Indochinese tiger

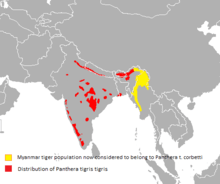

The Indochinese tiger (Panthera tigris tigris) is a tiger population native to Southeast Asia.[2] This population occurs in Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, Cambodia and southwestern China. It has been listed as Endangered on the IUCN Red List since 2008, as the population seriously declined and approaches the threshold for Critically Endangered. As per 2011, the population was thought to comprise 342 individuals, including 85 in Myanmar, and 20 in Vietnam, with the largest population unit surviving in Thailand estimated at 189 to 252 individuals during 2009 to 2014. It is considered extinct in Cambodia.[1]

| Indochinese tiger | |

|---|---|

| |

| Indochinese tiger at Berlin Zoological Garden | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Pantherinae |

| Genus: | Panthera |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | P. t. tigris |

| Trinomial name | |

| Panthera tigris tigris | |

| |

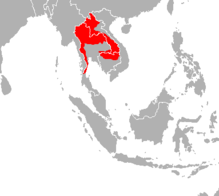

| Distribution of the Indochinese tiger (excluding Myanmar) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

P. t. corbetti Mazák, 1968 | |

Taxonomy

Panthera tigris corbetti was the scientific name proposed by Vratislav Mazák in 1968 based on skin colouration, marking pattern and skull dimensions. It was named in honor of Jim Corbett.[3]

In 2017, the Cat Classification Task Force of the Cat Specialist Group revised felid taxonomy, and now recognizes the tiger populations of mainland South and Southeast Asia as belonging to the nominate subspecies P. tigris tigris.[2] Results of a genetic study published in 2018 supported six monophyletic clades based on whole-genome sequencing analysis of 32 tiger specimens. The specimens from Malaysia and Indochina appeared to be distinct from other mainland Asian populations, thus supporting the concept of six living subspecies.[4]

The tiger population in Peninsular Malaysia is known as the Malayan tiger.[5]

Characteristics

The Indochinese tiger's skull is smaller than that of the Bengal tiger; the ground colouration is darker with more rather short and narrow single stripes.[3][6] In body size, it is smaller than Bengal and Siberian tigers. Males range in size from 255 to 285 cm (100 to 112 in) and in weight from 150 to 195 kg (331 to 430 lb). Females range in size from 230 to 255 cm (91 to 100 in) and in weight from 100 to 130 kg (220 to 290 lb).[7]

Distribution and habitat

The Indochinese tiger is distributed in Myanmar, Thailand and Laos.[1] It has not been recorded in Vietnam since 1997.[8] Available data suggest that there are no more breeding tigers left in Cambodia and China.[9]

In Myanmar, the presence of tigers was confirmed in the Hukawng Valley, Htamanthi Wildlife Sanctuary, and in two small areas in the Tanintharyi Region. The Tenasserim Hills is an important area, but forests are harvested there.[10] In 2015, tigers were recorded by camera-traps for the first time in the hill forests of Karen State.[11]

More than half of the total population survives in the Western Forest Complex in Thailand, especially in the area of the Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary. This habitat consists of tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests.[12] Camera trap surveys from 2008 to 2017 in eastern Thailand detected about 17 adult tigers in an area of 4,445 km2 (1,716 sq mi) in Dong Phayayen-Khao Yai Forest Complex. Several individuals had cubs. The population density in Thap Lan National Park and Pang Sida National Park has been estimated at 0.32–1.21 individuals per 100 km2 (39 sq mi).[13]

In Laos, 14 tigers were documented in Nam Et-Phou Louey National Protected Area during surveys from 2013 to 2017 covering four blocks of about 200 km2 (77 sq mi) semi-evergreen and evergreen forest that are interspersed with some patches of grassland.[14]

In China, it occurred historically in Yunnan province and Mêdog County, where it probably does not survive any more today.[15] In Yunnan's Shangyong Nature Reserve, three individuals were detected during surveys from 2004 to 2009.[16]

Results of a phylogeographic study using 134 samples from tigers across the global range suggest that the historical northwestern distribution limit of the Indochinese tiger is the region in the Chittagong Hills and Brahmaputra River basin, bordering the range of the Bengal tiger.[17][18] Manas-Namdapha, Orang-Laokhowa and Kaziranga-Meghalaya are Tiger Conservation Units in northeastern India, stretching over at least 14,500 km2 (5,600 sq mi) across several protected areas.[19] Tigers are also present in Pakke Tiger Reserve.[20] In the Mishmi Hills, tigers were recorded in 2017 up to an elevation of 3,630 m (11,910 ft) in snow.[21]

In southeastern Tibet, tigers were photographed in Medog County during a camera trapping survey in 2018.[22]

