Hermeticism

Hermeticism, also called Hermetism,[1][2] is a religious, philosophical, and esoteric tradition based primarily upon writings attributed to Hermes Trismegistus ("thrice-greatest Hermes").[3] These writings have greatly influenced the Western esoteric tradition and were considered to be of great importance during both the Renaissance[4] and the Reformation.[5] The tradition traces its origin to a prisca theologia, a doctrine that affirms the existence of a single, true theology that is present in all religions and that was given by God to man in antiquity.[6][7]

| Part of a series on |

| Hermeticism |

|---|

|

| Mythology |

| Hermetica |

|

"Three Parts of the Wisdom of the Whole Universe" |

| Movements |

|

| Orders |

|

| Topics |

|

| People |

|

| Part of a series on |

| Spirituality |

|---|

|

Spiritual experience

|

|

Spiritual development |

| Influences |

|

Western General

Antiquity Medieval Early modern Modern |

|

Asian Pre-historic

Iran India East-Asia |

| Research |

|

Many writers, including Lactantius, Cyprian of Carthage,[8] Marsilio Ficino, Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, Giordano Bruno, Tommaso Campanella, Sir Thomas Browne, and Ralph Waldo Emerson, considered Hermes Trismegistus to be a wise pagan prophet who foresaw the coming of Christianity.[9][10]

Much of the importance of Hermeticism arises from its connection with the development of science during the time from 1300 to 1600 AD. The prominence that it gave to the idea of influencing or controlling nature led many scientists to look to magic and its allied arts (e.g., alchemy, astrology) which, it was thought, could put nature to the test by means of experiments. Consequently, it was the practical aspects of Hermetic writings that attracted the attention of scientists.[11] Isaac Newton placed great faith in the concept of an unadulterated, pure, ancient doctrine, which he studied vigorously to aid his understanding of the physical world.[12]

Etymology

The term Hermetic is from the medieval Latin hermeticus, which is derived from the name of the Greek god Hermes. In English, it has been attested since the 17th century, as in "Hermetic writers" (e.g., Robert Fludd).

The word Hermetic was used by John Everard in his English translation of The Pymander of Hermes, published in 1650.[13]

Mary Anne Atwood mentioned the use of the word Hermetic by Dufresnoy in 1386.[14][15]

The synonymous term Hermetical is also attested in the 17th century. Sir Thomas Browne in his Religio Medici of 1643 wrote: "Now besides these particular and divided Spirits, there may be (for ought I know) a universal and common Spirit to the whole world. It was the opinion of Plato, and is yet of the Hermeticall Philosophers." (R. M. Part 1:2)

Hermes Trimegistus supposedly invented the process of making a glass tube airtight (a process in alchemy) using a secret seal. Hence, the term "completely sealed" is implied in "hermetically sealed" and the term "hermetic" is also equivalent to "occult" or hidden.[16]

History

Late Antiquity

In Late Antiquity, Hermetism[17] emerged in parallel with early Christianity, Gnosticism, Neoplatonism, the Chaldaean Oracles, and late Orphic and Pythagorean literature. These doctrines were "characterized by a resistance to the dominance of either pure rationality or doctrinal faith."[18]

The texts now known as the Corpus Hermeticum are dated by modern translators and most scholars as beginning of 2nd century or earlier.[19][20][21][22] These texts dwell upon the oneness and goodness of God, urge purification of the soul, and expand on the relationship between mind and spirit. Their predominant literary form is the dialogue: Hermes Trismegistus instructs a perplexed disciple upon various teachings of the hidden wisdom.

