Human zoo

Human zoos, also called ethnological expositions, were 19th- and 20th-century public exhibitions of humans, usually in an erroneously labeled "natural" or "primitive" state. The displays often emphasized the cultural differences between Europeans of Western civilization and non-European peoples or with other Europeans who practiced a lifestyle deemed more primitive.[1] Some of them placed indigenous populations in a continuum somewhere between the great apes and Europeans.[2] Ethnological expositions are now seen as highly degrading and racist, depending on the show and individuals involved.

Human zoos in Germany

In the late 19th century, German ethnographic museums[3] were an attempt at empirical study of human culture. They contained artifacts from cultures around the world organized by continent allowing visitors to see the similarities and differences between the groups and form their own ideas. The ethnographic museums of Germany were explicitly designed to steer away from projecting certain principles or instructing its viewers to interpret the material in a particular manner. They were instead left open for museum guests to form their own opinions. The directors of Germany's ethnographic museums intended to create a unifying history of mankind,[3] to show how humans had progressed to the cosmopolitan creatures that walked the halls of these museums.

Ethnology studies in Germany took a new approach in the 1870s as human displays were incorporated into zoos. These exhibits were lauded as educational to the general population by the scientific community of the time, because they were informative of the way that people lived across the world. Very quickly, the exhibits were used as a way to show that Europeans had evolved into a superior cosmopolitan life.

As Ethnogenic expositions were discontinued in Germany around 1931,[4] there were many repercussions for the performers. Many of the people brought from their homelands to work in the exhibits had created families in Germany, and there were many children that had been born in Germany. Once they no longer worked in the zoos or for performance acts, these people were stuck living in Germany where they had no rights and were harshly discriminated against. During the rise of the Nazi party, the foreign actors in these stage shows were typically able to stay out of concentration camps because there were so few of them that the Nazis did not see them as a real threat.[5] Although they were able to avoid concentration camps, they were not able to participate in German life as citizens of ethnically German origin could. The Hitler Youth did not allow children of foreign parents to participate, and adults were rejected as German soldiers.[5] Many ended up working in war industry factories or foreign laborer camps.[5] After World War II ended, racism in Germany became more concealed or invisible, but it did not go away. Many people of foreign descent intended to leave after the war, but because of their German nationality, it was difficult for them to emigrate.[5]

Key influences

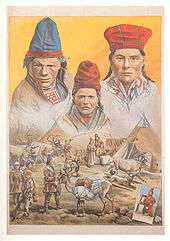

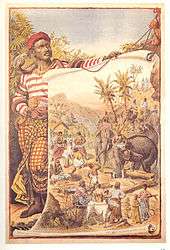

Carl Hagenbeck[6] was a German exotic animal businessman who became famous for his dominating the animal trade market during the mid- to late 1800s. Due to the costs of acquiring and keeping animals, the financial implications started to worry Hagenbeck, and he began looking for other ways to alleviate the company’s monetary strains. Heinrich Leutemann, an old friend of Hagenbeck's, suggested bringing along the people from the foreign lands to accompany the animals. The idea struck Hagenbeck as brilliant and he had a group of Laplanders accompany his next shipment of reindeer. They set up traditional houses and went about their business as usual on the Hagenbeck property. The display was so successful that Carl was organizing his second show before the first one was over. Although the concept of parading peoples captured from conquered lands goes back to the Romans, Hagenbeck claimed to have the first shows displaying “cultures” from foreign lands. Carl Hagenbeck continued to bring indigenous people along with the animals that he was importing from across the globe. The people would come with their hunting equipment, homes, and other facets of their daily life. Hagenbeck’s displays evolved in complexity as the years went by. In 1876, Hagenbeck had a group of 6 Sami accompany a herd of reindeer, and by 1874 his acts included close to 67 men, women, and children in his Ceylon show performing with 25 elephants. The performances also expanded from showing everyday activities such as milking reindeer and building huts, to displaying some of the more extravagant parts of the cultures such as magicians, jugglers, and devil dancers.

