Headless men

Various species of mythical headless men were rumored, in antiquity and later, to inhabit remote parts of the world. They are variously known as akephaloi (Greek ἀκέφαλοι, "headless ones") or Blemmyes (Latin: Blemmyae; Greek: βλέμμυες) and described as lacking a head, with their facial features on their chest. These were at first described as inhabitants of the Nile system (Aethiopia). Later traditions confined their habitat to a particular island in the Brison(e) River,[lower-alpha 1] or shifted it to India.

Blemmyes are said to occur in two types: with eyes on the chest or with the eyes on the shoulders. Epiphagi, a variant name for the headless people of the Brisone, is sometimes used as a term referring strictly to the eyes-on-the-shoulders type.

Etymology

Various etymologies had been proposed for the origins of the name "Blemmyes", and the question is considered unsettled.[1]

In antiquity, the actual tribe known as the Blemmyes were said to be named eponymously after King Blemys (Βλέμυς), according to Nonnus's 5th century epic Dionysiaca, but no lore about headlessness is attached to the people in this work.[2][3] Samuel Bochart of the 17th century derived the word Blemmyes from the Hebrew bly (בלי) "without" and moach (מוח) "brain", implying that the Blemmyes were people without brains (although not necessarily without heads).[4][5] A Greek derivation from blemma (Greek: βλέμμα) "look, glance" and muō (Greek: μύω) "close the eyes" has also been suggested.[6] Wolfgang Helck claimed a Coptic word "blind" for its etymology.[7]

Leo Reinisch in 1895 proposed that it derived from bálami "desert people" in the Bedauye tongue (Beja language). Although this theory had long been neglected,[8] this etymology has come into acceptance, alongside the identification of the Beja people as true descendants of the Blemmyes of yore.[9][10][11]

In antiquity

The first indirect reference to the Blemmyes occurs in Herodotus, Histories, where he calls them the akephaloi (Greek: ἀκέφαλοι "without a head").[12] The headless akephaloi, the dog-headed cynocephali, "and the wild men and women, besides many other creatures not fabulous" dwelled in the eastern edge of ancient Libya, according to Herodotus's Libyan sources.[13]

Mela was the first to name the "Blemyae" of Africa as being headless with their face buried in their chest.[14] In a similar vein, Pliny the Elder in the Natural History reports the Blemmyae tribe of North Africa as "[having] no heads, their mouths and eyes being seated in their breasts".[15] Pliny situates the Blemmyae somewhere in Aethiopia (in, or in the neighboring lands to Nubia).[lower-alpha 2][15][16][17] Modern commentators on Pliny have suggested the notion of headlessness among Blemmyes may be due to their combat tactic of keeping their heads pressed close to the chest, while half-squatting with one knee to the ground.[lower-alpha 3][5][18] Solinus adds they are believed to be born with their head part dismembered, their mouth and eyes deposited on the breast.[19]

The term acephalous (akephaloi) was applied to people without heads whose facial parts such as eyes and mouth have relocated to other parts of the body, and the Blemmyes as described by Pliny or Solinus conform with this appellation.[20]

In the Chinese classic text Classic of Mountains and Seas, the god Xingtian is described as having no head, and with his nipples as eyes and his belly button as a mouth. This is because he got decapitated in a battle against Huangdi.

Middle Ages

By the 7th or 8th century there had been composed a Letter of Pharasmenes to Hadrian,[lower-alpha 4] whose accounts of marvels such as bearded women (and headless men) became incorporated into later texts. This included De Rebus in Oriente mirabilibus (also known as Mirabilia), its Anglo-Saxon translation, Gervase of Tilbury's treatise, and the Alexander legend attributed to Leo Archipresbyter.[21]

The Latin text in the recension known as the Fermes Letter[lower-alpha 5] was translated verbatim in Gervase of Tilbury's Otia Imperialia (ca. 1211) which describes a "people without heads" ("Des hommes sanz testes") of a golden color, measuring 12 feet tall and 7 feet wide, living on an isle in the River Brisone (in Ethiopia).[lower-alpha 6][24][25]

