History of the Shroud of Turin

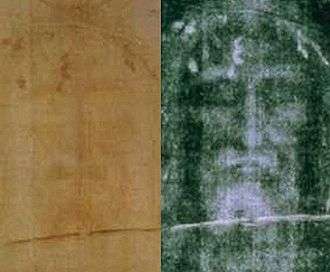

The historical records for the Shroud of Turin can be separated into two time periods: before 1390 and from 1390 to the present. The period until 1390 is subject to debate and controversy among historians. Prior to the 14th century there are some allegedly congruent but controversial references such as the Pray Codex. It is often mentioned that the first certain historical record dates from 1353 or 1357.[1][2] However the presence of the Turin Shroud in Lirey, France, is only undoubtedly attested in 1390 when Bishop Pierre d'Arcis wrote a memorandum where he charged that the Shroud was a forgery.[3] The history from the 15th century to the present is well documented. In 1453 Margaret de Charny deeded the Shroud to the House of Savoy. As of the 17th century the shroud has been displayed (e.g. in the chapel built for that purpose by Guarino Guarini[4]) and in the 19th century it was first photographed during a public exhibition.

There are little definite historical records concerning the shroud prior to the 14th century. Although there are numerous reports of Jesus' burial shroud, or an image of his head, of unknown origin, being venerated in various locations before the 14th century, there is little but reliable historical evidence that these refer to the shroud currently at Turin Cathedral.[5] A burial cloth, which some historians maintain was the Shroud, was owned by the Byzantine emperors but disappeared during the Sack of Constantinople in 1204.[6]

Barbara Frale has cited that the Order of Knights Templar were in the possession of a relic showing a red, monochromatic image of a bearded man on linen or cotton.[7] Historical records seem to indicate that a shroud bearing an image of a crucified man existed in the possession of Geoffroy de Charny in the small town of Lirey, France around the years 1353 to 1357.[1] However, the correspondence of this shroud with the shroud in Turin, and its very origin has been debated by scholars and lay authors, with claims of forgery attributed to artists born a century apart.

Some contend that the Lirey shroud was the work of a confessed forger and murderer.[8] Professor Nicholas Allen of South Africa on the other hand believes that the image was made photographically and not by an artist. Professor John Jackson of the Turin Shroud Centre of Colorado argues that the shroud in Turin dates back to the 1st century AD.[9]

The history of the shroud from the 15th century is well recorded. In 1532, the shroud suffered damage from a fire in the chapel where it was stored. A drop of molten silver from the reliquary produced a symmetrically placed mark through the layers of the folded cloth. Poor Clare Nuns attempted to repair this damage with patches. In 1578 the House of Savoy took the shroud to Turin and it has remained at Turin Cathedral ever since.[10]

Repairs were made to the shroud in 1694 by Sebastian Valfrè to improve the repairs of the Poor Clare nuns.[11] Further repairs were made in 1868 by Clotilde of Savoy.[12] The shroud remained the property of the House of Savoy until 1983, when it was given to the Holy See, the rule of the House of Savoy having ended in 1946.

A fire, possibly caused by arson, threatened the shroud on 11 April 1997.[13] In 2002, the Holy See had the shroud restored. The cloth backing and thirty patches were removed, making it possible to photograph and scan the reverse side of the cloth, which had been hidden from view for centuries. The Shroud was exhibited to the public from August 8 to August 12, 2018.

Prior to the 14th century

The Gospel of the Hebrews, a 2nd-century manuscript extant in about 20 lines states 'and after He had given the linen cloth to the servant of the priest he appeared to James'

Although there are numerous reports of Jesus' burial shroud, or an image of his head, of unknown origin, being venerated in various locations before the fourteenth century, there is no historical evidence that these refer to the shroud currently at Turin Cathedral.[5]

The Gospel of John states that: "Then cometh Simon Peter following him, and went into the sepulchre, and seeth the linen clothes [othonia] lie, and the napkin [soudarion], that was about his head, not lying with the linen clothes, but wrapped together in a place by itself" (John 20:6–7, KJV). The Gospels of Matthew (27:59), Mark (15:46), and Luke (23:53) all refer to a singular "sindon" (fine linen cloth) which was wrapped (entulisso) around Jesus' body. In other Greek usage the word "sindon" refers to a wrapping such as a toga (Mark 14:51-52) or a mummy wrapping (Herodotus 2, 86).