Ecology and behaviour

In Thailand's Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary, seven female and four male tigers were equipped with GPS radio collars between June 2005 and August 2011. Females had a mean home range of 70.2 ± 33.2 km2 (27.1 ± 12.8 sq mi) and males of 267.6 ± 92.4 km2 (103.3 ± 35.7 sq mi).[23] Between 2013 and 2015, 11 prey species were identified at 150 kill sites. Prey species ranged in weight from 3 to 287 kg (6.6 to 632.7 lb), with adult Sambar deer, banteng, gaur and wild boar being the most frequently killed species. Remains of Asiatic elephant calves, hog badger, porcupine, muntjac, serow, pangolin and langur species were also found.[24]

Threats

The primary threat to the tiger is poaching for the illegal wildlife trade.[1] Tiger bone has been an ingredient in traditional Chinese medicine since more than 1500 years and is either added to medicinal wine, used in the form of powder or boiled to a glue-like consistency. More than 40 different formulae containing tiger bone were produced by at least 226 Chinese companies in 1993.[25] Tiger bone glue is a popular medicine among urban Vietnamese consumers.[26]

Between 1970 and 1993, South Korea imported 607 kg (1,338 lb) of tiger bones from Thailand and 2,415 kg (5,324 lb) from China between 1991 and 1993.[27] Between 2001 and 2010, wildlife markets were surveyed in Myanmar, Thailand and Laos. During 13 surveys, 157 body parts of tigers were found, representing at least 91 individuals. Whole skins were the most commonly traded parts. Bones, paws and penises were offered as aphrodisiacs in places with a large sex industry. Tiger bone wine was offered foremost in shops catering to Chinese customers. Traditional medicine accounted for a large portion of products sold and exported to China, Laos and Vietnam.[28]

Between January 2000 and December 2011, 641 tigers, both live and dead, were seized in 196 incidents in Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, Cambodia and China; 275 tigers were suspected to have leaked into trade from captive facilities. China was the most common destination of the seized tigers.[29]

In Myanmar's Hukaung Valley, the Yuzana Corporation alongside local authorities has expropriated more than 200,000 acres (81,000 ha) of land from more than 600 households since 2006. Much of the trees have been logged and the land has been transformed into plantations. Some of the land taken by the Yazana Corporation had been deemed tiger transit corridors. These are areas of land that were supposed to be left untouched by development in order to allow the region's Indochinese tigers to travel between protected pockets of reservation land.[30]

Conservation

Since 1993, the Indochinese tiger is listed on CITES Appendix I, making international trade illegal. China, South Korea, Vietnam, Singapore and Taiwan banned trade in tigers and sale of medicinal derivatives. Manufacture of tiger-based medicine was banned in China, and the open sale of tiger-based medicine reduced significantly since 1995.[31]

Patrolling in Thailand's Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary has been intensified since 2006 so that poaching appears to have reduced, resulting in a marginal improvement of tiger survival and recruitment.[32]

In captivity

The Indochinese tiger is the least represented in captivity and is not part of a coordinated breeding program. As of 2007, 14 individuals were recognized as Indochinese tigers based on genetic analysis of 105 captive tigers in 14 countries.[33]

National Geographic Society News Watch contributor Jordan Schaul wrote in 2010:

Prior to the designation of the Malay subspecies there were approximately 60 Indochinese tigers in Asian, European and North American zoos. Today there are less than a handful. Zoos are committed to conserving the genetic integrity of the subspecies that do exist in the wild.[34]

See also

Tiger populations: Bengal tiger · Siberian tiger · Sumatran tiger · South Chinese tiger · Caspian tiger · Bali tiger · Javan tiger

References

- Goodrich, J.; Lynam, A.; Miquelle, D.; Wibisono, H.; Kawanishi, K.; Pattanavibool, A.; Htun, S.; Tempa, T.; Karki, J.; Jhala, Y. & Karanth, U. (2015). "Panthera tigris". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T15955A50659951.

- Kitchener, A. C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Eizirik, E.; Gentry, A.; Werdelin, L.; Wilting, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Abramov, A. V.; Christiansen, P.; Driscoll, C.; Duckworth, J. W.; Johnson, W.; Luo, S.-J.; Meijaard, E.; O’Donoghue, P.; Sanderson, J.; Seymour, K.; Bruford, M.; Groves, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Nowell, K.; Timmons, Z.; Tobe, S. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group" (PDF). Cat News (Special Issue 11): 66–68.

- Mazák, V. (1968). "Nouvelle sous-espèce de tigre provenant de l'Asie du sud-est". Mammalia. 32 (1): 104−112. doi:10.1515/mamm.1968.32.1.104.