The catalogue of strange peoples from Letter occur in the Anglo-Saxon Wonders of the East (translation of Mirabilia) and the Liber Monstrorum; recensions of both these works are bound in the Beowulf manuscript.[26][22] The transmission is imperfect. No name is given to the headless islanders, eight feet tall in the Wonders of the East.[lower-alpha 7][27][28] Epiphagi ("epifugi") is the name of the headless in Liber Monstrorum.[lower-alpha 8][29] This form derives from "epiphagos" in a modified recension of the Letter of Pharasmenes known as the Letter of Premonis to Trajan (Epistola Premonis Regis ad Trajanum).[lower-alpha 9][31]

Alexander romances

—Hisotria de preliis in French, BL Royal MS 15 E vi, c. 1445.

The Letter material was incorporated into the Alexander legend by Leo Archipresbyter, known as Historia de Preliis (version J2),[32] which was translated into Old French as Roman d'Alexandre en prose. In the prose Alexandre the golden-colored headless encountered by Alexandre measured just 6 feet tall, and had beards reaching their knees.[33][19] In the French version, Alexander captures 30 of the headless to show the rest of the world, an element lacking in the Latin original.[34]

Other Alexander books that contain the headless people episode are Thomas de Kent's romance and Jean Wauquelin's chronicle.[35][36]

Medieval maps

The blemmyes or the headless people have also been illustrated and described on medieval maps. The Hereford Mappa Mundi (ca. 1300) places the "Blemee" in Ethiopia (upper Nile system), deriving its information from Solinus, perhaps via Isidore of Seville.

One Blemee standing has his face on their chest, and another below him has "eyes and mouth at their shoulders". Both varieties of Blemmyae occur according to Isidore,[lower-alpha 10][37][38] who reported that in Libya, besides the Blemmyae born with a face on the chest, there were reputedly "others, born without necks, [and] have their eyes on their shoulders".[39] Some modern commentators believe the two different types represent the male and female blemmyes, with their genitals explicitly drawn.[40][41] Another example is the Ranulf Higden map (ca. 1363), which bears an inscription regarding the headless in Ethiopia, although unaccompanied by any picture of the people.[lower-alpha 11][42]

—Andrea Bianco map (1436)

By the Late Middle Ages, world maps began to appear that located the headless people further east, in Asia, such as the Andrea Bianco map (1436) that depicted people who "all do not have heads (omines qui non abent capites)" in India, on the same peninsula as the terrestrial paradise.[lower-alpha 12] But other maps of the period such as the Andreas Walsperger's map (ca. 1448) did continue to locate the headless in Ethiopia.[lower-alpha 13][44][45] The post-medieval map of Guillaume Le Testu (pictured above) illustrates the headless and the dog-headed cynocephali north beyond the Himalayan mountains.[46]

Late Middle Ages

The Travels of Sir John Mandeville writes of "ugly folk without heads, who have eyes in each shoulder" with their mouths "round like a horseshoe, in the middle of their chest" living among the populace in the big island of Dundeya (Andaman Islands) between India and Myanmar. In other parts of the island are headless men with eyes and mouth on their backs.[47] This has been noted as an example of Blemmyes by commentators,[48][49] though Mandeville does not use the term.

.jpg)

Examples of chapters on monstrous races (including the headless), taken from earlier sources, occur in the Buch der Natur or the Nuremberg Chronicle[50]

The Buch der Natur (ca. 1349), written by Conrad of Megenberg, described the "people without heads (läut an haupt)"[lower-alpha 14] as shaggy all over the body, with "coarse hair like wild animals",[lower-alpha 15] but when the printed book versions appeared, their woodcut illustrations depicted them as smooth-bodied, in contradiction to the text.[51] Conrad lumped peoples of various geography under "wundermenschen", and condemned such wondrous people as earning physical deformities due to the sins of their ancestors.[lower-alpha 16][52]

Age of Discovery

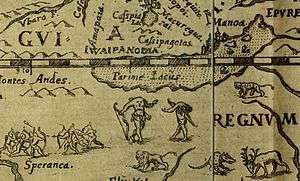

During the Age of Discovery, a rumor of headless men called the Ewaipanoma was reported by Sir Walter Raleigh in his Discovery of Guiana, to have been living on the banks of the Caura River. Of the story, Raleigh was "resolved it is true, because every child in the provinces of Aromaia and Canuri affirm the same". He also cited an anonymous Spaniard's sighting of the Ewaipanoma.[53] Joannes de Laet, a somewhat later contemporary, dismissed the story, writing that these natives' heads were set so close to the shoulders that some were led to believe their eyes were attached to the shoulders and the mouth to their breasts.[20]

