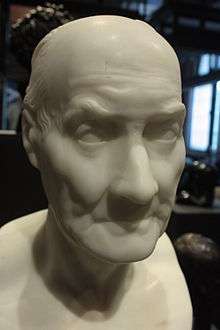

Henry Mackenzie

Henry Mackenzie FRSE (August 1745 – 14 January 1831 died at Edinburgh)[1] was a Scottish lawyer, novelist and writer. He was sometimes described as the Addison of the North. While Mackenzie is now mostly remembered as an author, his principal income came from legal roles, leading in 1804–1831 to a lucrative post as Comptroller of Taxes for Scotland, which allowed him to indulge his interest in writing.[2]

Biography

Mackenzie was born at Liberton Wynd in Edinburgh on 26 July 1745.[3] His father, Dr Joshua Mackenzie, was a distinguished Edinburgh physician[4] and his mother, Margaret Rose, belonged to an old Nairnshire family. Mackenzie's own family descended from the ancient Barons of Kintail through the Mackenzies of Inverlael.[5]

Mackenzie was educated at the High School and then studied Law at University of Edinburgh. He was then articled to George Inglis of Redhall (grandfather of John Alexander Inglis of Redhall), who was attorney for the crown in the management of exchequer business. Inglis had his Edinburgh office on Niddry Wynd, off the Royal Mile[6], a short distance from Mackenzie's family home.

In 1765 he was sent to London for his legal studies, and on his return to Edinburgh he set up his own legal office at Cowgatehead off the Grassmarket,[7] apparently as a partner with Inglis (but appearing in directories more as a rival), while he concurrently acted as attorney for the Crown.[8]

Mackenzie had tried for several years to interest publishers in what would become his first and most famous work, The Man of Feeling, but they would not accept it. Finally, Mackenzie published it anonymously in 1771, to instant success. The "Man of Feeling" is a weak creature, dominated by futile benevolence, who goes up to London and falls into the hands of those who exploit his innocence. The sentimental key in the book shows the author's acquaintance with Sterne and Richardson, but in Sir Walter Scott's summary assessment, his work lacked the story construction, humour and character of these writers.[9]

A clergyman from Bath named Eccles claimed authorship of the book, bringing in support for his pretensions a manuscript full of changes and erasures.[10] Mackenzie's name was then officially announced, but Eccles appears to have induced some people to believe him. In 1773 Mackenzie published a second novel, The Man of the World, whose hero was as consistently bad as the "Man of Feeling" had been "constantly obedient to every emotion of his moral sense," as Sir Walter Scott put it.[11] Julia de Roubigné (1777) is an epistolary novel.

The first of his dramatic pieces, The Prince of Tunis, was staged in Edinburgh in 1773 with some measure of success, but others were failures. In Edinburgh Mackenzie belonged to a literary club, at whose meetings papers in the manner of The Spectator were read. This led to the establishment of a weekly periodical, the Mirror (23 January 1779 – 27 May 1780), of which Mackenzie was editor and chief contributor. It was followed in 1785 by a similar paper, the Lounger, which ran for nearly two years and included one of the earliest tributes to the genius of Robert Burns.

In 1783 he was a joint founder of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, serving as its Literary President in 1812–1828 and its Vice President in 1828–1831.[12]

Mackenzie was an ardent Tory. He wrote many tracts intended to counteract doctrines of the French Revolution, contributing to the Edinburgh Herald under the pseudonym "Brutus".[13] Most of them remained anonymous, but he acknowledged his Review of the Principal Proceedings of the Parliament of 1784, a defence of the policy of William Pitt written at the desire of Henry Dundas. He was rewarded (1804) by the office of comptroller of the taxes for Scotland.

In 1776 Mackenzie married Penuel, daughter of Sir Ludovich Grant of Grant. They had eleven children. He was, in his later years, a notable figure in Edinburgh society. He was nicknamed the "man of feeling", but in reality he was a hard-headed man of affairs with a kindly heart. Some of his literary reminiscences appeared in his Account of the Life and Writings of John Home, Esq. (1822). He also wrote a Life of Doctor Blacklock, prefixed to the 1793 edition of the poet's works.

