Hamont dialect

Hamont dialect or Hamont Limburgish is the city dialect and variant of Limburgish spoken in the Belgian city of Hamont (a part of Hamont-Achel) alongside the Dutch language (with which it is not mutually intelligible).[1] In the Achel part of Hamont-Achel, another dialect called Achels is spoken.

| Hamont dialect | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Belgium |

| Region | Hamont-Achel |

Indo-European

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Dorsal | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | |||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | k | ||

| voiced | b | d | ||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ʃ | x | |

| voiced | v | z | ʒ | ɣ | ɦ | |

| Trill | ʀ | |||||

| Approximant | β | l | j | |||

- /m, p, b, β/ are bilabial, whereas /f, v/ are labiodental.[1]

- The word-initial /sx/ cluster can be realized as [ɕx].[2]

- /ʃ, ʒ/ do not occur as frequently as in many other dialects, and can be said to be marginal phonemes.[2]

- /ŋ, k, x, ɣ/ are velar, whereas /j/ is palatal.[1]

- /ʀ/ is a uvular trill. Word-finally it is devoiced to either a fricative [χ] or a fricative trill [ʀ̝̊].[3]

- Other allophones include [ɱ, ɲ, c, ɡ]. They appear in contexts similar to Belgian Standard Dutch.[2]

- Voiceless consonants are regressively assimilated. An example of this is the past tense of regular verbs, where voiceless stops and fricatives are voiced before the past tense morpheme [də].[2]

- Word-final voiceless consonants are voiced in intervocalic position.[2]

Vowels

The Hamont dialect contains 22 monophthong and 13 diphthong phonemes.[4] The amount of monophthongs is higher than that of consonants.[4]

Monophthongs

| Front | Central | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| short | long | short | long | short | long | |

| Close | i | iː | y | yː | u | uː |

| Close-mid | ɪ | eː | ʏ | øː | oː | |

| Open-mid | ɛ | ɛː | œ | œː | ɔ | ɔː |

| Open | æ | æː | aː | ɑ | ɑː | |

| Unstressable | ə | |||||

On average, long vowels are 95 ms longer than short vowels. This is very similar to Belgian Standard Dutch, in which the difference is 105 ms.[2][6]

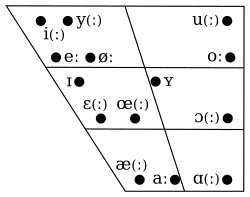

The quality of the monophthongs is as follows:

- /i, iː, u, uː, eː, oː, ɛ, ɛː, ɔ, ɔː, ɑː/ are similar to the corresponding cardinal vowels [i, u, e, o, ɛ, ɔ, ɑ], but none of them are quite as peripheral.[4]

- Among the central vowels, only /y/, /ʏ/ and /aː/ are phonetically central ([ʉ̞, ɵ, äː]), the rest of them (/yː, œ, œː/) is front [yː, œ, œː], similar to the corresponding cardinal vowels. /y/ is near-close (and slightly advanced from the central position) rather than close and /ʏ/ is close-mid. As in Standard Dutch, /ʏ/ is phonetically similar to the unstressable /ə/ and the two differ mainly in rounding. There are conflicting reports regarding the backness of /øː/ as it is depicted as front [øː] on Verhoeven's auditory chart and as central [ɵː] on the formant chart.[7]

- /ɪ/ is similar to /eː/, but it is lower and slightly more central ([ɪ̞]). For some speakers there is additional non-phonemic long [ɪː], which can appear in words such as noordenwind [ˈnoːʀdəʀβɪːnt] ('north wind'). This is probably an influence of Belgian Standard Dutch.[8]

- The contrast between the long open vowels is a genuine front–central–back contrast. The Hamont dialect thus has four, not five phonemic vowel heights.[9]

- /æː/ is open front [æ̞ː].[4]

- The short /æ/ and /ɑ/ are somewhat higher and more front ([æ, ɑ̝̈]) than their long counterparts. This is not shown on the vowel chart.[4]

Monophthong-glide combinations

All monophthong-glide combinations are restricted to the syllable coda.[10]

Diphthongs

Dialect of Hamont contrasts long and short closing diphthongs. The long ones are on average 70 ms longer than their short equivalents. Centering diphthongs are all long.[4]

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

| Closing | short | ɛi œy ɔu ɑu |

|---|---|---|

| long | ɛiː œyː ɔuː ɑuː | |

| Centering | iːə yːə uːə oːə ɔːə | |

- The starting points of /ɛi(ː), œy(ː)/ are close to the corresponding cardinal vowels [ɛ, œ].[4]

- The starting point of /ɑu(ː)/ is near-open central [ɐ].[4]