Renaissance

Plutarch's mention of Hermes Trismegistus dates back to the 1st century AD, and Tertullian, Iamblichus, and Porphyry were all familiar with Hermetic writings.[23]

After centuries of falling out of favor, Hermeticism was reintroduced to the West when, in 1460, a man named Leonardo de Candia Pistoia[24] brought the Corpus Hermeticum to Pistoia. He was one of many agents sent out by Pistoia's ruler, Cosimo de' Medici, to scour European monasteries for lost ancient writings.[25]

In 1614, Isaac Casaubon, a Swiss philologist, analyzed the Greek Hermetic texts for linguistic style. He concluded that the writings attributed to Hermes Trismegistus were not the work of an ancient Egyptian priest but in fact dated to the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD.[26][27]

Even in light of Casaubon's linguistic discovery (and typical of many adherents of Hermetic philosophy in Europe during the 16th and 17th centuries), Thomas Browne in his Religio Medici (1643) confidently stated: "The severe schools shall never laugh me out of the philosophy of Hermes, that this visible world is but a portrait of the invisible." (R. M. Part 1:12)

In 1678, however, flaws in Casaubon's dating were discerned by Ralph Cudworth, who argued that Casaubon's allegation of forgery could only be applied to three of the seventeen treatises contained within the Corpus Hermeticum. Moreover, Cudworth noted Casaubon's failure to acknowledge the codification of these treatises as a late formulation of a pre-existing oral tradition. According to Cudworth, the texts must be viewed as a terminus ad quem and not a terminus a quo. Lost Greek texts, and many of the surviving vulgate books, contained discussions of alchemy clothed in philosophical metaphor.[28]

In the 19th century, Walter Scott placed the date of the Hermetic texts shortly after 200 AD, but W. Flinders Petrie placed their origin between 200 and 500 BC.[29]

Modern era

In 1945, Hermetic texts were found near the Egyptian town Nag Hammadi. One of these texts had the form of a conversation between Hermes and Asclepius. A second text (titled On the Ogdoad and Ennead) told of the Hermetic mystery schools. It was written in the Coptic language, the latest and final form in which the Egyptian language was written.[30]

According to Geza Vermes, Hermeticism was a Hellenistic mysticism contemporaneous with the Fourth Gospel, and Hermes Tresmegistos was "the Hellenized reincarnation of the Egyptian deity Thoth, the source of wisdom, who was believed to deify man through knowledge (gnosis)."[31]

Gilles Quispel says "It is now completely certain that there existed before and after the beginning of the Christian era in Alexandria a secret society, akin to a Masonic lodge. The members of this group called themselves 'brethren,' were initiated through a baptism of the Spirit, greeted each other with a sacred kiss, celebrated a sacred meal and read the Hermetic writings as edifying treatises for their spiritual progress."[32] On the other hand, Christian Bull argues that "there is no reason to identify [Alexandria] as the birthplace of a 'Hermetic lodge' as several scholars have done. There is neither internal nor external evidence for such an Alexandrian 'lodge', a designation that is alien to the ancient world and carries Masonic connotations."[33]

Philosophy

In Hermeticism, the ultimate reality is referred to variously as God, the All, or the One. God in the Hermetica is unitary and transcendent: he is one and exists apart from the material cosmos. Hermetism is therefore profoundly monotheistic although in a deistic and unitarian understanding of the term. "For it is a ridiculous thing to confess the World to be one, one Sun, one Moon, one Divinity, and yet to have, I know not how many gods."[34]

Its philosophy teaches that there is a transcendent God, or Absolute, in which we and the entire universe participate. It also subscribes to the idea that other beings, such as aeons, angels and elementals, exist within the universe.

Prisca theologia

Hermeticists believe in a prisca theologia, the doctrine that a single, true theology exists, that it exists in all religions, and that it was given by God to man in antiquity.[6][7] In order to demonstrate the truth of the prisca theologia doctrine, Christians appropriated the Hermetic teachings for their own purposes. By this account, Hermes Trismegistus was (according to the fathers of the Christian church) either a contemporary of Moses[35] or the third in a line of men named Hermes—Enoch, Noah, and the Egyptian priest-king who is known to us as Hermes Trismegistus.[36][37]

"As above, so below"

The actual text of that maxim, as translated by Dennis W. Hauck from The Emerald Tablet of Hermes Trismegistus, is: "That which is Below corresponds to that which is Above, and that which is Above corresponds to that which is Below, to accomplish the miracle of the One Thing."[38] Thus, whatever happens on any level of reality (physical, emotional, or mental) also happens on every other level.

