Henry Rich, 1st Earl of Holland

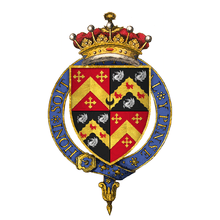

Henry Rich, 1st Earl of Holland KG KB PC (19 August 1590 (baptised) – 9 March 1649), known as Lord Kensington between 1623 and 1624, a member of the influential Rich family, was an English courtier, peer and soldier.

Origins

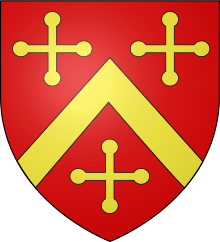

He was the second son of Robert Rich, 1st Earl of Warwick (1559-1619) by his first wife Penelope Devereux. His elder brother was Robert Rich, 2nd Earl of Warwick (1587–1658).

Career

He began his career as a courtier and soldier in 1610, swiftly becoming a favourite of King James I, but fell out of favour on the accession of Charles I. He was created Baron Kensington in 1622, and Earl of Holland in 1624.[1] He was one of the many lovers of Marie de Rohan, the veteran of French court intrigue.

Public Offices

He was elected a Member of Parliament for Leicester in 1610 and was re-elected in 1614, having failed to be elected for the prestigious county seat of Norfolk. He was appointed joint Lord Lieutenant of Berkshire for 1628–1632 and sole Lieutenant of that county for 1632–1643. He was also joint Lord Lieutenant of Middlesex for 1628–1642 and sole Lieutenant for 1642–1643.[2]

He served as Captain of the Yeomen of the Guard from 1617 to 1632, Master of the Horse in 1628, Constable of Windsor Castle from 1628 to 1648 and Chancellor of the University of Cambridge from 1628 until his death.[2]

Military career

During the Civil War, On Sunday 9 July 1648, seven months before the execution of King Charles I, the Earl and his army of approximately 400 men entered St Neots in the county of Huntingdonshire. The Earl's men were hungry and weary, following their escape from Kingston upon Thames, where the Parliamentary forces had completely overwhelmed them. Of his original army of 500, the Earl escaped with about 100 cavalry and was immediately followed by a small party of Puritan and Parliamentary cavalry. After much hesitation concerning which direction they should flee to, the Earl decided on Northampton, whither the group made their way via St Albans and Dunstable. At the outskirts of Bedford the group turned eastward towards the town of St Neots. At Kingston, the Earl was joined by the young George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, his young brother Francis Villiers and Henry Mordaunt, 2nd Earl of Peterborough. They were also joined by Colonel John Dalbier, an experienced German soldier who was hated by the Roundheads, having previously served with them under the Robert Devereux, 3rd Earl of Essex until he defected to the Royalist side.

The field officers of Holland's force sought only rest and safety. Colonel Dalbier called a council of war, at which many officers voted to disperse into the surrounding countryside. Others suggested they should continue northwards. Colonel Dalbier advised on the strategic position of St Neots and the fact that the joint remnants of the forces of Buckingham and Holland had increased sufficiently since the retreat from the Roundheads at Kingston. He suggested they should meet and engage their pursuers. He further added that, by obtaining a victory, the fortunes of war could be turned in their favour. Due to his vast experience as a soldier, his words were listened to with respect. He further offered to guard them through the night in case of a surprise attack, or to meet a soldier's death in the defence of the town. A vote was taken and Dalbier's plan was adopted.

The Earl of Holland, who it was said "had better faculty at public address than he had with a sword", joined Buckingham and Peterborough in addressing the principal residents and townsfolk of St Neots. The Duke of Buckingham spoke at length, claiming "they did not wish to continue a bloody war, but wanted only a settled government under Royal King Charles". Assurances were also given that their Royalist troop would not riot or damage the townfolks’ property. On the latter promise it is recorded that they were faithful to their word.

Fatigued by their battle and consequent retreat from Kingston, the field officers eagerly sought rest. True to his word, Colonel Dalbier kept watch over them. The small group of Puritan horsemen who had pursued them had, upon reaching Hertford, met with Colonel Adrian Scrope and his Roundhead troops from their detachment at Colchester.

At two o’clock on Monday morning, 10 July, 100 Dragoons from the Parliamentary forces arrived ahead of the main army at Eaton Ford. Dalbier was at once informed, and immediately gave the alarm: "To horse, to horse!" The Dragoons, equipped with musket and sword, crossed St Neots’ Bridge before the Royalists were fully prepared. The Battle of St Neots had begun.