- The ending points of /ɛi(ː), œy(ː), ɔu(ː)/ are rather close, more like [i, y, u] than [ɪ, ʏ, ʊ].[4]

- The ending point of /ɑu(ː)/ is slightly more open ([ʊ]) than those of the other closing diphthongs.[4]

- The starting points of /ɔu(ː)/ and /oːə/ are more central than the corresponding cardinal vowels: [ɔ̟, o̟].[4]

- The starting points of /iːə, yːə/ are somewhat lower ([i̞, y˕]) than the corresponding cardinal vowels.[4]

- The starting point of /uːə/ is somewhat lower and somewhat more central ([ü̞]) than the corresponding cardinal vowel.[4]

- The starting point of /ɔːə/ is somewhat higher and somewhat more central ([ɔ̝̈]) than the corresponding cardinal vowel.[4]

Prosody

Like most other Limburgish dialects, but unlike some other dialects in this area,[11][12] the prosody of the Hamont dialect has a lexical tone distinction, which is traditionally referred to as stoottoon ('push tone') or Accent 1 and sleeptoon ('dragging tone') or Accent 2. They are transcribed as superscript 1 and superscript 2, respectively. This distinction can signal either lexical differences or grammatical distinctions, such as those between the singular and the plural forms of some nouns.[13]

| Accent 1 | Accent 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| IPA | Meaning | IPA | Meaning |

| /ɦus¹/ | '(record) sleeve' | /ɦus²/ | 'house' |

| /kəˈnin¹/ | 'rabbits' | /kəˈniːn²/ | 'rabbit' |

| /tiːən¹/ | 'toes' | /tiːən²/ | 'toe' |

The distinction between Accent 1 and Accent 2 is phonemic only in stressed syllables.[13]

In final position, Accent 1 is realised as a steady fall [V˥˩] through the rhyme, the Accent 2 is falling-rising [V˥˩˩˥]; the first half of the rhyme is falling, whereas the rest is rising.[13]

In non-final position, Accent 1's F0 stays high in the first 45% of the rhyme and then falls rapidly towards the end of the rhyme (in IPA, that can be transcribed [V˦˥]). When the focus of the sentence is on a word with Accent 2, it is realized as a very shallow fall-rise combination [V˥˩˩˥].[14]

Vowels with Accent 1 are generally shorter than those with Accent 2.[14]

Sample

The sample text is a reading of the first sentence of The North Wind and the Sun, read by a 75-year-old male middle-class speaker.[1]

Phonetic transcription

[də noːʀdəʀβ̞ɪːnd ɛn də zɔn | di β̞ɑʀə ʀyzi n̩t maːkə ʔoːvəʀ β̞i t̩ stɛʀkstə β̞ɑs | tun əʀənə vɛ̃ːnt fəʀbɛiː kβ̞ɑːmp mɛ nə β̞ɛʀmə jɑz ɔːn][15]

Orthographic version (Standard Belgian Dutch)

De noordenwind en de zon waren ruzie aan het maken over wie het sterkste was toen er een man voorbij kwam met een warme jas aan.[16]

References

- Verhoeven (2007), p. 219.

- Verhoeven (2007), p. 220.

- Verhoeven (2007), pp. 220–221.

- Verhoeven (2007), p. 221.

- Verhoeven (2007), pp. 220–222.

- Verhoeven & Van Bael (2002).

- Verhoeven (2007), pp. 220–221, 223.

- Verhoeven (2007), pp. 221, 224.

- Verhoeven (2007), pp. 221–222.

- Verhoeven (2007), p. 222.

- Schouten & Peeters (1996).

- Heijmans & Gussenhoven (1998), p. 111.

- Verhoeven (2007), p. 223.

- Verhoeven (2007), p. 224.

- Verhoeven (2007:224–225). Note that the author transcribes de as *[de], rather than the correct [də].

- Verhoeven (2007), p. 225.

Bibliography

- Heijmans, Linda; Gussenhoven, Carlos (1998), "The Dutch dialect of Weert" (PDF), Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 28: 107–112, doi:10.1017/S0025100300006307

- Schouten, Bert; Peeters, Wim (1996), "The Middle High German vowel shift, measured acoustically in Dutch and Belgian Limburg: diphthongization of short vowels.", Zeitschrift für Dialektologie und Linguistik, 63: 30–48, JSTOR 40504077

- Verhoeven, Jo; Van Bael, Christophe (2002), "Akoestische kenmerken van de Nederlandse klinkers in drie Vlaamse regio's" (PDF), Taal en Tongval, 54: 1–23

- Verhoeven, Jo (2007), "The Belgian Limburg dialect of Hamont", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 37 (2): 219–225, doi:10.1017/S0025100307002940