Heo Hwang-ok

Heo Hwang-ok is a legendary queen mentioned in Samguk Yusa, a 13th-century Korean chronicle. According to Samguk Yusa she became the wife of King Suro of Geumgwan Gaya at the age of 16, after having arrived by boat from a distant kingdom,[1][2] making her the first queen of Geumgwan Gaya. According to some Korean historians there are more than six million present day Koreans, of which the majority are from Gimhae Kim clan with surnames Heo and 이 (Lee/Yi) that trace their lineage to the legendary queen.[3][2][4] Her native kingdom is believed to be located in India by some; there is, however, no mention of her in any pre-modern Indian sources.[4] There is a tomb in Gimhae, Korea, that is believed by some to be hers,[5] and a memorial in Ayodhya in India.[6][7][8][9]

Origins

The legend of Heo is found in Garakgukgi (the Record of Garak Kingdom) which is currently lost, but referenced within the Samguk Yusa.[10] According to the legend, Heo was a princess of the "Ayuta Kingdom". The extant records do not identify Ayuta except as a distant country. Written sources and popular culture often associate Ayuta with India but there are no records of the legend in India itself.[4] Kim Byung-Mo, an anthropologist from Hanyang University, identified Ayuta with Ayodhya in India based on phonetic similarity.[11] The Indian city now called Ayodhya was called Saketa in the ancient period,[12] though the name Ayodhya did exist in the medieval era[13] when the Samguk Yusa was composed.[14] Grafton K. Mintz and Ha Tae-Hung implied that the Korean reference was actually to the Ayutthaya Kingdom of Thailand.[12] However, according to George Cœdès, the Thai city was not founded until 1350 CE, after the composition of Samguk Yusa.[12][15]

Marriage to Suro

After their marriage, Heo told King Suro that she was 16 years old.[1][2] She stated her given name as "Hwang-ok" ("Yellow Jade") and her family name as "Heo" (or "Hurh"). She described how she came to Gaya as follows: The Heavenly Lord (Sange Je) appeared in her parents's dreams. He told them to send Heo to Suro, who had been chosen as the king of Gaya. The dream showed that the king had not yet found a queen. Heo's father then told her to go to Suro. After two months of a sea journey, she found Beondo, a peach which fruited only every 3000 years.[3]

According to the legend, the courtiers of King Suro had requested him to select a wife from among the maidens they would bring to the court. However, Suro stated that his selection of a wife will be commanded by the Heavens. He commanded Yuch'ŏn-gan to take a horse and a boat to Mangsan-do, an island to the south of the capital. At Mangsan, Yuch'ŏn saw a vessel with a red sail and a red flag. He sailed to the vessel, and escorted it to the shores of Kaya (or Gaya, present-day Kimhae/Gimhae). Another officer, Sin'gwigan went to the palace, and informed the King of the vessel's arrival. The King sent nine clan chiefs, asking them to escort the ship's passengers to the royal palace.[16]

Princess Heo stated that she wouldn't accompany the strangers. Accordingly, the King ordered a tent to be pitched on the slopes of a hill near the palace. The princess then arrived at the tent with her courtiers and slaves. The courtiers included Sin Po (or Sin Bo 신보 申輔) and Cho Kuang (or Jo Gwang 조광 趙匡). Their wives were Mojong 모정(慕貞) and Moryang 모량(慕良) respectively. The twenty slaves carried gold, silver, jewels, silk brocade, and tableware.[17] Before marrying the king, the princess took off her silk trousers (mentioned as a skirt in a different section of Samguk Yusa) and offered them to the mountain spirit. King Suro tells her that he also knew about Heo's arrival in advance, and therefore, did not marry the maidens recommended by his courtiers.[3]

When some of the Queen's escorts decided to return home, King Suro gave each of them thirty rolls of hempen cloth (one roll was of 40 yards). He also gave each person ten bags of rice for the return voyage. A part of the Queen's original convoy, including the two courtiers and their wives, stayed back with her. The queen was given a residence in the inner palace, while the two courtiers and their wives were given separate residences. The rest of her convoy were given a guest house of twenty rooms.[17]

Descendants

Heo and Suro had 12 children, the eldest son was Geodeung. She requested Suro to let two of the children bear her maiden surname. Legendary genealogical records trace the origins of the Gimhae Heo to these two children.[3] The Gimhae Kims trace their origin to the other eight sons, and so do the 이 of Incheon. According to the Jilburam, the remaining seven sons are said to have followed their maternal uncle Po-Ok's footsteps and devoted themselves to Buddhist meditation. They were named Hyejin, Gakcho, Jigam, Deonggyeon, Dumu, Jeongheong and Gyejang.[2] Overall, more than six million Koreans trace their lineage to Queen Heo.[4] The other two were female and were married respectively to a son of Talhae and a noble of Silla.

The legend states that the queen died at the age of 157.[16]

Remains

The tombs believed to be that of Heo and Suro are located in Gimhae, South Korea. A pagoda traditionally held to have been brought to Korea on her ship is located near her grave. The Samguk Yusa reports that the pagoda was erected on her ship in order to calm the god of the ocean and allow the ship to pass. The unusual and rough form of this pagoda, unlike any other in Korea, may lend some credence to the account.[5]

A passage in the Samguk Yusa indicates that King Jilji built a Buddhist temple for the ancestral queen Heo Hwang-ok on the spot where she and King Suro were married.[18] He called the temple Wanghusa ("the Queen's temple") and provided it with ten gyeol of stipend land.[18] A gyeol or kyŏl (결 or 結), varied in size from 2.2 acres to 9 acres (8,903–36,422 m2) depending upon the fertility of the land.[19] The Samguk Yusa also records that the temple was built in 452. The temple was called Wanghusa, or "the Queen's temple." Since there is no other record of Buddhism having been adopted in 5th-century Gaya, modern scholars have interpreted this as an ancestral shrine rather than a Buddhist temple.[5]

