Henry rifle

The Henry repeating rifle is a lever-action tubular magazine rifle famed both for its use at the Battle of the Little Bighorn and being the basis for the iconic Winchester rifle of the American Wild West.

| Henry rifle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | Lever-action rifle |

| Place of origin | United States |

| Service history | |

| Used by | United States (Union) Confederate States Polish National Government |

| Wars | American Civil War Indian Wars January Uprising |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Benjamin Tyler Henry |

| Designed | 1860 |

| Manufacturer | New Haven Arms Company |

| Unit cost | $40[1] |

| Produced | 1860–1866 |

| No. built | c. 14,000 |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 9 lb 4 oz (4.2 kg) |

| Length | 44.75 in (113.7 cm) |

| Barrel length | 24 in (61 cm) |

| Caliber | .44 Henry rimfire |

| Action | breech-loading lever action |

| Feed system | 15-round tubular magazine +1 round in the chamber |

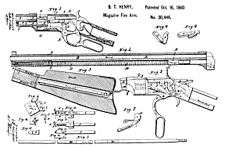

Designed by Benjamin Tyler Henry in 1860, the original Henry was a sixteen shot .44 caliber rimfire breech-loading lever-action rifle. It was introduced in the early 1860s and produced through 1866 in the United States by the New Haven Arms Company. The Henry was adopted in small quantities by the Union in the Civil War, favored for its greater firepower than the standard issue carbine. Many later found their way West, notably in the hands of the Sioux and Cheyenne in their obliteration of Custer's U.S. Cavalry troops in June 1876.

Modern replicas are produced by A. Uberti Firearms and Henry Repeating Arms. Most are chambered in .44-40 Winchester or .45 Long Colt.

History

The original Henry rifle was a sixteen shot .44 caliber rimfire breech-loading lever-action rifle, patented by Benjamin Tyler Henry in 1860 after three years of design work.[2] The Henry was an improved version of the earlier Volition, and later Volcanic. The Henry used copper (later brass) rimfire cartridges with a 216 grain (14.0 gram, 0.490 ounce) bullet over 25 grains (1.6 g, 0.056 oz.) of black powder.

Only 150 to 200 rifles a month were initially produced. Nine hundred were manufactured between summer and October 1862. Production peaked at 290 per month by 1864, bringing the total to 8,000.[3] By the time the run ended in 1866, approximately 14,000 units had been manufactured.

For a Civil War soldier, owning a Henry rifle was a point of pride.[4] Letters home would call them "Sixteen" or "Seventeen"-shooters, depending whether a round was loaded in the chamber. Just 1,731 of the standard rifles were purchased by the government during the Civil War.[5] The Commonwealth of Kentucky purchased a further 50. However 6,000 to 7,000 saw use by the Union on the field through private purchases by soldiers who could afford it. The relative fragility of Henrys compared to Spencers hampered their official acceptance. Another weak point for the Henry was that it could not be equipped with a bayonet. Many infantry soldiers purchased Henrys with their reenlistment bounties of 1864. Most of these units were associated with Sherman's Western troops.

When used correctly, the brass-receiver rifles had an exceptionally high rate of fire compared to any other weapon on the battlefield. Soldiers who saved their pay to buy one believed it would help save their lives. Since tactics had not been developed to take advantage of their firepower, Henrys were frequently used by scouts, skirmishers, flank guards, and raiding parties rather than in regular infantry formations. Confederate Colonel John Mosby, who became infamous for his sudden raids against advanced Union positions, when first encountering the Henry in battle called it "that damned Yankee rifle that can be loaded on Sunday and fired all week."[6] Since then that phrase became associated with the Henry rifle.[7] Those few Confederate troops who came into possession of captured Henry rifles had little way to resupply the ammunition it used, making its widespread use by Confederate forces impractical. The rifle was, however, known to have been used at least in part by some Confederate units in Louisiana, Texas, and Virginia, as well as the personal bodyguards of Confederate President Jefferson Davis.[8] According to firearms historian Herbert G. Houze, one man armed with a Henry rifle was the equivalent of 14 or 15 men equipped with single-shot guns.[6]

Henry's rifle was probably used in the January Uprising by Count Jan Kanty Dzialynski in the Battle of Ignacew. In the memoirs from the epoch, it is reported that Dzialynski was shooting from a 16-shot rifle during the battle. Another user of Henry's rifle in the January Uprising was Paul Garnier d'Aubin, officer of the French 23rd Infantry Regiment.