The Image of Edessa was reported to contain the image of the face of Jesus, and its existence is reported since the sixth century. Some have suggested a connection between the Shroud of Turin and the Image of Edessa.[14] No legend connected with that image suggests that it contained the image of a beaten and bloody Jesus. It was said to be an image transferred by Jesus to the cloth in life. This image is generally described as depicting only the face of Jesus, not the entire body. Proponents of the theory that the Edessa image was actually the shroud, led by Ian Wilson, theorize that it was always folded in such a way as to show only the face, as recorded in the apocryphical Acts of Thaddeus from around that time, which say it was tradiplon- folded into 4 pieces.[15]

Ian Wilson, under 'Reconstructed Chronology of the Turin Shroud'[16] recounts that the 'Doctrine of Addai' mentions a 'mysterious portrait' in connection with the healing of Abgar V. A similar story is recorded in Eusebius' History of the Church bk 1, ch 13,[17] which does not mention the portrait.

Three principal pieces of evidence are cited in favor of the identification with the shroud. Saint John of Damascus mentions the image in his anti-iconoclastic work On Holy Images,[18] describing the Edessa image as being a "strip", or oblong cloth, rather than a square, as other accounts of the Edessa cloth hold. However, in his description, St. John still speaks of the image of Jesus' face when he was alive.

In several articles, Daniel Scavone, professor Emeritus of history at the University of southern Indiana, puts forward a hypothesis which identifies the Shroud of Turin as the real object that inspires the romances of the Holy Grail.[19]

To the contrary, Averil Cameron, expert of Late Antique and Byzantine History at the University of Oxford, denies the possibility of the Turin shroud being identified with the Image of Edessa. Among the reasons are too big differences in the historical descriptions of the Image of Edessa compared to the shroud.[20] The Image of Edessa has according to her its origin in the resistance to the Byzantine iconoclasm.[21]

On the occasion of the transfer of the cloth to Constantinople in 944, Gregory Referendarius, archdeacon of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, preached a sermon about the artifact. This sermon had been lost but was rediscovered in the Vatican Archives and translated by Mark Guscin [22] in 2004. This sermon says that this Edessa cloth contained not only the face, but a full-length image, which was believed to be of Jesus. The sermon also mentions bloodstains from a wound in the side. Other documents have since been found in the Vatican library and the University of Leiden, Netherlands, confirming this impression. "Non tantum faciei figuram sed totius corporis figuram cernere poteris" (You can see not only the figure of a face, but [also] the figure of the whole body). (In Italian) (Cf. Codex Vossianus Latinus Q69 and Vatican Library Codex 5696, p. 35.)

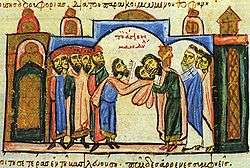

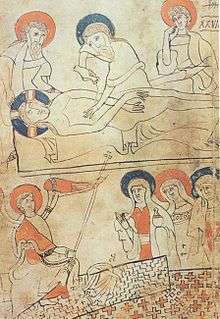

An illustration of what appears to some to be the Shroud of Turin complete with the distinctive "L-shaped" burn marks and what is interpreted by some to be fishbone weave is depicted in Codex Pray, an Illuminated manuscript written in Budapest, Hungary between 1192 and 1195.[23][24]

In the Budapest National Library is the Pray Manuscript, the oldest surviving text of the Hungarian language. It was written between 1192 and 1195 (65 years before the earliest carbon-14 date in the 1988 tests). One of its illustrations shows preparations for the burial of Christ. The picture supposedly includes a burial cloth in the post-resurrection scene. According to proponents, it has the same herringbone weave as the Shroud, plus four holes near one of the edges. The holes form an "L" shape. Proponents claim this odd pattern of holes is the same as the ones found on the Shroud of Turin. They are burn holes, perhaps from a hot poker or incense embers.[25] On the other hand, Italian Shroud researcher Gian Marco Rinaldi interprets the item that is sometimes identified as the Shroud as a probable rectangular tombstone as seen on other sacred images, alleged holes as decorative elements, as seen, for example, on the angel's wing and clothes. Rinaldi also points out that the alleged shroud in the Pray codex does not contain any image.[26] Furthermore, it would be most unlikely that anyone who had seen the Shroud would have shown Christ being buried without any sign of the wounds that are so graphically shown on the Shroud.