First human zoos

The notion of the human curiosity has a history at least as long as colonialism. For instance, in the Western Hemisphere, one of the earliest-known zoos, that of Moctezuma in Mexico, consisted not only of a vast collection of animals, but also exhibited humans, for example, dwarves, albinos and hunchbacks.[7]

During the Renaissance, the Medici developed a large menagerie in the Vatican. In the 16th century, Cardinal Hippolytus Medici had a collection of people of different races as well as exotic animals. He is reported as having a troupe of so-called Savages, speaking over twenty languages; there were also Moors, Tartars, Indians, Turks and Africans.[8]

One of the first modern public human exhibitions was P.T. Barnum's exhibition of Joice Heth on February 25, 1835[9] and, subsequently, the Siamese twins Chang and Eng Bunker. These exhibitions were common in freak shows.[10] Another famous example was that of Saartjie Baartman of the Namaqua, often referred to as the Hottentot Venus, who was displayed in London and France until her death in 1815.

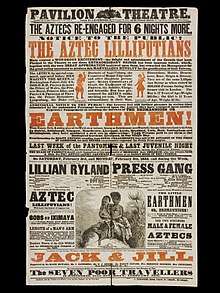

During the 1850s, Maximo and Bartola, two microcephalic children from El Salvador, were exhibited in the US and Europe under the names Aztec Children and Aztec Lilliputians.[11] However, human zoos would become common only in the 1870s in the midst of the New Imperialism period.

1870s to the 1930s

In the 1870s, exhibitions of exotic populations became popular in various countries.[13] Human zoos could be found in Paris, Hamburg, Antwerp, Barcelona, London, Milan, and New York City. Carl Hagenbeck, a merchant in wild animals and future entrepreneur of many zoos in Europe, decided in 1874 to exhibit Samoan and Sami people as "purely natural" populations. In 1876, he sent a collaborator to the Egyptian Sudan to bring back some wild beasts and Nubians. The Nubian exhibit was very successful in Europe and toured Paris, London, and Berlin. In 1880, Hagenbeck dispatched an agent to Labrador to secure a number of Esquimaux (Eskimo / Inuit) from the moravian mission of Hebron; these Inuit were exhibited in his Hamburg Tierpark. Other ethnological expositions included Egyptian and Bedouin mock settlements.[14] Hagenbeck would also employ agents to take part in his ethnological exhibits, with the aim of exposing his audience to various different subsistence modes and lifestyles. Among these hired workers were Hersi Egeh and his lineage from Berbera in present-day northwestern Somalia, who in the process accumulated much wealth, which they later reinvested in real estate in their homeland.[15] The viceroy of India likewise gave Hagenbeck permission to hire local inhabitants for an exhibit, on the condition that Hagenbeck would first have to deposit funds into the royal treasury.[16]

Geoffroy de Saint-Hilaire, director of the Jardin d'acclimatation, decided in 1877 to organize two ethnological spectacles that presented Nubians and Inuit. That year, the audience of the Jardin d'acclimatation' doubled to one million. Between 1877 and 1912, approximately thirty ethnological exhibitions were presented at the Jardin zoologique d'acclimatation.

Both the 1878 and the 1889 Parisian World's Fair presented a Negro Village (village nègre). Visited by 28 million people, the 1889 World's Fair displayed 400 indigenous people as the major attraction. The 1900 World's Fair presented the famous diorama living in Madagascar, while the Colonial Exhibitions in Marseilles (1906 and 1922) and in Paris (1907 and 1931) also displayed humans in cages, often nude or semi-nude. The 1931 exhibition in Paris was so successful that 34 million people attended it in six months, while a smaller counter-exhibition entitled The Truth on the Colonies, organized by the Communist Party, attracted very few visitors—in the first room, it recalled Albert Londres and André Gide's critiques of forced labour in the colonies. Nomadic Senegalese Villages were also presented.

In 1883, native people of Suriname were displayed in the International Colonial and Export Exhibition in Amsterdam, held behind the Rijksmuseum.