Operation

The Henry rifle used a .44 caliber cartridge with 26 to 28 grains (1.7 to 1.8 g) of black powder.[9] This gave it significantly lower muzzle velocity and energy than other repeaters of the era, such as the Spencer. The lever action, on the down-stroke, ejected the spent cartridge from the chamber and cocked the hammer. A spring in the magazine forced the next round into the follower; locking the lever back into position pushed the new cartridge into the chamber and closed the breech. As designed, the Henry lacked any form of safety. When not in use its hammer rested on the cartridge rim; any impact on the back of the exposed hammer could cause a chambered round to fire. If left cocked, it was in the firing position without a safety. Modern Henry replicas incorporate a safety mechanism, such as a transfer bar safety, so the gun will not fire if dropped or the hammer is released partially by accident.[10]

To load the magazine, the shooter moves the cartridge-follower along the slot into the top portion of the magazine-tube and pivots it to the right to open the front-end of the magazine. He loads up to 15 cartridges one by one, he pivots the top portion back and releases the follower.

Legacy

While never issued on a large scale, the Henry rifle demonstrated its advantages of rapid fire at close range several times in the Civil War and later during the wars between the United States and the Plains Indians. Examples include the successes of two Henry-armed Union regiments at the Battle of Franklin against large Confederate attacks, as well as the Henry-armed Sioux and Cheyenne's destruction of the 7th Cavalry at Little Big Horn.

Manufactured by the New Haven Arms Company, the Henry rifle evolved into the famous Winchester Model 1866 lever-action rifle. With the introduction of the new Model 1866, the New Haven Arms Company was renamed the Winchester Repeating Arms Company.

Reproductions

The unrelated Henry Repeating Arms produces a replica of the Model 1860 Henry Rifle with brass receiver and American walnut stock, but a modern steel barrel and internal components.[11]

Uberti produces an almost exact copy Henry Model 1860 chambered in .44-40 Winchester or .45 Colt, rather than the original .44 Henry rimfire. Distributed by several companies, these replicas are popular among Cowboy Action Shooters and Civil War reenactors, as well as competition shooters in the North-South Skirmish Association(N-SSA).[12]

Gallery

- Civil War 1860 Henry rifle

- Henry rifle, receiver

- Henry rifle, loading-lever, toggle-joint

- 1860 Henry and 1866 Winchester Musket

Modern replica Henry rifle

Modern replica Henry rifle

See also

References

Notes

- Tales of the Gun: Guns of the Civil War. (12:34 — 12:40) History Channel, 2001.

- Butler, David F. United States Firearms The First Century 1776-1875 (New York: Winchester Press, 1971), p.229.

- Butler, p. 226.

- Butler, p.233.

- Butler, p. 232.

- Tales of the Gun: Guns of Winchester. (21:12 — 21:58) History Channel, 2001.

- http://www.henryrepeating.com/history.cfm

- Bresnan, Andrew L. "Chapter 7: The 'Modern Henry'". The Henry Repeating Rifle: Victory thru rapid fire. rarewinchesters.com. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- Bresnan, Andrew L. "Introduction". The Henry Repeating Rifle: Victory thru rapid fire. rarewinchesters.com. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- Bresnan, jack L. "Chapter 6: Henry Odds and Ends". The Henry Repeating Rifle: Victory thru rapid fire. rarewinchesters.com. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- Staff (January 2014). "Henry Repeating Arms Co. Expands line and capacity". American Rifleman. 162 (1): 32.

- NSSA Approved Arms page. Archived March 5, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

Bibliography

- Hartford Michigan Military History.

- American Rifleman, May 2008; (Henry Repeating Arms) founder, p. 26.

- Sword, Wiley. The Historic Henry Rifle: Oliver Winchester's Famous Civil War Repeater. Lincoln, Rhode Island : Andrew Mowbray Publishers, 2002.

- Compared: .357 Mag. Henry Big Boy, Marlin 1894C and Uberti 1873 Rifles by Chuck Hawks.