In 1204, a knight named Robert de Clari who participated in the Fourth Crusade that captured Constantinople, claims the cloth was among the countless relics in the city: "Where there was the Shroud in which our Lord had been wrapped, which every Friday raised itself upright so one could see the figure of our Lord on it. And none knows - neither Greek nor Frank - what became of that shroud when the city was taken."[27] (The apparent miracle of the cloth raising itself may be accounted for as a mistranslation: the French impersonal passive takes the form of a reflexive verb. Thus the original French could equally well be translated as the cloth was raised upright. De Clari's matter of fact delivery does not suggest that he witnessed anything out of the ordinary.) However, the historians Madden and Queller describe this part of Robert's account as a mistake: Robert had actually seen or heard of the sudarium, the handkerchief of Saint Veronica (which also purportedly contained the image of Jesus), and confused it with the grave cloth (sindon).[28] In 1205, the following letter was allegedly sent by Theodore Angelos, a brother of Michael I Komnenos Doukas, to Pope Innocent III protesting the attack on the capital. From the document, dated 1 August 1205 in Rome: "The Venetians partitioned the treasures of gold, silver, and ivory while the French did the same with the relics of the saints and the most sacred of all, the linen in which our Lord Jesus Christ was wrapped after his death and before the resurrection. We know that the sacred objects are preserved by their predators in Venice, in France, and in other places, the sacred linen in Athens." (Codex Chartularium Culisanense, fol. CXXVI (copia), Bilioteca del Santuario di Montevergine)[29] According to Emmanuel Poulle, a French medievalist, although the Mandylion is not the Shroud of Turin, the texts "attest the presence of the Shroud in Constantinople before 1204".[6] But it was claimed that the letter of Theodore and other documents contained in the Chartularium are a modern forgery.[30]

Unless it is the Shroud of Turin, then the location of the Image of Edessa since the 13th century is unknown but may well have been among the relics sold to Louis IX and housed in the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris until lost in the French Revolution.

Some authors suggest that the shroud was captured by the knight Otto de la Roche who became Duke of Athens, sometimes adding that he soon relinquished it to the Knights Templar. It was subsequently taken to France, where the first known keeper of the Turin Shroud had links both to the Templars as well the descendants of Otto. Some speculate that the shroud could have been a major part of the famed "Templar treasure" that treasure hunters still seek today.

The association with the Templars seems to be based on a coincidence of family names; the Templars were a celibate order and so unlikely to have children after entering the Order.

14th and 15th centuries

The fullest academic account of the history of the Shroud since its first appearance in 1355 is John Beldon-Scott, Architecture for the Shroud: Relic and Ritual in Turin, University of Chicago Press, 2003. This study is indispensable for its many illustrations that show features of the Shroud images now lost.

The 14th century attribution of the origin of the shroud refers to a shroud in Lirey, France dating to 1353–1357. It is related that the widow of the French knight Geoffroi de Charny had it displayed in a church at Lirey, France (diocese of Troyes). According to the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia:

On 20 June 1353, Geoffroy de Charny, Lord of Savoisy and Lirey, founded at Lirey in honour of the Annunciation a collegiate church with six canonries, and in this church he exposed for veneration the Holy Winding Sheet. Opposition arose on the part of the Bishop of Troyes, who declared after due inquiry that the relic was nothing but a painting, and opposed its exposition. Clement VI by four Bulls, 6 Jan., 1390, approved the exposition as lawful. In 1418 during the civil wars, the canons entrusted the Winding Sheet to Humbert, Count de La Roche, Lord of Lirey. Margaret, widow of Humbert, never returned it but gave it in 1452 to the Duke of Savoy. The requests of the canons of Lirey were unavailing, and the Lirey Winding Sheet is the same that is now exposed and honoured at Turin."[31]

In the Museum Cluny in Paris, the coats of arms of this knight and his widow can be seen on a pilgrim medallion, which also shows an image of the Shroud of Turin.

During the fourteenth century, the shroud was often publicly exposed, though not continuously, because the bishop of Troyes, Henri de Poitiers, had prohibited veneration of the image. Thirty-two years after this pronouncement, the image was displayed again, and King Charles VI of France ordered its removal to Troyes, citing the impropriety of the image. The sheriffs were unable to carry out the order.

