Haumia-tiketike

Haumia-tiketike (also Haumia-roa, Haumia-tikitiki, and simply Haumia) is the god of all uncultivated vegetative food in Māori mythology.[1][2] He is particularly associated with the starchy rhizome of the Pteridium esculentum,[3][4][5][lower-alpha 1] which became a major element of the Māori diet in former times.[6][7] He contrasts with Rongo, the god of kūmara and all cultivated food plants.

| Haumia-tiketike | |

|---|---|

Atua of all wild food plants | |

| Other names | Haumia, Haumia-roa, Haumia-tikitiki |

| Gender | Male |

| Region | New Zealand |

| Ethnic group | Māori |

| Personal information | |

| Parents | Rangi and Papa (Arawa) Tamanuiaraki (Kāi Tahu) |

| Siblings | Rongo-mā-Tāne, Tāne, Tangaroa, Tāwhirimātea, Tū (Arawa) Manuika, Manunuiakahoe, Huawaiwai, Tahitokuru, Kohurere, Teaohiawe, Haere, Uenukupokaia, Uenukuhorea, Rakiwhitikina, Te Pukitonga (Kāi Tahu) |

| Offspring | Te Mōnehu |

In different tribal and regional variations of the stories involving him, he is often a son or grandson of Ranginui (known as Rakinui near Southland and Otago). He is most commonly associated with Arawa traditions.

The name Haumia also belongs to a taniwha from the Manukau Harbour,[5][8] or the Waikato River.[9] There is yet another Haumia recorded as the ancestress of Paikea.[5] A fourth Haumia is the ancestor to Ngāti Haumia, a hapū of Ngāti Toa (not to be confused with the Ngāti Haumia hapū from Taranaki).[10]

Separation of the primordial parents

In the Arawa traditions of New Zealand's creation story, Haumia was the third child to attempt the forced separation of his parents Rangi and Papa to allow light and space into the world between them.[3] Despite Tāne being the one to successfully carry out the task, Haumia's involvement meant he was subjected to the fury of their brother Tāwhirimātea, god of winds and storms, who would have killed him if their mother had not hidden him and their brother Rongo-mā-Tāne under her bosom - that is, in the ground.[2][11]

While they had successfully escaped Tāwhirimātea's stormy wrath, they were later discovered by Tūmatauenga (god of war, here representing humankind) who felt betrayed that he was left to fend against Tāwhirimātea by himself, so when he saw Rongo-mā-Tāne's and Haumia-tiketike's hair and descendants (all represented by leaves) sticking up out of the earth he harvested them with a wooden hoe and devoured them in revenge.[2][5][6][11] (Orbell 1998:29).

Genealogy

Many of these relatives may not be considered atua as gods or greater spirits themselves but may instead be atua as lesser spirits. The translations of their names represent abstract concepts and aspects of nature, not unlike polytheistic deities.

Parentage

- Haumia-tiketike is a son of Ranginui and Papatūānuku,[5] according to the tribes of the Arawa waka.

- Elsdon Best noted that Haumia-tiketike was not recognised as a son of Ranginui and Papatūānuku by the tribes of the Tākitimu waka.[6]

- In Kāi Tahu traditions, Haumia-tiketike is a son of Tamanuiaraki ('Great son of heaven'), who is a son of Rakinui and Hekehekeipapa[5] ('Descend at the world').[4]

- In the southern Bay of Plenty and parts of the east coast Haumia-tiketike is a son of Tāne-mahuta, who is the son of Ranginui and Papatūānuku (Orbell 1998:29). This is an area of origin for most Tākitimu tribes.

Siblings

Arawa

- Rongo-mā-Tāne, god of cultivated foods, particularly kūmara.

- Tāne-mahuta, god of forests and birds.

- Tangaroa, god of the sea and fish.

- Tāwhirimātea, god of storms and violent weather.

- Tūmatauenga, god of war, hunting, cooking, fishing, and food cultivation.

Ngāi Tahu

In Kāi Tahu's traditions and likely those of other Tākitimu tribes, gods typically considered as Haumia-tiketike's brothers such as Rongo-mā-Tāne and Tāne-mahuta are instead his uncles or half-uncles.

Haumia-tiketike being listed first, Tamanuiaraki's other offspring included:

- Manuika ('Bird fish')

- Manunuiakahoe ('Power/Shelter of the rowers')

- Huawaiwai ('Pulpy fruit')

- Tahitokuru ('Ancient blow')

- Kohurere ('Flying mist')

- Teaohiawe ('Gloom day')

- Haere ('Go/Proceed')

- Uenukupokaia ('Trembling earth, go all around/encircle')

- Uenukuhorea ('Trembling earth, bald')

- Rakiwhitikina ('Heaven encircled with a belt')

- Te Pukitonga ('The fountain/origin at the south')

John White adds at the end of the listed children of Raki and Hekehekeipapa; "and so on to the generation of men now living."[4]

As an element of one Ngāi Tahu creation story of the South Island, Mount Brewster of the Southern Alps may be identified as being a frozen Haumia-tiketike,[12] therefore making him one of Aoraki's brothers turned to stone when their waka (the South Island) capsized.

