Harlem Nights

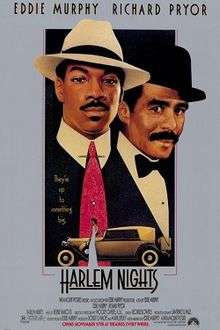

Harlem Nights is a 1989 American crime comedy-drama film written, executive produced, and directed by Eddie Murphy. Murphy co-stars with Richard Pryor as a team running a nightclub in late-1930s Harlem while contending with gangsters and corrupt police officials. The film also features Michael Lerner, Danny Aiello, Redd Foxx (in his last film before his death in 1991), Della Reese, and Murphy's brother Charlie Murphy in his first film. The film was released on November 17, 1989 by Paramount Pictures.

| Harlem Nights | |

|---|---|

Promotional poster | |

| Directed by | Eddie Murphy |

| Produced by |

|

| Written by | Eddie Murphy |

| Starring |

|

| Music by | Herbie Hancock |

| Cinematography | Woody Omens |

| Edited by |

|

Production company | Eddie Murphy Productions |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 116 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $30 million |

| Box office | $95 million[2] |

Harlem Nights remains Murphy's only directorial effort. He had always wanted to direct and star in a period piece, as well as work with Pryor, whom he considered his greatest influence in stand-up comedy.[3] Reviews of the film were generally negative, criticizing the film's slow pacing and relative lack of comedy. Nonetheless, the film was a financial success, grossing $95 million against a $30 million budget.

Plot

In Harlem, New York, 1918, Sugar Ray has a dice game. Nearly killed by an angry customer, Ray is saved by seven-year-old errand boy Vernest Brown, who shoots the man. After being told that his parents are dead, Ray decides to raise the boy as his own. And because of the boy's savvy, he is nicknamed "Quick."

Twenty years later, Ray and Quick run a nightclub called "Club Sugar Ray", with gambling and dancing in the front, and a brothel in the back that's run by Madame Vera.

Tommy Smalls, who works for the gangster Bugsy Calhoune, and Miss Dominique LaRue, Calhoune's mistress, arrive. Smalls and LaRue have come to see the club and report to Calhoune. Later, Calhoune sends corrupt detective Sgt. Phil Cantone to threaten Ray with shutting the club down unless Calhoune gets a cut.

Ray decides to shut down, but first he wants to make sure he's provided for his friends and workers. An upcoming fight between challenger Michael Kirkpatrick and defending champion (and loyal Club Sugar Ray patron) Jack Jenkins will draw much money in bets. Ray plans to place a bet on Kirkpatrick to make Calhoune think Jenkins will throw the fight. Ray also plans to rob Calhoune's booking houses. A sexy call girl named Sunshine is used to distract Calhoune's bag man Richie Vinto.

Calhoune thinks Smalls is stealing from him and has him killed. Quick is noticed near the scene by Smalls' brother Reggie who tries to kill him. Quick kills him and his men. Calhoune sends LaRue to seduce and kill Quick, but Quick realizes he is being set up and kills LaRue.

Calhoune has Club Sugar Ray burned down. Sunshine seduces Richie Vinto and tells him she has a pickup to make. Richie agrees to pick her up on the way to collect some money for Calhoune. Richie gets into an accident orchestrated by Ray's henchman Jimmy. Ray and Quick, disguised as policemen, attempt to arrest Richie, telling him that the woman he's riding around with is a drug dealer. Quick attempts to switch the bag that held Calhoune's money with the one Sunshine had placed in the car, but two white policemen "real boys" arrive. Richie explains that he's on a run for Bugsy Calhoune, so they let him go.

The championship fight begins. Two of Ray's men blow up Calhoune's "Pitty Pat Club", to retaliate against Calhoune for destroying Club Sugar Ray. At the fight, Calhoune realizes it was not fixed as he thought, and hears that his club has been destroyed. Quick and Ray arrive at a closed bank. Cantone arrives, having followed them and Ray's crew seal him inside the bank vault.