In 1389, the image was denounced as a fraud by Bishop Pierre D'Arcis in a letter to the Avignon Antipope Clement VII, mentioning that the image had previously been denounced by his predecessor Henri de Poitiers, who had been concerned that no such image was mentioned in scripture. Bishop D'Arcis continued, "Eventually, after diligent inquiry and examination, he discovered how the said cloth had been cunningly painted, the truth being attested by the artist who had painted it, to wit, that it was a work of human skill and not miraculously wrought or bestowed." (In German:.[32]) The artist is not named in the letter.[33][34]

The letter of Bishop D'Arcis also mentions Bishop Henri's attempt to suppress veneration but notes that the cloth was quickly hidden "for 35 years or so", thus agreeing with the historical details already established above. The letter provides an accurate description of the cloth: "upon which by a clever sleight of hand was depicted the twofold image of one man, that is to say, the back and the front, he falsely declaring and pretending that this was the actual shroud in which our Saviour Jesus Christ was enfolded in the tomb, and upon which the whole likeness of the Saviour had remained thus impressed together with the wounds which He bore."

Despite the pronouncement of Bishop D'Arcis, Antipope Clement VII (first antipope of the Western Schism) did not revoke the permission given earlier to the church of Lirey to display the object,[35] but instructed its clergy that it should not be treated as a relic[36] and should not be presented to the public as the actual shroud of Christ, but as an image or representation of it.[37] He prescribed indulgences for the many pilgrims who came to the church out of devotion for "even a representation of this kind",[38] so that veneration continued.[39]

In 1418, Humbert of Villersexel, Count de la Roche, Lord of Saint-Hippolyte-sur-Doubs, moved the shroud to his castle at Montfort, Doubs, to provide protection against criminal bands, after he married Charny's granddaughter Margaret. It was later moved to Saint-Hippolyte-sur-Doubs. After Humbert's death, canons of Lirey fought through the courts to force the widow to return the cloth, but the parliament of Dole and the Court of Besançon left it to the widow, who traveled with the shroud to various expositions, notably in Liège and Geneva.

The widow sold the shroud in exchange for a castle in Varambon, France in 1453. The new owner, Anne of Cyprus, Duchess of Savoy, stored it in the Savoyard capital of Chambéry in the newly built Saint-Chapelle, which Pope Paul II shortly thereafter raised to the dignity of a collegiate church. In 1464, Anne's husband, Louis, Duke of Savoy agreed to pay an annual fee to the Lirey canons in exchange for their dropping claims of ownership of the cloth. Beginning in 1471, the shroud was moved between many cities of Europe, being housed briefly in Vercelli, Turin, Ivrea, Susa, Chambéry, Avigliana, Rivoli, and Pinerolo. A description of the cloth by two sacristans of the Sainte-Chapelle from around this time noted that it was stored in a reliquary: "enveloped in a red silk drape, and kept in a case covered with crimson velours, decorated with silver-gilt nails, and locked with a golden key."

In 1543 John Calvin, in his Treatise on Relics, wrote of the Shroud, which was then at Nice, "How is it possible that those sacred historians, who carefully related all the miracles that took place at Christ’s death, should have omitted to mention one so remarkable as the likeness of the body of our Lord remaining on its wrapping sheet?" He also noted that, according to St. John, there was one sheet covering Jesus's body, and a separate cloth covering his head. He then stated that "either St. John is a liar," or else anyone who promotes such a shroud is "convicted of falsehood and deceit".[40]

16th century to present

The history of the shroud from the middle of the 16th century is well recorded. The existence of a miniature by Giulio Clovio, which gives a good representation of what was seen upon the shroud about the year 1540, confirms that the shroud housed in Turin today is the same one as in the middle of the 16th century.[42] In 1578 the House of Savoy took the shroud to Turin and it has remained at Turin Cathedral ever since.[43]

In 1532, the shroud suffered damage from a fire in the chapel where it was stored. A drop of molten silver from the reliquary produced a symmetrically placed mark through the layers of the folded cloth. Poor Clare Nuns attempted to repair this damage with patches. Some have suggested that there was also water damage from the extinguishing of the fire. However, there is some evidence that the watermarks were made by condensation in the bottom of a burial jar in which the folded shroud may have been kept at some point. In 1578, the shroud arrived again at its current location in Turin. It was the property of the House of Savoy until 1983, when it was given to the Holy See, the rule of the House of Savoy having ended in 1946.