- Liu, Y.-C.; Sun, X.; Driscoll, C.; Miquelle, D. G.; Xu, X.; Martelli, P.; Uphyrkina, O.; Smith, J. L. D.; O’Brien, S. J.; Luo, S.-J. (2018). "Genome-wide evolutionary analysis of natural history and adaptation in the world's tigers". Current Biology. 28 (23): 3840–3849. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2018.09.019. PMID 30482605.

- Kawanishi, K. (2015). "Panthera tigris subsp. jacksoni". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T136893A50665029.

- Mazák, V.; Groves, C. P. (2006). "A taxonomic revision of the tigers (Panthera tigris) of Southeast Asia". Mammalian Biology. 71 (5): 268–287. doi:10.1016/j.mambio.2006.02.007.

- Mazák, V. (1981). "Panthera tigris" (PDF). Mammalian Species. 152 (152): 1–8. doi:10.2307/3504004. JSTOR 3504004.

- Lynam, A.J. (2010). "Securing a future for wild Indochinese tigers: transforming tiger vacuums into tiger source sites". Integrative Zoology. 5 (4): 324–334. doi:10.1111/j.1749-4877.2010.00220.x.

- Walston, J.; Robinson, J. G.; Bennett, E. L.; Breitenmoser, U.; da Fonseca, G. A. B.; Goodrich, J.; Gumal, M.; Hunter, L.; Johnson, A.; Karanth, K.U. & Leader-Williams, N. (2010). "Bringing the Tiger Back from the Brink—The Six Percent Solution". PLOS Biology. 8 (9): e1000485. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000485. PMC 2939024. PMID 20856904.

- Lynam, A. J.; Saw Tun Khaing & Khin Maung Zaw (2006). "Developing a national tiger action plan for the Union of Myanmar". Environmental Management. 37 (1): 30–39. doi:10.1007/s00267-004-0273-9.

- Saw Sha Bwe Moo; Froese, G. Z. L. & Gray, T. N. E. (2017). "First structured camera-trap surveys in Karen State, Myanmar, reveal high diversity of globally threatened mammals". Oryx. 52 (3): 537–543. doi:10.1017/S0030605316001113.

- Simcharoen, S.; Pattanavibool, A.; Karanth, K. U.; Nichols, J. D. & Kumar, N. S. (2007). "How many tigers Panthera tigris are there in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary, Thailand? An estimate using photographic capture-recapture sampling". Oryx. 41 (4): 447–453. doi:10.1017/S0030605307414107.

- Ash, E.; Hallam, C.; Chanteap, P.; Kaszta, Ż.; Macdonald, D.W.; Rojanachinda, W.; Redford, T. & Harihar, A. (2020). "Estimating the density of a globally important tiger (Panthera tigris) population: Using simulations to evaluate survey design in Eastern Thailand". Biological Conservation. 241: 108349. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2019.108349.

- Rasphone, A.; Kéry, M.; Kamler, J.F. & Macdonald, D.W. (2019). "Documenting the demise of tiger and leopard, and the status of other carnivores and prey, in Lao PDR's most prized protected area: Nam Et-Phou Louey". Global Ecology and Conservation. 20: e00766. doi:10.1016/j.gecco.2019.e00766.

- Kang, A.; Xie, Y.; Tang, J.; Sanderson, E. W.; Ginsburg, J. R. & Zhang, E. (2010). "Historic distribution and the recent loss of tigers in China". Integrative Zoology. 5 (4): 335–341. doi:10.1111/j.1749-4877.2010.00221.x.

- Feng, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, B.; Smith, J.L. & Zhang, L. (2013). "Population status of the Indochinese tiger (Panthera tigris corbetti) and density of the three primary ungulate prey species in Shangyong Nature Reserve, Xishuangbanna, China". Acta Theriologica Sinica. 33 (4): 308–318.

- Luo, S.-J.; Kim, J.-H.; Johnson, W. E.; van der Walt, J.; Martenson, J.; Yuhki, N.; Miquelle, D. G.; Uphyrkina, O.; Goodrich, J. M.; Quigley, H. B.; Tilson, R.; Brady, G.; Martelli, P.; Subramaniam, V.; McDougal, C.; Hean, S.; Huang, S.-Q.; Pan, W.; Karanth, U. K.; Sunquist, M.; Smith, J. L. D. & O'Brien, S. J. (2004). "Phylogeography and genetic ancestry of tigers (Panthera tigris)". PLoS Biology. 2 (12): e442. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020442. PMC 534810. PMID 15583716.

- Luo, S.J.; Johnson, W. E. & O'Brien, S. J. (2010). "Applying molecular genetic tools to tiger conservation". Integrative Zoology. 5 (4): 351–362. doi:10.1111/j.1749-4877.2010.00222.x. PMC 6984346. PMID 21392353.

