House of Bamboo

House of Bamboo is a 1955 American film noir shot in CinemaScope and DeLuxe Color. It was directed and co-written by Samuel Fuller.[3]

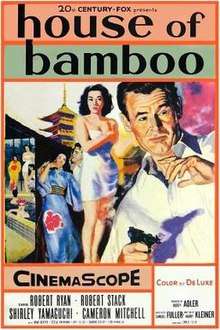

| House of Bamboo | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Samuel Fuller |

| Produced by | Buddy Adler |

| Screenplay by | Harry Kleiner Samuel Fuller |

| Starring | Robert Ryan Robert Stack Shirley Yamaguchi Cameron Mitchell |

| Music by | Leigh Harline |

| Cinematography | Joseph MacDonald |

| Edited by | James B. Clark |

Production company | 20th Century Fox |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release date |

|

Running time | 102 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1,380,000[1] |

| Box office | $1.7 million (US)[2] |

The film is a loose remake of The Street with No Name (1948), using the same screenwriter (Harry Kleiner) and cinematographer (Joseph MacDonald).

Plot

In 1954, a military train guarded by American soldiers and Japanese police is robbed of its cargo of guns, ammunition, and smoke bombs. Five weeks later, a thief named Webber lies dying in a Tokyo hospital, shot by one of his own cohorts during a holdup in which smoke bombs were used. Webber is questioned by military and police investigators, but he refuses to implicate his fellow gang members. Webber does reveal, however, that he is secretly married to a Japanese woman named Mariko. Police discover among Webber's possessions a letter from an American named Eddie Spanier, who wants to join Webber in Japan after his release from a U.S. prison.

Three weeks later, Spanier arrives in Tokyo and makes contact with Mariko, gaining her trust with a photograph of himself taken with Webber. Later, Spanier goes to a pachinko parlor, attempting to sell "protection" to the manager. But when he tries to shake down another parlor, he is beaten by a group of Americans led by racketeer Sandy Dawson, who is so intrigued with Spanier's audacity that he later arranges for him to join his gang, a disgruntled group of former American servicemen who have been dishonorably discharged. After being accepted into the gang, Spanier secretly meets with U.S. and Japanese investigators, for whom he is actually working undercover. To solidify his cover, Spanier asks Mariko to live with him as his "kimono girl." Hoping to discover who killed Webber, Mariko consents to Spanier's offer. In the meantime, Dawson grows to trust Spanier and even saves his life when Eddie is wounded during a robbery.

Spanier finally informs Mariko of his real identity as an undercover infiltrator into the Dawson gang. And when Charlie, one of Dawson's men spies Mariko meeting with an American army officer to fill him in on the details of the Dawson gang's next heist, he notifies Dawson. The job is thus aborted, but an outside informant reveals to Dawson that (a) the police are poised to capture him and that (b) Spanier is a military plant. Dawson thus sets up Spanier's death, but that plan backfires. Dawson is chased by the police to a rooftop amusement park. After an intense gunfight, Spanier shoots and kills Dawson.

Cast

- Robert Ryan as Sandy Dawson

- Robert Stack as Eddie Spanier

- Shirley Yamaguchi as Mariko

- Cameron Mitchell as Griff

- Brad Dexter as Capt. Hanson

- Sessue Hayakawa as Inspector Kitz

- DeForest Kelley as Charlie

- Biff Elliot as Webber

- Sandro Giglio as Ceram

- Elko Hanabusa as Japanese Screaming Woman

Background

The narration at the film's beginning tells the viewer that the film was photographed entirely on location in Tokyo, Yokohama, and the Japanese countryside. At movie's end, an acknowledgments credit thanks "the Military Police of the U.S. Army Forces Far East and the Eighth Army, as well as the Government of Japan and the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department" for their cooperation with the film's production.

The film was one of a number of 20th Century Fox movies produced by Buddy Adler being shot on location in Asia around this time. Others included Soldier of Fortune, The Left Hand of God and Love is a Many Splendored Thing.[4] It was the second Cinemascope Fox film that Samuel Fuller made for the studio.Fuller, Stack and Yamaguchi arrived in Japan on 26 January 1955.[5]

Reception

Critical response

The staff of Variety magazine wrote of the film, "Novelty of scene and a warm, believable performance by Japanese star Shirley Yamaguchi are two of the better values in the production. Had story treatment and direction been on the same level of excellence, House would have been an all round good show. Pictorially, the film is beautiful to see; the talk's mostly in the terse, tough idiom of yesteryear mob pix."[6]

Film critic Keith Uhlich believes the film is an excellent example of wide-screen photography. He wrote in a review, "Quite simply, House of Bamboo has some of the most stunning examples of widescreen photography in the history of cinema. Traveling to Japan on 20th Century Fox's dime, Fuller captured a country divided, trapped between past traditions and progressive attitudes while lingering in the devastating aftereffects of an all-too-recent World War. His visual schema represents the societal fractures through a series of deep-focus, Non-theatrical tableaus, a succession of silhouettes, screens, and stylized color photography that melds the heady insanity of a Douglas Sirk melodrama (see, as an especial point of comparison, Sirk's 1956 Korea-set war film Battle Hymn) with the philosophical inquiry of the best noirs."[7]

For many years after its initial release, the film was only seen on TV in pan-and-scan prints, leading people to believe that DeForest Kelley has a small role near the end of the film. When Fox finally struck a new 35mm CinemaScope print for a film festival in the 1990s, viewers were surprised to see that Kelley was in the film all the way through—he was just always off to one side and thus had been panned out of the frame.

References in other films

A scene from House of Bamboo is briefly shown prominently, but enigmatically, in the 2002 film Minority Report.

See also

References

- Aubrey Solomon, Twentieth Century Fox: A Corporate and Financial History, Scarecrow Press, 1989, p 249.

- 'The Top Box-Office Hits of 1955', Variety Weekly, January 25, 1956.

- House of Bamboo at the American Film Institute Catalog.

- Schallert, Edwin (Jan 5, 1955). "Anson Bond, Eddie Rio Plan Super Packaging; King to Direct Jennifer". Los Angeles Times. p. B7.

- "Three Film Stars in Tokyo". New York Times. Jan 27, 1955. p. 17.

- Film review Variety, July 1, 1955. Accessed: August 2, 2013.

- Uhlich, Keith film/DVD review. Slant magazine, 2005. Accessed: August 2, 2013.

Bibliography

- Provencher, Ken (Spring 2014). "Bizarre Beauty: 1950s Runaway Production in Japan". Velvet Light Trap. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press (73): 39–50. doi:10.7560/VLT7304. ISSN 1542-4251.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- House of Bamboo at the American Film Institute Catalog

- House of Bamboo on IMDb

- House of Bamboo at Rotten Tomatoes

- House of Bamboo at AllMovie

- House of Bamboo at the TCM Movie Database

- House of Bamboo film trailer at YouTube