In 1988, the Holy See agreed to a radiocarbon dating of the relic, for which a small piece from a corner of the shroud was removed, divided, and sent to laboratories. (More on the testing is seen below.) Another fire, possibly caused by arson, threatened the shroud on 11 April 1997, but fireman Mario Trematore was able to remove it from its heavily protected display case and prevent further damage. In 2002, the Holy See had the shroud restored. The cloth backing and thirty patches were removed. This made it possible to photograph and scan the reverse side of the cloth, which had been hidden from view. Using sophisticated mathematical and optical techniques, a ghostly part-image of the body was found on the back of the shroud in 2004. Italian scientists had exposed the faint imprint of the face and hands of the figure. The Shroud was publicly exhibited in 2000 for the Great Jubilee, and in 2010 with the approval of Pope Benedict XVI, and in 2015 with the approval of Pope Francis. Another exhibition is scheduled for 2025.

Detailed comments on this operation were published by various Shroud researchers.[44] In 2003, the principal restorer Mechthild Flury-Lemberg, a textile expert from Switzerland, published a book with the title Sindone 2002: L'intervento conservativo — Preservation — Konservierung (ISBN 88-88441-08-5). She describes the operation and the reasons it was believed necessary. In 2005, William Meacham, an archaeologist who has studied the Shroud since 1981, published the book The Rape of the Turin Shroud (ISBN 1-4116-5769-1) which is fiercely critical of the operation. He rejects the reasons provided by Flury-Lemberg and describes in detail what he calls "a disaster for the scientific study of the relic".

Historical attributions

Christian iconography

Art historian W.S.A. Dale proposed that the Shroud was an icon created for liturgical use, and suggested an 11th-century date based on art-historical grounds.[45]

Analysis of proportion

The man on the image is taller than the average first-century resident of Judaea and the right hand has longer fingers than the left, along with a significant increase of length in the right forearm compared to the left.[46]

Analysis of optical perspective

Further evidence for the Shroud as an art object comes from what might be called the "Mercator projection" argument. The shroud in two dimensions presents a three-dimensional image projected onto a planar (two-dimensional) surface, just as in a photograph or painting. This perspective is consistent with both painting and with image formation using a bas relief.[45]

Variegated images

Banding on the Shroud is background noise, which causes us to see the gaunt face, long nose, deep eyes, and straight hair. These features are caused by dark vertical and horizontal bands that go across the eyes. Using enhancement software (Fast Fourier Transform filters), the effect of these bands can be minimized. The result is a more detailed image of the shroud.[47]

Burial posture

The burial posture of the shroud, with hands crossed over the pelvis, was used by Essenes (2nd century BC to the 1st century AD), but was also found in a burial site under a medieval church with skeletons which were dated pre-1390 and post Roman.[48][49]

Leonardo da Vinci

In June 2009, the British television station Channel 5 aired a documentary that claimed the shroud was forged by Leonardo da Vinci.[50]

Recently a study stated that the shroud of Turin had been faked by Leonardo da Vinci.[50] According to the study, the Renaissance artist created the artifact by using pioneering photographic techniques and a sculpture of his own head, and suggests that the image on the relic is Leonardo's face which could have been projected onto the cloth, The Daily Telegraph reported.[50]

History Today article

In an article published by History Today in November 2014, British scholar Charles Freeman analyses early depictions and descriptions of the Shroud and argues that the iconography of the bloodstains and all-over scourge marks are not known before 1300 and the Shroud was a painted linen at that date, with the paint having disintegrated leaving a discoloured linen image underneath. He also argues that the dimensions and format of the weave are typical of a medieval treadle loom. As it was unlikely that a forger would have deceived anyone with a single cloth with images on it, Freeman seeks an alternative function. He goes on to argue that the Shroud was a medieval prop used in Easter ritual plays depicting the resurrection of Christ. He believes it was used in a ceremony called the 'Quem Quaeritis?' or 'whom do you seek?' which involved re-enacting gospel accounts of the resurrection, and is represented as such in the well-known Lirey pilgrim badge. As such it was deservedly an object of veneration from the fourteenth century as it is still is today.[51]

See also

References

- William Meacham, The Authentication of the Turin Shroud, An Issue in Archeological Epistemogy, Current Anthropology, 24, 3, 1983 Article