This principle, however, is more often used in the sense of the microcosm and the macrocosm. The microcosm is oneself, and the macrocosm is the universe. The macrocosm is as the microcosm and vice versa; within each lies the other, and through understanding one (usually the microcosm) a person may understand the other.[39]

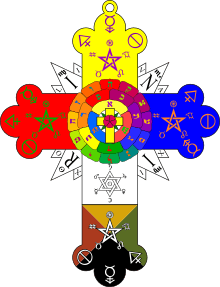

The three parts of the wisdom of the whole universe

Alchemy (the operation of the Sun): Alchemy is not merely the changing of lead into gold.[40] It is an investigation into the spiritual constitution, or life, of matter and material existence through an application of the mysteries of birth, death, and resurrection.[41] The various stages of chemical distillation and fermentation, among other processes, are aspects of these mysteries that, when applied, quicken nature's processes in order to bring a natural body to perfection.[42] This perfection is the accomplishment of the magnum opus (Latin for "Great Work").

Astrology (the operation of the stars): Hermes claims that Zoroaster discovered this part of the wisdom of the whole universe, astrology, and taught it to man.[43] In Hermetic thought, it is likely that the movements of the planets have meaning beyond the laws of physics and actually hold metaphorical value as symbols in the mind of The All, or God. Astrology has influences upon the Earth, but does not dictate our actions, and wisdom is gained when we know what these influences are and how to deal with them.

Theurgy (the operation of the gods): There are two different types of magic, according to Giovanni Pico della Mirandola's Apology, completely opposite of each other. The first is Goëtia (Greek: γοητεια), black magic reliant upon an alliance with evil spirits (i.e., demons). The second is Theurgy, divine magic reliant upon an alliance with divine spirits (i.e., angels, archangels, gods).[44]

"Theurgy" translates to "The Science or Art of Divine Works" and is the practical aspect of the Hermetic art of alchemy.[45] Furthermore, alchemy is seen as the "key" to theurgy,[46] the ultimate goal of which is to become united with higher counterparts, leading to the attainment of Divine Consciousness.[45]

Reincarnation

Reincarnation is mentioned in Hermetic texts. Hermes Trismegistus asked:

O son, how many bodies have we to pass through, how many bands of demons, through how many series of repetitions and cycles of the stars, before we hasten to the One alone?[47]

Good and evil

Hermes explains in Book 9 of the Corpus Hermeticum that nous (reason and knowledge) brings forth either good or evil, depending upon whether one receives one's perceptions from God or from demons. God brings forth good, but demons bring forth evil. Among the evils brought forth by demons are: "adultery, murder, violence to one's father, sacrilege, ungodliness, strangling, suicide from a cliff and all such other demonic actions".[48]

This provides evidence that Hermeticism includes a sense of morality. However, the word "good" is used very strictly. It is restricted to references to God.[49] It is only God (in the sense of the nous, not in the sense of the All) who is completely free of evil. Men are prevented from being good because man, having a body, is consumed by his physical nature, and is ignorant of the Supreme Good.[50]

A focus upon the material life is said to be the only thing that offends God:

As processions passing in the road cannot achieve anything themselves yet still obstruct others, so these men merely process through the universe, led by the pleasures of the body.[51]

One must create, one must do something positive in one's life, because God is a generative power. Not creating anything leaves a person "sterile" (i.e., unable to accomplish anything).[52]

Cosmogony

A creation story is told by God to Hermes in the first book of the Corpus Hermeticum. It begins when God, by an act of will, creates the primary matter that is to constitute the cosmos. From primary matter God separates the four elements (earth, air, fire, and water). Then God orders the elements into the seven heavens (often held to be the spheres of Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, the Sun, and the Moon, which travel in circles and govern destiny).

