History of American comics

The history of American comics began in the 19th century in mass print media, in the era of yellow journalism, where newspaper comics served as a boon to mass readership.[1] In the 20th century, comics became an autonomous art medium[1] and an integral part of American culture.[2]

Overview

The history of American comics started in 1842 with the U.S. publication of Rodolphe Töpffer's work The Adventures of Mr. Obadiah Oldbuck,[3][4] but the medium was initially developed through comic strips in daily newspapers. The seminal years of comic strips established its canonical features (e.g., speech balloons) and initial genres (family strips, adventure tales). Comic-strip characters became national celebrities, and were subject to cross-media adaptation, while newspapers competed for the most popular artists.

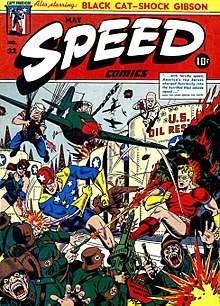

The true comic book, published independently of a newspaper, appeared in 1934. Although the first comic books were themselves newspaper-strip reprints, comics soon featured original material, and the first appearance of Superman launched the Golden Age of Comic Books. During World War II, superheroes and funny animals were the most popular genres, but new genres were also developed (i.e., western, romance, and science fiction) and increased readership. Comic book sales began to decline in the early 1950s, and comics were socially condemned for their alleged harmful effects on children; to protect the reputation of comic books, the Comics Code Authority (CCA) was formed, but this eliminated the publication of crime and horror genres.

The Silver Age of Comic Books began in 1956 with a resurgence of interest in superheroes. Non-superhero sales declined and many publishers closed. Marvel Comics introduced new and popular superheroes and thereby became the leading comics publisher in the Bronze Age of Comic Books (from the early 1970s to 1985). Unlike the Golden and Silver ages, the start of the Bronze Age is not marked by a single event. Although the Bronze Age was dominated by the superhero genres, underground comics appeared for the first time, which addressed new aesthetic themes and followed a new distribution model.

Following the Bronze Age, the Modern Age initially seemed to be a new golden age. Writers and artists redefined classic characters and launched new series that brought readership to levels not seen in decades, and landmark publications such as Maus redefined the medium's potential. The industry, however, soon experienced a series of financial shocks and crises that threatened its viability, and from which it took years to recover.

Periodization schemes

American comics historians generally divide 20th-century American comics history chronologically into ages. The first period, called Golden Age, extends from 1938 (first appearance of Superman in Action Comics #1 by National Allied Publications, a corporate predecessor of DC Comics) to 1954 (introduction of the Comics Code). The following period, the Silver Age, goes from 1956 to early 1970s. The Bronze Age follows immediately and spans until c. 1986. Finally the last period, from 1986 until today, is the Modern Age.[5] This division is standard but not all the critics apply it, since some of them propose their own periods.[5][6] Furthermore, the dates selected may vary depending on the authors; there are at least four dates to mark the end of the Bronze Age.

An alternative name for the period after the mid-1980s is Dark Age of Comic Books, due to the popularity and artistic influence of titles with serious content, such as Batman: The Dark Knight Returns and Watchmen.[7] Pop culture writer Matthew J. Theriault proposed an alternative periodization scheme in which the recent history of comics is divided in ages: dark (Dark Age, from c. 1985 to 2004), modern (Modern Age, from c. 2004 to 2011; the era began with the publication of "Avengers Disassembled" and "Infinite Crisis"), and postmodern (Postmodern Age, since 2011; the era began with the publication of Ultimate Fallout #4, the first appearance of Miles Morales).[8] Comics creator Tom Pinchuk proposed the name Diamond Age for the period starting with the appearance of Marvel's Ultimate line (2000–present).[9]

Originally only the Golden Age and the Silver Age had a right of citizenship since the terms "Golden Age" and "Silver Age" had appeared in a letter from a reader published in the nº 42 of Justice League of America in February 1966 that stated: "If you guys keep bringing back the heroes from the Golden Age, people 20 years from now will be calling this decade the Silver Sixties!"[10]