- BBC article 31 January 2005

- Emmanuel Poulle, ″Les sources de l'histoire du linceul de Turin. Revue critique″, Revue d'Histoire Ecclésiastique, 2009/3-4, p. 776.Abstract Archived 2011-07-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Architecture for the shroud: relic and ritual in Turin by John Beldon Scott 2003 ISBN 0-226-74316-0 page xxi

- Humber, Thomas: The Sacred Shroud. New York: Pocket Books, 1980. ISBN 0-671-41889-0

- Emmanuel Poulle, ″Les sources de l'histoire du linceul de Turin. Revue critique″, Revue d'Histoire Ecclésiastique, 2009/3-4, pp. 747-781.Abstract Archived 2011-07-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Barbara Frale, The Templars and The Shroud of Christ, page 99 (Maverick House, 2011; ISBN 1-905379-73-0), Frale citing Charles Du Fresne, Glossarium Mediae et Infimae Latinitatis, page 447 (Graz: Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt, 1954).

- Mercer dictionary of the Bible by Watson E. Mills, Roger Aubrey Bullard 1998 ISBN 0-86554-373-9 page 822

- BBC News March 21, 2008 Shroud mystery refuses to go away

- The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia:Q-Z by Geoffrey W. Bromiley 1995 ISBN 0-8028-3784-0 page 495

- Architecture for the shroud: relic and ritual in Turin by John Beldon Scott 2003 ISBN 0-226-74316-0 page 26

- Holy Shroud of Turin by Arthur Stapylton Barnes 2003 ISBN 0-7661-3425-3 page 62

- NY Times April 12, 1997 Shroud of Turin Saved From Fire in Cathedral

- Wilson, pp. 148-175

- Andrzej Datko: The Book of Relics; chapter: The Shroud of Turin, p.351. Cracow, 2014

- p287 Ian Wilson, 1978, The Turin Shroud, Penguin Books (1979) first published by Doubleday & Company Inc., (1978) Under the title The Shroud of Turin

- Trans. G A Williamson, Ed Andrew Louth, Eusebius, The History of the Church, Penguin Books

- "St. John of Damascene on Holy Images (Followed by Three Sermons on the Assumption) | Christian Classics Ethereal Library". Ccel.org. Retrieved 2009-04-12.

- D. Scavone: "Joseph of Arimathea, the Holy Grail, and the Edessa Icon," Arthuriana vol. 9, no. 4, 3-31 (Winter 1999) (Article and abstract) ;Scavone, “British King Lucius, the Grail, and Joseph of Arimathea: The Question of Byzantine Origins.”, Publications of the Medieval Association of the Midwest 10 (2003): 101-42, vol. 10, 101-142 (2003).

- Averil Cameron, The Sceptic and the Shroud London: King's College Inaugural Lecture monograph (1980)

- Averil Cameron, The mandylion and Byzantine Iconoclasm. in H. Kessler, G. Wolf, eds, The holy face and the paradox of representation. Bologna, (1998), 33-54

- "THE SERMON OF GREGORY REFERENDARIUS" (PDF).

- Wilson, Ian.(1986)The Mysterious Shroud, Garden city, New York; Doubleday & Company. p.115

- Bercovits, I. (1969) Dublin: Irish University Press. Illuminated Manuscripts in Hungary

- Wilson, I., "The Evidence of the Shroud", Guild Publishing: London, 1986, p.114 and http://www.newgeology.us/presentation24.html

- G.M.Rinaldi, "Il Codice Pray", http://sindone.weebly.com/pray.html

- Robert de Clari, The History Of Them That Took Constantinople, chapter 92 , in Edward N. Stone, Three Old French Chronicles of the Crusades (University of Washington Publications in the Social Sciences, volume 10; 1939).

- Madden, Thomas, and Donald Queller. The Fourth Crusade: The Conquest of Constantinople. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1997. Second edition. page 139.

- "The letter was rediscovered in the archive of the Abbey of St. Caterina a Formiello, Naples; it was folio CXXVI of the Chartularium Culisanense, now destroyed, a copy of which came to the Naples as a result of close political ties with the imperial Angelus-Comnenus family from 1481 on. The Greek original had been lost." in: "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-10-08. Retrieved 2010-03-20.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link); see also: a photo of the document Archived 2012-02-11 at the Wayback Machine

- A. Nicolotti, "Su alcune testimonianze del Chartularium Culisanense, sulle false origini dell'Ordine Costantiniano Angelico di Santa Sofia e su taluni suoi documenti conservati presso l'Archivio di Stato di Napoli"., in «Giornale di storia» 8 (2012).