"The Word (Logos)" then leaps forth from the materializing four elements, which were unintelligent. Nous then makes the seven heavens spin, and from them spring forth creatures without speech. Earth is then separated from water, and animals (other than man) are brought forth.

The God then created androgynous man, in God's own image, and handed over his creation.

The Fall of Man

Man carefully observed the creation of nous and received from God man's authority over all creation. Man then rose up above the spheres' paths in order to better view creation. He then showed the form of the All to Nature. Nature fell in love with the All, and man, seeing his reflection in water, fell in love with Nature and wished to dwell in it. Immediately, man became one with Nature and became a slave to its limitations, such as sex and sleep. In this way, man became speechless (having lost "the Word") and he became "double", being mortal in body yet immortal in spirit, and having authority over all creation yet subject to destiny.[53]

Alternative Account to The Fall of Man

An alternative account of the fall of man, preserved in the Discourses of Isis to Horus, is as follows:

God, having created the universe, then created the divisions, the worlds, and various gods and goddesses, whom he appointed to certain parts of the universe. He then took a mysterious transparent substance, out of which he created human souls. He appointed the souls to the astral region, which is just above the physical region.

He then assigned the souls to create life on Earth. He handed over some of his creative substance to the souls and commanded them to contribute to his creation. The souls then used the substance to create the various animals and forms of physical life. Soon after, however, the souls began to overstep their boundaries; they succumbed to pride and desired to be equal to the highest gods.

God was displeased and called upon Hermes to create physical bodies that would imprison the souls as a punishment for them. Hermes created human bodies on earth, and God then told the souls of their punishment. God decreed that suffering would await them in the physical world, but he promised them that, if their actions on Earth were worthy of their divine origin, their condition would improve and they would eventually return to the heavenly world. If it did not improve, he would condemn them to repeated reincarnation upon Earth.[54]

As a religion

Tobias Churton, Professor of Western Esotericism at the University of Exeter, states, "The Hermetic tradition was both moderate and flexible, offering a tolerant philosophical religion, a religion of the (omnipresent) mind, a purified perception of God, the cosmos, and the self, and much positive encouragement for the spiritual seeker, all of which the student could take anywhere."[55] Lutheran Bishop James Heiser recently evaluated the writings of Marsilio Ficino and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola as an attempted "Hermetic Reformation".[56]

Religious and philosophical texts

Hermeticists generally attribute 42 books to Hermes Trismegistus, although many more have been attributed to him. Most of them, however, are said to have been lost when the Great Library of Alexandria was destroyed.

There are three major texts that contain Hermetic doctrines:

- The Corpus Hermeticum is the most widely known Hermetic text. It has 18 chapters, which contain dialogues between Hermes Trismegistus and a series of other men. The first chapter contains a dialogue between Poimandres (who is identified as God) and Hermes. This is the first time that Hermes is in contact with God. Poimandres teaches the secrets of the universe to Hermes. In later chapters, Hermes teaches others, such as his son Tat and Asclepius.

- The Emerald Tablet of Hermes Trismegistus is a short work which contains a phrase that is well known in occult circles: "As above, so below." The actual text of that maxim, as translated by Dennis W. Hauck, is: "That which is Below corresponds to that which is Above, and that which is Above corresponds to that which is Below, to accomplish the miracle of the One Thing".[38] The Emerald Tablet also refers to the three parts of the wisdom of the whole universe. Hermes states that his knowledge of these three parts is the reason why he received the name Trismegistus ("Thrice Great" or "Ao-Ao-Ao" [which mean "greatest"]). As the story is told, the Emerald Tablet was found by Alexander the Great at Hebron, supposedly in the tomb of Hermes.[57]

- The Perfect Sermon (also known as The Asclepius, The Perfect Discourse, or The Perfect Teaching) was written in the 2nd or 3rd century AD and is a Hermetic work similar in content to The Corpus Hermeticum.

Other important original Hermetic texts include the Discourses of Isis to Horus,[58] which consists of a long dialogue between Isis and Horus on the fall of man and other matters; the Definitions of Hermes to Asclepius;[59] and many fragments, which are chiefly preserved in the anthology of Stobaeus.