During the same period (around 1589–1600) another English writer, Richard Hakluyt, described a voyage by John Lok to Guinea, where he found "people without heads, called Blemines, having their eyes and mouth in their breast."[54] The authorship of the report is ambiguous.[55]

The commonalities between Raleigh and Hakluyt writings might suggest the existence of an urban legend at that time, since both were English writers, writing during the same period, about trips to different continents (Africa and Latin America).

Ewaipanomas were depicted on numerous later maps using Raleigh's account as a reference. Jodocus Hondius included them in his 1598 chart of Guyana and in a display various Amerindian peoples in a map of North America released in the same year. Cornelis Claesz, who had worked alongside Hondius on numerous occasions, reproduced this display in a 1602 map of the Americas, but modified the Ewaipanoma to possess a true head but lack a neck, setting the figure's head at the level of the shoulders. Ewaipanomas began to decrease in popularity as a cartographic motif after this point; Hondius' 1608 world map does not include them, but merely notes that headless men are reported in Guyana while casting doubt on the veracity of these claims. Pieter van den Keere's 1619 world map, which includes a Claesz-like neckless figure in a display of Amerindian tribesmen, is the last to depict Ewaipanomas.[56]

Modern rational explanations

Explanations similar to de Laet's were repeated in later years. In the Age of Enlightenment, Joseph-François Lafitau asserted that while "acephalous" races were actually present in North America, they were no more than a local trait of having the head set deep in the shoulders. He argued that reports of "headless" traits in the "East Indies" by writers of antiquity is evidence that people of the same genetic pool migrated from Asia to North America.[57] Contemporary literature say certain writers attribute Blemmyes' physique as an ability to raise both shoulders to an extraordinary height, and ensconcing their head in between.[4]

Other explanations have been offered for the legend of their unusual physique. As noted earlier, native warriors perhaps employed the tactic of keeping head tucked close to the breast while marching with one knee on the ground.[18] Or, perhaps, they had the custom of carrying shields ornamented with faces.[58]

Europeans also formerly considered Blemmyes to be an exaggerated report about apes.[59]

In art

Likenesses of blemmyes are used as supports for misericords at Norwich Cathedral and Ripon Cathedral, from earlier local folklore.[60] Writer Lewis Carroll is said to have invented characters based on objects in the Ripon church where his father served as canon, and in particular, the blemmyes here inspired his Humpty Dumpty character.[61]

In literature

They were mentioned vastly in Rick Riordan's Trials Of Apollo: The Dark Prophecy as Commodus's goons and bodyguards

"And of the Cannibals that each other eat, The Anthropophagi, and men whose heads Do grow beneath their shoulders." – Shakespeare, Othello [I.iii.143-144] (circa 1603).

In The Tempest, Gonzalo admittedly believed when he was young "that there were such men whose heads stood in their breasts". [III. iii. 46]

In Umberto Eco's Baudolino, the protagonist meets Blemmyes along with Sciapods and a number of monsters from the medieval bestiary in his quest to find Prester John.[62]

In his 2006 book La Torre della Solitudine, Valerio Massimo Manfredi features the Blemmyes as fierce, sand-dwelling creatures located in the southeastern Sahara, and suggests that they are the manifestation of the evil face of mankind.

Science fiction author Bruce Sterling wrote a short story entitled "The Blemmye's Stratagem", included in his collection "Visionary in Residence". The story describes a Blemmye during the Crusades, who turns out to be an extraterrestrial. Sterling later stated that the idea for his story was taken from a children's story by Waleed Ali.

Gene Wolfe writes of a man with his face on his chest, located in his short story collection Endangered Species.

Blemmyes appear in the 2000 novel The Amazing Voyage of Azzam by K Godel as cannibalistic tribesmen who guard a lost treasure of King Solomon. They use clubs, spears, and blow darts as weapons.

