Highlife

Highlife is a music genre that originated in present-day Ghana early in the 20th century, during its history as a colony of the British Empire. It uses the melodic and main rhythmic structures of traditional Akan music, but is played with Western instruments. Highlife is characterised by jazzy horns and multiple guitars which lead the band. Recently it has acquired an uptempo, synth-driven sound.[1][2][3]

| Highlife | |

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins |

|

| Cultural origins | 1900s (decade), Gold Coast, British West Africa (modern-day Ghana) |

| Typical instruments | |

| Derivative forms | |

Highlife gained popularity among the Igbo people of Nigeria following World War II, becoming the country's most popular music genre in 1960.[4]

History

The following arpeggiated highlife guitar part is modeled after an Afro-Cuban guajeo.[5] The pattern of attack-points is nearly identical to the 3-2 clave motif guajeo as shown below. The bell pattern known in Cuba as clave is indigenous to Ghana and Nigeria, and is used in highlife.[6]

In the 1920s, Ghanaian musicians incorporated foreign influences like the foxtrot and calypso with Ghanaian rhythms like osibisaba (Fante).[7] Highlife was associated with the local African aristocracy during the colonial period, and was played by numerous bands including the Jazz Kings, Cape Coast Sugar Babies, and Accra Orchestra along the country's coast.[7] The high class audience members who enjoyed the music in select clubs gave the music its name. The dance orchestra leader Yebuah Mensah (E.T. Mensah’s older brother) told John Collins in 1973 that the term 'highlife' appeared in the early 1920s "as a catch-phrase for the orchestrated indigenous songs played at [exclusive] clubs by such early dance bands as the Jazz Kings, the Cape Coast Sugar Babies, the Sekondi Nanshamang and later the Accra Orchestra. The people outside called it the highlife as they did not reach the class of the couples going inside, who not only had to pay a relatively high entrance fee of about 7s 6d (seven shillings and sixpence), but also had to wear full evening dress, including top-hats if they could afford it."[8] From the 1930s, Highlife spread via Ghanaian workers to Sierra Leone, Liberia, Nigeria and Gambia among other West African countries, where the music quickly gained popularity.

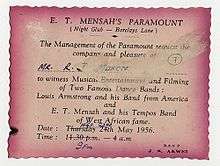

In the 1940s, the music diverged into two distinct streams: dance band highlife and guitar band highlife. Guitar band highlife featured smaller bands and, at least initially, was most common in rural areas. Because of the history of stringed instruments like the seprewa in the region, musicians were happy to incorporate the guitar. They also used the dagomba style, borrowed from Kru sailors from Liberia, to create highlife's two-finger picking style.[7] Guitar band highlife also featured singing, drums and claves. E.K. Nyame and his Akan Trio helped to popularize guitar band highlife, and would release over 400 records during Nyame's lifetime.[7] Dance band highlife, by contrast, was more rooted in urban settings. In the post-war period, larger dance orchestras began to be replaced by smaller professional dance bands, typified by the success of E.T. Mensah and the Tempos. As foreign troops departed, the primary audiences became increasingly Ghanaian, and the music changed to cater to their tastes. Mensah's fame soared after he played with Louis Armstrong in Accra in May 1956, and he eventually earned the nickname, the "King of Highlife".[7] Also important from the 1950s onward was musician King Bruce, who served as band leader to the Black Beats. Some other early bands were, the Red Spots, the Rhythm Aces, the Ramblers and Broadway-Uhuru.

Artists

Artists who perform highlife include:

Ghana

- Nana Acheampong

- Akosua Agyapong

- Gyedu-Blay Ambolley

- Kofi Kinaata

- Nana Ampadu

- Ofori Amponsah

- Kojo Antwi

- Awurama Badu

- Kay Benyarko

- Ben Brako

- Amandzeba Nat Brew

- A. B. Crentsil

- George Darko

- Amakye Dede

- Alhaji K. Frimpong

- Daasebre Gyamena

- Kakaiku

- Bisa Kdei

- Paa Kow

- Kwabena Kwabena

- King Bruce

- Alex Konadu

- Daddy Lumba

- C.K. Mann

- E. T. Mensah

- Joe Mensah

- Nakorex

- Koo Nimo

- Rex Omar

- Osibisa

- Samuel Owusu

- Ebo Taylor

- Pat Thomas

- Paapa Yankson

- Kuami Eugene

- King Promise

- Kidi

Nigeria

- Adeolu Akinsanya

- Babá Ken Okulolo

- Bobby Benson

- Bright Chimezie

- Bola Johnson

- Chief Stephen Osita Osadebe

- Cardinal Rex Jim Lawson

- Dr Sir Warrior

- Eddy Okonta

- Fatai Rolling Dollar

- Fela Kuti

- Femi Kuti

- Fela Sowande

- Flavour N'abania

- Orlando Owoh

- Oliver De Coque

- Oriental Brothers

- Osita Osadebe

- Prince Nico Mbarga

- Roy Chicago

- Victor Olaiya

- Victor Uwaifo

- Wilberforce Echezona

Highlife in jazz

- Saxophonist Pharoah Sanders recorded a song called "High Life" on Rejoice (1981).

- Pierre Dørge and his New Jungle Orchestra played in the highlife style, e.g. on Even the Moon Is Dancing (1985).

- Guitarist Sonny Sharrock had a song called "Highlife" on the album of the same name (1990).

- Craig Harris (trombone) had a song called "High Life" on the album F-Stops (1993)

- High Life is an album by jazz saxophonist Wayne Shorter that was released on Verve Records in 1995.

- Pianist Randy Weston recorded an album called Highlife in 1963, featuring compositions by West African musicians Bobby Benson ("Niger Mambo") and Guy Warren ("Mystery of Love").

- Marcus Miller (bassist, multi-instrumentalist and producer) recorded a song called "Hylife" from the album Afrodeezia released on 17 March 2015.

References

- "Igbo Highlife Music". Pamela Stitch. 17 July 2011. Archived from the original on 1 October 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- Oti, Sonny (2009). Highlife Music in West Africa. African Books Collective. ISBN 978-978-8422-08-2.

- Davies, Carole Boyce (2008). Encyclopedia of the African diaspora: Origins, experiences, and culture. ABC-CLIO, Inc. p. 525. ISBN 978-1-85109-700-5.

- "Highlife was the most popular music in 1960 when we gained our independence". Pulse Nigeria. October 1, 2017. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- Eyre, Banning (2006: 9). "Highlife guitar example" Africa: Your Passport to a New World of Music. Alfred Pub. ISBN 0-7390-2474-4

- Peñalosa, David (2010: 247). The Clave Matrix; Afro-Cuban Rhythm: Its Principles and African Origins. Redway, CA: Bembe Inc. ISBN 1-886502-80-3.

- Salm, Steven J.; Falola, Toyin (2002). Culture and Customs of Ghana. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 181–185. ISBN 9780313320507. Retrieved 30 May 2017.

- Collins, John (1986). E. T. Mensah: King of Highlife. London: Off The Record Press. p. 10.

Further reading

- Collins, John (1985). Music Makers of West Africa. Washington (DC): Three Continents Press. ISBN 0-89410-076-9. also Colorado:Passeggiata Press.

- Collins, John (1992). West African Pop Roots. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. ISBN 0-87722-916-3.

- Collins, John (1996). E. T. Mensah King of Highlife. Anansesem. ISBN 9-98855-217-3.

- Collins, John (2016). Highlife Giants: West African Dance Band Pioneers. Abuja (Nigeria): Cassava Republic Press. ISBN 978-978-50238-1-7.