There are additional works that, while not as historically significant as the works listed above, have an important place in neo-Hermeticism:

- The Kybalion: Hermetic Philosophy is a book anonymously published in 1912 by three people who called themselves the "Three Initiates", and claims to expound upon essential Hermetic principles.

- A Suggestive Inquiry into Hermetic Philosophy and Alchemy was written by Mary Anne Atwood and originally published anonymously in 1850. This book was withdrawn from circulation by Atwood but was later reprinted, after her death, by her longtime friend Isabelle de Steiger. Isabelle de Steiger was a member of the Golden Dawn.

A Suggestive Inquiry was used for the study of Hermeticism and resulted in several works being published by members of the Golden Dawn:[60]

- Arthur Edward Waite, a member and later the head of the Golden Dawn, wrote The Hermetic Museum and The Hermetic Museum Restored and Enlarged. He edited The Hermetic and Alchemical Writings of Paracelsus, which was published as a two-volume set. He considered himself to be a Hermeticist and was instrumental in adding the word "Hermetic" to the official title of the Golden Dawn.[61]

- William Wynn Westcott, a founding member of the Golden Dawn, edited a series of books on Hermeticism titled Collectanea Hermetica. The series was published by the Theosophical Publishing Society.[62]

- Initiation Into Hermetics is the title of the English translation of the first volume of Franz Bardon's three-volume work dealing with self-realization within the Hermetic tradition.

Societies

When Hermeticism was no longer endorsed by the Christian church, it was driven underground, and several Hermetic societies were formed. The western esoteric tradition is now steeped in Hermeticism. The work of such writers as Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, who attempted to reconcile Jewish kabbalah and Christian mysticism, brought Hermeticism into a context more easily understood by Europeans during the time of the Renaissance.

A few primarily Hermetic occult orders were founded in the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance.

Hermetic magic underwent a 19th-century revival in Western Europe,[63] where it was practiced by groups such as the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, Aurum Solis, and Ragon. It was also practiced by individual persons, such as Eliphas Lévi, William Butler Yeats, Arthur Machen, Frederick Hockley, and Kenneth M. Mackenzie.[64]

Many Hermetic, or Hermetically influenced, groups exist today. Most of them are derived from Rosicrucianism, Freemasonry, or the Golden Dawn.

Rosicrucianism

Rosicrucianism is a movement which incorporates the Hermetic philosophy. It dates back to the 17th century. The sources dating the existence of the Rosicrucians to the 17th century are three German pamphlets: the Fama, the Confessio Fraternitatis, and The Chymical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreutz.[65] Some scholars believe these to be hoaxes and say that later Rosicrucian organizations are the first actual appearance of a Rosicrucian society.[66] This argument is hard to sustain given that original copies are in existence, including a Fama Fraternitatis at the University of Illinois and another in the New York Public Library.

The Rosicrucian Order consists of a secret inner body and a public outer body that is under the direction of the inner body. It has a graded system in which members move up in rank and gain access to more knowledge. There is no fee for advancement. Once a member has been deemed able to understand the teaching, he moves on to the next higher grade.

The Fama Fraternitatis states that the Brothers of the Fraternity are to profess no other thing than "to cure the sick, and that gratis".

The Rosicrucian spiritual path incorporates philosophy, kabbalah, and divine magic.

The Order is symbolized by the rose (the soul) and the cross (the body). The unfolding rose represents the human soul acquiring greater consciousness while living in a body on the material plane.

Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn

Unlike the Societas Rosicruciana in Anglia, the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn was open to both sexes and treated them as equals. The Order was a specifically Hermetic society that taught alchemy, kabbalah, and the magic of Hermes, along with the principles of occult science.