In music

The Australian band King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard mention "men whose heads do grow beneath their shoulders" in the track "Castle in the Air", on the album Polygondwanaland. This is a reference to Othello [I.iii.143-144]. Blemmyes also appear on the left of the album's cover art.

Gallery

Blemee on the Hereford Mappa Mundi (detail, Nile system)

Blemee on the Hereford Mappa Mundi (detail, Nile system) 13th-century bestiary leaf

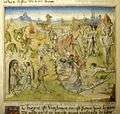

13th-century bestiary leaf Wondrous people of Ethiopia, 1377 manuscript of Secrets de l'histoire naturelle

Wondrous people of Ethiopia, 1377 manuscript of Secrets de l'histoire naturelle Wondrous people of Ethiopia, ca. 1460 Livres des Merveilles du Monde

Wondrous people of Ethiopia, ca. 1460 Livres des Merveilles du Monde

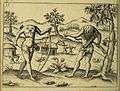

Headless from 1599 engraving in Sir Walter Raleigh's The Discovery of Guiana

Headless from 1599 engraving in Sir Walter Raleigh's The Discovery of Guiana

See also

- Acephaly

- Anthropophage

- Blemmyes

- Coluinn gunn cheann - Scottish headless monster (Popular Tales of the West Highlands)

- Headless Horseman

- Hitmonlee

- Kabandha

- Mapinguari

- Xing Tian

Explanatory notes

- Also "Brixonte[s]", etc.

- From the geographical description this was a desert area south and east of Egypt, between tributaries of the Nile, in Nubian-Egyptian border zone in the Eastern Desert.

- Comment by Louis Marcus (1829), taking hint from a passage in Heliodorus of Emesa Aethiopica Book V.

- Particularly the F-group of text known as Fermes Letter, represented in Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, nouv. acq. lat. 1065.

- Fermes Letter: "Est namque et alia insula in Brisone flumine, ubi nascuntur homines sine capite, habentes oculos et os in pectore; longi sunt pedes XII, lati et vasti pedes VII, colore et corpus auro simile".[22]

- River Brisone was a fictitious distributary of the Nile. Commentators (Gervase, Gerner & Pignatelli tr 2006, pp. 298, 536) localize the Brison as being in Ethiopia.

- Wonders says they live on "another island south of the Brixontes.." (Orchard tr.) presumably meaning another island in Brixontes River, but further south than the island where the donkey-eared, sheep-wooled, bird-footed animals called lertices dwell.

- Liber Monstrorum, I. 24: Epifugi, as the Greeks called them, are "eight feet tall and have all the functions of the head in their chests, except they are said to have eyes in their shoulders" (Orchard tr.); Latin text reads '..'quos Epifugos Graeci vocant et VIII pedum altitudinis sunt et tota in pectore capitis officia gerunt, nisi quod oculos in humeris habere dicuntur".

- XVII, 5 : est etiam in Brixonte insula in homines sine qua nascuntur captibus, quia in pectore et oculos habent in time, altitude novem pedum latitude et octo: hos epifagos vocamus.[30]

- Although Kline (2001) thinks the second type with eyes and mouth at shoulder should be identified as a "Epiphagi"

- Inscription reads "Gens ista habet caput et os in pectore" and can be read above the spine of the Atlas, to the far right on the image Ranulf Higden map

- Bianco locates the headless in the Orient, but the dog-heads still in Ethiopia.[43]

- Labeled "Hy haben vultum in pectore"

- Husband & Gilmore-House 1980, p. 47 refers to them as the "acephalous" but original German is followed here

- And having (sint über al rauch mit hertem hâr, sam diu wilden tier)"

- Thomas of Cantimpré, who was Conrad's primary source also associated the headless with sin, but allegorically. To Thomas the headless represented unscrupulous lawyers.[51]

References

- Zaborski (1989).

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca, XVII, 385–397

- Derrett (2002), p. 468.

- Chambers, Ephraim, ed. (1728). "Blemmyes". Cyclopædia, or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. 1 (first ed.). James and John Knapton, et al. p. 107.