Victorian Age (1842–1897)

Comics in the United States originated in the early European works. In fact, in 1842, the work Les amours de Mr. Vieux Bois by Rodolphe Töpffer was published under the title The Adventures of Mr. Obadiah Oldbuck in the U.S.[3][4] This edition (a newspaper supplement titled Brother Jonathan Extra No. IX, September 14, 1842)[11][12] is an unlicensed copy of the original work as it was done without Töpffer's authorization. This first publication was followed by other works of this author, always under types of unlicensed editions.[13] Töpffer comics were reprinted regularly until the late 1870s,[14] which gave American artists the idea to produce similar works. In 1849, Journey to the Gold Diggins by Jeremiah Saddlebags by James A. and Donald F. Read was the first American comic.[15][16]

Domestic production remained limited until the emergence of satirical magazines that, on the model of British Punch, published drawings and humorous short stories, but also stories in pictures[14] and silent comics. The three main titles were Puck, Judge and Life.[17] Authors such as Arthur Burdett Frost created stories as innovative as those produced in the same period by Europeans. However, these magazines only reach an audience educated and rich enough to afford them. Just the arrival of technological progress allowed easy and cheap reproduction of images for the American comic to take off. Some media moguls like William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer engaged in a fierce competition to attract readers and decided to publish cartoons in their newspapers.[18]

Platinum Age (1897–1938)

The period of the late 19th century (the so-called "Platinum Age") was characterized by a gradual introduction of the key elements of the American mass comics. Then, the funnies were found in the humor pages of newspapers: they were published in the Sunday edition to retain readership. Indeed, it was not the information given that distinguished the newspapers but the editorials and the pages which were not informative, whose illustrations were an important component.[19] These pages were then called comic supplement. In 1892, William Randolph Hearst published cartoons in his first newspaper, The San Francisco Examiner. James Swinnerton created on this occasion the first drawings of humanized animals in the series Little Bears and Tykes.[20] Nevertheless, drawings published in the press were rather a series of humorous independent cartoons occupying a full page. The purpose of the cartoon itself, as expressed through narrative sequence expressed through images which follow one another, was only imposed slowly.

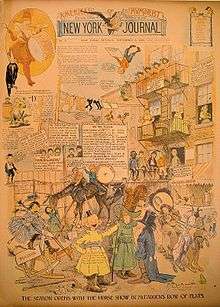

In 1894, Joseph Pulitzer published in the New York World the first color strip, designed by Walt McDougall, showing that the technique already enabled this kind of publications.[21] Authors began to create recurring characters. Thus, in 1894 and still in the New York World, Richard F. Outcault presented Hogan's Alley, created shortly before in the magazine Truth Magazine. In this series of full-page large drawings teeming with humorous details, he staged street urchins, one of whom was wearing a blue nightgown (which turned yellow in 1895). Soon, the little character became the darling of readers who called him Yellow Kid.[22] On October 25, 1896, the Yellow Kid pronounced his first words in a speech balloon (they were previously written on his shirt). Outcault had already used this method but this date is often considered as the birth of comics in the United States.[23]

Yellow Kid success boosted sales of the New York World, fueling the greed of Hearst. Fierce competition between Hearst and Pulitzer in 1896 led to enticing away of Outcault by Hearst to work in the New York Journal. A bitter legal battle allowed Pulitzer to keep publishing Hogan's Alley (which he entrusted to Georges B. Luks) and Hearst to publish the series under another name. Richard Outcault chose the title The Yellow Kid. Published in 1897, the Yellow Kid magazine consisting of sheets previously appeared in newspapers and it was the first magazine of its kind.[24][25]

From 1903 to 1905 Gustave Verbeek, wrote his comic series "The UpsideDowns of Old Man Muffaroo and Little Lady Lovekins" between 1903 and 1905. These comics were made in such a way that one could read the 6 panel comic, flip the book and keep reading. He made 64 such comics in total.