Richie arrives to deliver Calhoune's money, but tells Calhoune that the bags of money had been switched with bags of 'heroin', which turns out to be sugar. Calhoune then deduces that Ray was behind the plot. Vera visits Calhoune and tells them where to find Ray and Quick. Calhoune and his men arrive at Ray's house only to find it empty, at which point one of his men trips a bomb which kills them all. Ray and Quick pay off the two white men who disguised themselves as the policemen earlier. Ray and Quick take one last look at Harlem, knowing they can never return and that there will never be another city like it. Despite this, the two, along with Bennie and Vera, leave for an unknown location as the credits roll.

Cast

- Eddie Murphy as Vernest "Quick" Brown

- Desi Arnez Hines II as young Quick

- Richard Pryor as Sugar Ray

- Redd Foxx as Bennie Wilson

- Danny Aiello as Phil Cantone

- Michael Lerner as Bugsy Calhoune

- Della Reese as Madame Vera Walker

- Berlinda Tolbert as Annie

- Stan Shaw as Jack Jenkins

- Jasmine Guy as Dominique La Rue

- Vic Polizos as Richie Vento

- Lela Rochon as Sunshine

- David Marciano as Tony

- Arsenio Hall as Reggie

- Thomas Mikal Ford as Tommy Smalls

- Miguel A. Nunez Jr. as Man with Broken Nose

- Charlie Murphy as Jimmy

- Robin Harris as Romeo

- Uncle Ray Murphy as Willie

- Michael Buffer as Ring Announcer

- Reynaldo Rey as Gambler

- Don Familton as Referee

- Ji-Tu Cumbuka as Daryl

Production

The part of Dominique La Rue, played by Jasmine Guy, was originally cast with actress Michael Michele. Michele was fired during production because, according to Murphy, she "wasn't working out". Michele sued Murphy, saying that in reality she was fired for rejecting Murphy's romantic advances. Murphy denied the charge, saying that he had never even had a private conversation with her.[4] The lawsuit was settled out of court for an undisclosed sum.[5]

"It's turning out to be more pleasant than I expected," Pryor told Rolling Stone. "[Murphy is] wise enough to listen to people. I seen him be very patient with his actors. It's not a lark to him. He's really serious." "He's on top of the world and he's doing a hell of a job," agreed Foxx. "He sure knows how to handle people with sensitivity. He'll come over to your side and give private direction – he never embarrasses anyone." "You walk around here and look at the people," added Pryor. "Have you ever in your life seen this many black people on a movie set? I haven't."[6]

About the movie's reception, Murphy said: "That movie was a blur. It was Richard [Pryor], Robin Harris — all comedians. I remember Richard and Redd Foxx laughing offstage during the whole movie. The funniest shit was off camera, we’re all just crying. Redd was a really funny dude, he would have the set screaming all the time. But afterwards it was like, Whoa, that’s a lot of work. I was really young when I did it. I had one foot in the club, and one foot on the set, a lot of shit going on. It’s amazing it came together." He also said he didn't know Pryor was sick at the time "He was sick with MS by then, but nobody knew it was going on. And I was like a puppy to him ‘cause he was my idol. “Hey! Let’s go make this movie!” I never put it together what was happening till afterwards. So it was kind of sad, that part of it."[7]

Release

Box office

Opening in North America in mid-November 1989, the film debuted at No.1 its opening weekend.[8] It grossed $16,096,808 from 2,180 screens during those first three days setting a record pre-holiday fall opening[9] and would go on to collect a total of $60,864,870 domestically at the box office.[2] Despite a fair gross, the film was considered a box office disappointment by the studio, earning roughly half of Murphy's earlier box office successes Coming to America and Beverly Hills Cop II from the previous two years.

Critical reception

Review aggregator site Rotten Tomatoes reports a 21% score with an average score of 3.8/10 based on 34 reviews. The site's consensus states; "An all-star comedy lineup is wasted on a paper-thin plot and painfully clunky dialogue."[10] Michael Wilmington noted in the Los Angeles Times that the "production design lacks glitter. The movie also lacks the Harlem outside the gaudy gangland environs, the poverty, filth, pain, humanity, humor and danger that feeds these mobster fantasies."[11]