The Golden Dawn maintained the tightest of secrecy, which was enforced by severe penalties for those who disclosed its secrets. Overall, the general public was left oblivious of the actions, and even of the existence, of the Order, so few if any secrets were disclosed.[67]

Its secrecy was broken first by Aleister Crowley in 1905 and later by Israel Regardie in 1937. Regardie gave a detailed account of the Order's teachings to the general public.[68]

Regardie had once claimed that there were many occult orders which had learned whatever they knew of magic from what had been leaked from the Golden Dawn by those whom Regardie deemed "renegade members".

The Stella Matutina was a successor society of the Golden Dawn.

Esoteric Christianity

Hermeticism remains influential within esoteric Christianity, especially in Martinism. Influential 20th century and early 21st century writers in the field include Valentin Tomberg and Sergei O. Prokofieff. The Kybalion somewhat explicitly owed itself to Christianity, and the Meditations on the Tarot was one important book illustrating the theory and practice of Christian Hermeticism.

Mystical Neopaganism

Hermeticism remains influential within Neopaganism, especially in Hellenism.

See also

- Bibliotheca Philosophica Hermetica

- Hellenistic magic

- Hermeneutics

- Hermeticists (category)

- Hermetism and other religions

- Perennial philosophy

- Recapitulation theory

- Renaissance magic

- Sex magic

- Thelema

- Thelemic mysticism

- Theosophy (Blavatskian)

References

- Audi, Robert (1999). The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 378. ISBN 0521637228.

- Reese, William L. (1980). Dictionary of Philosophy and Religion. Sussex: Harvester Press. pp. 108 and 221. ISBN 0855271477.

- Churton p. 4

- "Hermeticism" The Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Religions

- Heiser, James D., Prisci Theologi and the Hermetic Reformation in the Fifteenth Century, Repristination Press, Texas: 2011. ISBN 978-1-4610-9382-4

- Yates, F., Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition, Routledge, London, 1964, pp 14–18 and pp. 433–434

- Hanegraaff, W. J., New Age Religion and Western Culture, SUNY, 1998, p 360.

- Jafar, Imad (2015). "Enoch in the Islamic Tradition". Sacred Web: A Journal of Tradition and Modernity. 36: 53.

- Yates, F., Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition, Routledge, London, 1964, pp 9–15 and pp 61–66 and p. 413

- Heiser, J., "Prisci Theologi and the Hermetic Reformation in the Fifteenth Century", Repristination Press, Texas, 2011 ISBN 978-1-4610-9382-4

- Tambiah (1990), Magic, Science, Religion, and the scope of Rationality, pp. 25–26

- Tambiah (1990), 28

- Collectanea Hermetica Edited by W. Wynn. Westcott Volume 2.

- See Dufresnoy, Histoire del' Art Hermetique, vol. iii. Cat. Gr. MSS.

- A Suggestive Inquiry into Hermetic Philosophy and Alchemy by Mary Anne Atwood 1850.

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com.

- van den Broek and Hanegraaff (1997) distinguish Hermetism in late antiquity from Hermeticism in the Renaissance revival.

- van den Broek and Hanegraaff (1997), p. vii.

- Copenhaver, Brian P. (1995). "Introduction". Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation, with Notes and Introduction. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521425438.

Scholars generally locate the theoretical Hermetica, 100 to 300 CE; most would put C.H. I toward the beginning of that time. [...] [I]t should be noted that Jean-Pierre Mahe accepts a second-century limit only for the individual texts as they stand, pointing out that the materials on which they are based may come from the first century CE or even earlier. [...] To find theoretical Hermetic writings in Egypt, in Coptic [...] was a stunning challenge to the older view, whose major champion was Father Festugiere, that the Hermetica could be entirely understood in a post-Platonic Greek context.

- Copenhaver, Brian P. (1995). "Introduction". Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation, with Notes and Introduction. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521425438.

[...] survivals from the earliest Hermetic literature, some conceivably as early as the fourth century BCE

- Copenhaver, Brian P. (1995). "Introduction". Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation, with Notes and Introduction. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521425438.

[...] Hermetic sentences derived from similar elements in ancient Egyptian wisdom literature, especially the genre called "Instructions" that reached back to the Old Kingdom

- Frowde, Henry. Transactions Of The Third International Congress For The History Of Religions Vol 1.