Battle of St Neots

The few Royalists guarding the bridge quickly fell back from the superior numbers before them. The ensuing battle was now fought on the main square and streets of the town. The remaining Royalists were now fully prepared for combat. The main army of Roundheads had also arrived, and a further wave of Puritans crossed the bridge into town. The battle was fierce, with the Puritans gaining ground.

Colonel Dalbier died during the early stages of the battle. Other prominent Royalists, including Buckingham's younger brother Francis Villiers, and Kenelm Digby (son of the scientific writer of the same name), were also killed during the battle. Other officers and men drowned whilst attempting to escape by crossing the River Ouse. The young Duke of Buckingham, being overwhelmed by the speed of these events, escaped with 60 horsemen to Huntingdon, with the intention of continuing towards Lincolnshire. Upon realising the Roundheads were in hot pursuit, he changed plans, and via an evasive route returned to London from where he later escaped to France.

The Earl of Holland with his personal guard fought their way to the inn at which he had stayed the previous night. The gates had been closed and locked, but were quickly opened to admit him, and immediately closed again as he entered. The Parliamentarians soon battered them down and entered the inn. The door of the Earl's room was burst open to reveal him facing them, sword in hand. It is recorded that he offered surrender of himself, his army and the town of St Neots, on condition that his life was spared.

The Puritans seized the Earl and took him before Colonel Scroope, who ordered him to be shackled and imprisoned under guard. The remaining Royalist prisoners were locked in St Neots parish church overnight, then taken to Hitchin the following morning. The Earl and five other field officers were taken to Warwick Castle, which had remained a parliamentary stronghold throughout the war. They remained prisoners for the next six months, until their trial for high treason. In London it was said "His Lordship may spend time as well as he can and have leisure to repent his juvenile folly."

Peterborough also escaped disguised as a gentleman merchant, but was later recognised and arrested. Friends aided their escape again whilst en route to London for trial. He then stayed at various safe houses, financed by his mother, until he managed to flee the country.

Trial and execution

On 27 February 1649, the Earl of Holland was moved to London for trial. He pleaded his crime was not capital, and claimed that he had surrendered St Neots town on the condition that his life would be spared. It was stated at the time that in 1643, Lord Holland had been loyal to Parliament, but decided to change sides later that year and join the Royalists. He was with the King's forces at the Battle of Chalgrove, but stole away during a dark night before the close of battle.

On 3 March, the Earl was condemned as a traitor and sentenced to death. His brother, the Earl of Warwick, and sister-in-law the Countess of Warwick, petitioned Parliament for his life, as did other ladies of rank. The Puritan Parliament divided its vote equally. The speaker gave the casting vote for the sentence to stand. The petition had succeeded only in deferring the execution for two days. The Earl was dangerously ill during this period, and neither ate nor slept.

On the morning of his execution, 9 March, before Westminster Hall, the Earl walked unaided, but spoke to people along the way, declaring his surrender at St Neots was on condition that his life would be spared. At the scaffold he prayed, then gave the executioner his forgiveness and what money he still had on his person, which was approximately ten pounds. Upon laying his head on the block, he signalled the executioner by stretching his arms outwards. His head was severed in one stroke by the executioner's axe. Very little blood flowed, due to his weakness; the prevailing feeling was that, even had the execution not taken place, he probably would not have lived for very long anyhow.

The second rising of the English Civil War had culminated in the Battle of Preston during August 1648, with the Roundheads marching 250 miles in 26 days through foul weather and conditions, to defeat and ensure the Royalists would never re-form as an army.

The townspeople of St Neots, who apparently were neutral during the entire conflict, continued their peaceful existence.

Marriage and children

In 1616 the Earl married Isabel Cope, daughter, only child and sole heiress of Sir Walter Cope (c. 1553–1614) of Cope Castle in the parish of Kensington, Middlesex, by his wife Dorothy Grenville (1563–1638). Having inherited Cope Castle by marriage, Rich changed its name to Holland House, having been raised to the peerage as Baron Kensington in 1622, and Earl of Holland in 1624. By his wife he had at least six children, including:[3]

Sons

- Robert Rich, 2nd Earl of Holland, 5th Earl of Warwick (c. 1619 – 16 April 1675), eldest son and heir, who married firstly Lady Anne Montagu, his second cousin, daughter of Edward Montagu, 2nd Earl of Manchester; secondly, in 1641, Elizabeth Ingram, a daughter of Sir Arthur Ingram the younger of Temple Newsam, Yorkshire and his first wife Eleanor Slingsby. Upton, in the reference, is incorrect in naming the bride as daughter of Sir Arthur Ingram the elder.[4]

- Charles Rich (d. c. April 1645);

- Henry Rich (d. 1669);

- Cope Rich (christened 3 May 1635; buried 7 August 1676),[5] whose grandson was Edward Rich, 5th Earl of Holland, 8th Earl of Warwick (1695–1759).