Movie theatre shooting controversy

On November 17, 1989, two men were shot and killed inside AMC Americana 8 theater in the Detroit suburb of Southfield, Michigan.[12] According to witnesses quoted in the Detroit Free Press, the shooting happened on opening night taking place during a shooting spree in the film's opening. A 22-year-old woman, who panicked and ran into traffic, was in critical condition two days later at the city's Providence Hospital; her name was withheld by police. Less than an hour after the shooting, police arrived at the theatre to find a 24-year-old Detroit man who had shot at an officer. The gunman was wounded when the officer shot him back in the theatre parking lot. The incident caused the theatre chain to cancel showings of Harlem Nights. One resident of the area, D'Shanna Watson, said:

There were so many people in the theater and there was so much going on, they stopped the movie three times.[13]

Later that night, brawlers were ejected from a Sacramento theater showing Harlem Nights. Their feud continued in a parking lot and ended with gunshots. Two 24-year-old men were seriously injured. An hour later, Marcel Thompson, 17, was fatally shot in a similar fight at a theater in Richmond, California. When police stopped the projection of Harlem Nights to find suspects, an hour-long riot erupted. In Boston, Mayor Raymond Flynn saw so many fistfights taking place in a crowd leaving Harlem Nights that he at first threatened to close the theater down but decided to tighten police security at the theatre. Flynn blamed the film for the riot, stating that it "glorifies violence." However, Raymond Howard, a lieutenant of the Richmond police department, defended the film, saying, "There's nothing wrong with the show. But this tells me something about the nature of kids who are going to see these shows."[14]

If there's a fight at McDonald's, what does that have to do with McDonald's? ... If there's a fight at Giants Stadium, are you going to blame the Giants? Of course not. It's not about the Eddie Murphy movie.[14]

— Bob Wachs, Eddie Murphy's manager, on the movie theatre incidents, December 4, 1989.

Accolades

- Stinkers Bad Movie Awards:

- Worst Picture

- Golden Raspberry Award:

- Worst Screenplay (Eddie Murphy)[15]

- Nominated

- Academy Awards:

- Academy Award for Best Costume Design (Joe I. Tompkins)[16]

- Golden Raspberry Award

- Worst Director (Eddie Murphy)[15]

References

- "HARLEM NIGHTS (18)". British Board of Film Classification. January 10, 1990. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- "Box Office Information for Harlem Nights". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved July 13, 2012.

- Reid, Shaheem (December 12, 2005). "Chris Rock, Bernie Mac, Eddie Murphy Call Pryor The Real King Of Comedy". MTV News. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- Zehme, Bill (August 24, 1989). "Eddie Murphy: Call Him Money". Rolling Stone. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- Kinetic Koncepts (April 7, 2017). ""New Jack City" ACTRESS Revealed Why She Filed $75M LAWSUIT Against Eddie Murphy". Old School Music. Kenner, LA.

- Zehme, Bill (August 24, 1989). "Eddie Murphy: the Rolling Stone interview". Rolling Stone: 5o.

- https://www.vulture.com/2016/12/eddie-murphy-mr-church-snl-standup.html?mid=twitter_vulture

- "WEEKEND BOX OFFICE : Murphy's 'Nights' Overtakes 'Talking'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 14, 2012.

- "'Home' finds a niche at the top; 'Rescuers' mild; 'Cyrano' solid". Variety. November 26, 1990. p. 8.

- Rotten Tomatoes, "Harlem Nights". Accessed December 17, 2014.

- "MOVIE REVIEW : Eddie Murphy's 'Harlem Nights': Slick, Slack". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 21, 2010.

- "Southfield movie theater canceled all ..." Orlando Sentinel. November 20, 1989. Retrieved July 29, 2015.

- "Shooting, violence mar 'Harlem Nights'". Ludington Daily News. November 20, 1989.

- "Violence Darkens the Bright Opening of Eddie Murphy's Plush, Flush Harlem Nights". People.com. Retrieved August 24, 2014.

- "Official summary of awards". Razzies.com. Archived from the original on July 7, 2012. Retrieved August 24, 2014.

- "The 62nd Academy Awards (1990) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Harlem Nights |

| Awards | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Caddyshack II |

Stinker Award for Worst Picture 1989 Stinkers Bad Movie Awards |

Succeeded by The Bonfire of the Vanities |