In the late 1800s, Hagenbeck organized exhibitions of indigenous populations from various parts of the globe. He staged a public display in 1886 of Sinhalese autochthones from the Sri Lanka. In 1893/1894, he also put together an exhibition of Sami/Lapps in Hamburg-Saint Paul.

At the 1901 Pan-American Exposition[17] and at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition, where Little Egypt performed bellydance, and where the photographers Charles Dudley Arnold and Harlow Higginbotham took depreciative photos, presenting indigenous people as catalogue of "types", along with sarcastic legends.[18]

In 1896, to increase the number of visitors, the Cincinnati Zoo invited one hundred Sioux Native Americans to establish a village at the site. The Sioux lived at the zoo for three months.[19]

In 1904, Apaches and Igorots (from the Philippines) were displayed at the Saint Louis World Fair in association with the 1904 Summer Olympics. The US had just acquired, following the Spanish–American War, new territories such as Guam, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico, allowing them to "display" some of the native inhabitants.[20] According to the Rev. Sequoyah Ade:

To further illustrate the indignities heaped upon the Philippine people following their eventual loss to the Americans, the United States made the Philippine campaign the centrepoint of the 1904 World's Fair held that year in St. Louis, MI [sic]. In what was enthusiastically termed a "parade of evolutionary progress," visitors could inspect the "primitives" that represented the counterbalance to "Civilisation" justifying Kipling's poem "The White Man's Burden". Pygmies from New Guinea and Africa, who were later displayed in the Primate section of the Bronx Zoo, were paraded next to American Indians such as Apache warrior Geronimo, who sold his autograph. But the main draw was the Philippine exhibition complete with full size replicas of Indigenous living quarters erected to exhibit the inherent backwardness of the Philippine people. The purpose was to highlight both the "civilising" influence of American rule and the economic potential of the island chains' natural resources on the heels of the Philippine–American War. It was, reportedly, the largest specific Aboriginal exhibition displayed in the exposition. As one pleased visitor commented, the human zoo exhibition displayed "the race narrative of odd peoples who mark time while the world advances, and of savages made, by American methods, into civilized workers."[21]

In 1906, Madison Grant—socialite, eugenicist, amateur anthropologist, and head of the New York Zoological Society—had Congolese pygmy Ota Benga put on display at the Bronx Zoo in New York City alongside apes and other animals. At the behest of Grant, the zoo director William Hornaday placed Benga displayed in a cage with the chimpanzees, then with an orangutan named Dohong, and a parrot, and labeled him The Missing Link, suggesting that in evolutionary terms Africans like Benga were closer to apes than were Europeans. It triggered protests from the city's clergymen, but the public reportedly flocked to see it.[12][22]

Benga shot targets with a bow and arrow, wove twine, and wrestled with an orangutan. Although, according to The New York Times, "few expressed audible objection to the sight of a human being in a cage with monkeys as companions", controversy erupted as black clergymen in the city took great offense. "Our race, we think, is depressed enough, without exhibiting one of us with the apes", said the Reverend James H. Gordon, superintendent of the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum in Brooklyn. "We think we are worthy of being considered human beings, with souls."[23]

New York City Mayor George B. McClellan Jr. refused to meet with the clergymen, drawing the praise of Hornaday, who wrote to him: "When the history of the Zoological Park is written, this incident will form its most amusing passage."[23]

As the controversy continued, Hornaday remained unapologetic, insisting that his only intention was to put on an ethnological exhibition. In another letter, he said that he and Grant—who ten years later would publish the racist tract The Passing of the Great Race—considered it "imperative that the society should not even seem to be dictated to" by the black clergymen.[23]

On Monday, September 8, 1906, after just two days, Hornaday decided to close the exhibition, and Benga could be found walking the zoo grounds, often followed by a crowd "howling, jeering and yelling."[23]

Between the 1st May and 31st October, 1908 the Scottish National Exhibition, opened by one of Queen Victoria’s grandsons, Prince Arthur of Connaught, was held in Saughton Park, Edinburgh. One of the attractions was the Senegal Village with its French-speaking Senegalese residents, on show demonstrating their way of life, art and craft while living in beehive huts.[24][25]