- Pliny (1829), Histoire naturelle, III, Ajasson, M. (tr.); Marcus, Louis (notes), C. L. F. Panckoucke, pp. 190–1

- Morié, Louis J. (1904), Les civilisations africaines: La Nubie (Éthiopie ancienne), 1, A. Challamel, p. 65

- Der Kleine Pauly I, 913, cited in Derrett 2002, p. 468

- Zaborski (1989), pp. 172–173.

- Mukarovsky, Hans G. (1987), "Reinisch and Some Problems of he Study of Beja Today", Leo Reinisch: Werk und Erbe, Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, p. 130 (125–139)

- Updegraff, Robert T. (1988) [1972], László Török, "The Blemmyes I: The Rise of the Blemmyes and the Roman Withdrawal from Nubia under Diocletian", ANRW, II (10.1), p. 55 (44–106)

- Fleming, Harold C. (1988), Ongota: A Decisive Language in African Prehistory, p. 149

- Derrett (2002), p. 467.

- Herodotus. The Histories. Trans. A. D. Godley. 4.191.

- Derrett (2002), p. 469.

- Pliny the Elder (1893). The Natural History. 1. Trans. John Bostock and H. T. Riley. George Bell & Sons. p. 405. (Book 5.8)

- Pliny, Bostock & Riley (tr.) 1893, p. 405, note 1 (Book 5.8, note 9)

- Török, László (2009), Between Two Worlds: The Frontier Region Between Ancient Nubia and Egypt, BRILL, pp. 9–10, ISBN 9789004171978

- Pliny, Bostock & Riley (tr.) 1893, p.406, note 3 (Book 5.8, note 17)

- Druce (1915), pp. 137–139.

- "Acephaous". Encyclopædia Britannica. 1. 1823. pp. 130–131.

- Ford (2015), pp. 12–15; notes 23, 32.

- Stella (2012), p. 75.

- Ford (2015), p. 13, note 32.

- Gervase, in his autograph manuscript (Rome, Vat. Lat. 933) admits to using the Letter as his source.[23]

- Gervase of Tilbury (2006), Gerner, Dominique; Pignatelli, Cinzia (eds.), Les traductions françaises des Otia imperialia de Gervais de Tilbury, Droz, LXXV (p. 301)

- Oswald, Dana (2010), Monsters, Gender and Sexuality in Medieval English Literature, Boydell & Brewer

- Orchard, Andy (2003b). A Critical Companion to Beowulf. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. p. 24. ISBN 9781843840299.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Orchard 2003a, Wonders of the East, §15 (pp. 192–193)

- Orchard 2003a, Liber Monstrorum, I. 24 (p. 273)

- Stella (2012), p. 62, note 55.

- Stella (2012), pp. 62–63.

- Ford (2015), p. 12, note 23.

- Hilka, Alfons (1920), "Comment Alixandres trouva gens sans testes qui avoient couleur d'or et orent les iols on pis", Der Altfranzösische Prosa-Alexander-roman nach der Berliner Bilderhandschrift, nebst dem lateinischen Original der Historia de preliis, Max Niemeyer, p. 236

- Pérez-Simon, Maud (2014), Conquête du monde, enquête sur l'autre et quête de soi. Alexandre le Grand au Moyen Âge, Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l'homme, p. 204 (Open edition)

- Harf-Lancner, Laurence (2012), Maddox, Donald; Sturm-Maddox, Sara (eds.), "From Alexander to Marco Polo, from Text to Image: The Marvels of India", Medieval French Alexander, SUNY Press, p. 238

- Hériché, Sandrine (2008), Alexandre le Bourguignon: étude du roman Les faicts et les conquestes d'Alexandre le Grand de Jehan Wauquelin, Droz, pp. cxlvi, 233–234

- Kline, Naomi Reed (2001), Maps of Medieval Thought: The Hereford Paradigm, Boydell Press, pp. 143, 148–151

- Bevan, William Latham; Phillott, Henry Wright (1873), Mediæval Geography: An Essay in Illustration of the Hereford Mappa Mundi, E. Stanford, p. 103

- Isidore of Seville (2005), Throop, Priscilla (ed.), Isidore of Seville's Etymologies: Complete English Translation, Lulu.com, XI. 3. 17

- Westrem ed., Hereford Mappa Mundi, p. 381, item 971, 973; cited in Derrett 2002, p. 470

- Baumgärtner, Ingrid (2006), "Biblical, Mythical, and Foreign Women in the Texts and Pictures on Medieval World Maps" (PDF), The Hereford World Map: Medieval World Maps and their Context, British Library, p. 305

- Miller (1895), III, p. 105.