- Wikramanayake, E.D.; Dinerstein, E.; Robinson, J.G.; Karanth, K.U.; Rabinowitz, A.; Olson, D.; Mathew, T.; Hedao, P.; Connor, M.; Hemley, G. & Bolze, D. (1999). "Where can tigers live in the future? A framework for identifying high-priority areas for the conservation of tigers in the wild". In Seidensticker, J.; Christie, S. & Jackson, P. (eds.). Riding the Tiger: Tiger Conservation in Human-Dominated Landscapes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 255–272. ISBN 978-0-521-64835-6.

- Chauhan, D. S.; Singh, R.; Mishra, S.; Dadda, T. & Goyal, S. P. (2006). Estimation of tiger population in an intensive study area of Pakke Tiger Reserve, Arunachal Pradesh, India. Dehradun, India: Wildlife Institute of India.

- Adhikarimayum, A. S. & Gopi, G. V. (2018). "First photographic record of tiger presence at higher elevations of the Mishmi Hills in the Eastern Himalayan Biodiversity Hotspot, Arunachal Pradesh, India". Journal of Threatened Taxa. 10 (13): 12833–12836. doi:10.11609/jott.4381.10.13.12833-12836.

- Li, X.; Bleisch, W.V.; Liu, X. & Jiang, X. (2020). "Camera-trap surveys reveal high diversity of mammals and pheasants in Medog, Tibet". Oryx: first view. doi:10.1017/S0030605319001467.

- Simcharoen, A.; Savini, T.; Gale, G. A.; Simcharoen, S.; Duangchantrasiri, S.; Pakpien, S. & Smith, J. L. D. (2014). "Female tiger Panthera tigris home range size and prey abundance: important metrics for management". Oryx. 48 (3): 370–377. doi:10.1017/S0030605312001408.

- Pakpien, S.; Simcharoen, A.; Duangchantrasiri, S.; Chimchome, V.; Pongpattannurak, N. & Smith, J. L. D. (2017). "Ecological Covariates at Kill Sites Influence Tiger (Panthera tigris) Hunting Success in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary, Thailand". Tropical Conservation Science. 10: 1940082917719000. doi:10.1177/1940082917719000.

- Li, C. & Zhang, D. (1997). The Research on Substitutes for Tiger Bone. First International Symposium on Endangered Species Used in Traditional East Asian Medicine: Substitutes for Tiger Bone and Musk. Hong Kong: TRAFFIC East Asia and the Chinese Medicinal Material Research Centre.

- Davis, E. O.; Willemsen, M.; Dang, V.; O’Connor, D. & Glikman, J. A. (2020). "An updated analysis of the consumption of tiger products in urban Vietnam". Global Ecology and Conservation. 22: e00960. doi:10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e00960.

- Mills, J. A. & Jackson, P. (1994). Killed for a Cure: A Review of the Worldwide Trade in Tiger Bone (PDF). Cambridge, UK: TRAFFIC International.

- Oswell, A. H. (2010). The Big Cat Trade in Myanmar and Thailand (PDF). Selangor, Malaysia: TRAFFIC Southeast Asia.

- Stoner, S.; Krishnasamy, K.; Wittmann, T.; Delean, S. & Cassey, P. (2016). Reduced to skin and bones re-examined (PDF). Selangor, Malaysia: TRAFFIC Southeast Asia.

- Martov, S. (2012). "World's Largest Tiger Reserve 'Bereft of Cats'". The Irrawaddy. Retrieved 16 October 2013.

- Hemley, G. & Mills, G. A. (1999). "The beginning of the end of tigers in trade?". In Seidensticker, J.; Christie, S. & Jackson, P. (eds.). Riding the Tiger: Tiger Conservation in Human-Dominated Landscapes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 217–229. ISBN 978-0-521-64835-6.

- Duangchantrasiri, S.; Umponjan, M.; Simcharoen, S.; Pattanavibool, A.; Chaiwattana, S.; Maneerat, S.; Kumar, N. S.; Jathanna, D.; Srivathsa, A. & Karanth, K.U. (2016). "Dynamics of a low‐density tiger population in Southeast Asia in the context of improved law enforcement". Conservation Biology. 30 (3): 639–648. doi:10.1111/cobi.12655.

- Luo, S. J.; Johnson, W. E.; Martenson, J.; Antunes, A.; Martelli, P.; Uphyrkina, O.; Traylor-Holzer, K.; Smith, J. L. D. & O'Brien, S. J. (2008). "Subspecies genetic assignments of worldwide captive tigers increase conservation value of captive populations". Current Biology. 18 (8): 592–596. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.03.053.

- Schaul, J. (2010). "Managing Tiger Species Survival in American Zoos". National Geographic Society News Watch. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Indochinese tiger. |

- "Tiger. Northern Indochinese tiger (P. t. corbetti)". IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group.

- "Information on Tigers in the Greater Mekong region". WWF.