In 1807 The Works of Henry Mackenzie were published surreptitiously, and he then himself superintended the publication of his Works (8 vols., 1808). There is an admiring but discriminating criticism of his work in the Prefatory Memoir prefixed by Sir Walter Scott to an edition of his novels in Ballantyne's Novelist's Library (vol. v., 1823).

Family

Mackenzie's 1776 marriage to Penuel Grant,[14] daughter of Sir Ludovic Grant,[15] made him uncle by marriage to Lewis Grant-Ogilvy, 5th Earl of Seafield.[16] His eldest son, Joshua Henry Mackenzie (1777–1851) was a senator of the College of Justice known as Lord MacKenzie, buried with his father in Greyfriars Kirkyard.[17] Two other sons, Robert and William, worked for the East India Company. He also had two daughters, Margaret and Hope.[18] His nephew, Joshua Henry Davidson (1785–1847) was First Physician in Scotland to Queen Victoria.[19]

Death

Henry Mackenzie died on 14 January 1831, at home in the huge Georgian town house of 6 Heriot Row.[20] He is buried at Greyfriars Kirkyard, Edinburgh, in a grave facing north in the centre of the north retaining wall.

Freemasonry

MacKenzie was a Scottish Freemason. He was initiated into Lodge Canongate Kilwinning, No. 2, (Edinburgh, Scotland), on 2 December 1784.[21]

Works

- The Man of Feeling (1771)

- The Man of the World (1773)

- Julia de Roubigné (1777)

- The Prince of Tunis

- Review of the Principal Proceedings of the Parliament of 1784

- Account of the Life and Writings of John Home, Esq.

- Life of Doctor Blacklock

- In 1779/1780 he edited The Mirror and in 1785/1787 The Lounger.[22]

References

- The Century Cyclopaedia of Names (1894). p. 637.

- Drescher, H. W. (2004). "Mackenzie, Henry (1745–1831)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/17586. Retrieved 15 January 2016. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Monuments and monumental inscriptions in Scotland, The Grampian Society, 1871.

- Mackenzie, Alexander (1894). History of the Mackenzies. Inverness: A & W Mackenzie.

- Edinburgh and Leith Post Office Directory 1775–1776.

- Williamson's Directory 1775.

- Harold W. Thompson, A Scottish Man of Feeling (London: Oxford University Press, 1931), p. 81.

- Scott, Walter (1829). Henry Mackenzie (1824). Miscellaneous Prose Works. 3. pp. 209–221.

- Simon Stern, 'Sentimental Frauds,' Law & Social Inquiry 36 (2011): 83–113 (pp. 97–99).

- [Sir Walter Scott], "A Short Sketch of the Author's Life and Writings," in Henry Mackenzie, The Man of Feeling (London, 1806), iv, rpt in Scott, Miscellaneous Prose Works (Edinburgh: Cadell, 1847), 1: p. 344.

- Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. 2006. ISBN 0-902-198-84-X.

- Harris, Bob. "Scotland's Newspapers, the French Revolution and Domestic Radicalism (c. 1789–1794)". Scottish Historical Review. 84 (1): 49. doi:10.3366/shr.2005.84.1.38. ISSN 0036-9241 – via Edinburgh University Press.

- Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 0-902-198-84-X.

- Monuments and monumental inscriptions in Scotland: The Grampian Society, 1871.

- Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- History of the Lodge Canongate Kilwinning, No. 2, compiled from the records 1677–1888 by Alan MacKenzie, 1888. p. 243.

- Monuments and monumental inscriptions in Scotland, The Grampian Society, 1871.

- Gale Group – Eighteenth-Century Collections Online

- British Authors Before 1800: A Biographical Dictionary, edited by Stanley J. Kunitz and Howard Haycraft, New York, the H. W. Wilson Company, 1952.