In 1909, the infrastructure of the 1908 Scottish National Exhibition in Edinburgh was used to contruct the new Marine Gardens to the coast near Edinburgh at Portobello. A group of Somalian men, women and children were shipped over to be part of the exhibition, living in thatched huts.[26][27]

In 1925, a display at Belle Vue Zoo in Manchester, England, was entitled "Cannibals" and featured black Africans depicted as savages.[28]

By the 1930s, a new kind of human zoo appeared in America, nude shows masquerading as education. These included the Zoro Garden Nudist Colony at the Pacific International Exposition in San Diego, California (1935-6) and the Sally Rand Nude Ranch at the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco (1939). The former was supposedly a real nudist colony, which used hired performers instead of actual nudists. The latter featured nude women performing in western attire. The Golden Gate fair also featured a "Greenwich Village" show, described in the Official Guide Book as “Model artists’ colony and revue theatre.”[29]

1940s to the present

A Congolese village was displayed at the Brussels 1958 World's Fair.[30]

In April 1994, an example of an Ivory Coast village was presented as part of an African safari in Port-Saint-Père, near Nantes, in France, later called Planète Sauvage.[31]

In July 2005, the Augsburg Zoo in Germany hosted an "African village" featuring African crafts and African cultural performances. The event was subject to widespread criticism.[32] Defenders of the event argued that it was not racist since it did not involve exhibiting Africans in a debasing way, as had been done at zoos in the past. Critics argued that presenting African culture in the context of a zoo contributed to exoticizing and stereotyping Africans, thus laying the ground work for racial discrimination.[33]

In August 2005, London Zoo displayed four human volunteers wearing fig leaves (and bathing suits) for four days.[34]

In 2007, Adelaide Zoo ran a Human Zoo exhibition which consisted of a group of people who, as part of a study exercise, had applied to be housed in the former ape enclosure by day, but then returned home by night.[35] The inhabitants took part in several exercises, and spectators were asked for donations towards a new ape enclosure.

Also in 2007, pygmy performers at the Festival of Pan-African Music (Fespam) were housed at a zoo in Brazzaville, Congo. Although members of the group of 20 people—among them an infant, age three months—were not officially on display, it was necessary for them to "collect firewood in the zoo to cook their food, and [they] were being stared at and filmed by tourists and passers-by".[36]

In August 2014, as part of the Edinburgh International Festival, South African theatre-maker Brett Bailey's show Exhibit B was performed in the Playfair Library Hall, University of Edinburgh; then in September at The Barbican in London. This explored the nature of Human Zoos and raised much controversy both amongst the performers and the audiences.[37]

With a view to tackling the morality of Human Zoo exhibits, 2018 saw the poster exhibition, Putting People on Display, tour Glasgow School of Art, the University of Edinburgh, the University of Stirling, the University of St Andrews and the University of Aberdeen. Additional posters were added to a selection from the French ACHAC's exhibition, Human Zoos: the Invention of the Savage, in relation to the Scottish dimension in hosting such shows.[38]

References

- Abbattista, Guido; Iannuzzi, Giulia (2016). "World Expositions as Time Machines: Two Views of the Visual Construction of Time between Anthropology and Futurama". World History Connected. 13 (3).

- Lewis, Jurmain, Kilgore (2008). Cengage Advantage Books: Understanding Humans: An Introduction to Physical Anthropology and Archaeology. Cengage Learning. p. 172. ISBN 0495604747.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- H. Glenn, Penny (2002). Objects of Culture Ethnology and Ethnographic Museums in Imperial Germany. University of North Carolina Press.

- Ethnogenic expositions were discontinued in Germany around 1931

- “‘You Better Go Back to Africa’| Interview.” "You Better Go Back to Africa"| Interview, DW English, 18 June 2017, www.youtube.com/watch?v=baGXUsOKBcU.