Golden Age (1938–1956)

Silver Age (1956–1970)

The Silver Age began with the publication of DC Comics' Showcase #4 (Oct. 1956), which introduced the modern version of the Flash.[26][27][28] At the time, only three superheroes—Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman—were still published under their own titles.[29]

Bronze Age (1970–1986)

Modern Age (1986–present)

See also

References

- Williams, Paul and James Lyons (eds.), The Rise of the American Comics Artist: Creators and Contexts, University Press of Mississippi, 2010, p. 106.

- Waugh, Coulton, The Comics, University Press of Mississippi, 1991, p. xiii.

- (Duncan & Smith 2009, p. 25)

- Jamie Coville, "History of Comics: Platinum Age" – TheComicBooks.com.

- (Rhoades 2008, p. 4)

- (Duncan & Smith 2009, p. 22)

- Voger, Mark (2006). The Dark Age: Grim, Great & Gimmicky Post-Modern Comics. TwoMorrows Publishing. p. 6. ISBN 1-893905-53-5.

- Matthew J. Theriault, "We're Living in the Postmodern Age of Comics", The Hub City Review, March 10, 2016: "Starting with Miles, a character of mixed Black and Hispanic descent, the new and redesigned characters of the Postmodern Age are almost universally representatives of previously marginalized demographics."

- Tom Pinchuk, "Is this the "Diamond Age" of Comics?", Comic Vine, May 25, 2010.

- (Rhoades 2008, p. 71)

- The Adventures of Mr. Obadiah Oldbuck at Don Markstein's Toonopedia. Archived from the original on March 13, 2012. "On September 14, 1842, a New York paper, Brother Jonathan, ran an English-language version of Oldbuck (published in Britain a year earlier) as a supplement."

- "Brother Jonathan Extra #v2#9". Grand Comics Database.

- (Rubis 2012, p. 39)

- Coville, Jamie (2001). "See you in the Funny Pages..." The Comic Books. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- (Rhoades 2008, p. 3)

- (Gabilliet 2010, p. 4)

- (Harvey 1994, p. 4)

- (Rubis 2012, p. 45)

- (Harvey 2009, p. 38)

- (Baron-Carvais 1994, p. 12)

- (Dupuis 2005, p. 16)

- (Baron-Carvais 1994, p. 13)

- Lord, Denis (March 2004). "Bandes dessinées: le phylactère francophone célèbre ses 100 ans". Le Devoir (in French). Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- (Duncan & Smith 2009, p. 26)

- The Yellow kid. Library of Congress.

- Shutt, Craig (2003). Baby Boomer Comics: The Wild, Wacky, Wonderful Comic Books of the 1960s!. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. p. 20. ISBN 0-87349-668-X.

The Silver Age started with Showcase #4, the Flash's first appearance.

- Sassiene, Paul (August 1994). The Comic Book: The One Essential Guide for Comic Book Fans Everywhere. Edison, New Jersey: Chartwell Books, a division of Book Sales. p. 69. ISBN 978-1555219994.

DC's Showcase No. 4 was the comic that started the Silver Age

- "DC Flashback: The Flash". Comic Book Resources. July 2, 2007. Archived from the original on January 12, 2009. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- Jacobs, Will; Gerard Jones (1985). The Comic Book Heroes: From the Silver Age to the Present. New York, New York: Crown Publishing Group. p. 34. ISBN 0-517-55440-2.

- Attribution

- This article is based on the article from the French Wikipedia "Histoire de la bande dessinée américaine".

Bibliography

- Baron-Carvais, Annie (1994). La Bande dessinée (in French) (4th ed.). Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. p. 127. ISBN 978-2130437628. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- Booker, M. Keith, ed. (2010). Encyclopedia of Comic Books and Graphic Novels. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-Clio. p. 763. ISBN 978-0-313-35746-6. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- Cooke, Jon B.; Roach, David, eds. (2001). Warren Companion: The Ultimate Reference Guide. TwoMorrows Publishing. p. 272. ISBN 9781893905085. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- Courtial, Gérard; Faur, Jean-Claude (1985). À la rencontre des super-héros (in French). Marseille: Bédésup. p. 152. OCLC 420605740.