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- "Das Turiner Grabtuch". Archived from the original on 2009-03-18. Retrieved 2010-03-20.

- English translation of Memorandum contained in Ian Wilson, The Turin Shroud, p. 230-235 (Victor Gollancz Ltd; 1978 ISBN 0-575-02483-6)

- Joe Nickell, Inquest on the Shroud of Turin: Latest Scientific Findings, Prometheus Books, 1998, ISBN 978-1-57392-272-2

- Emmanuel Poulle, "Le linceul de Turin victime d'Ulysse Chevalier [The Turin shroud victim of Ulysse Chevalier]", Revue d'Histoire de l'Eglise de France, t. 92, 2006, 343-358. Abstract (in french only).

- Cf. U. Chevalier (1903), Autour des origines du suaire de Lirey. Avec documents inédits (Bibliothèque liturgique, vol. 5) (Paris: Picard), p. 35 (letter J): "...nec alias solempnitates faciant que fieri solent in reliquiis ostendendis..." This stipulation was maintained in the final version of the letter (Reg. Avign. n° 261, folio 259), as cited in Pierre de Riedmatten (2008), Ulysse Chevalier pris en flagrant délit... (Retrieved from http://suaire-turin.fr/?page_id=176 Archived 2016-05-06 at the Wayback Machine)

- Cf. U. Chevalier (1903), Autour des origines du suaire de Lirey. Avec documents inédits (Bibliothèque liturgique, vol. 5) (Paris: Picard), p. 37 (letter K): "...quod figuram seu representationem predictam non ostendunt ut verum sudarium ... sed tanquam figuram seu representationem dicti sudarii". Also cited in Pierre de Riedmatten (2008), Ulysse Chevalier pris en flagrant délit... (Retrieved from http://suaire-turin.fr/?page_id=176 Archived 2016-05-06 at the Wayback Machine)

- "Cum ... ad ecclesiam ... causa devocionis eciam representacionis hujusmodi confluat non modica populi multitudo..." (U. Chevalier (1903), Autour des origines du suaire de Lirey. Avec documents inédits (Bibliothèque liturgique, vol. 5) (Paris: Picard), p. 38 (letter K)).

- Scandals and Follies of the 'Holy Shroud' | Skeptical Inquirer | Find Articles at BNET.com

- John Calvin, 1543, Treatise on Relics, trans. by Count Valerian Krasinski, 1854; 2nd ed. Edinburgh: John Stone, Hunter, and Company, 1870; reprinted with an introduction by Joe Nickell, Amherst, N.Y.: Prometheus Books, 2009.

- The Shroud of Christ by Paul Vignon, Paul Tice 2002 ISBN 1-885395-96-5 page 21

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- How and why the shroud was transferred to Turin was studied by Filiberto Pingone, historian of the House of Savoy, who wrote the very first book on the Linen. See Filiberto Pingone, La Sindone dei Vangeli (Sindon Evangelica). Componimenti poetici sulla Sindone. Bolla di papa Giulio II (1506). Pellegrinaggio di S. Carlo Borromeo a Torino (1578). Introduzione, traduzione, note e riproduzione del testo originale a cura di Riccardo Quaglia, nuova edizione riveduta (2015), Biella 2015, pp. 260, ISBN 978-1-4452-8258-9.

- "shroud.com". shroud.com. Retrieved 2009-04-12.

- Dale, W.S.A. (1987). "The Shroud of Turin: Relic or Icon?". Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research B. 29: 187–192. doi:10.1016/0168-583X(87)90233-3.

- Angier, Natalie. 1982. Unraveling the Shroud of Turin. The image of the man from the front is taller than the image of his back. Discover Magazine, October, pp. 54-60.

- "The double superficiality of the frontal image of the Turin Shroud", Giulio Fanti and Roberto Maggiolo, Journal of Optics A: Pure and Applied Optics, June 2004

- https://doncasterarchaeology.co.uk/Documents/The%20Corn%20Exchange.doc%5B%5D as of 25 July 2008

- as of 25 July 2008 - showing Roman rule ended before then Archived 15 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Jamieson, Alastair (1 July 2009). "Was Turin Shroud faked by Leonardo da Vinci?". London: telegraph. Retrieved 2009-07-03.

- https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/oct/23/turin-shroud-jesus-christ-medieval-easter-ritual-historian-charles-freeman