- Rothfels, Nigel (2012). Savages and Beasts: The Birth of the Modern Zoo. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Mullan, Bob and Marvin Garry, Zoo culture: The book about watching people watch animals, University of Illinois Press, Urbana, Illinois, Second edition, 1998, p.32. ISBN 0-252-06762-2

- Mullan, Bob and Marvin Garry, Zoo culture: The book about watching people watch animals, University of Illinois Press, Urbana, Illinois, Second edition, 1998, p.98. ISBN 0-252-06762-2

- "The Museum of Hoaxes". Archived from the original on 29 May 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

- "On A Neglected Aspect Of Western Racism" by Kurt Jonassohn, December 2000, Montreal Institute for Genocide and Human Rights Studies

- Roberto Aguirre, Informal Empire: Mexico And Central America In Victorian Culture, Univ. of Minnesota Press, 2004, ch. 4

- "Man and Monkey Show Disapproved by Clergy", The New York Times, September 10, 1906.

- Abbattista, Guido (2014). Moving bodies, displaying nations : national cultures, race and gender in world expositions : Nineteenth to Twenty-first century. Trieste: EUT. ISBN 9788883035821. OCLC 898024184.

- Belvedere: Zeitschrift für bildende Kunst, Volume 12. Österreichische Galerie Belvedere. 2006. p. 102. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- Africana Publishing Company (1985). "The International Journal of African Historical Studies". The International Journal of African Historical Studies: 20. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- Davis, Janet M. (2003). The Circus Age: Culture and Society under the American Big Top. University of North Carolina Press. p. 198. ISBN 0807861499. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- See Charles Dudley Arnold's photo Archived 2008-07-05 at the Wayback Machine similar human displays had been seen of six men dressed in Native-American costume, in front and on top of a reconstruction of a Six-Nations Long House.

- Anne Maxell, "Montrer l'Autre: Franz Boas et les soeurs Gerhard", in Zoos humains. De la Vénus hottentote aux reality shows, Nicolas Bancel, Pascal Blanchard, Gilles Boëtsch, Eric Deroo, Sandrine Lemaire, edition La Découverte (2002), pp. 331-339, in part. p. 333,

- Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Garden, Ohio Historical Society.

- Jim Zwick (March 4, 1996). "Remembering St. Louis, 1904: A World on Display and Bontoc Eulogy". Syracuse University. Retrieved 2007-05-25.

- "The Passions of Suzie Wong Revisited, by Rev. Sequoyah Ade". Aboriginal Intelligence. January 4, 2004. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007.

- Bradford, Phillips Verner and Blume, Harvey. Ota Benga: The Pygmy in the Zoo. St. Martins Press, 1992.

- Keller, Mitch (2006-08-06). "The Scandal at the Zoo". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

- Edinburgh City Libraries (25 August 2015). "Saughton's glorious summer of 1908". Tales of One City. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- "Saughton Park". Gazetteer for Scotland. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Freeman, Sarah (12 June 2015). "Portobello, 99 ice creams, and Britains's last seaside heritage: the sweet taste of success". The Independent.

- "1910 Somali Village, Edinburgh Marine Gardens, Portobello". Human Zoos. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- Paul A. Rees, An Introduction to Zoo Biology and Management, Wiley-Blackwell, John Wiley & Sons Ltd., Chichester (West Sussex), 2011, p.44. ISBN 978-1-4051-9349-8

- "Sally Rand and The Music Box", Virtual Museum of San Francisco

- (in French) Cobelco. Belgium human zoo; "Peut-on exposer des Pygmées? [link broken]". Le Soir. July 27, 2002. Archived from the original on February 8, 2005.

- Barlet, Olivier and Blanchard, Pascal, "Le retour des zoos humains", abridged in "Les zoos humains sont-ils de retour?", Le Monde, June 28, 2005. (French)

- (in English and French) "Vers un nouveau zoo humain en Allemagne? (original text in English below the French translation)". Indymedia. December 6, 2005. Archived from the original on March 19, 2013. Retrieved January 21, 2006.; "England Hacks Away at the Shaken EU". Der Spiegel. June 6, 2005.; "A Different View of the Human Zoo". Der Spiegel. June 13, 2005.; "Zoo sparks row over 'tribesmen' props for animals, by Allan Hall". The Scotsman. June 8, 2005.; Critical analysis of the Augsburg human zoo Archived 2006-01-04 at the Wayback Machine ("Organizers and visitors were not racist but they participated in and reflected a process that has been called racialization: the daily and often taken-for-granted means by which humans are separated into supposedly biologically based and unequal categories", etc.)