- DiPaolo, Marc (2011). War, Politics and Superheroes. Ethics and Propaganda in Comics and Film. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. p. 330. ISBN 9780786447183. OCLC 689522306.

- Duncan, Randy; Smith, Matthew J. (2009). The Power of Comics: History, Form & Culture. New York: Continuum. ISBN 978-0826429360. OCLC 231585586.

- Dupuis, Dominique (2005). Au début était le jaune: une histoire subjective de la bande dessinée (in French). Paris: PLG. ISBN 9782952272902. OCLC 74312669.

- Estren, Mark James (1993). A History of Underground Comics (3rd ed.). Berkeley, CA: Ronin Publishing. ISBN 9780914171645. OCLC 27476913.

- Filippini, Henri (2005). Dictionnaire de la bande dessinée (in French). Paris: Bordas. p. 912. ISBN 9782047320839. Retrieved January 7, 2013.

- Gabilliet, Jean-Paul (2010). Of Comics and Men. A Cultural History of American Comic Books. Jackson, Miss.: University Press of Mississippi. p. 390. ISBN 9781604732672. OCLC 276816625.

- Harvey, Robert C. (2009). "How Comics Came to Be". In Heer, Jeet; Worcester, Kent (eds.). A Comics Studies Reader. Jackson, Miss.: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9781604731095. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- Harvey, Robert C. (1994). The Art of the Funnies. An Aesthetic History. Jackson, Miss.: University Press of Mississippi. p. 252. ISBN 9780878056743. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- Kaplan, Arie (2008). From Krakow to Krypton. Jews and Comic Books. Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society. ISBN 978-0-8276-0843-6. OCLC 191207851.

- Misiroglu, Gina; Roach, David A., eds. (2004). The Superhero Book. The Ultimate Encyclopedia Of Comic-Book Icons And Hollywood Heroes. Detroit: Visible Ink Press. pp. 725. ISBN 1578591546. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- Nyberg, Amy Kiste (1998). Seal of Approval. The History of the Comics Code. Jackson, Miss.: University Press of Mississippi. p. 224. ISBN 9781578591541.

- Rhoades, Shirrel (2008). A Complete History of American Comic Books. New York: Peter Lang. p. 353. ISBN 978-1433101076. OCLC 175290005.

- Rubis, Florian (March 2012). "Comics From the Crypt to the Top: Panorama des comics en français". DBD (in French) (61). ISSN 1951-4050.

- Ryall, Chris; Tipton, Scott (2009). Comic Books 101. The History, Methods and Madness. Cincinnati, Ohio: Impact. p. 288. ISBN 9781600611872. OCLC 233931259.

- Sanders, Joe Sutcliff (2010). The Rise of the American Comics Artist. Creators and Contexts. Jackson, Miss.: University Press of Mississippi. p. 253. ISBN 9781604737929. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- Thorne, Amy (2010). "Webcomics and Libraries". In Weiner, Robert G. (ed.). Graphic Novels and Comics in Libraries and Archives. Essays on Readers, Research, History and Cataloging. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. ISBN 9780786456932. OCLC 630541381.

- Woods Robert, Virginia (2001). "Comic strips". In Browne, Ray Broadus; Browne, Pat (eds.). The Guide to United States Popular Culture. Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State University Popular Press. ISBN 9780879728212. OCLC 44573365.

- Wright, Bradford W. (2003). Comic Book Nation. The Transformation of Youth Culture in America. Baltimore, Md.; London: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 360. ISBN 9780801874505. OCLC 53175529.

Further reading

- Coogan, Peter (2006). Superhero: The Secret Origin of a Genre. Austin, Texas: MonkeyBrain Books.