[T]he Kore Kosmou, is dated probably to 510 B.C., and certainly within a century after that, by an allusion to the Persian rule [...] the Definitions of Asclepius [...] as early as 350 B.C.

- Stephan A. Hoeller, On the Trail of the Winged God—Hermes and Hermeticism Throughout the Age, Gnosis: A Journal of Western Inner Traditions (Vol. 40, Summer 1996).

- This Leonardo di Pistoia was a monk "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-01-01. Retrieved 2007-01-27.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), not to be confused with the artist Leonardo da Pistoia who was not born until c. 1483 CE.

- Salaman, Van Oyen, Wharton and Mahé,The Way of Hermes, p. 9

- Tambiah (1990), Magic, Science, Religion, and the Scope of Rationality, pp. 27–28.

- The Way of Hermes, p. 9.

- "Corpus Hermeticum". www.granta.demon.co.uk.

- Abel and Hare p. 7.

- The Way of Hermes, pp. 9–10.

- Vermes, Geza (2012). Christian Beginnings. Allen Lane the Penguin Press. p. 128.

- Quispel, Gilles (2004). Preface to The Way of Hermes: New Translations of The Corpus Hermeticum and The Definitions of Hermes Trismegistus to Asclepius. Translated by Salaman, Clement; van Oyen, Dorine; Wharton, William D.; Mahé, Jean-Pierre. Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions.

- Bull 2018, p. 454

- "The Divine Pymander: The Tenth Book, the Mind to Hermes". www.sacred-texts.com.

- Yates, F., Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition, Routledge, London, 1964, p 27 and p 293

- Yates, F., Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition, Routledge, London, 1964, p52

- Copenhaver, B.P., "Hermetica", Cambridge University Press, 1992, p xlviii.

- Scully p. 321.

- Garstin p. 35.

- Hall, Manly Palmer (1925). The Hermetic Marriage: Being a Study in the Philosophy of the Thrice Greatest Hermes. Hall Publishing Company. p. 227.

- Eliade, Mircea (1978). The Forge and the Crucible: The Origins and Structure of Alchemy. University of Chicago Press. pp. 149, 155–157. ISBN 9780226203904.

- Geber Summa Perfectionis

- Powell pp. 19–20.

- Garstin p. v

- Garstin p. 6

- Garstin p. vi

- The Way of Hermes p. 33.

- The Way of Hermes p. 42.

- The Way of Hermes p. 28.

- The Way of Hermes p. 47.

- The Way of Hermes pp. 32–3.

- The Way of Hermes p. 29.

- The Poimandres

- Scott, Walter (1 January 1995). Hermetica[: The Ancient Greek and Latin Writings which Contain Religious Or Philosophic Teachings Ascribed to Hermes Trismegistus. Introduction, texts, and translations. Volume 1. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 9781564594815 – via Google Books.

- Churton p. 5.

- Heiser, James D., Prisci Theologi and the Hermetic Reformation in the Fifteenth Century, Repristination Press: Texas, 2011. ISBN 978-1-4610-9382-4

- Abel & Hare p. 12.

- "Walter Scott, Hermetica Volume 1, pg 457".

- Salaman, Clement (August 23, 2000). "The Way of Hermes: Translations of The Corpus Hermeticum and The Definitions of Hermes Trismegistus to Asclepius". Inner Traditions – via Google Books.

- "A Suggestive Inquiry into Hermetic Philosophy and Alchemy" with an introduction by Isabelle de Steiger

- "Hermetic Papers of A. E. Waite: the Unknown Writings of a Modern Mystic" Edited by R. A. Gilbert.

- "'The Pymander of Hermes' Volume 2, Collectanea Hermetica" published by The Theosophical Publishing Society in 1894.

- Regardie p. 17.

- Regardie pp. 15–6.

- Yates, Frances (1972). The Rosicrucian Enlightenment. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. ISBN 0-7100-7380-1.