- Schiller, Nina Glick; Dea, Data; Höhne, Markus (4 July 2005). "African Culture and the Zoo in the 21st Century: The "African Village" in the Augsburg Zoo and Its Wider Implications" (PDF). Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 January 2006.

- London Zoo official website Archived 2006-01-16 at the Wayback Machine;"Humans strip bare for zoo exhibit". BBC News. August 25, 2005. Retrieved January 5, 2010.;"Humans On Display At London's Zoo". CBS News. August 26, 2005.;"The human zoo? by Debra Saunders (a bit more critical)". Townhall. September 1, 2005.

- "Humans on display at Adelaide Zoo". tvnz. January 12, 2007. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014.

- BBC News (2007-07-13). "Pygmy artists housed in Congo zoo". Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- O'Mahony, John (11 August 2014). "Edinburgh's most controversial show: Exhibit B, a human zoo". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- "ACHAC's 'Human Zoos' Exhibition: Scottish University Tour". French at Stirling. 14 June 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

Bibliography and films

- Nicolas Bancel, Pascal Blanchard, Gilles Boëtsch, Eric Deroo, Sandrine Lemaire Zoos humains. De la Vénus hottentote aux reality shows, edition La Découverte (2002) 480 pages (in French) - French presentation of the book here ISBN 2-7071-4401-0

- Anne Dreesbach: Colonial Exhibitions, 'Völkerschauen' and the Display of the 'Other', European History Online, Mainz: Institute of European History, 2012, retrieved: June 6, 2012.

- The Couple in the Cage. 1997. Dir. Coco Fusco and Paula Eredia. 30 min.

- Régis Warnier, the film Man to Man. 2005.

- "From Bella Coola to Berlin". 2006. Dir. Barbara Hager. 48 minutes. Broadcaster—Bravo! Canada (2007).

- "Indianer in Berlin: Hagenbeck's Volkerschau". 2006. Dir. Barbara Hager. Broadcaster—Discovery Germany Geschichte Channel (2007).

- Alexander C. T. Geppert, Fleeting Cities. Imperial Expositions in Fin-de-Siècle Europe (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010).

- Sadiah Qureshi, Peoples on Parade: Exhibitions, Empire and Anthropology in Nineteenth-Century Britain (2011).

- Human zoos. The invention of the savage, Dir. Pascal Blanchard, Gilles Boëtsch, Nanette Jacomijn Snoep - exhibition catalogue - Actes Sud (2011)

- Sauvages. Au cœur des zoos humains, Dir. Pascal Blanchard, Bruno Victor-Pujebet - 90 minutes - Bonne Pioche production & Archipel (2018)

- Human Zoos: America's Forgotten History of Scientific Racism, Dir. John G. West (2019)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Human zoos. |

- Pascal Blanchard, Sandrine Lemaire and Nicolas Bancel (August 2000). "Human zoos - Racist theme parks for Europe's colonialists". Le Monde Diplomatique.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link); "Ces zoos humains de la République coloniale" (in French). Le Monde Diplomatique. August 2000. (available to everyone)

- "On A Neglected Aspect Of Western Racism", by Kurt Jonassohn, December 2000 (Jonassohn is known for his book with Frank Chalk, The history and sociology of genocide : analyses and case studies, 1990, Yale University Press; New Haven)

- The Colonial Exposition of May 1931 by Michael Vann

- May 2003 Symposium "Human Zoos or the exhibition of the creature" (in French)

- Guido Abbattista, Africains en exposition (Italie XIXe siècle) entre racialisme, spectacularité et humanitarisme (in French)

- "Official site of the Adelaide Human Zoo"

- Qureshi, Sadiah (2004), 'Displaying Sara Baartman, the 'Hottentot Venus', History of Science 42:233-257. Available online at Science History Publications.