Memorial in Ayodhya

Based on the identification of Ayuta with Ayodhya in India, several Koreans believe Heo Hwang-ok to be an Indian princess. In 2001, a Memorial of Heo Hwang-ok was inaugurated by a Korean delegation, which included over a hundred historians and government representatives.[6] In 2016, a Korean delegation proposed to develop the memorial. The proposal was accepted by the Uttar Pradesh chief minister Akhilesh Yadav.[7] On 6 November 2018 on the eve of Deepavali celebration, South Korean first lady Kim Jung-sook laid the foundation stone for the expansion and beautification of the existing memorial.[8][9] She offered tribute at the Queen Heo Memorial, attended a ground-breaking ceremony for the upgrade and beautification of the memorial, attended an elaborate Diwali celebration at Ayodhya along with the present Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh Yogi Adityanath that included cultural shows and lighting of 300,000+ lights on the banks of Saryu River.[20]

As per reports, every year, hundreds of South Koreans visit Ayodhya, the birthplace of the Hindu deity Rama, for paying homage to their legendary queen Heo Hwang-ok, also known as Princess Suriratna.[21]

In popular culture

- Portrayed by Seo Ji-hye in the 2010 MBC TV series Kim Su-ro, The Iron King

- In June 2007, the Indian Ambassador to Seoul Nagesh Rao Parthasarathi (53) wrote a novel, Silk Empress (비단황후), exploring the Indian princess's journey to Korea to marry the Korean King. The novel was published in Korean, with an English edition in progress.[22]

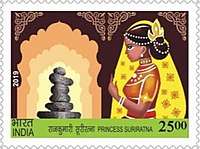

- In February 2019, India and Korea signed an agreement on releasing a joint stamp, commemorating Princess Suriratna (Queen Heo Hwang-ok).[23]

See also

- History of Korea

- Three Kingdoms of Korea

- Buddhist temples in South Korea

- Garakguk

- Indians in Korea

- Koreans in India

- India–South Korea relations

- India – North Korea relations

References

- No. 2039《三國遺事》CBETA 電子佛典 V1.21 普及版 Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine, Taisho Tripitaka Vol. 49, CBETA Chinese Electronic Tripitaka V1.21, Normalized Version, T49n2039_p0983b14(07)

- Kim Choong Soon, 2011, Voices of Foreign Brides: The Roots and Development of Multiculturalism in Korea, AltairaPress, USA, Page 30-35.

- Won Moo Hurh (2011). "I Will Shoot Them from My Loving Heart": Memoir of a South Korean Officer in the Korean War. McFarland. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-0-7864-8798-1.

- "Korean memorial to Indian princess". BBC News. 3 May 2001.

- Kwon Ju-hyeon (권주현) (2003). 가야인의 삶과 문화 (Gayain-ui salm-gwa munhwa, The culture and life of the Gaya people). Seoul: Hyean. pp. 212–214. ISBN 89-8494-221-9.

- "Korean memorial to Indian princess". BBC News. 6 March 2001.

- UP CM announces grand memorial of Queen Huh Wang-Ock, 1 March 2016, WebIndia123

- "UP's Faizabad district to be known as Ayodhya, says Yogi Adityanath". 6 November 2018. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- "Site for Heo Hwang-ok memorial in Ayodhya finalised". 2 November 2018. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- Il-yeon (tr. by Ha Tae-Hung & Grafton K. Mintz) (1972). Samguk Yusa. Seoul: Yonsei University Press. ISBN 89-7141-017-5.

- Choong Soon Kim (2011). Voices of Foreign Brides: The Roots and Development of Multiculturalism in Korea. AltaMira. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-7591-2037-2.

- Robert E. Buswell (1991). Tracing Back the Radiance: Chinul's Korean Way of Zen. University of Hawaii Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-8248-1427-4.

- Jeannine Auboyer (1962). Daily Life In Ancient India. Paris: Phoenix Press.

- John Keay (2000). India: A History. Harper Collins.

- Skand R. Tayal (2015). India and the Republic of Korea: Engaged Democracies. Taylor & Francis. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-317-34156-7.

Historians, however, believe that the Princess of Ayodhya is only a myth.

- James Huntley Grayson (2001). Myths and Legends from Korea: An Annotated Compendium of Ancient and Modern Materials. Psychology Press. pp. 110–116. ISBN 978-0-7007-1241-0.

- Choong Soon Kim (16 October 2011). Voices of Foreign Brides: The Roots and Development of Multiculturalism in Korea. AltaMira Press. pp. 31–33. ISBN 978-0-7591-2037-2.

- Ilyeon, 1972, Samguk Yusa, tr. by Ha, Tae-Hung and Mintz, Grafton K., Yonsei University Press, Seoul, ISBN 89-7141-017-5, p. 168.

- Palais, James B. (1996), Confucian Statecraft & Korean Institutions: Yu Hyŏngwŏn and the Late Chosŏn Dynasty, Seattle: University of Washington Press, p. 363

- South Korean first lady Kim Jung-sook celebrates Diwali in Ayodhya, revives links of Queen Heo, Hindustan Times, 10 July 2018

- This is why hundreds of South Koreans visit Ayodhya every year, Indian express, 10 July 2018

- Indian Envoy in Seoul Authors "Silk Empress" Indian Princess Weds Korean King 2,000 Years Ago, June 2007, The Seoul Times

- India, South Korea sign 6 pacts; to step-up cooperation in infrastructure, combating global crime. The Economic Times. 22 February 2019