- Hoogvliet, Margriet (2007), Mappae mundi, Brepols, p. 211, ISBN 2503520650

- Miller (1895), III, p. 148.

- Hallberg, Ivar (1907), L'extrême orient dans la littérature et la cartographie de l'occident des XIIIe, XIVe, et XVe siècles : étude sur l'histoire de la géographie, Göteborg: Wald. Zachrisson, Blemmyis (pp. 78–79), archived from the original on 2009

- White, David Gordon (1991), Myths of the Dog-Man, University of Chicago Press, p. 86

- Moseley, C. W. R. D. (tr.) (2005) [1983], The Travels of Sir John Mandeville, Penguin, p. 29; 137, ISBN 978-0141902814

- Moseley 2005, p. 29

- Strickland, Debra Higgs (2003), Saracens, Demons, & Jews: Making Monsters in Medieval Art, Princeton University Press, p. 203

- Husband, Timothy; Gilmore-House, Gloria (1980), The Wild Man: Medieval Myth and Symbolism, Susan E. Tholl, Metropolitan Museum of Art, p. 6

- Husband & Gilmore-House (1980), p. 47.

- Metzler, Irina (2016), Fools and idiots?: Intellectual disability in the Middle Ages, Oxford University Press, p. 75

- Walter Raleigh (2006). The Discovery of Guiana. Project Gutenberg.

- Hakluyt, Richard (1598–1600). The principal navigations, voyages, traffiques & discoveries of the English nation, made by sea or over-land to the remote and farthest distant quarters of the earth at any time within the compass of these 1600 yeeres. p. 169.CS1 maint: date format (link)

- De Medici, Marie (April 27, 2017). "Africa — The Second Voyage to Guinea Set out by Sir George Barne, Sir Iohn Yorke, Thomas Lok, Anthonie Hickman and Edward Castelin, in the yere 1554. The Captaine whereof was M. Iohn Lok". Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- Surekha Davies (2016). Renaissance Ethnography and the Invention of the Human. Cambridge University Press.

- Delon, Michel (2013), Encyclopedia of the Enlightenment, London and New York: Routledge, Monster (p. 849), ISBN 9781135959982

- Friedman, John (2000) [1981], The Monstrous Races In Medieval Art and Thought, Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, pp. 12, 15, 25, 146, 178–179, ISBN 9780802071736

- Burton, Sir Richard Francis (1872), Zanzibar: City, Island, and Coast, 2, London: Tinsley brothers, p. 123

- Tasker, Edward G. (1993), Encyclopedia of Medieval Church Art, B.T. Batsford, blemya (p. 24)

- Derrett (2002), p. 466.

- Stella (2012), p. 39.

Bibliography

- Derrett, J. Duncan M. (2002), "A Blemmya in India", Numen, 49 (2): 460–474, JSTOR 3270598

- Druce, G. C. (1915), "Some Abnormal and Composite Human Forms in English Church Architecture", The Archaeological Journal, 72: 137–139

- Ford, A.J. (2015), Marvel and Artefact: The 'Wonders of the East' in its manuscript contexts, BRILL, pp. 12–15, notes 23, 32

- Miller, Konrad (1895), Mappaemundi: die ältesten Weltkarten, III, J. Roth, p. 144

- Orchard, Andy (tr.), ed. (2003a). Pride and Prodigies: Studies in the Monsters of the Beowulf Manuscript. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9780802085832.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stella, Francisco (2012), "Ludibria sibi, nobis miracula. La fortuna medievale delle scienza pliniana e l'antropologia della diversitas", La 'Naturalis Historia' di Plinio, Cacucci Editore S.a.s., p. 75 (39–75)

- Zaborski, Andrzej (1989), "The Problem of Blemmyes-Beja:An Etymolgy", Beiträge zur Sudanforschung, 4: 160–177