventional determinants of success and failure in the learning space.[8]

Nordby, S., who holds a philosophy PhD from the University of Oklahoma, also speaks up about the importance of integrating intellectual courage into the minds of thinkers.[17] She states, "when done with parity, it can keep disciplines from becoming insular and reduce the number of echo chambers in academia".[17]

Intellectual courage is part of the mix towards a "disciplined mind" including the other traits: Intellectual integrity, Intellectual humility, Intellectual sense of justice, Intellectual perseverance, Intellectual fair-mindedness, Intellectual confidence in reason, Intellectual empathy and Intellectual autonomy.[3]

With the collective presence of these traits, not only will the individual ultimately achieve higher critical skills, but also higher quality of thought and higher order of thinking.[3]

The opposite of achieving intellectual courage is often referred to as intellectual arrogance, which induces weak critical thinking.[8][3]

A common scenario for intellectual arrogance to arise, is during the process of taking in what Paul, R. describes as "superficially absorbed content" which inevitably stems from "shallow coverage" education.[8]

This inhibits the parameters of which an individual would think, because not only does it hinder open-mindedness towards new and unconventional problems,[8] but it also hinders the willingness to take risks in new ventures, which as a result, opts the individual to stay within the boundaries of norms and safety nets instead, allowing for very little room for growth.[8]

History in Greek Philosophy

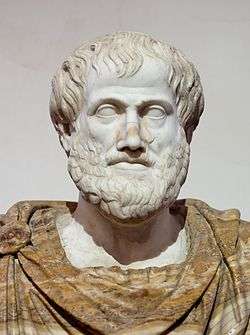

Many great philosophers of all times such as Aristotle, Plato, Socrates, have all touched up upon intellectual courage through discussion of the larger picture, intellectual virtues.[1]

Aristotle is a well known figure in Greek philosophy[18] who has extensively written on virtues such as intellectual courage in his books, Eudemian Ethics and Nicomachean Ethics. As Ryan, A. writes, Aristotle defines courage as "the virtue that occupies a mean between cowardice and recklessness".[9]

Although initially insinuating the physical and literal conception of courage, Aristotle does not exclude the discussion of the terminology in the less straightforward sense.

Aristotle makes a connection for morality and intellectual virtues in being collectively exhaustive,[6] in order to achieve the fulfilment of reading a situation to the best of abilities and thus coming to a sound and righteous conclusion.[6] The act of displaying intellectual courage in this sense, would be to stand one's ground in the situation where in a conflict of interest arises. This will in turn, result in an expense or an opportunity cost, inducing a vital decision making road block (a drawback is present), in choosing the most righteous and moral conclusion.[9]

Plato, a philosopher who is famously known for his work on the Republic,[19] has also extensively written and discussed the virtues of courage, including intellectual courage in his early written works.[7] Devereux, D. claims that Plato has even gone as far as to "single out courage for special treatment".[7] Plato compares a shortfall of intellectual courage as a prevalence of simply a "weakness of will".[7]

Socrates too, is a classical Greek philosopher, known for manifesting the Socratic irony and the Socratic method.[20] Prior to Socrates' written views on intellectual courage, Schmid, W. states that there were predominantly two conventional interpretations of courage in Ancient Greece.[21]

The first conception was that derived from a military point of view, with the "greatest literacy representatives" being ancient heroes such as Achilles, Diomedes and Hector.[21]

The second conception came into realisation as the Greek society's perception and stage on warfare shifted, leading up to courage being defined as "the willingness of the citizen-soldier to stand and fight in the battle line".[22]

Being defined entirely in forms of the physical courage during early times, the introduction towards intellectual courage in the mind came much later, where it was used to describe the cognitive thoughts of the warriors.[21]

Role in Mathematical Creativity

This section is purely to define intellectual courage in the perspective of mathematicians, and aims to demonstrate the underlying relationship between one's intellectual courage in contrast to their respective mathematical creativity.[12]

In reference to Hadar, N. and Kleiner, I.'s 20 year long research, it has been shown that academic privilege is in fact, not the only factor that contributes to the minds of mathematically talented students.[12] This is seen from delving deeper into not just the end results that mathematicians establish, but the actual process and the emotional investment that is put into each practice.[23]

While personal traits and characteristics such as curiosity and the amount of passion and drive one possesses have widely been discussed among the community to be additional contributing factors,[24] intellectual courage, proved to play a crucial and notable role in the success of mathematicians as well.[23] Although a drawback from this study would be the complexity of obtaining and quantifying the emotional and intangible efforts put into the events that eventually lead up to the assertion of new findings,[12] Hadar and Kleiner have ensured that the methods of data collection they have sought after and utilised, will provide a sound and accurate result and representation of the study.[12]

The act of intellectual courage in this perspective entails 4 main key drivers: persistence, self-confidence, insight and motivation.[25]

With all these drivers co-existing, intellectual courage will come into play at the time when an individual experiences a situation that is coupled with the presence of risk and the uncertainty of a finish line.[12] In other words, it is simply to take the risk of putting in an ample amount of time and resource into something that may lead to nothing.[24]

Being aware that there are two possible outcomes for the investment of effort put into said experience,[23] and accepting that their efforts may go unrewarded, is what mathematicians describe as taking a leap with intellectual courage.[12]

References

- Baehr, Jason (2011-06-30). Intellectual Courage. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199604074.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-172930-0.