Daughters

- Lady Dorothy Rich (27 September 1616 – c. December 1617);

- Lady Frances Rich (c. 1617 – 12 November 1672), married William Paget, 5th Baron Paget in 1632, and had issue;

- Lady Isabella Rich (christened 6 October 1623), married Sir James Thynne (d. 1670), died childless;

- Lady Susannah Rich (c. 1628 – 1649) (Countess of Suffolk), who on 1 December 1646[6] married (as his first wife) James Howard, 3rd Earl of Suffolk (1618/20 – 1689) and had surviving issue: one daughter Lady Essex Howard[7] through whom in 1784[8] the barony of Howard de Walden passed to her descendant John Griffin, 1st Baron Braybrooke, 4th Baron Howard de Walden (1719-1797), but fell into abeyance 1797. The barony of Braybrooke passed by special remainder to a relative; the Barony of Howard de Walden passed through Howard and then Hervey descent (via the 3rd Earl's granddaughter (by his second wife), Elizabeth Felton, Countess of Bristol[9] ).[10]

- Lady Diana Rich (d. 1658);

- Lady Mary Rich (c. 1636 – 8 February 1666), who in 1657 married (as his first wife) John Campbell of Glenorchy (from 1681 1st Earl of Breadalbane and Holland), son of Sir John Campbell of Glenorchy, 4th Baronet, by whom she had issue.[11] Lady Mary Rich was never Countess of Breadalbane and Holland, as she died before the title was gained by her husband (he was made a peer in 1677, and was given the earldom in 1681).

Notes

- Webb, E.A. (1921). "The parish: Descendants of Rich and the advowson". The records of St. Bartholomew's priory [and] St. Bartholomew the Great, West Smithfield. 2. pp. 292–296. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- Watson, Paula; Coates, Ben (2010). "Rich, Henry (1590-1649)". In Thrush, Andrew; Ferris, John P. (eds.). The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1604-1629. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107002258.

- A.F.Upton, Sir Arthur Ingram c 1565-1642 OUP 1961

- "Holland, Earl of (E, 1624 - 1759) Cracroft's Peerage, retrieved 25 November 2012

- Cracroft's Peerage says they married 1640

- thepeerage.com Lady Essex Howard

- thepeerage.com John Griffin Whitwell, 1st Baron Braybrooke

- thepeerage.com Elizabeth Felton, Countess of Bristol

- Suffolk, Earl of (E, 1603) Archived 25 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine and Howard de Walden, Baron (E, 1597) Cracroft's Peerage, retrieved 25 November 2012

- Breadalbane and Holland, Earl of (S, 1677 - dormant 1995) Archived 8 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Cracroft's Peerage, retrieved 25 November 2012

References

- . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- "Tudor Place Biography". Retrieved 27 December 2007.

Further reading

- Clarendon, Earl of (Edward Hyde), The History of the Rebellion and Civil Wars in England. Several volumes, depending on edition. A description of the events at St Neots, and Holland's subsequent imprisonment, appears in the 1840 edition (Oxford), vol. VI pp. 92–95.

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by The Viscount Fentoun |

Captain of the Yeomen of the Guard 1617–1632 |

Succeeded by The Viscount Dupplin |

| Preceded by The Duke of Buckingham |

Master of the Horse 1628 |

Succeeded by The Marquess of Hamilton |

| Preceded by The Earl of Banbury |

Lord Lieutenant of Berkshire 1628–1643 With: The Earl of Banbury 1628–1632 |

Succeeded by Interregnum |

| Preceded by The Duke of Buckingham |

Lord Lieutenant of Middlesex 1628–1643 With: The Earl of Dorset 1628–1642 |

Succeeded by Interregnum |

| Legal offices | ||

| Preceded by The Earl of Pembroke |

Justice in Eyre south of the Trent 1631–1649 |

Succeeded by Vacant |

| Parliament of England | ||

| Preceded by William Skipwith Henry Beaumont |

Member of Parliament for Leicester 1610–1621 With: Henry Beaumont 1610–1614, Francis Leigh 1614–1621 |

Succeeded by Sir Richard Moryson Sir William Herrick |

| Peerage of England | ||

| New creation | Earl of Holland 1624–1649 |

Succeeded by Robert Rich |

| Baron Kensington 1623–1649 | ||