God of uncultivated food plants

Bracken

Food-quality rhizomes (aruhe) were only obtained from the Pteridium esculentum bracken (rarauhe) growing in deep, moderately fertile soils. Bracken became abundant after the arrival of Māori, "mainly a result of burning to create open landscapes for access and ease of travel" (McGlone et al., 2005:1). Rhizomes were dug in early summer and then dried for use in the winter. Although it was not liked as much as kumara, it was appreciated for its ready availability and the ease with which it could be stored (Orbell 1998:29).

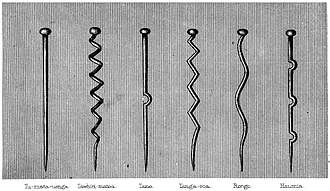

The rhizomes were air-dried so that they could be stored and become lighter. When ready for consumption, they were briefly heated and then softened with a patu aruhe (rhizome pounder); the starch could then be sucked from the fibres, or collected to be prepared for a larger feast. Several distinct styles of Patu aruhe were developed.

The plants of the bracken genus (Pteridium) contain the known carcinogen ptaquiloside,[15] identified to be responsible for haemorrhagic disease, as well as esophageal cancer, and gastric cancer in humans.

Other plants

A handful of other native plants from across New Zealand that are recorded as traditionally being used for food by Māori include:

- Cordyline australis - Tīkōuka, the shoots and roots could be cooked and eaten, or used to make a sweet beverage.[16]

- Coriaria arborea - Tutu, the juices were extracted from the berries and petals, and could be used to sweeten fernroot, or boiled with seaweed to make a black jelly.[17]

- Cyathodes juniperina - Mingimingi, edible berries.

- Dacrycarpus dacrydioides - Kahikatea, edible berries, and could apparently be used to make beer.

- Dacrydium cupressinum - Rimu, edible berries.

- Gaultheria antipoda - Tāwiniwini, edible berries.

- Leucopogon fasciculatus - Mingimingi, edible berries.

- Lobelia angulata - Pānakenake, the leaves were cooked and eaten as greens.

- Metrosideros excelsa - Pōhutukawa, a thin layer of honey was collected from the flowers.

- Muehlenbeckia australis - Puka, edible berries.

See also

- Family tree of the Māori gods

- Haumea, a Hawaiian goddess of fertility and childbirth

Notes

- Elsdon Best in his book, Maori Religion and Mythology Part 1, wrote that the Māori ate the rhizomes of Pteris aquilina,[6] which is Pteridium aquilinum.

References

- "Māori Dictionary search results for 'Haumia-tiketike'". John C Moorfield. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- Edward Shortland (1856). Traditions and Superstitions of the New Zealanders. London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans & Roberts. pp. 59–60.

- George Grey (1854). Polynesian Mythology and Ancient Traditional History of the New Zealanders. Christchurch: Whitcombe and Tombs. p. 3.

- John White (1887). The Ancient History of the Maori, His Mythology and Traditions. Wellington: G. Didsbury, government printer. pp. 19–20.

- Edward Tregear (1891). The Maori-Polynesian Comparative Dictionary. Lambton Quay, Wellington: Lyon and Blair. p. 54.

- Elsdon Best (1924). Maori Religion and Mythology Part 1. Wellington: Dominion Museum. p. 184.

- "Māori Dictionary search results for 'rarauhe'". John C Moorfield. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- Edward Shortland (1856). Traditions and Superstitions of the New Zealanders. London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans & Roberts. pp. 76–77.

- George Graham (1946). The Journal of the Polynesian Society: Some Taniwha and Tupua. Auckland. pp. 33, 35, 37–38.

- "Ngāti Haumia (Ngāti Toa)". National Library of New Zealand. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- George Grey (1956). Polynesian Mythology and Ancient Traditional History of the New Zealanders, Illustrated edition, reprinted 1976. Christchurch: Whitcombe and Tombs. pp. 7–10.

- "Māori Dictionary search results for 'Haumia-tiketike'". John C Moorfield. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "Namu". Te Ara.govt. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "Whakapapa of Haumia". Te Ara.govt. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- Fletcher M.T., Hayes P.Y., Somerville M.J., De Voss J.J."Ptesculentoside, a novel norsesquiterpene glucoside from the Australian bracken fern Pteridium esculentum". Tetrahedron Letters. 51 (15) (pp 1997-1999), 2010.

- "Uses of Cordyline australis". Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Uses of Coriaria arborea - Tutu". Retrieved 3 June 2019.

Bibliography

- M. S. McGlone, J. M. Wilmshurst, and Helen M. Leach, 'An ecological and historical review of bracken (Pteridium esculentum) in New Zealand, and its cultural significance' New Zealand Journal of Ecology (2005) 29(2): 165–184.

- M. Orbell, The Concise Encyclopedia of Māori Myth and Legend (Canterbury University Press: Christchurch), 1998.