- Brady, Michael S. (2018-02-22). Snow, Nancy E (ed.). "Moral and Intellectual Virtues". The Oxford Handbook of Virtue. 1. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199385195.013.8.

- "Chapter 3. Becoming a Fairminded Thinker - Critical Thinking: Tools for Taking Charge of Your Professional and Personal Life, Second Edition [Book]". www.oreilly.com. Retrieved 2019-05-31.

- Baehr, Jason (2013). "Educating for Intellectual Virtues: From Theory to Practice". Journal of Philosophy of Education. 47 (2): 248–262. doi:10.1111/1467-9752.12023. ISSN 1467-9752.

- Ritchhart, R. (2002). Intellectual character: What it is, why it matters, and how to get it. John Wiley & Sons.

- Aristotle; Kenny, Anthony (2011-07-14). The Eudemian Ethics. Oxford World's Classics. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-958643-1.

- Devereux, Daniel (1977). "Courage and Wisdom in Plato's Laches". Journal of the History of Philosophy. 15 (2): 129–141. doi:10.1353/hph.2008.0611. ISSN 1538-4586.

- Axtell, Guy (2000). Knowledge, Belief, and Character: Readings in Virtue Epistemology. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8476-9653-6.

- Ryan, Alan (2004). "Intellectual Courage". Social Research. 71 (1): 13–28. ISSN 0037-783X. JSTOR 40971657.

- Anderson, Christopher J. (2003). "The psychology of doing nothing: Forms of decision avoidance result from reason and emotion". Psychological Bulletin. 129 (1): 139–167. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.139. ISSN 1939-1455. PMID 12555797.

- Zavaliy, Andrei G.; Aristidou, Michael (2014-04-03). "Courage: A Modern Look at an Ancient Virtue". Journal of Military Ethics. 13 (2): 174–189. doi:10.1080/15027570.2014.943037. ISSN 1502-7570.

- Movshovitz-Hadar, Nitsa, and I. S. R. A. E. L. Kleiner. "Intellectual courage and mathematical creativity." Creativity in mathematics and education of gifted students (2009): 31-50.

- "PsycNET". psycnet.apa.org. Retrieved 2019-05-12.

- Snow, Nancy E. (2017-12-06). Snow, Nancy E. (ed.). Introduction. The Oxford Handbook of Virtue. 1. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199385195.013.49.

- Stocker, Michael (2009-12-03). Intellectual and Other Nonstandard Emotions. The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy of Emotion. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199235018.003.0019.

- Emerson, Ralph Waldo, 1803-1882. (1909). Essay on self-reliance. Caxton Society. OCLC 36819287.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "An Apology for the Gadfly by S.N. Nordby". BLOGOS. 2018-05-01. Retrieved 2019-05-29.

- Greco, John; Zagzebski, Linda (2000). "Two Kinds of Intellectual Virtue". Philosophy and Phenomenological Research. 60 (1): 179. doi:10.2307/2653438. ISSN 0031-8205. JSTOR 2653438.

- "Plato | Life, Philosophy, & Works". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-05-29.

- Guthrie, W. K. C. (1971). Socrates. London: Cambridge University Press.

- Schmid, W. Thomas (1985). "The Socratic Conception of Courage". History of Philosophy Quarterly. 2 (2): 113–129. ISSN 0740-0675. JSTOR 27743716.

- Burstein, Stanley M.; Littman, Robert J. (August 1975). "The Greek Experiment: Imperialism and Social Conflict, 800-400 B. C.". The History Teacher. 8 (4): 656. doi:10.2307/492690. ISSN 0018-2745. JSTOR 492690.

- Voskoglou, M. G. (2008). Problem-Solving in Mathematics Education: Recent Trends and Development. Quaderni di Ricerca in Didattica (Scienze Matematiche), 18, 22-28.

- Amoozegar, A., Daud, S. M., Mahmud, R., & Jalil, H. A. (2017). Exploring Learner to Institutional Factors and Learner Characteristics as a Success Factor in Distance Learning.

- Meissner, Hartwig; Heid, M. Kathleen; Higginson, William; Saul, Mark; Kurihara, Hideyuki; Becker, Jerry (2004), "TSG 16: Creativity in Mathematics Education and the Education of Gifted Students", Proceedings of the Ninth International Congress on Mathematical Education, Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 343–346, doi:10.1007/1-4020-7910-9_86, ISBN 140208093X