- "Prof. Carl Edwin Lindgren, "The Rose Cross, A Historical and Philosophical View"". Archived from the original on 2012-11-08.

- Regardie pp. 15–7.

- Regardie p. ix.

Bibliography

- Abel, Christopher R.; Hare, William O. (1997). Hermes Trismegistus: An Investigation of the Origin of the Hermetic Writings. Sequim: Holmes Publishing Group.

- Anonymous (2002). Meditations on the Tarot: A Journey into Christian Hermeticism. New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Penguin.

- Bull, Christian H. (2018). The Tradition of Hermes Trismegistus: The Egyptian Priestly Figure as a Teacher of Hellenized Wisdom. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-37084-5.

- Churton, Tobias. The Golden Builders: Alchemists, Rosicrucians, and the First Freemasons. New York: Barnes and Noble, 2002.

- Copenhaver, Brian P. (1992). Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a new English translation, with notes and introduction (1st ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-42543-3.

- Ebeling, Florian (2007) [2005]. The Secret History of Hermes Trismegistus: Hermeticism from Ancient to Modern Times. Translated by David Lorton. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-4546-0.

- Fowden, Garth (1986). The Egyptian Hermes: A Historical Approach to the Late Pagan Mind. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-32583-7.

- Garstin, E.J. Langford (2004). Theurgy or The Hermetic Practice. Berwick: Ibis Press. Published Posthumously

- Hanegraaff, Wouter J. Esotericism and the Academy: Rejected Knowledge in Western Culture. Cambridge University Press; Reprint 2014.

- Hanegraaff, Wouter J. Western Esotericism: A Guide for the Perplexed. Bloomsbury Academic 2013.

- Heiser, James D. (2011). Prisci Theologi and the Hermetic Reformation in the Fifteenth Century. Texas: Repristination Press. ISBN 978-1-4610-9382-4.

- Hoeller, Stephan A. On the Trail of the Winged God: Hermes and Hermeticism Throughout the Ages, Gnosis: A Journal of Western Inner Traditions (Vol. 40, Summer 1996). Also at "Hermes and Hermeticism". Gnosis.org. Archived from the original on 2009-11-26. Retrieved 2009-11-09.

- Morais, Lui (2013). Alchimia seu Archimagisterium Solis in V libris. Rio de Janeiro: Quártica Premium.

- Powell, Robert A. (1991). Christian Hermetic Astrology: The Star of the Magi and the Life of Christ. Hudson: Anthroposohic Press.

- Regardie, Israel (1940). The Golden Dawn. St. Paul: Llewellyn Publications.

- Salaman, Clement and Van Oyen, Dorine and Wharton, William D. and Mahé, Jean-Pierre (2000). The Way of Hermes: New Translations of The Corpus Hermeticum and The Definitions of Hermes Trismegistus to Asclepius. Rochester: Inner Traditions.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Scully, Nicki (2003). Alchemical Healing: A Guide to Spiritual, Physical, and Transformational Medicine. Rochester: Bear & Company.

- Tambiah, Stanley Jeyaraja (1990). Magic, Science, Religion, and the Scope of Rationality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Van Bladel, Kevin (2009). The Arabic Hermes: From Pagan Sage to Prophet of Science. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-537613-5.

- Yates, Frances (1964). Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-95007-7.

- Massimo Colella, «Il sogno umano della pura assolutezza». Leggendo Luzi postumo, in «Xenia. Trimestrale di Letteratura e Cultura» (Genova), III, 3, 2018, pp. 34-45.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hermeticism. |

- Online Version of the Corpus Hermeticum, version translated by John Everard in 1650 CE from Latin version

- Online Version of The Virgin of the World of Hermes Trismegistus, version translated by Anna Kingsford and Edward Maitland in 1885 A.D.

- Online version of The Kybalion (1912)

- The Kybalion Resource Page

- The Hermetic Library—A collection of texts and sites relating to Hermeticism

- Hermetic Library Hermetic Library from Hermetic International